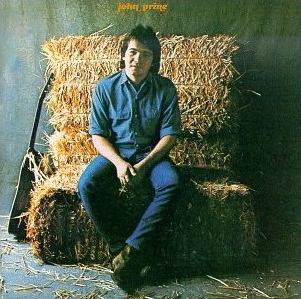

On the April night when John Prine died, my father and I stayed up until 2:30 a.m. I was quarantining in my parents’ apartment in Massachusetts, a thousand miles from my home in Nashville. Eleanor and I had come up for a week in early March, and a week had turned into a month, then a month into the borderless present. It was still early days, but even then the concepts of early and late had begun to blur around the edges, like words in a language we were all starting to unlearn.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in