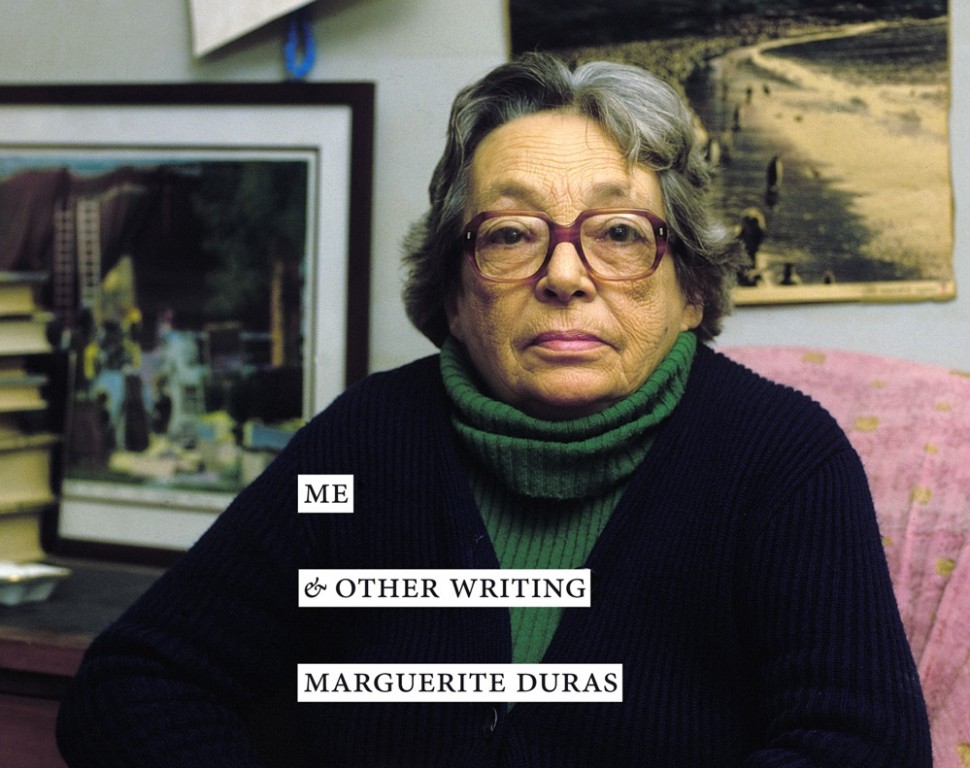

Marguerite Duras writes about translation in Me & Other Writing (Dorothy, a publishing project), saying, “a book is never simply translated, it is transported into another language.” When I had the chance to interview Emma Ramadan and Olivia Baes, the two translators behind Me & Other Writing, we talked about their translations, both together and individually, as well as their relationship to Duras’s writing. The two met while graduate students at The American University of Paris, where they first began to translate Duras. In the fall of 2020, Emma and Olivia each published individual translation projects; Emma published two translations from French-Moroccan writers, A Country for Dying by Abdellah Taïa (Seven Stories Press) and Straight from The Horse’s Mouth by Meryem Alaoui (Other Press) in September, while Olivia published Jean-Luc Persecuted (Deep Vellum) in August. As much as Emma and Olivia could speak to the effects of their co-partnership on their work and each other, I was interested about the effects that translating Duras has had them as readers, translators, and creatives. I wanted to know how Duras’s writing can transport a translator somewhere else.

—Sarah McEachern

THE BELIEVER: I wanted to ask each of you about your introduction to Marguerite Duras. How did you come to her writing before you started translating her?

EMMA RAMADAN: I had to read Marguerite Duras in a high school AP French class. For some reason, we were assigned Moderato Cantabile, which is a really complicated book for high school students who hardly speak any French. Even though I could barely understand the book, there was something about it that I found really powerful in its depiction of a wild, inescapable love or obsession, or whatever you want to call it. When I went to college, I took classes where we were reading Duras. Mostly we read The Lover, the classic Duras book. Every summer I would reread Moderato Cantabile as my French improved. I understood it a little bit more each time, and it just became more and more of an impactful and important book for me. When Me & Other Writing came out, I wrote that Moderato Cantabile felt almost like a premonition. I knew that something deep in me was resonating with the things in the book even when I couldn’t identify exactly what it was. My obsession with Duras continued from there, and I read more and more of her books, and my life started to intersect with her writing. It became more of a real connection rather than just a premonition.

When Olivia and I were doing our masters together at The American University of Paris, it came out pretty early on that we were both really interested in Duras. Once I was very close to Olivia—after I understood her genius and knew I wanted to translate things with her and keep working with her creatively—I revealed that I had been doing all this research into which books of Duras’s hadn’t been translated yet. There was this novella called Summer 80, which went on to become the second half of Me & Other Writing. And I sort of was like, Hey, I have this secret. There’s this novella by Duras that hasn’t been translated yet. Do you want to work on it together? And then we went from there.

BLVR: Olivia, how did you originally come to Marguerite Duras, and how did your relationship with her writing intermingle with the way that you took up this project with Emma?

OLIVIA BAES: What Emma’s describing was kind of what happened to me too. I was going to call it an awakening, because I had a really intense experience of reading Duras for the first time in college. But actually, it’s funny, because the first summer of my [undergraduate] university experience, I did a creative writing workshop, where I started what would then be my thesis, which is an unfinished novel. And my professor Darcey Steinke, an American novelist, came to talk to me after I read a passage and she was like, have you read Duras? You should read Duras. And I thought, who’s Duras? Which is kind of crazy because I was raised by French parents between Europe and the US, but did high school in the States. I didn’t have to do French in high school, so I grew up reading mostly English writing authors. But I didn’t even end up checking out Duras’s writing until two years after Darcey’s class. I took a post-war European fiction class with one of our mutual professors, Dan Gunn, who wrote the foreword for Me & Other Writing.

We read The Ravishing of Lol V Stein, and I was profoundly shocked by the book in a very personal way, kind of similar to Emma’s experience. I had this feeling that this writer would become, or had already become, extremely important in my life. For me, it was the way that she talked about this woman, Lol V Stein. There was some recognition there, and I read the book in a trance. The obsessiveness, the repetition and the way that she didn’t stop until she got to the core of a feeling or an emotion. I will always remember having lunch with two of my girlfriends after finishing the book and telling them, I’m electrified by this writer. I haven’t had many literary experiences where I want to read every single one of the author’s books.

After meeting Emma, even though we had other similar interests, I think that this kind of obsession we had with Duras was what really brought us together. When Emma approached me about translating her together, it just felt like a perfect fit. I knew that our passion was sort of in the same place, so that’s how it happened to me. That was my ravishing.

BLVR: When you were working on Me & Other Writing, were you geographically in the same place?

ER: Yeah, we did the first sample together in Olivia’s apartment, when we were both in Paris. We would work on it together, then we started sending it out. By the time it was accepted by Dorothy, a publishing project, we were in different places. They had asked us to make the book longer, so it became more than just Summer 80. We ended up doing a ton of research, and I was sending scans of all these books to Olivia, we would talk over Skype or FaceTime.

When we started translating, we basically split up the articles based on who really connected to certain articles. The chapters of Summer 80 we split up too, kind of randomly. Then we would look at each other’s drafts on Google Docs, and sometimes leave really passive aggressive comments for each other. We would always have FaceTime sessions where we might argue, but we also had nice things to say as well.

OB: Yeah, but it was definitely a long distance co-translatorship. We were in different time zones. We did our initial sample together in Paris in the summer of 2014, and then actually ended up translating the book in 2018. I think when we first got into it, we had this motor, which was just our obsession with Duras and her work, the way we had been touched by it in similar and probably different ways, as well as our friendship and wanting to translate together. I do distinctly remember within the first week of us starting to work on these articles, we both had similar revelations about how much harder this was going to be than we thought it would be.

At least for me, it was very painful in the beginning. I was thinking to myself, Wow, Duras is just… She’s kind of ravishing me again, but now in a totally different way, one that doesn’t feel good. So we had to find this rhythm of working together, but also, at least for me on my own, I had to really get into translating Duras. Initially that felt like a struggle, and I think that Emma and I helped each other through it. She was a great help during that part of the process. Knowing that she was going through it at the same time as me felt very comforting.

ER: You definitely helped me through this as well. It was a lot harder and easier than I expected it to be, because some of the articles in the book were never before published or newspaper articles that were never edited. There were things that literally didn’t make sense, and we would end up banging our heads against the wall. It quickly became a situation where we’d have to take a step back and just feel what she was trying to say, and then we worked backwards from there, as opposed to trying to dissect the words on the page.

I think it would have been much more difficult for me to give myself permission to do that if I hadn’t been working with Olivia. We both came to the same conclusion of like, the words aren’t going to make any more sense, but if we just sort of close our eyes and think about what she means, then we can write it in English. For me, it was a huge and really great experience to have as a translator that I would have been too afraid to do on my own.

Also, just the moments we had when we would read things out loud to each other, and we would be able to hear Duras. That was really special. Even though I could have read the translation out loud to myself, there’s something different about hearing it come out of somebody else’s mouth. And hearing the echoes on FaceTime, there’s something validating about translating with a partner like that.

OB: Yeah, I agree with all of that, and especially with what you just said about how sometimes we found meaning in the flow. I think both of us are very interested in rhythm. We both write poetry, and Emma translates poetry. I did my thesis on rhythm with Jean-Luc Persecuted, using theorist Henri Meschonnic’s A Rhythm Party Manifesto.

When we first started translating Me & Other Writing, like you said, the words on the page didn’t make sense if you started dissecting them in order to reproduce what Duras called “the literal reading.” I think that once you were in the flow, the other meaning, even if it was very fleeting, would crystallize. You could capture it there and be able to translate it in the flow, so to speak.

From the very onset we agreed that rhythm was going to be our guide for this translation, which for me is the equivalent to saying that Duras was the master of this translation. Her rhythm is so intrinsically hers. There’s no difference between Duras and her rhythm.

I felt like she was directing us. I felt like one of her actors, because she had this reputation of having people read exactly in her rhythm when they were acting out her texts. When the rhythm was lost, the acting was off.

BLVR: I’m really interested in how you’re talking about Duras as a director because, of course, she was also a filmmaker. Olivia, you’re a screenwriter. You touched on this a little bit in your translator’s note of Jean-Luc Persecuted, saying, “As his translator, I choose to follow this cinematic momentum, picking rhythm and emotion over the grammatical and syntactical rules we are told are ‘correct’ and cannot be broken.”

I wanted to ask a few questions about being a screenwriter and a translator, and now also feeling like an actor of Duras. How being more involved in films affects you as a translator, for Duras, but also with regards to Jean-Luc Persecuted?

OB: Absolutely, in fact, it’s really pertinent to what I just went through today. As Emma knows, I was just working on the audiobook for Jean-Luc Persecuted for the past two days. It was such an amazing experience because it confirmed my thesis and how I truly believe that rhythm is the vehicle for meaning.

As a translator, if you stay close to the rhythm, if you let yourself be carried by it and you don’t start to worry too much about what every single word means,if you just kind of flow with it, you will arrive at a meaning that seems to hail directly from the author. Like Emma said, it’s about feeling… It feels right. And you feel like you’ve gotten it.

Working on the audio book today and sort of acting out the book, it was like I understood Jean-Luc Persecuted the best I have ever understood it. That’s saying a lot because I’ve worked on it so intensely over the years—I’ve read it so many times, I’ve translated through several drafts, and have read over the text again and again. But there was something about reading it out loud, with a theatrical intent, and sort of completely letting go and just being in the flow of it, that sort of made it all come together clearly. And the meaning just came to the surface in this natural way. In order to communicate meaning in translation, you have to let that rhythm run through you. As a translator, I think that you have to listen, you have to be able to catch that rhythm, hear it, and let yourself be guided by it.

I think it’s the same with my film work. For example, when you write a script and you hear actors speak the lines, you can tell right away if they’ve kind of dialed into the rhythm in the original writing. If they haven’t, often, the meaning will get lost. For me, all of these practices have just been confirming the law of rhythm, how it enables us to access the deepest emotions and get them across to other beings.

Emma and I both know that sometimes just because one word means this other word in a bilingual dictionary, it doesn’t mean exactly what the author is bringing across. When you trust rhythm over the dictionary, you can enter this kind of a very mystical flow that was the author’s initial intention. It’s something I’m very interested in that I was so glad to see with the audio book experience this weekend, because it was like another layer of that same research I’ve been doing since college.

BLVR: Emma, touching on what you were saying earlier about what you gained from the experience working together, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your individual processes, and then how they’re affected by this collaboration?

ER: As an individual, everybody has the words that they like and the words they don’t like. We all have different experiences, because, of course, we’ve all grown up listening to different languages, different words, and different people talking. Certain words are just going to rub us different ways. Working with somebody else who also has a really intimate and intense connection with language showed me my own biases about what words I like to use, what words I avoid.

I think it was just a very different process from the start, because, as Olivia said, we had the same priority, which was to be guided by the rhythm and to make it sound like Duras and not like either of us. It’s obviously very helpful to be on board about a vision when you’re co-translating, but it’s still a process with constant negotiation. Mostly, choosing the texts was a negotiation because Olivia as a screenwriter is very interested in Duras’s film work and her writing about films. Ultimately, it became a different book than it would have been if I had been translating it on my own, but I think it’s a better book for having been translated by both of us.

OB: I need to mention that Emma is a Virgo.

BLVR: Olivia, what’s your sign?

OB: I’m a Gemini.

BLVR: Oh, of course, I was listening to you and I was like, she’s a Gemini. That makes perfect sense.

OB: I’m actually a double Gemini, which explains a lot of things.

It’s funny because I just had this conversation with Martí Albert, the sound technician who recorded the audio book. He was asking me what it’s like to co-translate because he wanted to compare it with what it’s like to be a co-director or a co-screenwriter in film.

With Emma, what was really good is that the way I work in every practice is sort of almost wholly based on instinct and intuition. Sometimes that can be a little extreme, I guess, because I become really sure of myself and trust my gut—without questioning anything. Once I got going with the Duras translation, I became so sure about so many things, and then Emma would say, Actually, no. That’s not how I hear it at all. When you do things on your own, you don’t have that person who’s reigning you in, whose instinct can be different than yours. And so it’s a little unsettling at first. We had our disagreements, mostly over those Duras articles, like ‘the’ or ‘a’, but I think that in the end it’s such a better book because of our working together. There was a point where we had integrated all of Emma’s comments, and she read the text to me and it was just like, Yeah, this is it. This is it. Our translating process seemed to be that I took it really far, Emma pulled me back, and together we got to this amazing in-between place that was Duras.

BLVR: I wanted to ask a few questions about how translating has impacted each of you as readers. After working with her language so closely in this project, has that changed the way that you read or interact with Duras now?

ER: I haven’t gone back to re-read our translation. That would be horrifying for me, I think. Except, I did thrust our Duras translation on somebody recently. I was trying to tell them about this one particular description of the sea that I remembered really loving, and when I was trying to find that one description, I was like, Oh, there are actually a lot of descriptions of the sea, and I love them all. I don’t think I’ve read any other Duras since the book came out. Olivia and I are maybe trying to embark on another Duras project shortly, we’ll see.

In terms of how it’s influenced me as a reader, when I read translation now I’m always sort of attuned. My brain starts looking for the things that give it away as a translation, which is not a fun or interesting or productive way to read a book. And so I try to put that out of my mind. Especially after translating this Duras book and after working with Olivia so closely, the whole experience has given me a new appreciation for how rhythm works and how meaning gets filtered through the rhythm of the words.

For instance, I told a friend to read Clarice Lispector’s Near to the Wild Heart, and he was like, I cannot get through this book because I keep reading these sentences that don’t make any sense to me. When he pointed out this one particular sentence, I had actually underlined the same sentence in my copy. Even though it had really meant something to me when I was reading the novel, I could not for the life of me explain what it meant. I told him, you just have to feel it. You feel it and that’s how you understand it.

Sometimes it’s not about the words at all. What the words carry within them can make so much sense to me and resonate so deeply with me, even if I can’t parse it out for you and explain to you what it means. Having that experience with the Duras translation where it would mean something so deeply in me, but then when Olivia and I tried to put it on a page, we were like, This is impossible. What are we going to do? The whole thing reoriented my appreciation for the way certain writers work, certain books operate, the way that meaning can be communicated through certain books, and what meaning looks like to certain people. And that’s been the biggest influence for me.

BLVR: I definitely feel like that with Lispector too. Her sentences can both make no sense and also tons of sense. When Gertrude Stein does the same thing, it’s just never worked for me. I find Tender Buttons so jarring and confusing. With Lispector though, I can totally understand what she’s trying to convey, especially Água Viva.

OB: It was the same way for me when I read Lispector during college. I was underlining whole sentences because they felt so clear when I was reading them in the flow. Actually, I feel quite similar to Emma in that way.

It’s funny because when you start working on films, you can end up watching films in a totally different way, where, without wanting to, you’re like, Yeah, there’s a sound guy there. The actor is standing under a light on the right. The magic can get stripped away, and you see the film as a set, so that you are transported less often. When you are translating, you are kind of looking at the set too, you are looking out for the tone and whether it sounds natural and stuff like that. But translating someone like Duras, you get this deep appreciation for the genius of authors, their magic, what they mean, and how they convey that meaning through their particular rhythm. Certain writers spin their web in such an amazing way that their meaning resounds throughout the entire book.

When I first started recording the audiobook for Jean-Luc Persecuted, I felt very self-conscious, and then once I entered and was carried by the rhythm, there were so many things that came to the surface. I stumbled into these repetitions that Ramuz uses. An image used in the second chapter comes back in the ninth chapter like an echo of meaning, and I don’t know if something like that is even intentional. I think it might be subconscious, honestly. An accident, part of the magic. Reading the novel out loud, it’s the first time that some of these things crystalized for me.

With translating, you become so aware of language, and you have such a reverence for language. Every author is different, and conveys their magic, their secrets about life, through language in a different stylistic way. When you start translating, you begin to have this acute awareness of how exactly that meaning is threaded into language. And it’s really nice.

If you write on the side and you’re interested in writing, there’s no better exercise than translating. When I started getting interested in translation, I thought that it would kill my creative impetus, and now I actually think that it’s like a wind in your sails. It’s really an exciting practice, and for any writer, it’s actually almost like being in a laboratory of fiction and being able to have the microscope on how people manage to convey that magic.

BLVR: How do these different facets of yourself—the writer, the reader, the translator—mesh together? Are your experiences as a reader completely separate for you than your experiences as a translator, or do they all combine together?

ER: I feel like it’s really difficult for me to separate my reading from my translating, but when I’m writing I think a lot about rhythm, so that’s the kind of connecting thread. Actually though, it’s funny because before Me & Other Writing came out, I wrote something about Duras and Olivia and the co-translation process. Somebody read it recently, and told me that my writing actually sounded like Duras because I’d written it with her rhythm. So maybe I think everything’s very separate, but actually it’s not separate at all. I’m just not aware of the impacts. That’s probably the more true statement. My translations are influencing me in ways that I’m not even really fully aware of.

OB: A lot of subconscious stuff happens when you’re translating, yeah. You were asking whether those people are separate, and for me, I don’t think they are at all.

On a break from recording the audiobook, I was telling Martí Albert that when Will Evans from Deep Vellum sent me the tentative cover for Jean Luc Persecuted, I was shocked. I was looking at the image saying, Oh my god, this is so familiar.

The cover is this rocky landscape bathed in the blue night with this red moon, a blood moon in the corner. I had just finished filming a short film about this region that’s close to where I live in Catalonia, and the first scene is this blood moon that rises above a very similar rocky landscape. I was looking at the cover of Jean-Luc Persecuted thinking, Oh my God, that’s super weird. Why is the blood moon on my cover of Jean-Luc Persecuted?

Not long after, Emma visited me, and we went on a hike to that place and she said, you know this place really reminds me of Ramuz. And today, when I was reading the audio book, there’s this scene that Ramuz writes in a very cinematic way, in a beautiful way. Jean-Luc’s wife is openly kissing her long-time lover during a game where he’s blindfolded, and Ramuz writes about the blood moon, the red moon lifting itself up into the sky. And I was like, Wait a second!

Everything becomes a part of you. I think that’s what happens when you really catch the meaning, when it connects with you on this very deep level. It becomes a part of you and you’re sort of infused with the rhythm. I always think when you’re acting in a film or in a theater production, it’s almost like growing this other soul for the character, and then they end up living with you forever. That second soul retreats to the background, but you don’t ever stop being that character, because you’ve really lived them.

It’s the same for translation. Those authors become a part of you, their stories find a foothold deep inside you, and they come out in very different ways, some that you’re not even really aware of. So anyway, that’s a kind of metaphorical answer, but I know those people are still all living inside of me.

ER: Olivia, I could listen to you talking about translation all day. We should talk on the phone more.

OB: Yeah, we should. I miss these conversations.