Go Forth is a series that offers a look at contemporary literature and publishing, started by Brandon Hobson and Nicolle Elizabeth in 2012.

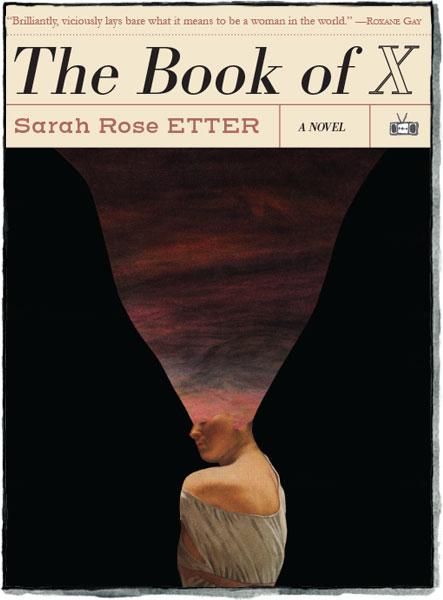

I first read Sarah Rose Etter’s language-up fiction years ago in stories that cut straight to bone, included those collected in Tongue Party, a chapbook published by Caketrain. Since then I’ve been waiting for a full length work and The Book of X proves that the waiting was well worth it. We often talk about world-building in novels and Etter has done so brilliantly here and with distinction. It is a strange, uncanny world, that features the strange and broken body of a strange and broken young woman named Cassie, the narrator we simultaneously pull for, are fascinated by, and want to protect somehow. This is one of the most visceral books I’ve ever read and one that stays with you long after you’ve read the last page.

THE BELIEVER: How did The Book of X start? One opens it up and is immediately struck by the form, short fragmented pieces, interspersed with a collection of facts and visions. And of course, the narrative starts from the first sentence, full of information and history. So, how did it all come together? The story, the form, all of it.

SARAH ROSE ETTER: Putting this book together felt like stitching body parts together, weirdly. Initially, I had this narrative about a girl named Cassie who was born as a knot, but her life was so tragic that I was looking for ways to give her and the reader breathing room. One of the challenges of writing a dark book is there’s the chance you go so far that the reader can’t stomach it, then the narrative becomes alienating. I can think of a few books that have done that to me – been so massively intense that I could hardly stand to read them. I didn’t want this book to go that far.

The visions were pieced together throughout as a system of escape for Cassie that eventually turns on her. She starts out imagining a world that is better than the one she is in—but as she grows up and gets a job, it becomes clear her station in life is not going to change. That’s when the visions she has stop being an escape and start to really exacerbate her mental state, eventually turning on her.

I’m glad you brought up the facts. They play a crucial part in creating breathing room for the reader. I’m a nerd at my core, always watching Planet Earth or documentaries, and being struck by the poetry in facts. For me, the facts serve as way for Cassie to understand the cruelty of the world around her—she is a character grappling to understand, to make her own world make sense, so the facts felt like a way I could show that side of her. They were also just incredibly fun to research and piece together. I tried to create small narratives within those pages too.

BLVR: Your character, Cassie, is born with her stomach twisted into a knot, like her mother before her. How did this come about/where did you get this from? Have you been interested in the grotesque for a long time? Are there particular books and writers you’ve gravitated toward because of this interest?

SRE: When I look back at it, the idea for Cassie being born as a knot might have started with a few Louise Bourgeois pieces I had seen—women who were twisted up the way her mother, a tapestry repairer, twisted fabric in the river in France as she was cleaning them.

Much of my writing, I think, wants to be sculpture—I want always to break through the page and create a scene so vibrant it becomes 3D in every way—emotionally, lyrically, visually.

As for the grotesque in fiction, I’ve always been pulled toward books I probably shouldn’t be reading. When I was really young, I was always reading V.C. Andrews and I accidentally bought a copy of The Story of O at a yard sale. The version of that I found was very nondescript—just a white book with black text on the cover. I remember reading that at a pretty young age, both horrified and compelled to finish reading it. I remember the first time I was given a Sylvia Plath poem in an English class and that I understood it within minutes—her darkness and obsession with death, specifically, were very easy for me to understand.

As I got older, I started really getting into darker, weirder work—not necessarily grotesque, but Donald Barthelme, Nathanael West, Blake Butler, Jenny Erpenbeck, Grace Krilanovich, Selah Saterstrom, Brian Evenson, Samanta Schweblin.

The through-line, I think, for all of these works is that there is honesty in the visceral. Writing the grotesque and the body both allow us to shed a lot of pretense—we’re all ultimately just blood and bones, and I do think there’s an intimacy to exploring the dark side of the human condition. To unsettle ourselves and to unsettle our readers is part of confronting everything—the world around us, the societal systems we live within, life, love, birth, death.

I do have some limits though. Blake Butler recommended a book to me that I’m still not over: With The Animals, by Noelle Revaz (Dalkey Archive). There’s mud and blood and animal cruelty—that one I had to take a few deep breaths before finishing. But I do feel drawn to work like that—work which makes me feel, viscerally, the writing in my body, and electrifies me.

BLVR: I know that visual art is very important to you and it’s interesting to see how Louise Bourgeois might’ve served as inspiration for Cassie. I’m also interested in your use of the word “sculpture” in describing what you want for your own writing, how you’d like to be read/experienced. Can you talk a bit more how the visual intersects with your own writing? When I think of sculpture I think, of course, of chiseling something from one form into another. Is this how you compose fiction? The Book of X?

SRE: When I sat down to write The Book of X, I just had this idea in my head that I wanted to write a book that had never been written before. For me, that meant exploring surrealism in the writing, and creating a texture from alternating the narrative with facts and visions.

I am fairly obsessive about visual art and movies—I took a lot of inspiration from Louise Bourgeois, Carol Rama, James Turrell, Suspiria, The Favourite. Seeing the Carol Rama retrospective at The New Museum by accident one day, I was struck by how much she moved between forms—she wrote, painted, created canvases that really bulged out into life, almost like tumors protruding.

I do hope my writing carries some of those qualities—that by giving the reader strong visualizations and visceral reactions to the imagery, I might be creating something beyond the page. That sounds so egotistical to want, doesn’t it? But sometimes, it feels words aren’t enough to transmit all the ways we exist in the world, all of our suffering and anguish and beauty and pain. That is why I feel so pulled toward surrealism—it gives my work the ability to extend beyond the page, I hope.

BLVR: I don’t think it sounds egotistical, no. And you’re right; language is a dull instrument for transmission almost all the time. That said, what else do we have. Speaking of what we have, how important is place to you? If I say the word, “Philadelphia” what does it mean to you? In general and how it informs The Book Of X? What about San Francisco?

SRE: A dull instrument is such a great way to put it—how do you put into words how the heart feels when you fall in love? Or the real depths of depression? I don’t know that those things lend themselves to language—it’s a constant attempt to describe what is probably indescribable. With this book, which deals so much with pain and trauma, it really struck me how imprecise those two words are. If I say I am in pain, that can mean anything—it could mean I’m having a slight ache in my toe or I am in debilitating agony and unable to move. The word “pain” is such a perfect example of how much language is only scratching the surface of the human experience.

As for place, that’s a little more difficult to answer. Philadelphia was my home for ten years, and when I moved away, it felt like I was a tooth being ripped from the gums. I knew I had to try something else and push myself, which is why I moved to San Francisco. There are small nods to Philadelphia in the book – the grittiness is in there, certainly, especially in Part II. San Francisco is more complicated—I have only been here for a year, and I find myself pretty unhappy here. The city feels like a fault line—the disparity between wealth and poverty here is so much higher. You have people paying thousands of dollars in rent to live on streets where people are homeless and bleeding and suffering. I find it almost unbearable to leave my house some days because it feels entirely inhumane and unacceptable that someone is suffering below my window. There are certainly beautiful things here—the ocean, the weather, the people. But it feels unethical to be here, and to exist within this specific dichotomy. It did help to live here during the editing process though—after Two Dollar Radio accepted the book, I really went into an isolation to edit it here. I holed up in my apartment and just eviscerated each sentence. I was reading a lot of Brian Evenson and Katya Apekina’s The Deeper The Water The Uglier The Fish. The lines in both of those works are so sparse and precise that it made me really dig into my own work. So San Francisco did have an impact in that way—it gave me the room to edit.

BLVR: Where do you go from here as a writer? What’s next for you? I find myself thinking of The Book of X’s Meat Quarry quite a lot and am curious about other worlds and landscapes you might explore.

SRE: I’m working on a short story collection where each story is tied to a work of art in some way as the inspiration. That’s been fun, mostly because it gives me the chance to play with the visuals. I’m also working on a novel, but that’s more of an exploration of what is happening in San Francisco. It’s a little less surreal since it’s based more in the now, but I’d also argue that what’s happening in this city has an element of surrealism. I do feel like I am inside the mouth of capitalism out here, and watching what it does to humans and how we try to survive and live within it when it is moving at warp speed is quite different than anywhere else in America. It often feels like an invisible hand around my throat. I’m not sure if that’s as surreal as a meat quarry, but it feels close.