“You can’t be an artist without also being an animist, right?”

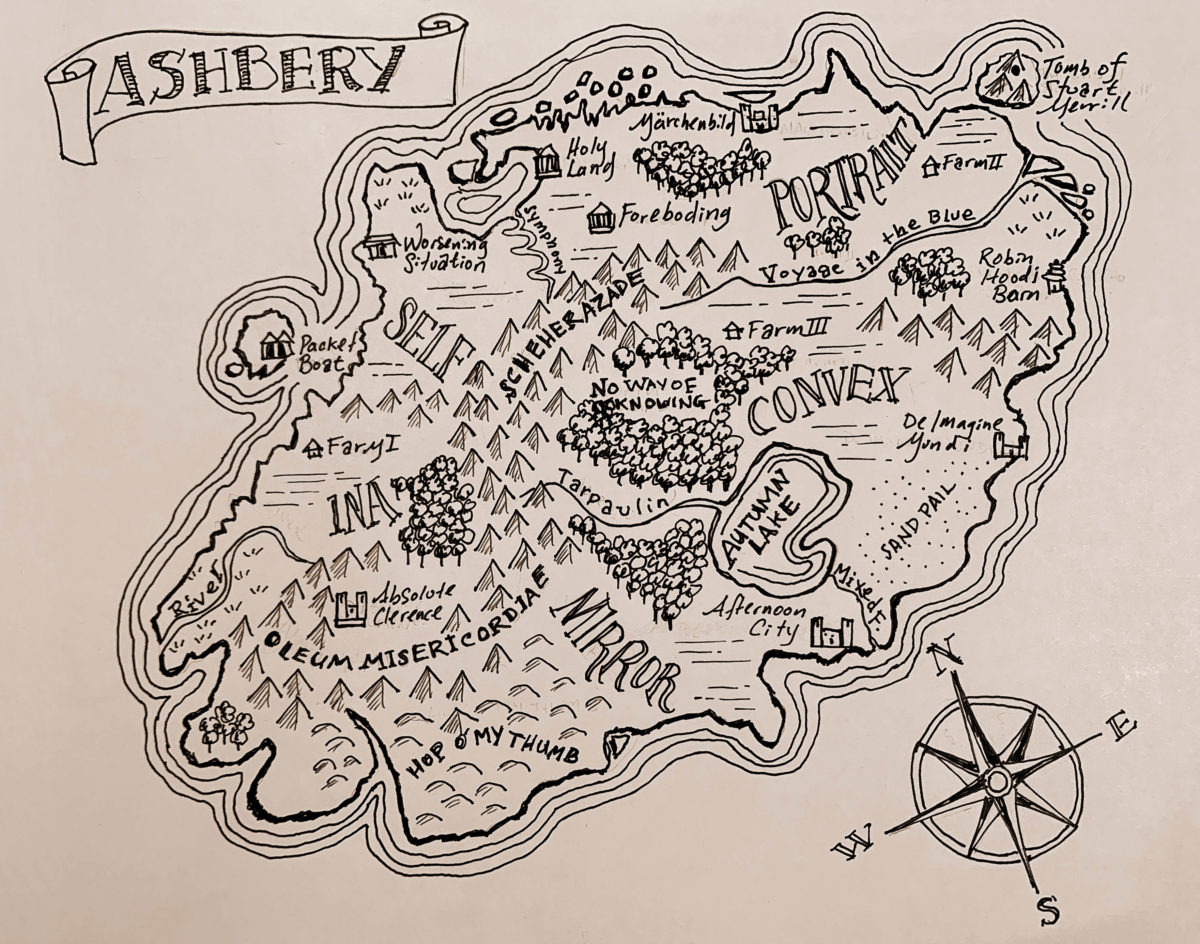

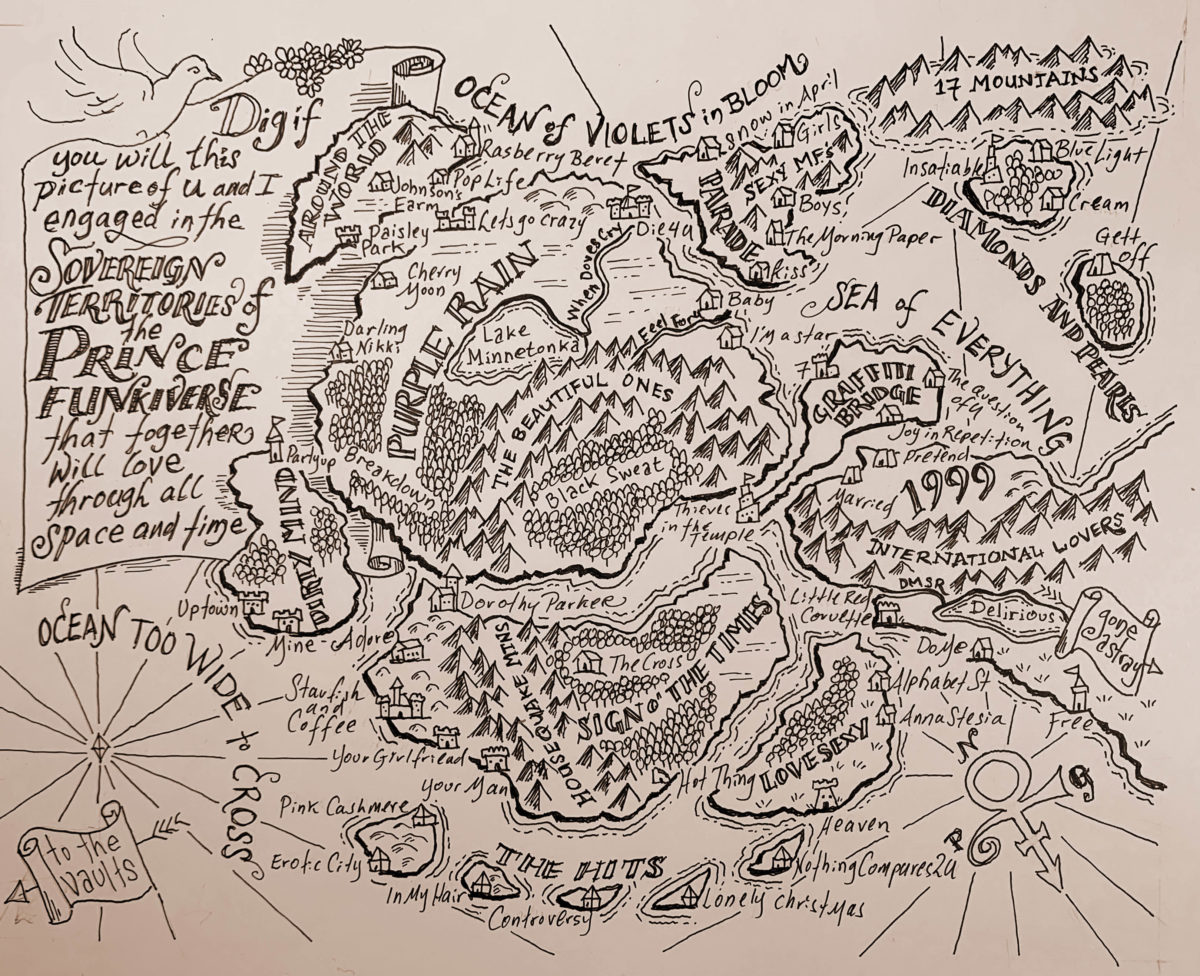

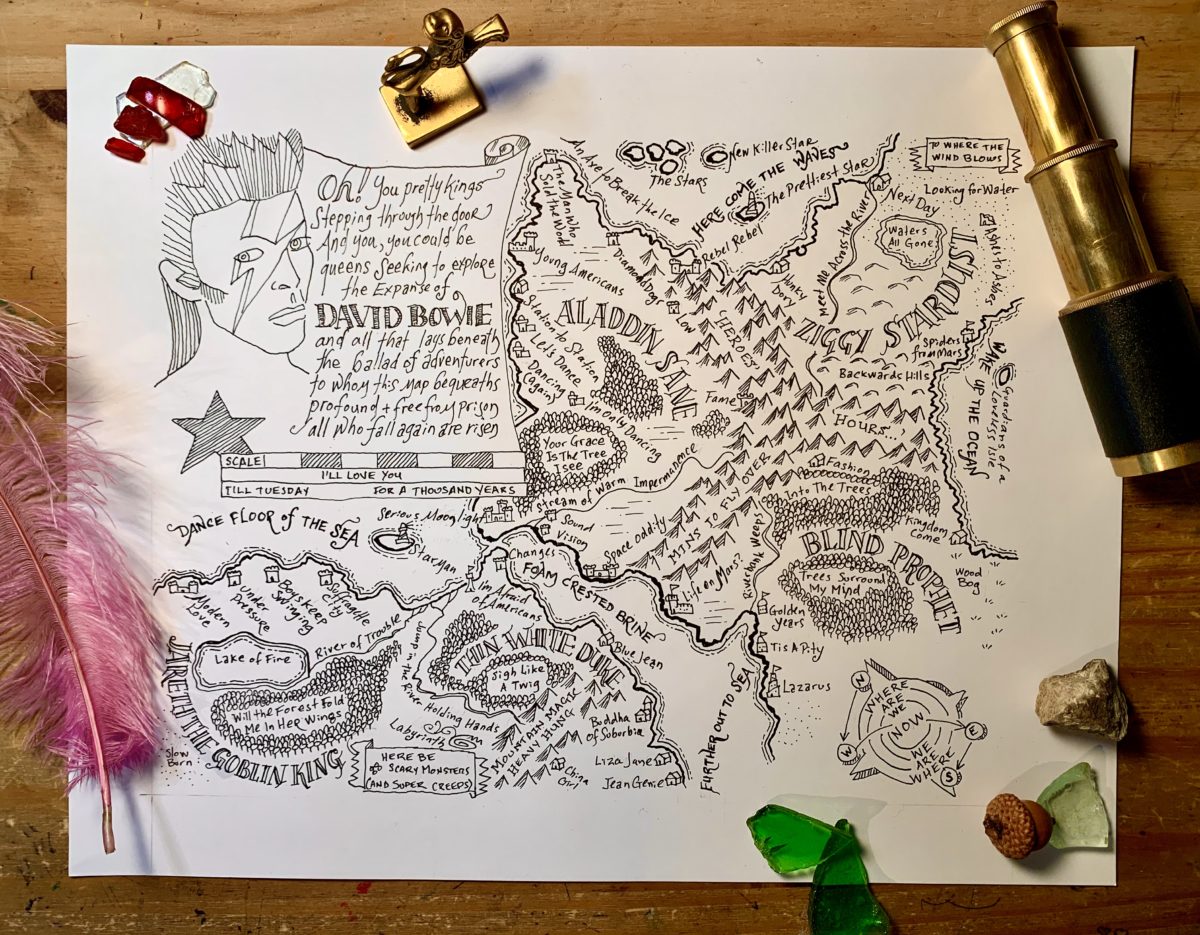

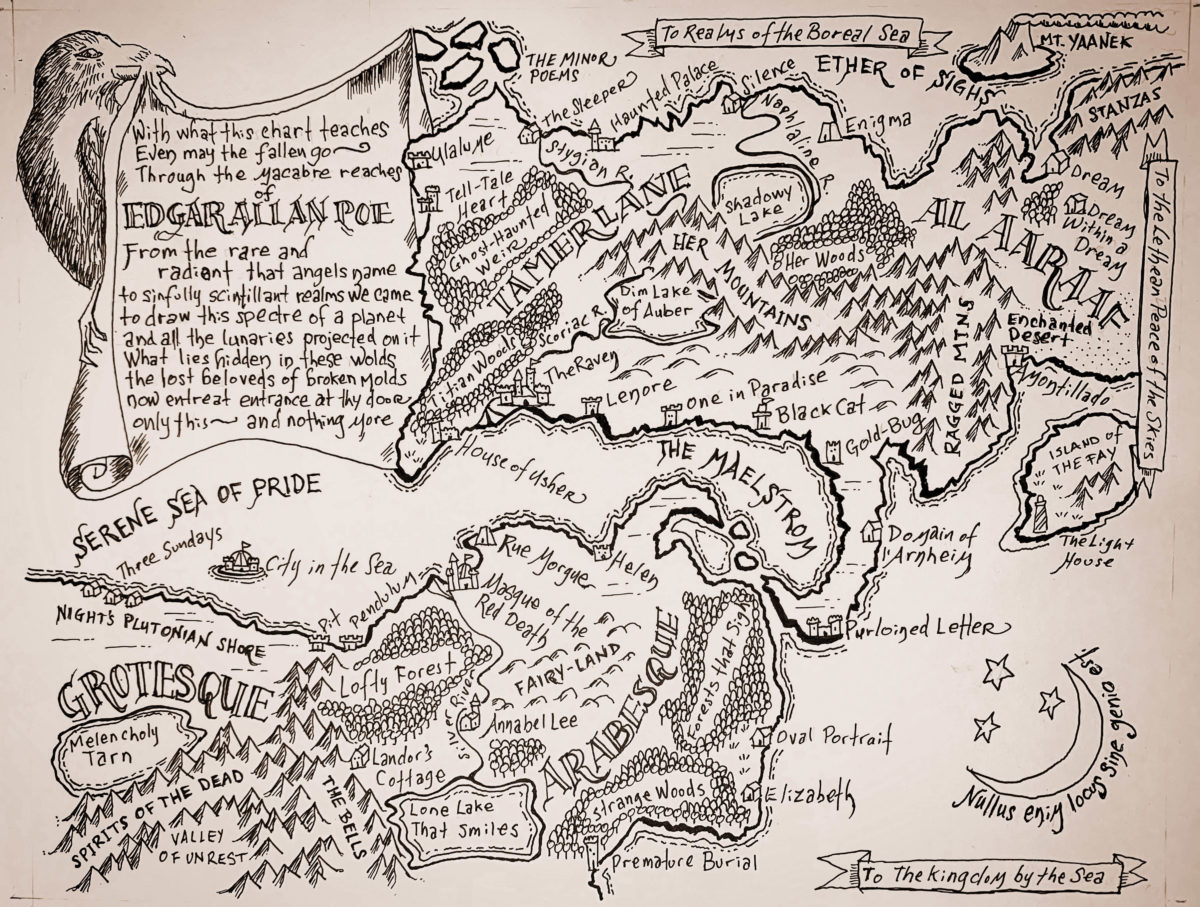

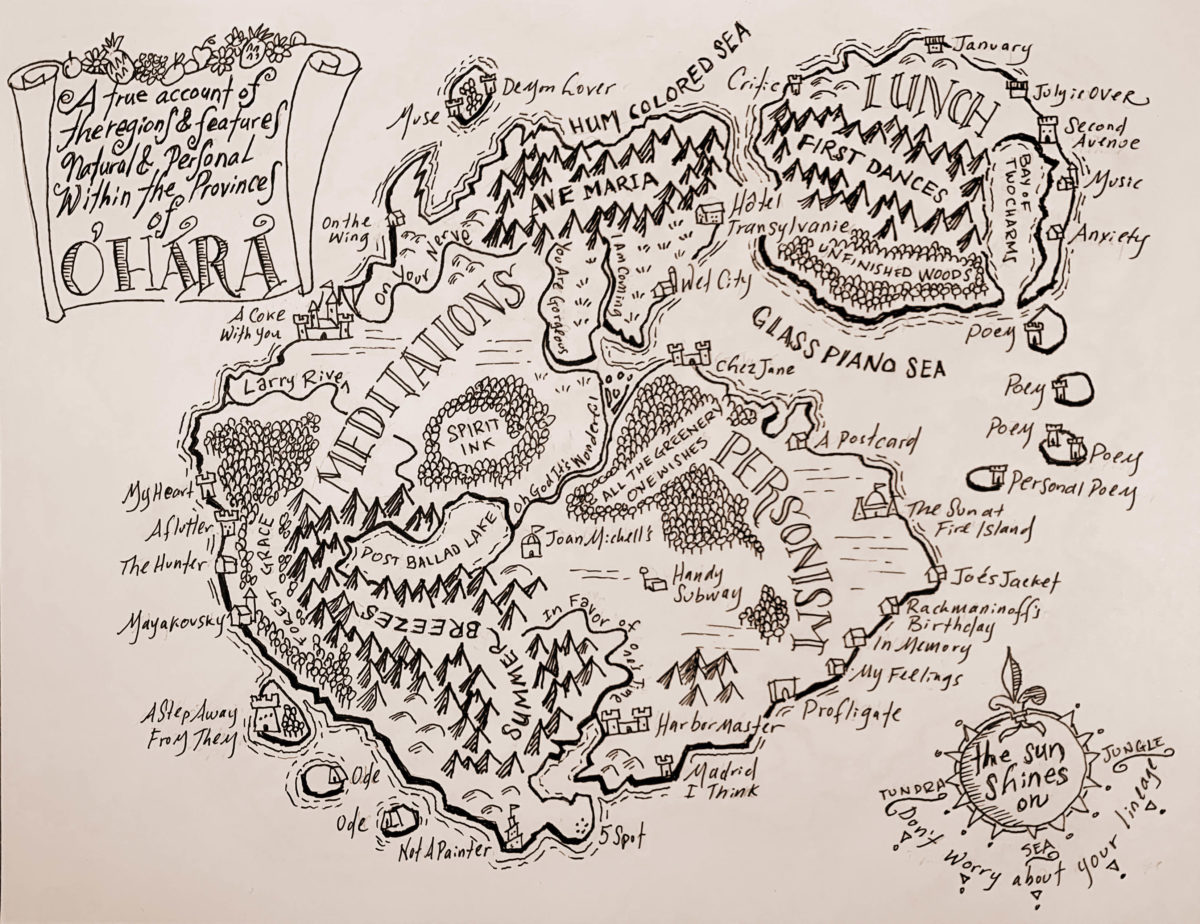

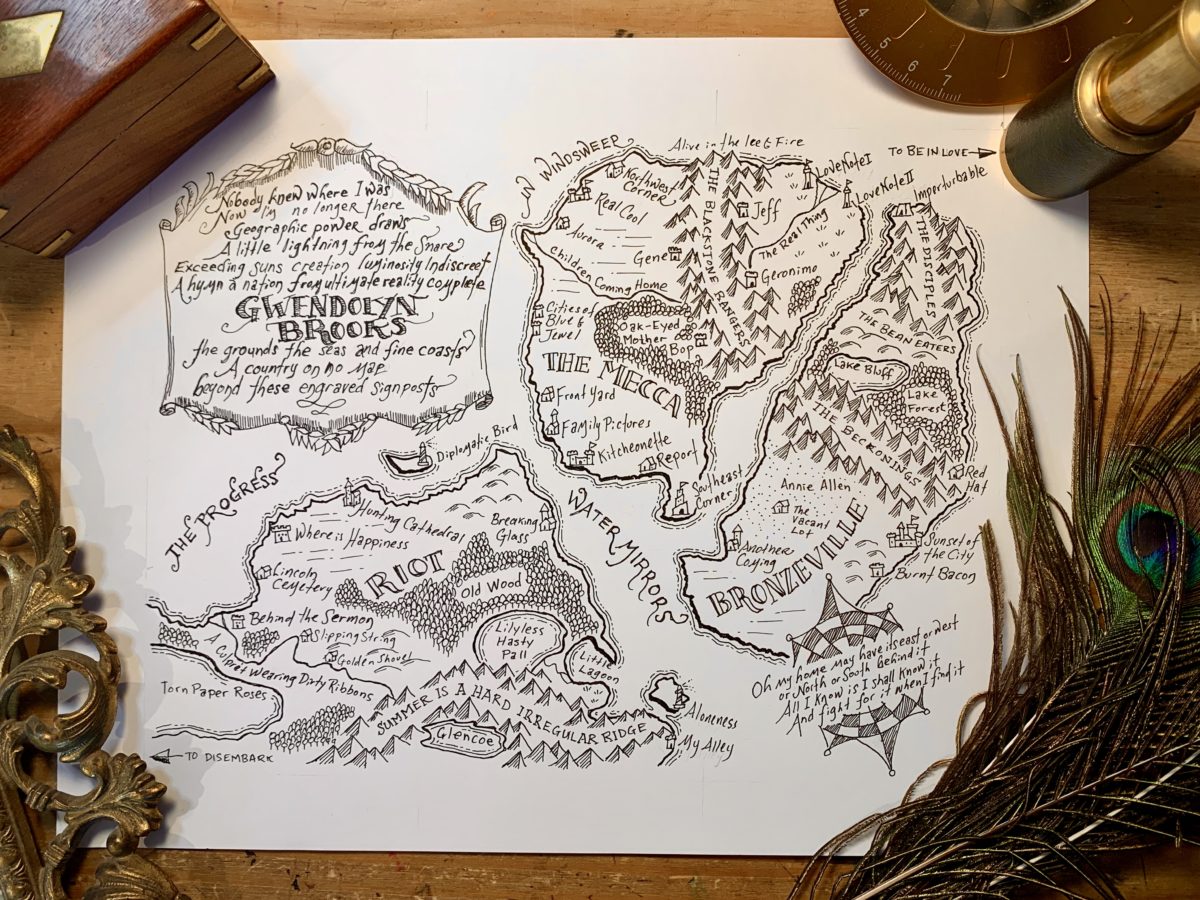

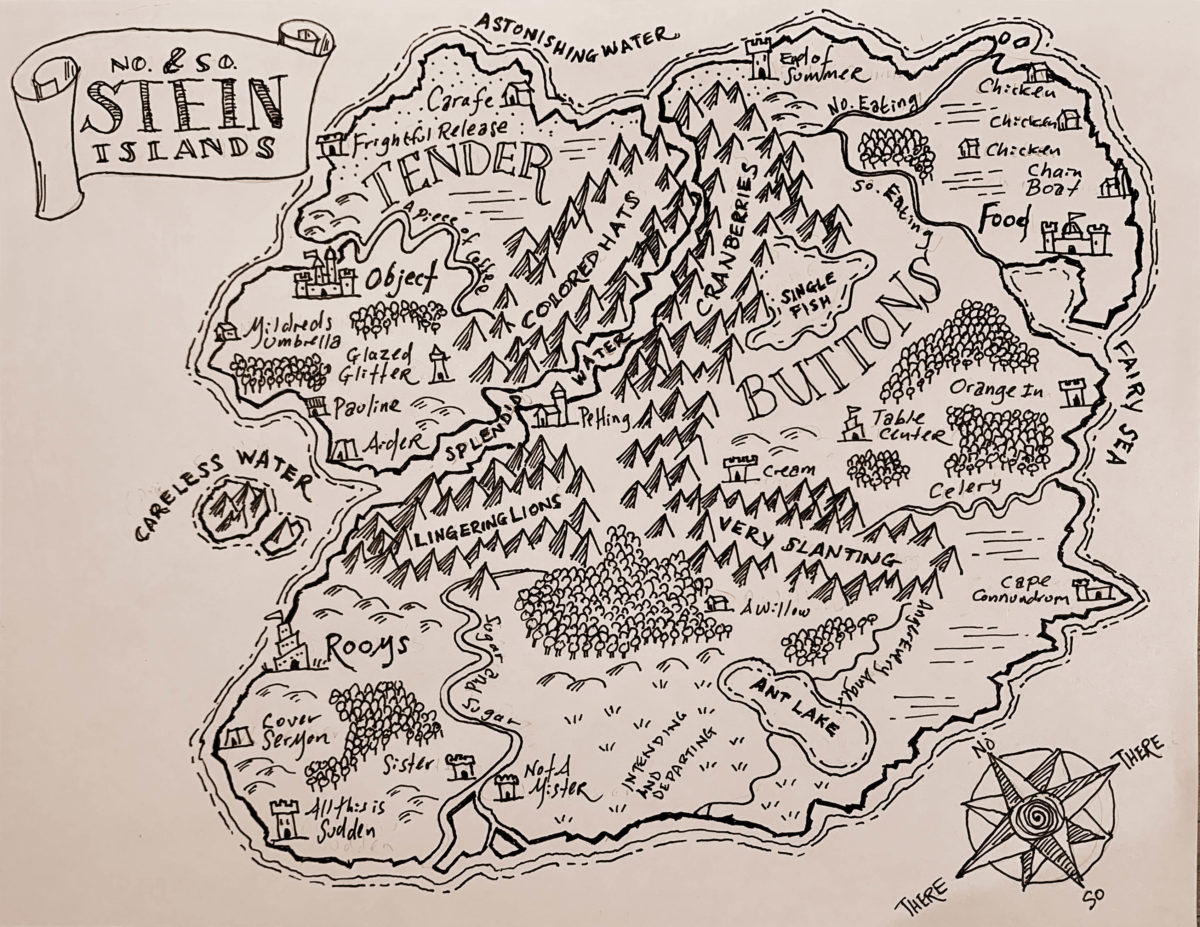

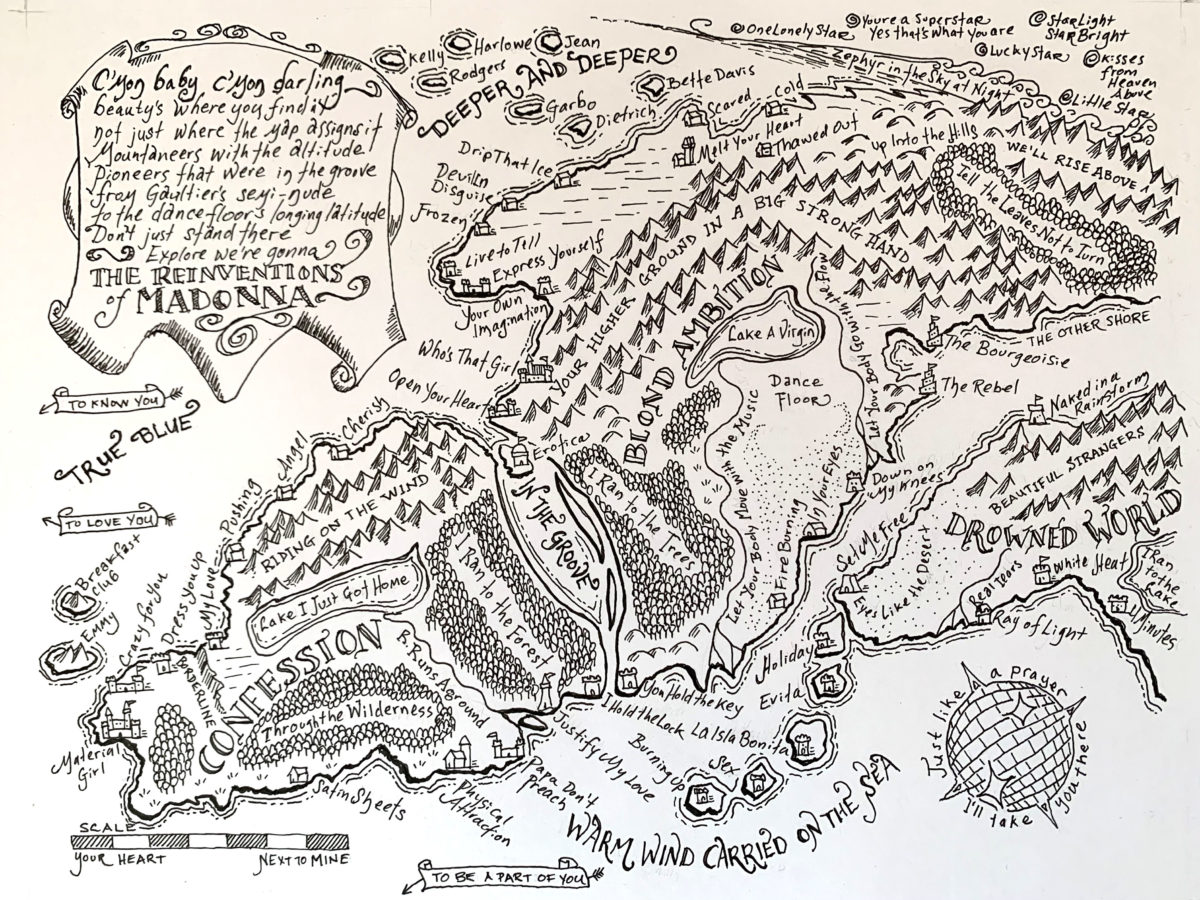

Brendan Lorber draws maps of poets and musicians’ work. Made by hand to spatialize ideas, Lorber’s maps use the visual vocabulary of Renaissance mapmaking and fantasy cartographies. They owe an equal debt to Tolkien and Al Idrisi and so far have depicted the works of David Bowie, Gwendolyn Brooks, Frank O’Hara, Prince, and Emily Dickinson, among others. For this conversation, poet Edwin Torres spoke to Lorber in further detail about his practice.

THE BELIEVER: Have you drawn all your life? That is, have you examined that part of your skill set since you were a lad?

BRENDAN LORBER: I used to get in trouble for my drawings, mainly because they were all over my homework instead of answers. But you have to understand, that geometry worksheet was crying out for contortionists in the squares and aerialists in the circles. I wrote Cirque du So Lame at the top. The teacher wrote SEE ME above that and handed it back. If I hadn’t been all awkward superego, I would’ve marched up to them and declared SEE ME is the name of my new renegade art show, thanks! Instead I meekly stayed after class and tried to remember if r=2π².

But then… when I was nine I won the art contest in Cricket magazine for my drawing of an underground city. Redemption! Later I got the best artist award at my high school graduation, which was a surprise because I hadn’t known such an award existed, and it should have gone to Rachel Egan who really knew how to paint. Or maybe to someone at Caliper, the Stuyvesant art & poetry magazine that was much too intimidating for me to go anywhere near.

BLVR: An underground city when you were nine, I bet you were constructing it since your early threes and needed time to articulate the proper tools and materials. How many invented spaces are we born with and given freedom to explore until the outside world inflicts judgement? I think there are many of those cities in existence, from every kid’s imagination. I was trying to impress Veronica Vazquez, my table-mate in third grade, but my drawings fell flat so I conjured a horsey out of my nimble little hands, to gain her interest, using performance in the guise of misplaced seduction. I failed in third grade and have discovered that the power of failed recognition is a sobering protein for transformation. School implants all sorts of experimentation, and I wonder how/if you feel your cleverness as a sage nine-year old was rewarded throughout your life?

BL: A lot of people think cleverness is a crutch used by people who don’t have feelings. But they’re wrong. My cleverness really grew legs around age five, right after I told a classmate that I was in love with her. It did not go well. By time the entire kindergarten class stopped laughing at me, I had developed a kind of pithy inner chaperone I could count on to shepherd me through subsequent moments of overwhelmingly heart-shredding heavy chop. Decades later, one glance at my face can tell you, even when I’m not having emotions, they’re having me.

Speaking of calamity, age nine is about the calamitous age when, even without the inflictions of the outside world, the imaginative world takes on a sudden precariousness. You can still play with your stuffed animals, but they don’t talk to you anymore. You become aware that you are pretending, that you are the one making them say and do things, and that your interiority is just that. Before that moment of rational epiphany, you experience your toys’ actions and voices as coming from them, not yourself. But then categories crystalize: the outside is real and the inside is imaginary. Developmental rationality, the blunt instrument by which your stuffed animals, all your lifelong childhood friends, are killed.

Making these maps, and also making poems, dissolves those categories, melts back into the original ontological fluidity. They act as a medium through which the imaginary sneaks into the real world. The real world is where other people engage a drawing or poem and be like Oh, what’s this? Before they know it, they’re receiving someone else’s ideas. And they’re casting their own ideas through the original work, which allows the work itself to conjure its own ideas, the way a spun magnet creates electricity. The work opens a liminal space in which a conversation takes place, where interiorities and exteriors cross paths. One travels with such a work from one state of being to another. That they’re maps doing the work in this case, only enhances the sense of travel.

BLVR: When I first moved to the East Village in the 80s, is when I came across the Futurists, so I drew myself a sort of parallel, as opposed to underground, map of the East Village so I wouldn’t get lost… a scenario, right there, ripe for dismantling. How we look for placement with the tools we’re given. The aerialist side drawings you mentioned remind me of Mad magazine artist, Sergio Aragones, who drew tiny scenes playing out in the margins of each issue as a running visual discourse among the satirical text…maybe something that remains for you as a hardcore NYC poet, to capture the side view while the main is in full effect?

BL: Today’s side view is tomorrow’s full frame. But in the meantime, any method that creates a little gap for two ideas to talk to each other across is good practice. Didactic work has its place and is underrated by some of the more avant guardians. Sometimes it’s useful to have an illuminated what’s what. But other times it feels better to open a chamber for the truth to light itself. And perhaps even to create a novel state in which your childhood friends, the ones who were imaginary before you knew they were imaginary, are alive and well.

When I was a teenager I made up a whole community of characters and told stories about them. It got pretty intense. At one point my mom was like you know this is make-believe right? And I quickly assured her yes, I’m not crazy! But part of me felt like I’d sold them out, by not defending them, because a part of me remained convinced there might be some portal, unguarded by the sentries of sentience, whereby the stark boundaries between inert and aminate could be suspended.

BLVR: Do you imagine a life force coming into you for world-capturing as a visual realm?

BL: Totally. But I grew up in 1970s New York so I probably arrived at the idea of animism, that everything is alive, through less than ideal circumstances. Like objects on the street spontaneously moving because of the rats inside. Or maybe one of my childhood traumas froze me at an age when stuffed animals, plants, furniture all spoke to me and were much less scary to play with than people.

But you can’t be an artist without also being an animist, right? Like nobody’s going to make something unless they can at least half believe it will have a life beyond that act of creation. Something alive definitely arrived when I began making these maps. Alive in the sense of sundara— the Sanskrit concept that beauty is located in a thing’s ability to create the circumstances for its own creation. When a work of art is really cooking, it provides the sense that it always existed, we just didn’t notice. Like a certain chord or a really good joke. They are new, and also maybe timeless. Each of my maps creates a world, but without that world’s existence there could be no map.

When a poem, painting, or strange hand-drawn map comes to life, that life emerges from a chamber where connections get summoned and endure among all the players past, present and, future. Where the artist, audience, materials, subject, theories, other artists, and their concerns, all have unfinishable business with each other. Half invocation, half invitation, half something else that they will reveal as needed, my maps allow their interrogations to draw on and feed into this vital energy. It feels good to get published or have a show, but a work of art seen by nobody is, in the animist sense, just as important. Just ask my dad whose surviving paintings mostly now live in storage. I imagine he created them out of an allegiance to the paintings themselves, the drive to nurture them, and so increase the possibilities for painting as a medium.

And this isn’t just abstract aesthetic theory. Under the sway of this force, this accountability to a living medium, I endure a kind of possession. Hours go by when I’m working on a map. Like, I’ll look up and it will be dark. Or my hand will start shaking because I haven’t eaten all day.

BLVR: John Keating writes in his letters about phenomenology, about the poet’s relationship to the object/subject being written about…and how the poet’s existence is always in question because the subject of the poem is constantly the identity of the poet, an unavoidable resolve into consciousness via language. As the poet becomes the mountain, the building, the broken heart, the political upheaval…the poet becomes the poem being written. So then, what is the poet? A lifetime of transformation awaits the language-maker, and there’s a churn out of that constant digging out from within. Out of necessity the language-maker evolves to no-language, a breath of emptiness to see what new beyond we’re going into today. So that anti-matter enters the poem’s ability for recognition…the sundara you mentioned…what a beautiful word, I didn’t know about it until you said it. How sundara is manifest in a poet’s immersion into self. The questions being asked of the poet by their poem, is a connection to your maps—how we are asked to walk language, as rooted awakenings.

BL: In making anything, the maker is the real object of transformation. Like this conversation was originally going to be about how everyone should rush out and get one of my maps. A transparent scheme to anesthetize my insecurities for a day or cajole some collectors to help me pay the rent. But I totally blew it, because in talking to you, what emerged was this idea of ontological fluidity. And then I became this guy in the grip of pragmatic grief and magical hope for the loss and return of friendship from one’s own personal pre-Cambrian realm.

BLVR: And then your mapped livingness in the hours visualized as possession, once driven by that creative trance, captures something ancient in the lines—a connection to that previousness, how art is a calling regardless of its landing spot. Working through your hungry body’s shaking to complete a drawing, or a poem for that matter, conjures the artist’s plight to remain in that focused death-light—do you have a routine or some form of discipline that nurtures your self-action, your accountability to reason for that day?

BL: I feel so much obligation to making this work. When the very good reasons not to draw or write present themselves, and there are many: parenthood and love on one hand, bills and illness on the other, I feel a kind of disloyalty to the unmade maps and poems. The artworks are there, patiently waiting in some nascent state or netherworld, and I’ve let them down.

So many people describe the satisfaction of getting out of your own way when creating art, of just doing what the poem or painting is demanding through its own inner logic. And so much of that satisfaction comes from the sense that the artwork is actually cognizant of its own potential existence and is providing you with instructions to make it so. Truth and beauty are great, but why not also animate something which so desperately wants to be alive and whose companionship predates your first human friends?

BLVR: This hidden artistry, have you been waiting for a while to unveil, or is it just that we’re in a moment of opening for you (lockdown)?

BL: When I was a teenager, I would go to poetry readings at ABC No Rio. It was in a building on Rivington Street where the bricks of the rear (load-bearing) wall had been removed. The poets would read in the (probably very dangerous) hole where the indoors disintegrated into the back yard. Too shy to read any of my own poems, I’d sit off to the side and draw the poets. Later someone convinced me the sketches were terrible and so I stopped for years, embarrassed. Not even sure where those old sketchbooks are now.

But the starkness of this past year brought to mind John Ashbery’s question “How much longer will I be able to inhabit the divine sepulcher / Of life, my great love?” Any visitor might kill you, or you them, any conversation might be the last. We had to decide who we could be around, the small cluster of hearts we could fill and who could fill ours enough to sustain us. Maybe talking that way is corniness disguised as The Profound, which is the absurd risk of all sentimentality. But crises open a gateway to the mythic that, once removed from the crisis, can read as trite.

Into the quietness of the pandemic’s new way of being came lots of books and even more music. It seemed rude to not say anything back. I began the maps out of the impulse to commune with their subjects. Only after people expressed interest in the maps did I realize they were conduits not just into the worlds created by the poets and musicians, but among like-minded admirers of their work.

BLVR: Growing up as a NYC street kid, my formative museum years were in the Bronx — though I believe I am still forming as perpetual pupae — but what sort of art did you see during middle school and high school that stayed with you? I have vivid memories of a school bus down to the UN when I was in fifth grade, where I purchased a feathery miniature of a Baltimore Oriole as a souvenir because it felt beautiful in my hands, the colors were striking, and the name of the bird sounded very exotic to this city kid. A very non-U.N. token of my experience, interesting to see what lingers in the mind from early exposure to a world outside your own. How you sometimes realize you’re different than your friends at an early age, and don’t act on that until you have language for it.

BL: Because my dad is dead I can tell this story without him going to jail. He took my sister and me to the Museum of Modern Art a lot when we were little and still very capable of rigorous magical thinking. There were maybe two security guards back then. We’d always run to the sculpture garden where we would have a brief fight about who would go first. Then Dad would hoist us both up for a ride on Picasso’s Goat. Maybe it was Marvin’s way of dominating Pablo, but more likely it was his own insouciance at play. Either way, there’s a small part of me that unconsciously thinks, if you can’t gallop through an unguarded courtyard on it, it’s not really art.

BLVR: I definitely hear you about shy kids being the ones to watch out for. I think of that sensitivity towards a visual medium, how perception guides the narrative, and the maps are there to commune with the subjects. Going on a riff, can the chance for passage be enhanced when given totems, given jewels, given a map…what are the souvenirs, the lights, transfused from a life lived that engage with our own passage through that same life…the levels of consciousness that continue to apparate the more we travel within our endless mappings?

BL: I like how you’ve parsed totems, jewels, maps as things that are given. The act of presenting makes any object totemic, a symbol that contains the real. A triple word score boon to the giver, the receiver, and to the item itself, each of whom can use their roles in the act to level up from one state of consciousness to another. Some given works describe the boundary so you can bound over (derive an ought from an is). Others neutralize it so you can just saunter through (the power of nonchalance). I needed to make these maps and it turns out, these maps needed to be made, and given.

BLVR: Can you put into language what words do as a poet compared to what images do?

BL: They are both transformative rituals of attention. William Carlos Williams said “poetry contains evidence in its structure of a world it was created to affirm.” I like the idea that poetry’s insistence comes not from what’s being described, but by what’s being enacted in the grammatical architecture and music of the piece. The same’s true of visual art, in its physical morphology. But one ritual takes place over time and the other in space.

Because it’s on the clock, poetry demands a more sustained partnership of unrelenting concentration. Language wants to hold you by the collar until the transformation happens, though you might wriggle free beforehand. The at-a-glanceitude of the visual reaches more people, but increases the odds that the viewer with be done with it before the alchemy sets itself to work. Plus visual art, through its thingliness always offers something sensual to hang onto, a sense that you get it (even if you don’t) whereas the use of language as surface, rather than transparent vehicle for meaning, often provides the uneasy sense you don’t get it (even if you do). That’s why we can get lost in a painting (good), while a poem loses us (bad).

The question is: does attentiveness capture the world, or does it create a world that would otherwise never exist? Both! The longer alertness can be sustained through a work, the more likely a new world will be generated within the audience. But to what end? Bringing us closer to what Todd Colby called “the heights of the marvelous,” or a reframing of what marvelous might be, even if it means going through darkness to get there.

The maps exist between visual and linguistic worlds and extend the ritual by moving from looking to reading and back. They owe a debt to visual artists who employ text, like Jean Michel Basquiat, Jenny Holzer, Adam Pendleton, and Erica Baum. And to poets who occupy the page in consciously visual ways, like Douglas Kearney, Rosaire Appel, Alice Notley, and Edwin Torres (wait: that’s you!).

BLVR: Yes, that I, is me… occupying the conscious page, I’ll take that! I would also counter that attentiveness is too gentle for me, the world wants to be seen, between gentility and occurrence, awareness of language as a perceptual trait speaks to intuition at the base of the retina, the back of the throat. If definition is a trap for freedom, the perceived freedom across hypertextual hybrids is to invent worlds…something you started to do by drawing your answers for homework.

A bio-morphic response that reminds me of a wonderful little book by Carlo Rovelli, “Seven Brief Lessons on Physics,” where he breaks down some basic scientific principles including quantum physics and the entanglement of binary actions, the remaining wake of the forms we leave at every transaction. To examine the disciplines at work in the settling between senses, where the travel itself is a realm to inhabit for the traveler, our invented parables root into the action of that attentiveness, and maybe allowing the senses to cross paths, transmute belonging into shift. That journey between speech and visual is always language, isn’t it, how we define what words do, as realm-makers? That phrase, “to get lost in” is an entire essay in the making, directly connected to how “found” we are told we need to be, by social standards. How many workshops are about “finding your voice.” If you find yourself, where do you go? The answer could be “beyond,” which is where poetry steps in? But isn’t art all about getting lost and staying lost? I’m honing in on something basic which I realize is not, and which I think revolves around a defiant sort of journeying among planes — to literally be given maps among invented consciousness (would the plural be consci or just conscious…how easy to be lost already) and to situate your particular perspective AS perception, maybe that’s where a giving can start to happen?

BL: All transformation is an act of generosity. Willingly passing from one state to another is an act of gratitude toward the means of transport. And the act of creating that process can only be done successfully as an entangled gift, right to the transformed, and left to the transformer. In following my maps you might arrive at a new mode of perception, and in such an arrival, you gift a new form of existence back to the map.

BLVR: How do you decide on each pair of writers/artists? When/why did you decide to bring in musicians with poets?

BL: I usually work on two maps at a time, and the pairings allow implicit connections to emerge. During the dark months among pods and cohorts, when casual hangs and chance encounters were eliminated, it felt good to create conditions for two people who wouldn’t normally occupy the same space to sit down together. I chose people whose work I love and for whom the act of creating a map is a meditative conjuring/invitation of presence. Not just to be joined by the writers or musicians, but by the people who also appreciate their work. Sometimes I receive commissions in which half the equation is already solved.

Using art as an act of appreciation is an extension of the work I’ve been doing for 30 years, in which so many of poems and drawings are communiques to or about a specific person. My first chapbook The Address Book was a collection of sonnets each titled with an address and dedicated to a person there, or to the place itself. A kind of verbal map. One of the places was 131 East 10th Street, address of the Poetry Project, where I later taught a workshop called “To Poetry / Poetry in Dedication.”

BLVR: That form of pairing connects to couplets in a poem, or grouped stanzas, a togetherness-action, pointing towards community, which brings in aspects of dialogue. I wonder about that lateral communication in the creative process, how one piece reflects another. The discipline of working on more than one painting at a time, more than one poem at a time…how remnants of each dialogue influence the process. I see the overlaying of each poem, each art piece of its time, each mapping, as a sort of code, a GPS into where now has to be for the artist.

BL: How can you not work on more than one undertaking at a time and hope any of them turn out all right? Aren’t you, reading this sentence, doing so many things right now simply by occupying your body and traversing the day? And doesn’t each task and creation derive meaning from all its secret adjacencies? Not just as it happens, but over time in the world altered by its presence? The maps have evolved through their relationship to the ones that came before and also to the personal and public events situating their moments.

BLVR: I go between holding on to the secrecy of each poem’s motivating force, or displaying that mess out in the open, in the work itself…do you find a place, in working on a direct inspiration to a circumstance or individual, where you allow yourself that privacy while displaying its motivation to the world? I always wonder about how much is too much to hold onto, and how much is what led you there to begin with, and so, worthy of exposition? The longevity of a poem is its willingness to disappear for a bit, while being read…that dynamic is endlessly fascinating to me, to transform upon each reading. And maybe that also connects to what poetry’s dedication means to you? The honor of lineage as a guide to decipher demons, is a valuable navigational tool.

BL: Every poem is a love poem, every painting act of adulation, either to a subject, or through a dedication, or to those who have worked in the traditions, or to the artwork itself and a belief in the importance of its own agency. It’s true that what you love will find its own form, and also that each form will find new ways to love.

My maps are acts of attendance to their subjects and to the people who also care for them. And they are physical things, printed by hand who’s limited number means they will become inaccessible after a sometimes very short span.

Here are a few hidden facts about a new sonnet sequence I’m working on at the same time as the maps. They’re fourteen lines long, each line about the length of one of Ginsburg’s American Sentences. Each with a caesura that’s totally Beowulf, Descent of Allette, Asphodel, That Greeny Flower or an old carburetor, depending on the tradition you’ve got in mind. They try to move so much, as Frank O’Hara said to Vincent Warrant “it is hard to believe when I’m with you that there can be anything as still / as solemn as unpleasantly definitive as statuary when right in front of it / in the warm New York 4 o’clock light we are drifting back and forth / between each other like a tree breathing through its spectacles.”

BLVR: When traveling between each set of maps, where do you choose to let yourself land on the writing that appears in the maps? How does the text make itself clear to you?

BL: I drew the first maps, of Gertrude Stein and John Ashbery, as a way of having them as guests in my home, and to begin a conversation. The tender button pushing of Stein’s work for example, lends itself to geographic rendition. Ashbery’s remarkable remark-extending practice has a tectonic quality that reveals stable landscapes as actually protean and genetic (in the genesis sense) that can’t help but create new landscapes. Certain geographic features, like naming several towns Poem on the Frank O’Hara map, seemed to call out to be drawn.

BLVR: Having invented-guests in your home during lockdown, is to create the conversation that can only happen metaphysically. If I lived in the town of Poem, I would wonder about the locals. Maybe to have a winter home there, and live in the realm of Dickinson, near Syllable-less Sea, is to have a pact with some invented deity. I guarantee a scholar of each map’s namesake, would uncover branched opportunities within palimpsest of each pairing’s topography—let’s do a quick rundown here of the protean landscapes; John Ashbery & Gertrude Stein, Frank O’Hara & Prince, Emily Dickinson & Edgar Allan Poe, Gwendolyn Brooks & David Bowie, Robert Burns & Madonna—cultural touchpoints intersecting as canon.

BL: These terraforming conversations are happening right now! Can you hear them?

BLVR: Each one as connected as they aren’t, true songs enlisted by the author; you. Your vision is the voicing of each artifact, so the question of how you decide each pairing is as much your performance as our ears/eyes’ curation. I wonder here about the empowerment for an audience to invent? Part of any artistic journey is the understanding that you are under the guide of the artist, the person offering an expanse for imagination.

BL: One person’s imagined scene is a revery, but once that revery expands into an environment for other people to walk through, it generates a reality of its own. Or several realities, generated as sparks leap across the gaps between the artist and what they’ve made, the artwork and the audience, between their expectations and experience, between what the artwork is and what it becomes. New apertures form in the spaces traced by the sparks, which in turn generate more sparks.

BLVR: How does territory enter your choice for landmark?

BL: Looking at the maps you notice the features, but the maps are mostly just the space between features. And that feels comfortable because it mirrors our own consciousness. Consciousness being the active blankness. And blankness is where the real action is, fed by constant incursion and our own spontaneous excursions. We live as the locus of a mostly invisible space that our attention occasionally lights up the walls of, or someone else sends a beam in through the windows. I chose landmarks in relation to one another, the way we make that light happen, holding two ideas close enough for a spark to leap over the void and so a new, third thing, suddenly exists! You are the catalyst, looking at the maps or at anything really, who creates something from the relationship of a line and your desire, or of a musical note and your anticipations. A lighthouse needs the fog to be a lighthouse. We all need our relationships to be whatever it is we’re in the process of becoming here in the created/creative realm.

BLVR: The thing’ing of one’s circumstance becomes the relationship needed in its time. Can we activate a blankness as a territorial marker for continuation? Sort of what you’re proposing, that the audience receiving your dense blankness as the bounce-pad off your scrum, is the one who decides the landmark? It’s interesting to be discussing emptiness and invisibility among artworks so rich with visibility, I wonder about that tectonic untold friction among the layers, the human and bio-morphic layers of our beaming, what do you think of allowance and humankind’s ability for inner-beaming, as it were, to achieve some new interior relationship to landmark as life mark? That’s a loaded query…feel free to alter your response out of whatever you make of these interstitial avalanches.

BL: I wonder what we look like to the landscapes we move across. When you walk past your now-inaccessible childhood home, does it remember you? And if your old key still worked, could you walk upstairs and allow the environment to awaken the state beyond inner/outer. Perhaps there are other entrances that we developed and then forgot the ability to find. Perhaps anything is a potential entrance, not just Proustian madeleines but unfamiliar objects, food, rooms. Anything could be the cauldron for the potion or lyric for the spell.

BLVR: Every map is an island, what ocean are they all existing in, and is there a historical chronology for our getting lost?

BL: Maps are fortune-tellers. If they’re maps of real places, like those of Muhammad Al Idrisi, Fra Mauro, or Gerardus Mercator, they reveal what a traveler will encounter before they get there. If they are fictional, like Tolkien’s, they foreshadow the story’s arc. They always exist in conversation with travelers, inciting them to head out, and guiding them on their way. A vacation invocation.

My maps’ organizational principles also accrete around how we receive the writers and musicians. Landmasses develop around major works, as with Burns, or changing identities, as with Bowie. Early pieces were self-contained, charted as islands surrounded by water. Later the territories extended beyond the boundaries of the map itself. The logic which drives each piece is loose enough to permit exploration within the exploration.

It might be an interesting, ambitious project to create a mappa mundi in which all my maps fit together. To the degree you’re aware of the subjects, all these maps already exist in your own shared universe. Why shouldn’t there be three weeks’ journey over land from Gwendolyn Brooks to Edgar Allen Poe and then another seaborne month to the shores of Emily Dickinson?

BLVR: Now you’re bringing logic into latitude, longitude and lengua-tude… that’s our job as traveling human islands, isn’t it? As land masses gather in your maps, according to their given language, and push out new finger-lets around accumulated friction points, the identities of each terrain reflect each given hardship, each earth’ed geo-layer renamed in its native tongue. The world map is here, you’ve opened the ports of sail and more are waiting. Though you could say it’s already arrived for each of us, at birth.

BL: Maps are prologues to future discovery, but they’re also a record of the past’s lingering effects. Just like our own bodies, changing and being changed. A clock with infinite hands, ticking in the palm of our hand at the end of the mind.

BLVR: Do you think the world has feeling for us? Rather, how would you listen to a world that wants to travel over us?

BL: Definitely. Maybe all our scramblings over the surface are how it speaks, expressing those feelings. We’re too tiny and specific to hear it all. But by traveling we can catch a whisper. If something as rudimentary as a person has somehow developed consciousness, how could an entity as big as Earth not have a larger consciousness made up of everything and which lends sentience and animation to even a lost jacket button or mossy rock? I could be wrong, but its more interesting if I’m not, right? To wake up alive on a planet with plans for us.

BLVR: As far as extending the territories beyond the map, that’s what happens in many creative processes, as you embrace the journey you’ve undertaken—to exist the journey makes it so, sundara. Using the page as topographic entrail, I think of how space both invites and obscures sensorial geology. Where can new meanings for perception exist but within dimensions of the experiential, and how to portray that movement on a 2D surface?

I think of the incredible Proun drawings by the revolutionary Constructivist designer El Lissitsky, defying space with impossible structures…or Renee Gladman’s incredible Prose Architecture drawings, which question form as lived-in speech. Both those examples have a different density than your maps, but there’s a shared charting in the logic.

BL: I like El Lissitsky’s Proun. Proun was a Russian acronym for Project for the Affirmation of the New and he was very optimistic about the political reshaping that he hoped the revolution would make possible (sad trombone) but it definitely applies, as do Gladman’s prose architecture drawings for people to occupy impossible spaces. Impossible because people are impossible (not in the curmudgeonly sense, but also yes that) but in the sense, how can consciousness inhabit these soggy meat shapes?

BLVR: The combination of imagination and technical achievement is really powerful…can you talk about line width, about that steadiness over a course of topography…a sort of metaphor for a clarity of thought across wild terrain of poetry/history/life…talk about texture achieved by grouping same line width together?

BL: Repetition and visual affinity are pretty powerful. But can I talk about fear? The fear of mistakes while working ink over paper. The further into a map you go, the higher the stakes. One false move can be world wrecking. And before that is the fear that an early guiding concept is flawed enough to throw everything radically off course later, when it counts. (That fear exists even now in answering these questions!) Those apprehensions are the real storm-tossed here-be-dragons that hover at the periphery.

Having said that, each map builds on the techniques of the last. More complex mountain ranges, more detailed approaches to the shore, a wider breadth of topographies and icons. There are through lines within each map and larger harmonies from one to the next. The jagged ranges of David Bowies’ Mountains to Fly Over and the others in Gwendolyn Brooks’ Summer is a Hard Irregular Ridge, are they two different sets of mountains, or are they the same ones twice?

BLVR: The density of that visual texture is a reference to the depth of the language for each landscape, each map’s visual terrain is a literal terrain. And how we can physicalize metaphor. This gets into the visceral experience of holding a printed piece, the snap in that paper stock, running fingers across those subtle impressions — you know, how we groove on the touch of something handmade. That’s the old Type Director in me talking, how letterpress leaves a reciprocal conversation on your fingers.

BL: The fact you are holding this thing that I once held, is it erotic? Perhaps. But more umbilical. We are all physically connected over time to some original organism. And part of the satisfying nature of an artwork’s physicality is that it echoes that. What makes going to a museum so frustrating, and why they now have guards and ropes, is that you’re not allowed to do the thing we all want to do: touch the paintings. In touching, you become physically connected to the piece and its maker, and to the lineage and traditions beyond. From the same pre-historic node in our brains that makes the post-pandemic return to giving friends a hug so cathartic. A lot of people who have obtained these maps put them in frames, but before they do, they get to hold it directly and have the tactile voyage over its pleasing letterpress ridges.

BLVR: The first maps are simpler, the later maps get denser…the reverse of Neruda’s later odes being minimalized from his earlier dense language. How far do you get into complexity as you dive into the process?

BL: Given how much I like the subjects, the seduction is to keep going… but then we’d end up with something like what Stephen Wright once said “I have a map of the United States. Actual size. It says, One mile = one mile.”

Regardless of their elaborations, it’s my hope that, you’ll lose yourself among all that is to be found in these maps, and that these maps of consciousness might find in you something you’d never noticed before.

BLVR: The last Madonna map has added @ locations…is there a social media map on the way?

BL: Ah! Those aren’t at glyphs, they’re celestial swirls, a la Van Gogh’s Starry Night, indicating locations of Lucky Star, etc. But beyond the cosmology of all social media, you’re a superstar yes that’s what you are.

BLVR: Yes, and how an island called Eroticas is in a channel called In The Groove, which then lets us navigate a boat we can call Strike A Pose! But touching on social media, I think these maps connect to a search before internet, a literal GPS for identity, using signifiers from each person’s past lives as language landscapes that might present parallel lives to our own. Walking meditations spurred on by the possibility of an imagined journey, can transpose a void for a lasting impression. Whereas glass on a screen is a smooth swipe, and how this generation is growing up with that smoothness, so…where does visceral reality ignite depth?

BL: I like my phone’s GPS. I’ve got anxiety about so many things, it’s a relief that getting lost is no longer one of them. But there’s something that can only be gained through a paper map, perhaps marked up with your own notes as you go. They add a layer of intrigue, never being 100% sure you’ve successfully located yourself on it, or that you’re headed in the right direction, and a sense of achievement when you get where you were going. And of course there’s the thingliness of it. I have so many old, badly-folded maps from a time before Google Earth. When the pandemic began and I was stuck at home, I got out those maps to visualize a time when we might be able to travel again.

BLVR: Observation not a question: I think of Tolkein’s maps drawn on the inside covers of his novels… how that always gave me an added impetus for literally, going into, the story. A sort of treat for the reader, to situate themselves for all the storytelling to happen in. Also, an equation to a modern mapping of a body’s travel, to achieve destruction or to mark a passage.

Feels like the selecting of lines for each poem, is like finding runes for the reader, life forces from each artist, to point towards like-minded paths (for the reader)…which you’ve devined as intermediary/interloper between realms.

BL: Yes! I’m happy that you’ve honed in on the runic as intermediary echoes of a life force. Maps are artifacts left behind by those who have come before, not unlike stone-carved emblems, guiding us towards what’s next. Even the stars are navigation beacons whose distant light only now reaches us from bygone centuries, but who’s positions lead us to what hasn’t happened yet. Google translates the Arabic name of Al Idrisi’s big map as “The excursion of one who yearns to penetrate the horizons.” In every case the mapmaker transmits from over the yesterday’s horizon, linking present day travelers to tomorrow.

Cartographer and scientific polymath Alexander von Humboldt recognized the world around him as fluid, defined in terms of relationships which themselves were always changing. I only learned about him when Adam DeGraff took a break from being an amazing poet and dad to send me a link to Benita Raphan’s short film Up To Astonishment. In it, Susan Howe and Marta Werner discuss Emily Dickinson, but also maps. Dr. Werner says “a good map… plumbs the depth, the texture, the tension, the resonance in the moment of its execution.”

BLVR: The other sides that call for you — don’t know why that reminds me of R. Crumb’s “Fritz The Cat”…maybe the think-thin lines evoke his crosshatched brushwork for some slickity cat-ness, imagining folklore, deep as an x-rated kitty, smoking grass with Gertrude Stein.

As far as, “resonance of tension,” is that where we, as artist humans, can truly stretch out? The fluidity of our world, as precursor to witness, creates a constantly transforming horizon. Bringing to question how translation interprets what we’re ready for, and how we align translation to habitation, whether by language or neighborhood. Speaking of, I’m brought to our sightings of each other, in the East Village 90’s, our home buildings, side by side. I almost always saw you sitting on your window, just above the steps, taking in what 4th street had to offer back then, as I made my way to my studio apartment, at all hours. Our baroque impressions of an East Village in transition, that delicious sort of tension between the planes of urban upheaval, feels like an excursion to unravel memory out of…very map-py, no?

BL: Mappy, yes! I wonder if part of downtown’s historic allure (now long vanquished) had something to do with its deranged street layout. Above 14th street is a traditional grid, below an insanity of crosshatched brushwork. A geographic translation of its residents’ freewheeling sense of direction. I think I lived on the corner of one street based on where a family of deer thought it’d be good to head in 1630, and an avenue that paralleled a crooked stream that dried up 100 years ago. All those foundational interruptions that replace destination with being destined to run into someone on every journey.

BLVR: How far have you traveled?

BL: Not far enough. I’ve lived in New York City my whole life and sometimes it’s hard to see behind all the labels my memories have covered it in. But I hope I’ve travelled emotionally, and become a more generous, less fearful person over the years. And I also hope that, now that our usual habits, motives and, methods for movement and action are so disrupted, these maps offer new techniques for travel and adventure.

BLVR: What does distance mean to you?

BL: The biggest distance that can exist is between people. I learned from my dad that art can collapse that distance. He was very quiet and very old when I was growing up, and he spent a lot of his time doing weird things. Like sitting on a fire hydrant with a sketchbook, drawing every brick on a building across the street. Or going to the beach and facing away from the water so he could draw the way the dune grass moved. Sometimes he would take my sister and me to Rocco’s on Bleecker Street for Italian Ices, but just as often he would take us up to the Chelsea Hotel to look at the new paintings in the lobby and staircase. It was hard to connect with him directly, but showing him some new drawing I made, or flipping through his sketchbooks made me feel just about as close as two people could be. After he died I inherited his sketchbooks, including much older ones with drawings of his first wife and the kids he’d had before. I’d never seen those drawings when he was alive. He never talked about them and I felt very sad that that gulf existed in his later life.

My dad was a student of Hans Hofmann, who he admired, but he disliked the New York art scene and rarely showed his work. It was only recently, long after my dad’s death, that I discovered so many of iconoclastic artists I was drawn to like Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, and Larry Rivers, were also students of Hofmann’s. I wonder if my dad had been friends with them.

BLVR: How wonderful to have that creative connection with your dad, to know where your sensitivity for the seeing world comes from is so vital. I have fuzzy memories of my father enjoying the sensorial aspects of his life. He died when I was ten, I’ve written plenty about him, but since my boy was born, more has emerged, trying to get into his head as I figure out mine. Funny how that happens, the conversation around common ground, collapsing a distance, as you say. It’s interesting to have discovered your dad’s hidden drawings after he left, he may have wanted to hold onto a part of himself, what parents do to sense protection for their kids. As a father yourself, how do you approach the idea of secrets to your daughter? Is there a way you can explain or share what a private place means to your child that might empower her imagination? My boy has, by now as a teenager, experienced my own hidden surprises as I model them in my poetry, I suppose showing human complexity as a rite of living…so I’m wondering, as we go off into the requisite dad part of our conversation, about our ancestral mapping as it were (see what I did there)…those memories of the undefined ‘weird’ leave an imprint, and I wonder if we attempt to access that in our creative output as continual reinvention, or as possibility for some sort of deepening?

BL: There are heirlooms we don’t know are heirlooms. They’re just objects or genetic tics that exist in the present, but are secretly charging themselves right now so that they will always be portals back to this moment. My dad died decades before my daughter ever got to meet him, but I have his paintings on my walls. Aurora sees them every day and knows I have a strong attachment to them. But to her they’re probably pretty inert. She’s watched me make these maps though. She knows they’ve been paying the rent during a time when money’s been really tight. She also knows the joy surrounding their making and giving them to people. I think she’ll look back on this time with a story. Maybe not as good as my dad letting me ride the Picasso, but at least there’s something. And underneath that, she’s forming a connection to the maps that maybe allows her to understand the connection I have to my dad’s painting.

BLVR: Where do we start and go to?

BL: I’m probably misremembering but I think Paul Bowles said he hoped he would die as far from his birthplace as possible. It seems like something he would say anyway. Douglas Adams had his characters experience the opposite of that in Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy; the further you are from your home the deeper your despair at facing death. In my experience, the displacement has more to do with time. The low-rent neighborhood of my childhood was billionaired out of existence. I have a scar on my chin from a bicycle accident on an abandoned highway that was torn down a long time ago. Another scar on my cheek from the stoop in front of what’s no longer my home. The world I was born into doesn’t exist. These maps are a way of charting another world that, for its timelessness, is navigable.

BLVR: The world is indeed in constant re-existing, an astute position for linearity as existence. Which leads me to two final questions. Is this an ongoing project, it seems it would depend on your own fortitude, time, and ink…but the possibility for a billion pairings and crossovers seems endless? And then finally, what is it about a journey that speaks to you?

BL: It took awhile to realize that the real journeys are the one where the changing geography changes the traveler. Maybe because that’s such an obvious thing. The handful of trips I return to in my mind are the ones that totally gang aft agley. Like the seventy-two hours I spent in Edinburgh when I was nineteen, without sleep or a place to stay, chased by cops, a group of guys from Chicago, and a murderous Glaswegian who mistook me for someone else. Or the twenty-six hours aboard a ship in the North Atlantic during the worst winter storm in decades that felt a little like an ocean-going reboot of The Shining. Or the time in a medieval Italian city where I thought the P sign meant Parking not Pedestrians Only and I managed to hopelessly wedge our Fiat into an alleyway. (Some locals who’d been watching the fiasco later helped turn the car sideways and lift it out.) Or the Romani people who took me in when I found myself on the Charles Bridge in Prague in the middle of the night (again with no place to stay. I was 24 then and should have known better.) I’ve had fewer of these transformations more recently thanks to better planning, etc. But physical travel is the conceit, the MacGuffin, the objet petit á, that can get the changes underway. And for now, stuck as we all are at home, a map is a good way to elicit the feeling of travel, and the possibility of travel’s inner makeover.