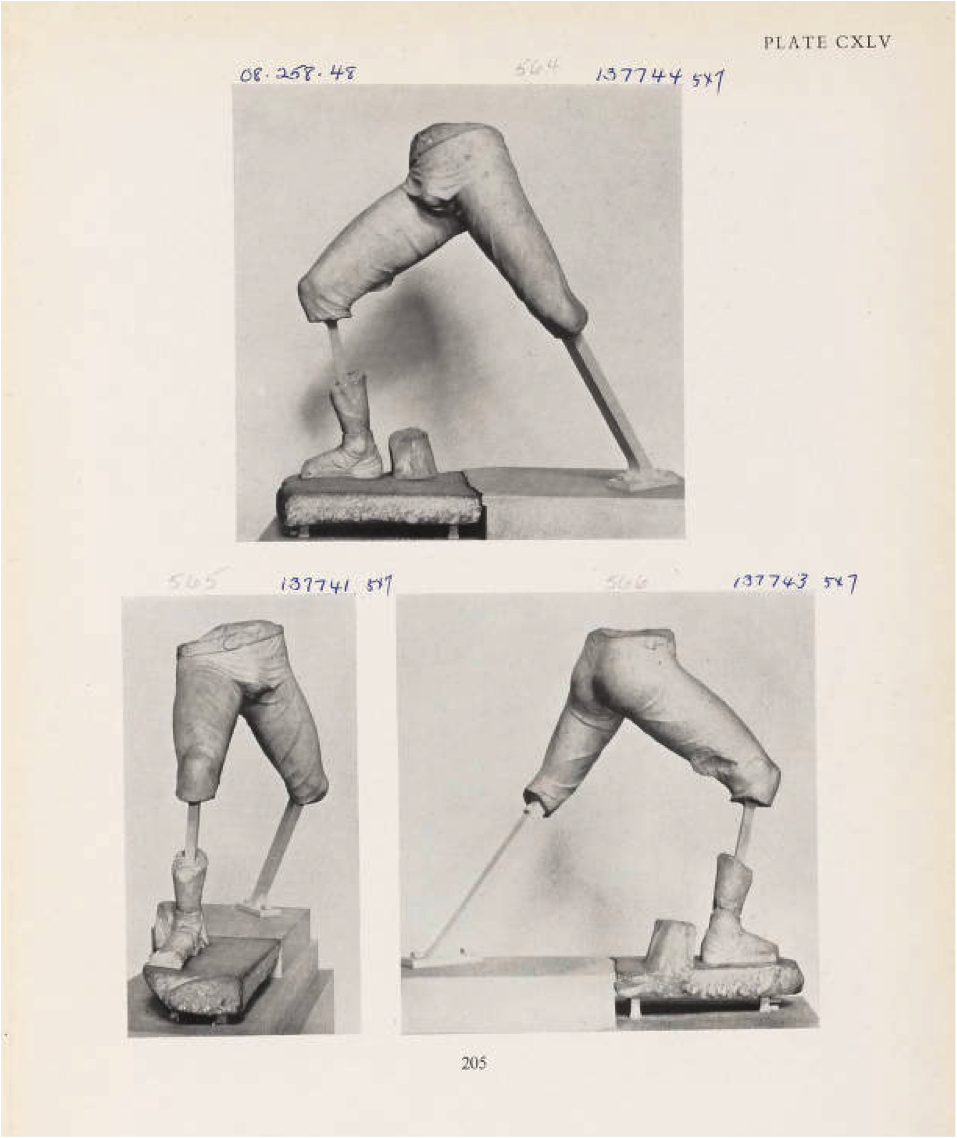

Have you ever craved an image like you wanted to eat it? This kind of craving isn’t quite for the object itself, but the feeling of your eyes at work with it. The memory of the sight alone isn’t enough. Maybe what you saw turned you on, or maybe it comforted you. Maybe it reminded you of someone, even though there was no concrete resemblance, just a stray jolt of recognition. For the past year, I’ve been monopolizing a bench in the Met’s sunny Roman sculpture court, where I can stare at a statue that’s missing everything from the waist up, and whose legs have been reassembled with metal poles. Although less than half of the statue’s body remains, I’ve been trying to resist the urge to put him back together, or to imagine the torso and face that have been gone for millennia. I’m pretending that this broken form is exactly how I am meant to see him. His severed waist shows a rough, grainy marble inside that contrasts against a smooth surface and carefully articulated details: wrinkles in his pants, tiny knots on his sandals, and a chain belt just below the break. If he were complete, I might not have noticed these things. I think I like him better broken, though I know him no other way.

Sometimes looking at art is like looking at a new love interest. It’s an attempt to find a balance between understanding the object (of affection, or art) for what it is, but also for what your own story brings to it, and how meaning grows between both of your realities. You try to be patient, let the object reveal itself at its own pace, and be careful not to project so much that you are blinded. I think about this broken statue when I’m not at the Met the way I think about a crush; he’s even the wallpaper on my phone. Sometimes I look at him so hard, that when I leave the museum, it’s as if I am seeing through a filter: broken-statue-tinted glasses. I see his shape everywhere: he’s in tree branches, a mannequin in a dumpster, a subway poster that someone has torn to cut the feet off of a model.

Before I put this warrior in places where he was never meant to be, let me tell you what I know: The Marble Statue of a Fighting Gaul, is what’s left of a statue of one Celtic soldier, who Romans faced on their borders during the late 3rd, or early 2nd century BC. Historians think that the original may have included a Roman opponent, standing in front of him on the same marble plinth. To celebrate their victories, Roman artists often made sculptures of their enemies in the nude or in vulnerable poses, but this one is different. The remaining pieces show that the Gaul persisted in his attacking stance, nowhere near defeat. Now he’s lost not only his opponent, but everything above the waist, and his back foot. His front foot is still attached to the original base, but there’s a metal pole where his shin used to be, which makes it look as if he’s wearing a modern prosthetic. The back leg is supported by another pole, which disappears into a modern platform made level with the front, ancient marble. My warrior has one foot in the past, and one in the present.

It’s often natural to read the information plaques on a museum wall before we actually look at what’s in front of us, and this isn’t necessarily the wrong way to look at art. But it’s also too easy to dismiss our own responses if they conflict with the artist’s intentions, or the analysis of an expert and I want to defend my hunch that the Gaul is whole in his present form, or at least that there’s something valuable in seeing him this way. I teach writing at an art school, and I’ve noticed that students often jump to the big ideas in their essays—symbolism, historical context—and forget to describe the art itself. They’re missing the concrete evidence that supports those big ideas. A student might argue that a painting depicts the artist’s inner turmoil, but I want to know where exactly in the brushstrokes that turmoil has taken shape. What did you see that lead you to your ideas? I ask. We go back to the surface, and work from the top down. I call it a context game: ignore the authority of the historians, forget about time and intention, just for a moment, and focus on what’s in front of you. Besides the art’s own origins, in what other contexts can we responsibly (or irresponsibly) place it? I write the words of critic Sylvan Barnet on the chalkboard: “Art ought to enlarge feelings, not merely confirm them.” It’s important to understand a work of art in terms of its own origins, but let’s not forget to consider what the object is doing in front of our modern eyes, here and now. We can amend the past without erasing it.

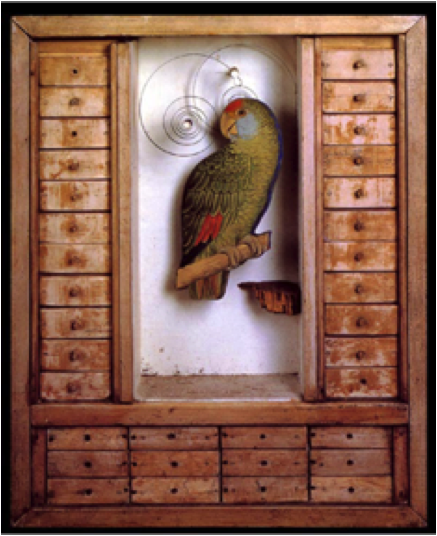

When I play the context game with myself, I can find the Gaul’s pose in my own body. Here is my yoga teacher touching my knee as she walks past me: Move your foot forward so that your thigh is almost parallel to the floor. I imagine that the metal poles are not there to repair the original, but they have revised it. Any sign of antiquity is only a reference. Maybe the artist is one of the surrealists, like Salvador Dalí, whose 1936 sculpture Venus de Milo with Drawers transformed the famously broken goddess into an “anthropomorphic cabinet,” as he called it, by installing drawers with pom pom handles into her body. The Gaul’s missing torso could have been made of anything. Imagine the head is medusa’s, and the snakes were real—a living performance. The context game can be played like a game of exquisite corpse. Imagine his arms were once wings, and now the ancient wings have found new homes. Maybe some found their way into another piece of art. I see them across town, in MoMA’s collection, arranged in a tiny diorama by the assemblage artist Joseph Cornell.

What’s missing from the Gaul is exactly what makes so much space for the imagination. He is still a warrior, but today his mutilations look more like the casualties of modern war: amputations after landmines, or shrapnel. He’s one of the men my father knew when he fought in Vietnam, who he still sees at the VA today. I’ve heard stories about the shock right after limb loss, and I can only imagine the scene: a soldier comes home, someone who loves him is advocating for him, on the phone with the insurance company, printing out studies on prosthetics for reading in bed. It’s what they can do while he learns the new map of his body. There is physical therapy to walk again—maybe someday achieve this warrior’s pose. I want to picture the real moments of recovery, but of course I cannot know his.

I was at the Met last summer on the weekend of the Charlottesville Riots, which had erupted over the removal of a Confederate monument. The Gaul colored my gaze as I scrolled through my news feed. He became an image of brokenness in the middle of our broken country; but it could have been any image of brokenness, since I was looking for them. Right-wing protesters along with our president were arguing that we must preserve our history, but the preservation they still continue to call for privileges certain histories over others, and dismisses how these monuments speak to the present communities around them. I thought of Barnet’s call for art to enlarge feelings: what kind of spaces should be made for today’s feelings, while freshly validated Neo Nazis and white supremacists rage through these neighborhoods? I don’t know if there is a way to reframe the monuments without removing them. Maybe we can only make space if they are absent.

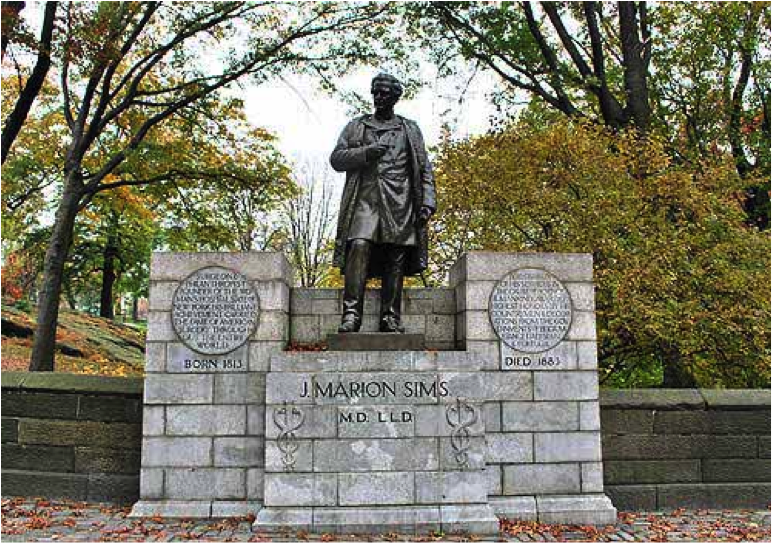

Months after Charlottesville, and with the national problem of monuments far from resolved, I visited Doreen Garner and Kenya (Robinson)’s exhibition White Man on a Pedestal, where Garner created a replica of a statue of the 19th century “Father of Gynecology,” J. Marion Sims. The monument to Sims has held court in Central Park since 1894, along with a plaque that refers to him as both a surgeon and a philanthropist. This tribute overlooks that Sims performed experimental surgeries on enslaved, and pregnant black women. He did this often without anesthesia, let alone consent. Garner’s version places Sims in a silicon cast, to be dissected in an operating theater installed in Brooklyn’s Pioneer Works. “Meat” sculptures surround him, including the severed leg of a white male. The skin on one side is ripped away down to the bottom of his foot, revealing red fleshy muscle made of cereal and beads. It is repulsive and bloody, but still sparkles under surgical lights.

In mid-January, New York’s Mayor, Bill de Blasio, announced that the city would relocate the Sims statue to The Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, and take steps to inform the public of Sims’ history. There are plans to add information plaques where he stood, and to commission new artworks that dialogue with the history of medical experimentation on people of color. For a moment I picture Garner’s meat sculptures in this space, but immediately know that it would be a terrible fit, and could cause even more pain. The neighborhood group East Harlem Preservation has proposed that a monument be dedicated to one of the many African American or Puerto Rican doctors—Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias or Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, for example—whose contributions to medicine benefited the East Harlem community. “We don’t need any reminders of [Sims’] barbarities,” they wrote on their website. “We bear the pain and burden of intergenerational trauma every day.” Maybe one condition of the context game is to recognize that there are limits to reentering traumas of the past. When playing with context we can’t forget the importance of the personal, of ancestry, and identity. I have to remind myself, this is hardly a game at all.

Sims’ history can be unpacked, stripped of reverence, and retold. But what parts of the gruesome truth should remain visible, for families who stroll through the park, who may carry traces of this history in their own heritage? Some have suggested that the new monument be a tribute to the three main women who Sims used for his experiments. We know their names: Anarcha Wescott, Lucy Zimmerman, and Betsey Harris. It’s hard to know who they were besides the victims of slavery, but there is always more to see inside the frame of a story. Here is what we know: they were young—all three under twenty years old—and they were mothers. We know that women like them worked from sunrise to sunset, even when they were pregnant, often right up until the day they gave birth. They were expected to go back to work as soon as they could stand. We also know that many enslaved communities nurtured rich cultures of self care and medical practices to help withstand the hazards of everyday life, especially for those who were disabled, elderly, or pregnant. We know that medical discoveries that we still use today would not exist without Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey. The poet Bettina Judd channels Betsey Harris in her book Patient. “Sims invents the speculum / I invent the wincing,” she writes. “the if-you-must of it / the looking away / the here of discovery.” Judd recognizes that credit is due. These women deserve some form of authorship.

When a wound becomes a metaphor, its meaning depends on the body to whom it belongs. The Fighting Gaul shares a room with ancient goddesses, and my context game is again different in front of them. Maybe my projections have become too much, and I’m placing my own body in it again like a dress that doesn’t fit. I can’t inhabit all of this. Looking around the room, it’s harder for me to pretend that broken statues of women are outside of time, and injury. While I can shift my focus to pretend that the Gaul is an intentional representation of something modern, I can’t help but think about what a female statue endured. Was her marble breast chipped during an earthquake? Was it only the weather? Or were there teenage vandals; were older drunk men trying to flaunt their sexual bravado, conquering a flawless woman by defacing her? An armless woman can’t resist. A headless nude is sex without consequence: no mind, no mouth, and no eyes.

A broken form of a woman still represents beauty, not disability. The Venus de Milo is wounded but persists in her elegant pose, and her original shape becomes all that we look for. In his essay, Nude Venuses, Medusa’s Body, and Phantom Limbs, disability studies scholar Lennard J. Davis writes of an “amnesia,” in the face of mutilation. “This looking away from incompleteness,” he writes, “is the tip of a defensive mechanism that allows the art historians still to see the statue as an object of desire… The critic’s aim is to restore the damage.” Rather than as an object of desire, can we face a broken goddess as a representation of recovery? Can she contain both meanings? I want to see her face evolve. The goddess’s gaze might appear serene, but to consider her new wholeness, perhaps it is an expression of annoyance. She is tired of us overlooking her scars, and her journey of recovery: Face me and love me for what I am, I can almost hear her whispering into the museum’s crowded halls. Aristotle, who died over two centuries before the creation of most of the statues in the Roman sculpture court, saw the female as an incomplete, or deformed male. He compared female desire to the desire of the shapeless. “Matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful,” he wrote. What would he think of these women now? Some bodies don’t yearn for new forms, but seek to be recognized completely in their own. I also wonder how I might read this as a woman who claims to have a crush on a broken statue of a man. Does the lover want to possess the beloved, or become the beloved? The same could be asked of art lovers and art. I don’t want to bring the Gaul home with me. I don’t want to become him, or take on his form, but I want his light to stain my eyes, and I want to keep it there.

British artist Marc Quinn’s Alison Lapper Pregnant, resembles the limbless statues we revere so much, but this one depicts a woman who was born this way. It was erected in Trafalgar square in 2005, among statues of lions, and military men. Lapper was born without arms, and with shortened legs. She posed for Quinn when she was seven months pregnant, sometimes sitting in the same position for more than fourteen hours at a time while waiting for the wet plaster to dry around her body. As an artist herself, she was involved in the direction of this monument, and made sure the depiction was not of pity. She’s also done her own photographic self portraits, often posing as a modern day Venus de Milo. “I never heard anybody say the Venus de Milo is disabled,” she said in an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2006, “And yet if you look at my shoulders and at hers we’re very much the same. Why is it we can look at a sculpture that people think is beautiful, but nobody ever looks at disability in the same light?” The statue makes a bold challenge towards taboos surrounding disability and sexuality. Here is a woman who speaks to us from multiple categories: artist, model, goddess, single mother. In her memoir, My Life in My Hands, she wrote that she miscarried four times in her 20s. Finally, when her latest pregnancy lasted, her boyfriend pressed her to get an abortion. She broke up with him, and gave birth to a healthy baby boy. With the help of occupational therapists, she learned to change diapers, and breastfeed; her feet, mouth, and chest were limbs enough to hold him.

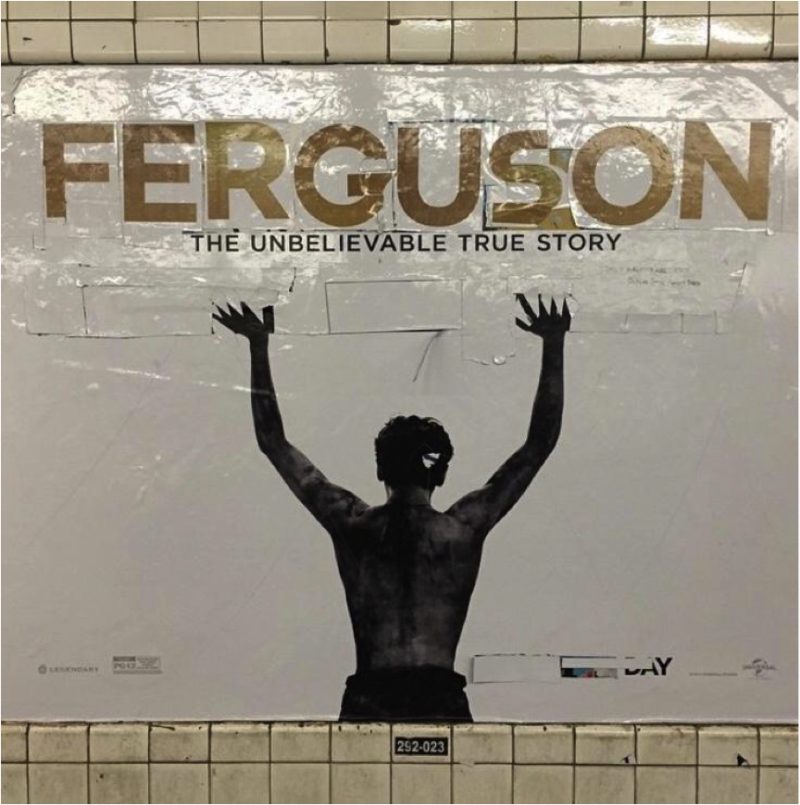

A high school version of me liked to take pictures of my feet. I only understood my body in pieces then. I wanted to cut away the parts that were new and unfamiliar: new breasts, new thighs—new shapes. Selfies were harder then, on film, when I couldn’t immediately see the result, and had to trust that I was contorting my body around the camera just right. Today, when I’m walking I look for images of incompleteness and asymmetry: cracks in the sidewalk, a three legged table. I keep the pictures of these street fragments in a folder on my phone called “Dismembered City.” What if I told you I thought that they were comforting? If broken things linger long enough, they grow into their new shape, find a new function. They become the face of the city itself, and we forget that their lives were ever broken. People pick at the plastered posters on subway station walls, revealing layers of old advertisements underneath. The resulting collages are sometimes uncanny: the mouth torn off of Kevin James’ face reveals Yayoi Kusama’s dots underneath. I saw the letters in the title of an action movie rearranged to say “Ferguson,” right after Michael Brown was killed there by police. Ads are everywhere on a New Yorker’s commute, and it’s refreshing to come across one that’s been cleverly (or even not so cleverly) vandalized. It feels like rebellion, and puts these spaces back into the hands—and eyes—of the public. To me these ads are better broken.

I admit that on the day when I first noticed The Gaul, I’d been feeling depressed about a failing relationship. I’d gone to the Met after work, because I thought that to see really old things—older than the complications of dating in New York—might help. People often say that the solution to heartbreak is perspective. They say that pain is insignificant amidst a larger context. But my heartbreak didn’t feel small. Maybe I didn’t want it to feel small. When I walked into the Met, it wasn’t the age of the objects, but their present state that struck me: broken, exposed, vulnerable. That week my students were reading Joan Didion’s essay Why I Write in which she says that an idea takes shape not in the mind, but on the page. “It tells you. You don’t tell it,” she writes. “What is going on in these pictures in my mind?” is the question she hopes the writing will answer.

I remember imagining that some of my students could even have been reading their assignment in that moment when I first saw the statue. Maybe they were savoring the question, What is going on in these pictures in my mind? like I savored it. Maybe I thought of my students more than I should, for someone who gets paid so little, someone who should’ve been focusing on her own writing. But I was heartbroken over a man who had made me feel invisible, and it was comforting to think that something I had given to a tiny piece of the world—even a homework assignment—could be on anyone’s mind. The object of my affection had accused me of taking our short relationship too seriously, and I felt silly to grieve over a love that had never been named. He’d been clear that he wasn’t looking for a relationship when we’d met, but I thought I would wear him down, teach him that what was here could be love. How does intimacy happen? It tells you, you don’t tell it, right? He was a bad student, I thought. Then again, he wasn’t my student.

When I started seeing resemblances of the Gaul out in the world, I tried to carry Didion’s What is going on in these pictures in my mind? around with me, as if it were no longer a sentence, but a protective charm in my pocket. I wished I could think about the page the way I thought about the person who had hurt me. I wished I could listen to it tell me. Those listening skills that you thought were so strong? You have to relearn them again and again, with each subject, each intimacy. I’d sit down to write and it was as if the keys were suddenly hot; I’d see Frankenstein’s monster. Images of severed, bloody limbs were what came to mind, no matter what subjects I had set out to write. They were in my dreams. And even when I started to watch them, and find them in the world outside of my head, I thought that I was delusional for wanting to make connections between topics that had nothing to do with each other. What is going on in these pictures in my mind? The answer to this question, and the way to avoid being overwhelmed with the pictures, is to look directly at them, collect them. My crush was on the monster, on the limbs, and it scared me that I was seeing them everywhere. I still see them everywhere, but I’m no longer afraid, maybe I’m in love.

I want to bring time backwards, to before the Fighting Gaul was even a body. Catch the fragments in the moments of their creation, instead of their destruction. Maybe the artist started with the front foot, the one we still have today, and went on from there. These are the pieces long before the possibility of either brokenness or completeness. In front of me is that impulse to make something out of nothing. The artist starts with a hunch: create! There are warriors in the marble.