In the cold early morning hours of the second day of 2018, I took myself to the doctor. I had not been able to sleep all night for coughing. I felt breathless, as though I couldn’t get enough air in. I explained this to the doctor at CitiMD. I had hoped he would give me something to help me breathe. Instead, he asked if there had been anything else wrong lately. I explained that I had been tired, light-headed, and prone to feeling very cold. I could never get warm. I had been fainting.

He stopped me at “fainting.” How many times had I fainted? The answer was, perhaps five times, in a six-week period.

The doctor looked at me like I was mad. “It didn’t occur to you to come to a doctor when you fainted the first time?”

I told him it had not.

“There’s no reason why a young lady such as yourself should be fainting and feeling dizzy all the time,” he said.

Then the tests commenced. I took off my cardigan and my shirt, and sensors were placed on my chest so that the nurse could perform an EKG. When the doctor came back into the exam room he looked concerned. The EKG had detected some abnormalities.

He told me to go to the ER immediately. He asked whether he should order me an ambulance, or whether he could trust me to take myself there on my own.

I told him that he could, but that I didn’t understand what has going on. I asked whether a hospital was really necessary.

“They can do blood work and X-rays more quickly there than I can here,” the doctor explained. “Hopefully everything is fine. If they find something they’ll refer you to a cardiologist or a neurologist, to try and find out what’s happening between your head and your heart.” As he spoke he placed one hand to the side of his head, and one on his heart, as though to embody the metaphor of my own disequilibrium.

I spent the next eight hours in the Emergency Room of Mount Sinai Beth Israel on 3rd Avenue. I had been sent to that pale orange Emergency Room before, a year and a half earlier. On that occasion I had pulled a muscle in my back and suffered spasms so excruciating I couldn’t walk. My husband called 911. The paramedics carried me down the three floors of the apartment building strapped into a chair, still barefoot and wearing a nightie, and took me in an ambulance to the hospital so that I could be administered with a heavy dose of muscle relaxants and Percocet. When the paramedics had wheeled me into the emergency room that last time, a nurse had attached a yellow bracelet to my wrist. It read “Fall Risk.”

Now I was back in the Emergency Room at Mount Sinai Beth Israel, a “Fall Risk” again. Tests were performed. My blood was taken. An X-ray was done. I was given two further EKGs. Between tests I lay on a bed separated from the bed on the other side by a blue curtain. My husband brought me a muffin and a bottle of water. We sat there together reading our books and waiting for the diagnosis. I put a hand on my heart, every so often, to check that it was beating correctly. It seemed okay to me.

And, in fact, it was. When the doctor on call at last came to talk to me, she explained that the abnormalities in the electrical function of my heart were certainly present in the tests they had administered, but didn’t seem worrisome. “Abnormalities aren’t always abnormalities, that’s to say, they might be entirely normal for you,” she said. They couldn’t determine why I had been feeling faint or light-headed after all the tests, but she advised that I rest, drink water, try to extricate myself from any stressful situations which might have been causing me distress. When I was given my discharge papers, I looked at the official diagnosis the hospital had given me. It read “Weakness, with no known cause.”

The fainting had begun in November. It happened for the first time on a warm afternoon in downtown Phoenix, in a bookstore, on the Friday after Thanksgiving. First, my peripheral vision closed in. Next, things went quiet, as though the volume knob had been turned down on the world. Finally, a swooping sensation that started at the back of my skull and located itself just as squarely in my throat. The swooping produced a feeling of dispersal, and darkness. It was very much as though somebody had walked through the rooms of my self, gradually turning out the lights. I fell, and came to after a few moments by the books on the bottom shelf.

Sunstroke, I thought on the floor. My husband and I had been on a hike with his parents to the top of Piestewa Peak earlier that day. I probably should have worn a hat. I should have drunk more water. My husband helped me up from the floor and out of the bookstore where the shimmery weirdness of the city was resolving into dusk as we walked down wide streets framed by mountains towards the car. We drove back to his parents’ house down freeways bordered by saguaro, all of it taking on a gauzy quality in my newly-loose perception of the world. Back at the house my father-in-law, a rheumatologist, brought out a blood pressure monitor from a cupboard and strapped it to my arm while I sat at the dining table. My blood pressure is always low, but that afternoon I had hypotension. Probably sunstroke, nodded my father-in-law. I wandered outside and fell asleep on garden furniture by the swimming pool. When I woke up the stars were out. The night was chilly, but nothing so cold as the coldness that had descended on the east coast.

By the time the fainting started there were any number of worrying situations that might have been causing me distress, revolving in constellation around me. Winter had begun, which I’ve never, since moving from the snowless climate of Sydney, dealt with well. I had finished graduate school at Columbia six months earlier. I had completed a novel, and was waiting to find out what would become of it. My father and I had recently stopped speaking. I often had nightmares in the middle of the night.

Most of the time, I was alone in our Brooklyn apartment, working while my husband went back to Phoenix for days or weeks at a time, to be with his mother who was dying from pancreatic cancer. An old friend was diagnosed with leukemia, another stopped speaking to me, many others moved away. Holiday parties that year felt quieter than normal, pointedly well-lit, the atmosphere one of rage and grief. We were at an impasse, my friend Cam observed outside a bar one night. He described this period as “a space of time lived without narrative genre.”

What underlay everything else was the limbo created by the American immigration system. My husband and I were approaching the date set for our green card interview. We had been waiting to be interviewed for over a year, since we had married at the beginning of 2017, a time during which I had a tenuous and undefined residency status. I longed for stability, to sense that the ground was firm beneath my feet. In this period of waiting I was beset by the anxiety that something would go wrong, some policy would change, some calamity befall us, and I wouldn’t be able to stay.

There were, in short, many worrying situations mingling together at once, but it did not occur to me that I was upset about any of them. What I was, was dizzy. What I was, was tired. It took me some time to see that the issue might be the relationship between what was going on between my head and my heart.

During university I enrolled in a course called ‘Metaphor and Meaning.’ The class explored how the human brain understands metaphor by examining various theories of comprehension. The theory I was most taken with was Conceptual Metaphor Theory. “Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature,” wrote George Lakoff and Mark Turner in Metaphors We Live By, the fundamental text which first outlined the theory in 1980. Conceptual metaphor theory works on the principal of “embodied cognition.” In other words, the metaphors we use most commonly are rooted in the ways our bodies experience the world. We use physiological terms to describe abstract concepts: argument as war, love as a journey. Our bodies are the containers for our thoughts, the theory suggests, and our metaphors originate in our bodies. Physicality precedes articulation.

Conceptual Metaphor Theory is a flawed concept—for one thing, it has difficulty accounting for the ways in which our cultures, not just our bodies, impact our understanding of metaphor. But even though I could see the problems with the theory, I loved it. It suggested to me some essential truth about the way we use language, and how we create meaning. I received a Distinction for the paper I wrote for that class, although my professor wrote me a note explaining that he thought I was letting my partiality for the theory cloud my capacity for reason.

I bring this up because it seemed to me then, and seems to me now, that my tendency to faint and fall that winter was a product of embodied cognition. I was weak with no known cause. Something was going on between my head and my heart.

Fainting is feminine, annoyingly so. Medically known as syncope, fainting is the body shutting down, the fight or flight response gone awry. The triggers are frequently emotional, but they are sometimes due to pain, or prolonged standing, or crowded rooms. But in cultural representations of fainting, it’s generally emotional trouble that causes fainting, and it’s typically engaged in by women.

When women are depicted in the act of fainting, they are often represented as swooning, and swooning is always psychogenic. Its gestural economy is one of weakness, surrender, an inability to cope. The most common image of fainting in art history is of Mary falling at the foot of the Cross. In paintings like Rembrandt’s ‘Descent from the Cross’ Mary’s posture and paleness symbolizes not only emotional agony, but echoes the suffering of Christ. Fainting is hard to miss, the opposite of discrete, and reeks of melodrama. The great eighteenth century novel Clarissa is full of faints and swoons, a habit we are made to understand demonstrates the heroine’s sensitivity as she is drugged and raped, which leads, naturally, to her inevitable decline. The descriptions of women fainting and swooning in eighteenth century literature popularized the idea that women, who wore corsets and were discouraged from eating in public, were liable to fall when they were emotional. Indeed, the melodramas of early cinema and stage were full of women who swooned. Unlike fainting, swooning in literature and film is never just medical, it always signifies something about the character swooning. It’s often the return of something repressed, or the product of too much feeling. It both reinforces stereotypes around femininity, regardless of gender, and is used to suggest the failure of language to express the extremes of emotion.

When I was in London recently I visited Freud’s house in Hampstead. I had seen photographs of his office before, but I had not known about the lithograph hanging over infamous psychoanalytic couch. The lithograph in Freud’s London office is a reproduction of Andre Brouillet’s 1887 painting “A Clinical Lesson at the Salpetriere.” When I was in university, I printed out a copy of the same painting and taped it beside my desk.

Brouillet’s painting depicts a demonstration of hypnosis performed by the renowned doctor Charcot. The woman pictured in the painting was known as Blanche, and she was the frequent star patient at Charcot’s weekly demonstrations in Paris. In the painting, Blanche is partially undressed, her shoulders revealed. She has fallen, and is being held by one of the doctors standing behind her. Her face is expressionless and lovely. It looks like a lovers’ swoon, except it is not. Blanche is a hysteric, and Charcot is demonstrating a hypnotically induced lethargy. Twenty-seven male observers look on. The painting was a great success when it was exhibited at the 1887 Paris Salon, and just like the twenty-seven men depicted in the painting, the audience could enjoy the spectacle of the semi-naked falling woman, and admire the power of medical science. Freud kept the lithograph of the painting hanging in his office, a reminder of his days as a doctor at the Salpetriere Hospital in Paris, the place where psychoanalysis had first begun to take form in his mind.

Swooning and fainting were acts frequently performed by hysterics at the Salpetriere, and indeed Freud’s study of hysteria led to the popularization of the idea that unconscious conflict might be transformed into bodily complaint. Exhibitions like those depicted in Brouillet’s painting were open to the public and occurred weekly. Everybody saw them. Some of the hysterical patients were the greatest theatrical stars of their era. Doctors at the Salpetriere believed they had systematised the symptoms of the hysterical patient, so much so that they even published a kind of alphabet of gesture. Hysterical patients, nearly always women, could be read. And they needed reading, not because they were incapable of communicating, but because their bodies communicated so much more.

The women frequently engaged in fits of fainting during Charcot’s demonstrations. These hysterical faints found their way onto the stage. Sarah Bernhardt, the most widely respected actress of her era, attended the demonstrations at the Salpetriere. She learned to mimic the patients, and while she was preparing for her role in the Eugene Scribe play, Adrienne Lecouvreur, she spent time locked in one of the Salpetriere’s cells to prepare for the her role. Sarah Bernhardt is frequently who we are thinking of when we imagine swooning. Archived images of her performance catch her clutching her limbs, extending her arms, falling into chairs, onto the floor, or into the waiting arms of a strong man. She is a woman who can barely keep herself upright, someone being pulled forever towards the ground. Melodramas like Bernhardt’s became the stuff of parody. Now, an emotional faint is a melodramatic faint. Moreover, it suggests a particularly feminine pathology.

Hysteria was done away with as a diagnostic condition early in the twentieth century, and its symptoms, which cannot be explained by a known neurological disease, were re-categorized under a new diagnosis, conversion disorder. I do not mean to suggest that I was hysterical in the winter of 2017-18. I was not. I am a mostly rational woman who has never been seriously ill. I studied and wrote about hysteria in university, and I have always found hysteria useful as a prism through which to see people’s behavior, because it demonstrates if nothing else that the body sometimes articulates things that the mind cannot. During those moments after I found myself lying on the floor, the image that was always in my head was that of Blanche depicted in Brouillet’s painting. The fainting was amusing, I thought, because it suggested melodrama, something overly-emotional. But then, what, I would ask myself, am I embodying when I faint? Was I really ill?

If you feel like you’re going to faint, you’re told to put your head between your knees. This is to increase blood flow to your head. There is, in other words, a disconnect between your head and your heart, as the doctor on call at CitiMD pantomimed for me in the examination room.

After Thanksgiving the fainting took on a kind of regularity. It always followed the same pattern. The prodrome consisted of light-headedness, graying vision, the sensation of distance, the volume turned down. Often, it could all be averted by sitting down, hanging onto things, and sometimes by lying prone on the floor. If I didn’t avert it, the actual period of unconsciousness lasted for perhaps thirty seconds, maybe a minute. I would wake up pale, cold, and exhausted. Christmas was approaching, and the bookstore in SoHo where I work was busier each day. Shelving came to present an occupational hazard. I crouched low to shelve Rachel Cusk, then stood up high to shelve Dickens, and would find my vision beginning to blacken. One morning I fainted in the corner between British and Nordic literature while I was alphabetizing Samuel Beckett novels. I slumped against the wall, but nobody noticed, and after I came to and collected the books I’d spilled I told nobody. Instead I make lifestyle changes. I drank a lot of water. I cut down on alcohol. I took the iron supplements I’d meant to take since I stopped eating meat four years ago, and I cooked vats of beans and lentils in the hope that they would make me feel stronger. A friend who is vegan recommended a liquid iron drink, which he said was cheaper in Canada. I bought it, at American retail price. I did everything I could think of to make myself feel less groundless and breakable, bar going to a doctor.

On a Friday night shortly after I’d again become a Fall Risk, I finished work and went to a bar with some friends. When we left I was drunk, and decided to walk the long way to the L train. I headed north up Lafayette Street, and along Astor Place. When you emerge from Astor Place onto Broadway and look across the street, the 35-story building in front of you, the tallest thing in sight, is 300 Mercer Street. On the street level a diner sits next to a liquor store, which sits next to a salad bar on the corner of Waverley Place. It was on the roof of the salad bar, which was once Delion’s Deli, that the body of the artist Ana Mendieta was found in the early hours of September 8, 1985. That night in January, I stood on the corner outside a Vitamin Shoppe and looked up. I looked up for a long time, at the second highest story of the building, contemplating the sheer distance of the fall. And then I left.

In the next few weeks, I found myself walking up Broadway when I’d finished work, back to where Waverley and Astor Place meet. I continued circling back to the corner where Ana Mendieta died, because there was something hypnotizing about seeing the great height from which she’d fallen. I suspected that my fascination with the fall was trying to instruct me in something I couldn’t yet name or comprehend.

Mendieta’s body had been found naked but for her underpants on the roof of the deli. A doorman of a nearby building reported that he had heard a woman’s voice shouting, “No, no, no,” and “don’t” before hearing the explosive sound of her body hitting the deli’s roof. Her husband, the sculptor Carl Andre, was charged with pushing her to her death from the window of his apartment on the second highest floor of 300 Mercer Street. Four days after her death, Andre wrote a letter to Mendieta’s sister. It read, “Ana fell & I am falling still.”

Mendieta was less than five feet tall. The windowsill in the bedroom came up to her chest. If she had accidentally fallen out the window of 300 Mercer Street, she’d have had to have fallen up three feet, and then thrust herself across the radiator cover, the windowsill and the ledge, before gravity took over. And if she jumped? People who knew of Mendieta’s fear of heights said she couldn’t possibly have jumped on purpose.

When Andre was acquitted it was, the judge concluded, because ”the defendant’s guilt was not proven beyond a reasonable doubt.” The New York Times reported that, “Mr. Andre, his hands buried deep in the pockets of his spotless blue overalls, stood silently and received the verdict without any sign of emotion.” Whether she was pushed or jumped was never determined. The one solid fact about Mendieta’s death was the fall. Thirty-five stories in 4.21 seconds.

When Mendieta’s body was found on the roof of the building which is now a salad bar I have never had the stomach to enter, the impact of the fall had dented the roof. Later a physicist would calculate that at the moment of impact, her velocity was 120-miles-per-hour. Nearly everything in her body was destroyed. Her heart was the only organ that remained structurally normal. It weighed 250 grams.

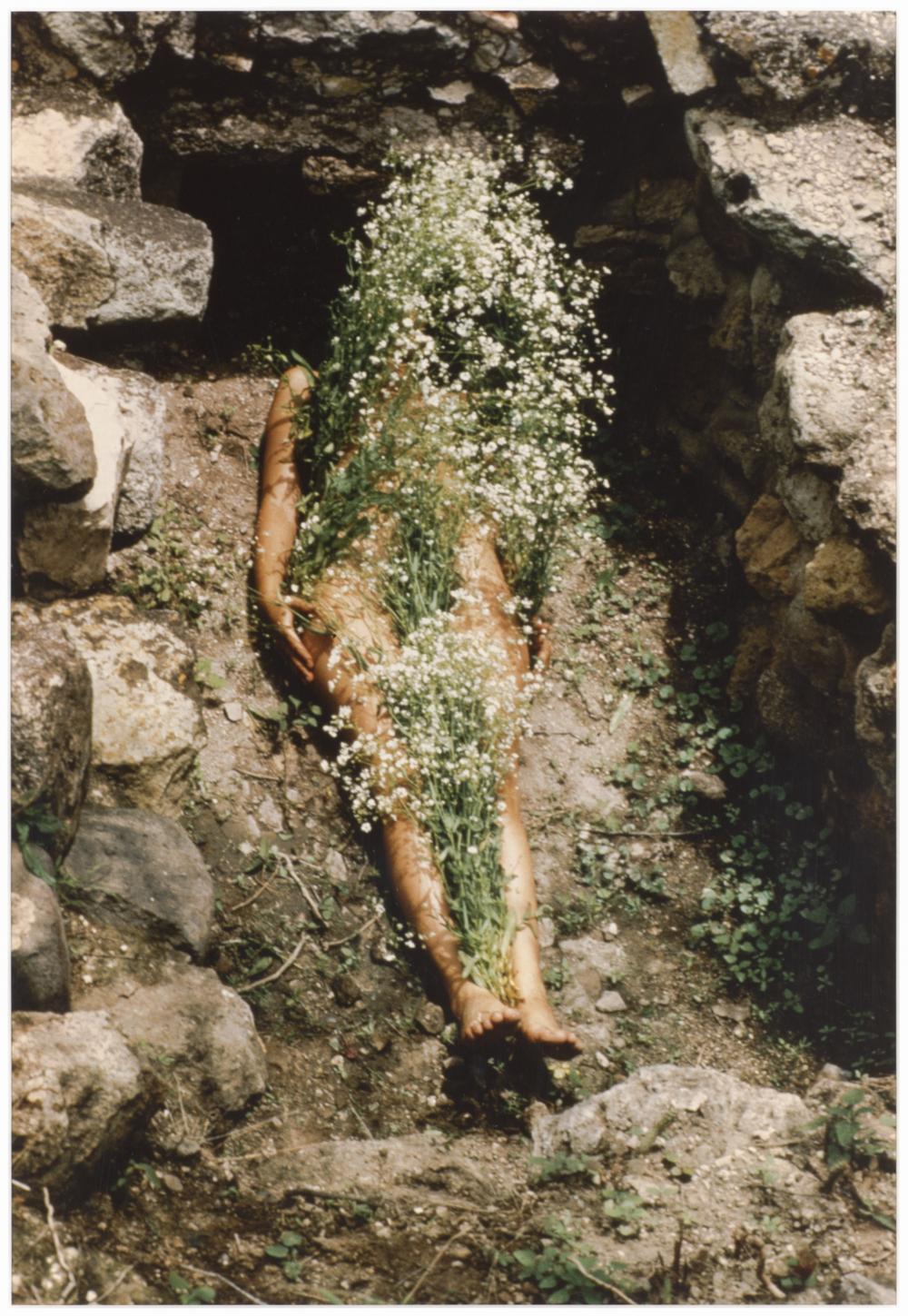

The first image I saw of Ana Mendieta was a photograph still from a piece she made in Mexico, lying naked in a deep field of grass, with flowers seeming to grow straight out of her flesh. The image was on the front cover of a monograph on display at the bookstore where I work. I sat the book aside for myself and bought it once I got paid. I had not heard of Mendieta before, although I had heard of Carl Andre. When we were first dating, my husband had been interested in conceptual art. We had, during the summer of 2014, taken the train to a gallery two hours north of the city where this kind of art is on display. Down in a basement, my husband had pointed to an installation piece and said, “Jesus Christ. More Carl Andre.” He told me Andre had been charged with murdering his wife. It had not occurred to me to ask who Andre’s wife was.

When Andre was on trial for the murder of Mendieta, his defense team cited the works that most fascinated me. When questioning witnesses, the defense team asked, among other things, whether they were familiar with Mendieta’s interest in Santería, the use of blood in her works, and whether they had seen Mendieta’s works which used her own body “impacting on the earth.” These included pieces in which she had had a firework-maker in Oaxaca make a firework piece in the shape of the outline of her body, and waited until night to set it alight. It included works where she lay naked in the open tombs of ancient Zapotec sites. In which she had covered her body with a white sheet, and had an ex-boyfriend pour pig’s blood over her shape until she was entirely soaked. The clear indication, they seemed to be suggesting, was that her death—a fall from a great height—was a work of art.

In the months before I began to faint, I noticed that my mind was often reaching for metaphors of groundlessness to describe the turn of events in my life. I was reaching for Blanche, for Sarah Bernhardt, for Ana Mendieta. In texts and emails I spoke of needing to feel “grounded.” I started going to yoga in an effort to stop the dizziness. At the end of classes when we lay on the floor, the instructor would advise us to press our bodies into the ground. “Impacting on the earth,” I would repeat to myself in my head. I had been reading Robert Katz’s now out-of-print book about Andre’s trial for Mendieta’s death. I commented to a friend that this five-minute period in yoga when I felt my body “impacting on the earth” was the entire reason I was going to yoga classes. I knew where the phrase came from.

The artist and essayist Hito Steyerl writes that the experience of living in the world today “is distinguished by a prevailing condition of groundlessness.” In a 2011 essay for e-Flux entitled ‘In Free Fall,’ she argues that “we cannot assume any stable ground on which to base metaphysical claims or foundational political myths. At best, we are faced with temporary, contingent, and partial attempts at grounding,” she writes, observing that “the consequence must be a permanent, or at least intermittent state of free fall for subjects and objects alike.” Steyerl’s interest in her essay is in the way that falling creates a shift in perspective. She points to the stories that pilots sometimes tell, about having been in planes during free fall, when the sudden descent can create a blurring between the boundaries of self and plane. This kind of blurring of perspective produces what she calls “a new representational freedom.” To assume that we need to be grounded in the first place may very well be a kind of false cognition, the kind of conservative thinking favored by traditionalists. “Falling means ruin and demise as well as love and abandon, passion and surrender, decline and catastrophe,” she concludes. “Falling… takes place in an opening we could endure or enjoy, embrace or suffer, or simply accept as reality.”

Steyerl’s essay, published in 2011, contains all the optimism of the year that saw both the Arab Spring and the birth of Occupy. It was a year everything suddenly seemed like it was open to change, like the ground had fallen out but what was to come would be if not good, then at least interesting. But at the end of 2017 the groundlessness Steyerl proposed as a new possibility for experiencing freedom seemed to me only awful and anxiety-inducing. I longed for the certainty of the ground now that the bottom had fallen out of things. Nothing in politics, nor the environment, nor in my social sphere, felt grounded any longer. A feeling of falling seemed like a perfectly legitimate response to the world, as it was that winter when 2017 edged into 2018.

I was so cold, during the winter when I was fainting, that I took to wearing ski gloves. Even then, my finger tips would feel pinched and painful. Red and freezing once I removed the gloves indoors. One night, a cashier at the liquor store by my apartment made fun of the gloves when I had taken them off to open my purse and pay. “Are those boxing gloves?” he asked. “Are you going to fight me?” I shook my head and explained that my hands were cold. He looked delighted. “Don’t get into any fights now,” he called as I walked through the door. Around the same time I ran into an old colleague at a panel on Italian Workerism. I hugged him, and he flinched. I was so cold to the touch that it had shocked him. He asked if I needed a sweater, and I explained that I was already wearing two, plus a coat, and a hat. My husband yelped, “Don’t touch me,” one night when I got into bed and snuck my feet over to his for warmth. It was a long winter. The first snow fell in December, the last of it in early April. New Years Eve, two days before I was sent to Mount Sinai, was the coldest in one hundred years. The cold and the falling seemed one and the same, to me. Walking through my front door and onto the street felt, every time, like the strength was being sapped out of me. The hot, close environment of subway cars brought on dizziness. The northern winds sweeping down the canyons of dark streets flew into my clothes. I tripped constantly. I slipped in puddles, on ice, in snowmelt.

It is when winter hits New York that I am most inclined to tell people that I hate it. People talk about New York being ugly, but it’s hard to countenance this when you don’t live here. I had never believed people when they said the city was ugly, I couldn’t believe a place of such cultural importance could be genuinely ugly. Not until I began to live through New York winters, the way the gray sucks the marrow right out of you, the snow which purifies everything until twelve hours later it is covered in the black scum of pollution and yellow patches of dog piss, the smell of piss in general, and garbage, always garbage, frozen in bags on the curb.

The literature of the English language begins in the cold. Old English possessed words for the winter that we have shrugged off in Modern English: ‘winterbiter,’ ‘winterburna’, ‘winterceald.’ ‘Wintercearig,’ literally ‘the cares of winter,’ was a concept so familiar only one word was needed to express it. When we talk about spring and summer now, so many of the ways we have of speaking about it are about the adornment of the earth with greenery. What we suggest when we do this is that summer is a kind of costume the world wears, beneath which is the body of the earth. In winter, we see the body naked. These are the months when nature is arrested. It is the period between death and birth, when both the land and the lives we lead on it are halted by the cold.

Anne Carson writes, “To fall after all is our earliest motion. A human is born by falling, as Homer says, from between the knees of its mother. To the ground. We fall again at the end: what starts on the ground will end up soaking into the ground forever.”

My grandmother had a fall in her final year. She was on her patio, gardening, and suddenly she was on the ground. She was taken to see a doctor. A healthy, no-nonsense woman, the fall transformed my grandmother. She became weaker, and more fragile. Shortly thereafter she was diagnosed with cancer. It was all through her. The doctors told us she had six months, but she died in six weeks. I do not remember when, precisely, we found out about the cancer. It didn’t seem to matter. What mattered was the fall.

This was all in my mind, this string of connections—falling and embodied cognition, swooning and melodrama—when, in February, at the end of the winter, I found a lump in my breast. This is why, I thought as I touched the lump. The fainting really had been an illness, it was not embodied metaphor, it was not bodily articulation. This explained it all. Of course. I had cancer. I lived in this terror-logic for the next fortnight, through doctors’ appointments, ultrasound, biopsy. But in the end, I didn’t have cancer. It was nothing. Just a change in the tissue of my breasts. As meaningless as anything else.

The child psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott once wrote a paper called Fear of Breakdown, A Clinical Example. He contended that when a patient expressed a fear of breakdown, it was due to an experience of breakdown earlier in life. “A previous early breakdown occurred at a time when the ego cannot organize against environmental failure,” he wrote. “Environmental failure disrupts the ego defense organization and exposes the individual again to the primitive anxieties which he had, with the help of the facilitating environment, organized himself to deal with. This leads to an unthinkable state of affairs.” In other words, everything inside a person defends against breakdown, and fear of breakdown is characterized by particular feelings, or “primitive agonies.” Winnicott described these “primitive agonies” as the fear of having no orientation, having no relation to the body, complete isolation, the feeling of “going to pieces,” and falling forever.

I felt foolish and afraid when I fainted. The fainting brought about a lack of orientation, a sense of estrangement from my body. I felt, of course, like I was going to pieces. The dizziness kept on, no matter how much iron I took in, or water I drunk, my only diagnosis “weak with no known cause.” This weakness seemed to imply something about my character. I thought of how I was behaving in the same terms people use to deride melodrama: trite, silly, exaggerating. The fear persists even now: that by telling you about this, I am again being melodramatic, that I am trite, and silly, that I am exaggerating.

In a 1954 paper, Winnicott argued that it was normal and healthy for a person to “defend the self against specific environmental failure by a freezing of the failure situation.” Freezing, he says, as though to stop oneself experiencing the events of ones life by entering a kind of wintertime of the mind. It is the slipping away of the self from the life it’s living, into a psychic season where nothing grows, and nothing moves, where everything is an outline, an abstraction. Winnicott concluded, “There is no end… unless the bottom of the trough has been reached”.

Or, in another person’s words, the end arrives when you figure out “what’s happening between your head and your heart.”

The falling stopped when winter ended. It stopped not long after my mother-in-law died, somewhere around the last snowfall of the winter, and a trip, a drive across the desert from Las Vegas to Los Angeles. During that drive, crossing the San Gabriel Mountains at dusk, I saw eucalyptus trees as the car crested the peak, and was overcome with such a burst of homesickness for Australia that I burst into tears. But when I think about it carefully, I can see that when it really stopped was late March 2018, when my husband and I went to an office building downtown, progressed through security, a pat down, took an elevator up, handed over our papers, kept our phones in our bags, and were called into an interview room. In that interview room we were questioned about when we met, and what our first date had been like, whether my husband had gotten butterflies when he first saw me, on what we thought of one another’s families. A day when my husband explained that he loved me, that his mother had died a month earlier, and we had been through so much. When the interview was over, I was granted permanent residency in the United States, for reasons of marriage to an American citizen.

When we got downstairs the weather was dismally cold, but we were giddy. We could do anything. We walked across Manhattan, bought an enormous number of snacks, and went to the movies in our fancy interview clothes. We spent the night getting drunk on pink gin. There’s a photograph of me that my husband took that night, in which I look happy. Because it has a simple answer, after all. The ground never felt stable, has never solidified, but the falling stopped when I knew I was staying.