In my Las Vegas kitchen, I sing “Say It Isn’t So” into a plastic whisk. I’ve logged hundreds, maybe thousands, of karaoke hours in my lifetime, but had never sung this song before last month. Nights at Duet 35 in K-Town, in a room full of friends, I usually left the Hall & Oates, the “Sara Smile,” to more versatile singers. Now I sing “Say It Isn’t So” several times a week, cranking the volume on YouTube. The video starts with feet walking in time with the bassline, a determined synth creep of big harmony and pop longing. Hall appears in a striped scarf and a sweep of blond hair, Oates in his dark mustache and leather jacket, and there’s a mouthful of sadness behind the keyboard sparkle, the chords not major enough to pass for unabashedly upbeat. It’s a song about delusion, brightness juxtaposed against its heartbreak lyrics—the singer refuses to believe it’s over, Baby say it isn’t so!—and I sing it through my own delusions and magical thinking: that there will be a next year and a year after, that I’ll be able to see and hug my family again, that there will be a when all this is over and we will all somehow be okay, though already we aren’t.

Twenty years ago, I first rediscovered “Say It Isn’t So” on a Napster binge at my office job, where I did data entry while chatting with friends on AIM. Suddenly there was free—pirated—access to forgotten songs, little thrill hits of nostalgia in my windowless cubicle, curiosities dug from the crates of my mind. Would they sound as good as I remembered? Back then it was a tiny shock of delight to download an MP3, open Winamp, and hit play. Now hearing the song triggers a deep, cellular nostalgia, like the night I heard my neighbors in Brooklyn drunk-belting Julio Iglesias’s “Me olvidé de vivir” out their open windows, and remembered my dad and his friends, blotto and maudlin at parties, doing the same: a stereoscope of lost times and places. Rehearing “Say It Isn’t So,” remembering rehearing it twenty years ago, remembering first listening to it thirty-five years ago, a memory of a memory of a memory, feels like running into a friend from another lifetime. They’ve aged so much, and you have, too, but once you start talking you can almost pretend you both haven’t.

I’m nearing the end of a semester-long writing fellowship in Las Vegas, a city I had fun getting to know before it shrank down to my apartment and a five-block radius. Beyond that are the closed casinos, restaurants, and hotels. The first week of March, Julman flew out from New York for a ten-day visit, but when city schools closed and his office shut down we decided he should stay, both of us now working remotely, indefinitely, in one room. Back in New York, outside our Flatbush apartment, hundreds of people are dying every day, and we don’t know when and how we’ll be able to get home. The rage, fear, and grief feel bottomless. I talk on the phone for hours and mail letters to friends, just like I did in middle school. I eat Doritos, Pringles, pan de sal, and other comfort foods. We attempt to juggle our impossible jobs with caring for our families across the country, finally putting together our wills, horrified and outraged, worrying about fascism, about our elderly parents and paying rent, listening to stories of hospital stays, test denials, employers not giving out masks, and refrigerated trucks, and I grieve a vision of a future I know I will never have, one that was never promised to begin with. In my forties, without kids, I feel like I’m in a boat that only recently found balance and is now about to be plunged over a waterfall. At night we join Zoom dance parties, watch ’80s movies we vaguely remember seeing on TV or VHS, listen to D-Nice spin his Gen-X retro music joy, and attach ourselves to the internet like we haven’t since Web 1.0. On video chats, when our friends’ voices are drowned out by sirens driving past their Bronx and Queens apartments, we tear up unexpectedly, our breath catches. We karaoke through our screens, with friends and sometimes without, using the whisk, a wooden spoon, a plastic stove lighter as a mic.

Hall & Oates arrive from the same hazy past as snail mail and marathon phone calls, familiar sincerity remixed into an anxious, ominous present. Here in Las Vegas, in a home that is also not home, the only places I’ve gone in the past two months are the vast, empty parking lot where we pace five thousand steps a day at sunset and the silent blocks of closed attorney offices and wedding chapels where we walk to the distant sounds of sprinklers or ambulances and the occasional exhale of an empty bus. On weekends, caravans of trucks drive up Las Vegas Boulevard, honking and waving MAGA flags. I watch at the window and ask Julman to turn up the music. There are mountains visible from all directions, sharp and stunning against a pink and lavender sky, but we can’t get there. Every day is sunny, 100 degrees by late April.

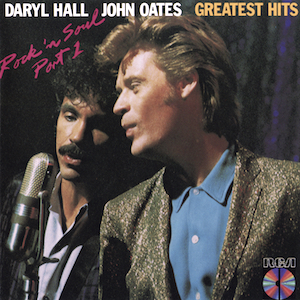

“Say It Isn’t So” came out as a single in October 1983 with “Kiss on My List” as the B-side. It was one of two new tracks on Rock ’n Soul Part 1, Hall & Oates’s compilation album stuffed with #1 hits, a cooler, less obvious choice than “Maneater” or “Private Eyes.” The first verse goes easy, right into the second, no chorus payoff yet. I’m singing along—I know your first reaction / You sliiide away / Hide away, goodbye—and I am nine years old in the summer of 1985, unable to see my friends because I can’t get anywhere on my own, living inside MTV every day. The heat has baked the pavement outside and I’m stranded in a New Jersey basement, an only child watching TV alone on a scratchy sofa with an orange and brown fruit print that smells like delicious mildew, eating Doritos and Otter Pops, drinking paper cups of Kool-Aid and Tang. On MTV, Hall & Oates are in heavy rotation. They seem older than other pop stars; Daryl Hall is only a year younger than my mom. Their appeal is catchy, a little corny, a PG-13 kind of love.

The ramp-up to the chorus of “Say It Isn’t So” is an achy ladder of major-seventh chords, delayed gratification that busts out into a major-chord plea. In the video, the band plays in a dark New York City lot until Hall kicks a door open and releases us into sudden sunshine, and now they’re strumming their guitars on a pier overlooking the Hudson River and Jersey skyline, hair and scarves soft in the breeze. Charlie DeChant, the saxophonist, plays his solo in a fur coat. Tom Wolk, the bassist, said that Oates’s background vocals—say it isn’t so, oh oh oh—were inspired by the Flamingos’ “I Only Have Eyes for You”: an ’80s synth refraction of a woozy ’50s doo-wop love song. And here’s that ’80s refraction refracted in the first months of the ’20s, in a year with no discernible future.

So, okay. Despair, but make it sunny. Listen to the payoff in the refrain! Hear it build then fly, that brightness, that brief minor dip, the way the words tighten and duck in and out of the beat, a yearning eternally trapped somewhere between denial and acceptance. The band keeps playing as the camera pulls back above the water, and I’m singing into a whisk in my kitchen at one in the morning like I sang into it at one in the morning a few nights ago. Through my window I can see the street sweepers drive back and forth, focused and beeping, lighting up an otherwise empty night.

—Lisa Ko

Las Vegas, day 47