At this point it’s obvious that Americanness in the twenty-first century is less about work ethic, grand imagination, or high achievement than it is about continually contenting ourselves with silver linings to ever-darkening clouds. Most dreams of the past have either evaporated or been reduced to damp muck on the floor of what was once thought, apparently, to be an ocean of possibility.

It’s clear now why we won’t beat the coronavirus, as other nations are proving able to do: we’re incapable of both short-term sacrifice and conceiving of freedom as more than the gratification of our immediate individual desires. There’s even a sense of relief that pandemic is distracting us from the other issues we’re incapable of addressing—ecological collapse, housing crises, regular mass shootings—whose circular discussion was getting tiresome. A sense of finally settling on mass death as not just a fact but the defining feature of our nation’s existence. That there are no broad collective victories to be had, just concessions to make and to be grateful for.

Having unexpectedly wound up for some months in my hometown of Roanoke, Virginia, I was grateful for the time with family I don’t often see. Like others, perhaps, I tried to envisage unemployment as a sort of vacation. With new time on my hands, I started working on a project that had been kicking around in my head for a couple of years. A silver lining whose faint glow becomes a primary source of light.

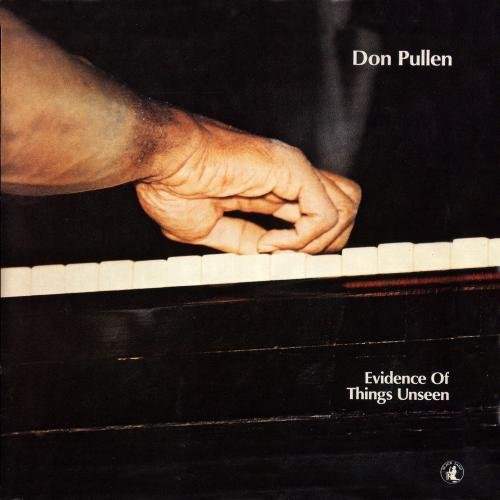

My project is to help Roanoke create a public memorial to acknowledge its greatest musician, the jazz pianist Don Pullen. Perhaps “project” isn’t yet the word for what has so far consisted of some library inquiries, a lot of reading and listening, and a series of conversations with the family, friends, and colleagues of Pullen, who died of lymphoma in 1995. During a summer marked by seclusion and anti-racist uprising, it seems, there’s not much to be done except research. Sowing seeds, gauging interest.

In relating the project’s aims I find myself repeating the same litany: Pullen played with hugely influential avant-gardists Giuseppe Logan and Milford Graves in the 1960s, joined Charles Mingus in the mid-’70s, left Mingus with his bandmates to start their own quartet, led some other prolific bands of his own, and recorded a number of solo piano albums that I adore. Heathen that I am, I learn that a favorite from this last category, Evidence of Things Unseen, draws its name not from James Baldwin’s book-length essay about the Atlanta murders of 1979–1981, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, but from Hebrews 11:1: “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”

My (older) brother, not a heathen but a scholar of theology, tells me this verse is often invoked by bad-faith Christians who want to emphasize the immaterial expectations of contemporary Christianity now that it’s shifted from the religion of poor people, women, and slaves to the religion of the state. Recognizing faith as substance enough, a nation can justify all manner of atrocities: as long as the perpetrators have Jesus in their hearts, absolution and salvation are theirs regardless of their deleterious effects on worldly affairs. “It’s a verse that gets used when people are trying to move your attention to something non-physical,” he says.

My (twin) brother and I get to know Pullen’s son Keith, who is devout and deeply involved at his church. He’s working on a book about his father, and after hearing about our wish to create a Don Pullen memorial he tells us he thinks God has brought the project to him at a perfect time. When we ask if he knew much about his father’s religious beliefs, Keith says he isn’t sure of the details, but knows his dad was a spiritual person and thinks you can feel it in his music. My brother and I agree.

Evidence of Things Unseen is in many ways an exemplary Don Pullen recording. He’s a pianist known for veering into extreme atonality while keeping a strong harmonic structure at the center of his playing. On “Victory Dance (For Sharon),” his famously wild right hand dashes around the keyboard, releasing blasts of incomprehensible dissonance, while his left preserves a beautiful established motif. It’s like a duet between Joe Bonner and Cecil Taylor. The title piece overlays a similar strategy onto a devastating ballad. As Stanley Crouch describes it, “what begins with a singing tenderness and delicacy will mount in to exuberant flurries as the voicings become more and more dense, then the graceful, almost soothing, relaxation will smooth away the agitation and resolve it all, something like the embrace a fighter will give his wife after a battle in which all that mattered was speed, power, and rhythm.”

Now home in New York, I hear the record and feel simultaneously closer to and more distant from Roanoke. These months have made me grateful to have grown up there but glad to have moved away. Pullen’s life and music reassure me that a small city can produce true radicals, but that they need to go elsewhere to realize their potential. Research has not yet produced any authoritative accounts of his relationship to the city, but perhaps his life tells the story: he left to attend Johnson C. Smith College in Charlotte at seventeen and never lived there again. As I listen it occurs to me that to be radical is to believe that faith is not a substance, and that the goal of hope has to be concrete, clearly visible. I’ll sit inside but continue to look for it.

— Brandon Wilner

Roanoke, VA and New York City, day 170