I met Rosie Stockton at a party Rachel Rabbit White held, called Porn Carnival: Los Angeles. Rosie’s poems are a treasure chest of poetic forms, with language both proper and rowdy. They’re an Edna St. Vincent Millay of our Gender-Fluid generation. When I saw an announcement for their new book Permanent Volta (published by Nightboat Books), I eagerly arranged this interview.

—Ben Fama

THE BELIEVER: I’m really into Permanent Volta as a title, since I read it as a paradox: if a turn or pivot becomes permanent it then exists as motion.

ROSIE STOCKTON: The contradiction posed in the title is one of the main questions I was writing through in this book. As you say, if the turn is “permanent,” it exists in motion, in a constant state of becoming. I was interested in constant becoming in relation to form. Usually sonnets only have one volta, followed by some semblance of resolution in the couplet. How could a “permanent volta” refuse this resolution? I might even distill this poetic question into a familiar political question around reform or revolution: what does change look like within a given structure vs. what does it look like to change that structure? Like so many poets since the 13th century, I took the sonnet as the structure I wanted to sabotage, slow down, hustle, edge, and flood as a way to ask this question.

If the volta of the sonnet allows for the speaker to “turn” from one movement of thought to another, I wondered what tactics I might use to both perform change within the sonnet’s system and also dismantle the structure of the sonnet itself. In this way, I was interested in the historical material processes that gave the sonnet its authority. Who authored, and authorized, the first sonnet?

It turns out that the sonnet was invented by an Italian royal court lawyer in the 13th century named Giacomo da Lentini. He created it by taking a Sicilian peasant folksong of eight lines and adding a volta, followed by a inward turning, contemplative, sestet. The first octave sets up a feeling or question—oftentimes unrequited love—and then the turn moves toward the solution found in the final sestet. Sonnet scholars argue that the volta of the Italian sonnet marks the dawn of Humanism—that era where the solitary thinking “I” in all its individuality began to represent the height of meditative transcendence and the production of a harmonious soul. The volta initiated a literal turn away from the a musical form of the commons toward a silent, lyrical, individual meditation in the final sonnet form. I imagine this royal lawyer guy appropriating the strambrotto form in this literary moment of expropriative violence to help forge the modern subject and its experience of desire & fantasy as we know it: a rational, inward facing, sovereign—literally royal—self.

The idea of permanent volta is sort of a problem for metaphysical thought, anticapitalist struggle, and romantic love—can an incessant turning be a mode of escaping the inward, the individual? Can an incessant turn undermine the stately, romantic love required by the sonnet? How can the constant turning produce something in excess of the structure that enables it?

BLVR: That’s really fascinating, I’m really interested in the eight-line peasant song (I do love a tune) but I wanted to ask perhaps a more pertinent question. In terms of metaphysics, I tend to like philosophical problems more than their solutions, so this “something in excess”… what is it?

RS: Metaphysics—or the question of being and nonbeing—has major stakes for how we conceive of and resist political subjection. I think a lot about this formulation by the Greek philosopher Heraclitus that has now become a cliché: you can’t step in the same river twice, because the waters are always changing. But he meant it in this way that illuminated how the structure of the river—the river bed—exists in relation to the water that moves through it. Constant transformation to Heraclitus actually maintains a larger stasis. Being is becoming, as he puts it. In the context of this project, I was interested in how water might change the structure of the riverbed. Can water go on strike? At the time of writing I was living in a house by a river that was constantly flooding my yard, so this philosophical question was also very material, in ways that related to the climate crisis, a failed city infrastructure, my own failure to contain the water with ditches or sandbags.

The phrase “Permanent Volta” is also a play on Marxist theories of permanent revolution and mass strikes. In “The Mass Strike,” Rosa Luxemburg describes the movement of mass strikes using water imagery that is “ceaselessly moving.” She writes the mass strike “flows now like a broad billow over the whole kingdom, and now divides into a gigantic network of narrow streams; now it bubbles forth from under the ground like a fresh spring and now is completely lost under the earth.” This is also how I picture life in excess of subjection to violent political or poetic forms: moving like water.

To me what is in excess in the most basic sense is life that persists despite and beyond political subjection and flows of desire & practices of care captured by the couple form. Love is excess when we can engage it as a communal practice and feeling, rather than an efficient or alienating one. The mode of love-as-excess I was compelled to explore in these sonnets were personal, and circled around queerness, pleasure, kink, gender deviance, and anti-work politics.

BLVR: Regarding that last bit: “queerness, pleasure, kink…” you have a lot of juicy lines: “dildonic my massacre / a neo-gloryhole’d liberal fantasy.” I wanted to ask who in literature and art inspired you to aestheticize kink?

RS: This poem is a loose associative “translation” of an Arthur Rimbaud poem called “Tale” which came out of thinking with Kathy Acker’s book In Memoriam to Identity, where she rewrites the doomed love affair between Verlaine and Rimbaud in this very unhinged and steamy way that also makes liberal subjectivity look like a joke.

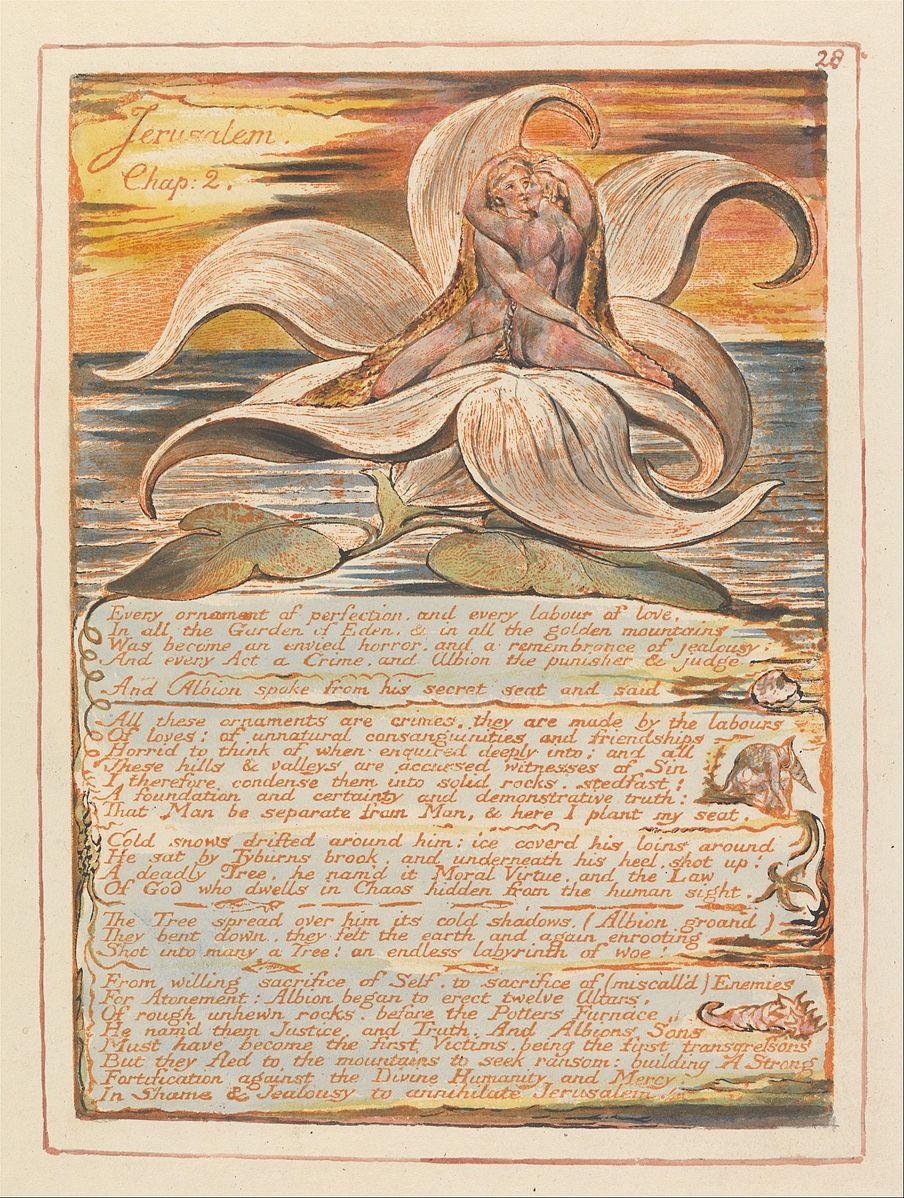

But regarding the revolutionary potential of kink, my first instinct is to say William Blake: he was obsessed with sex and fallen angels and revolution and shame. His body of work eroticizes Christianity and insists that transgressive sexuality and the elimination of shame is crucial for revolutionary politics. I think of this moment in Blake’s “Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion” when Los wipes the tears from its Spector’s eyes after singing: “O Shame O strong & mighty Shame / I break thy brazen fetters.” For Blake it is precisely the Christian legislation of desire that is productive of shame, and his whole thing is about understanding how sexual subjection is baked into a story about political subjection. Shame itself is a response to norms meant to create an inside and an outside—it is literally meant to reinforce borders. So unexamined shame—related to desire, sexual or otherwise—blocks the way of revolutionary struggle.

But to get a little more contemporary—poets associated with New Narrative writing were really formative for me in this regard: Dodie Bellamy, Kevin Killian, Harryette Mullen, Robert Glück, Nathaniel Mackey. In Glück’s essay on New Narrative he says “Bataille showed us how a bath house and a church could fulfill the same function in their respective communities” and the residue of reading through that poetic world stays with me. They write so beautifully about shame, scandal, community, and of course gay sex. In that same Glück essay, he talks about how Bataille’s theory of the pornographic allowed him “to arrive at ecstasy and loss of narration as the self sheds its social identities… Bataille showed us that loss of self and attainment of nothingness is a group activity.” Most of the poems that explicitly explore kink in my book are in a section called “Sovereign Exhaustion.” In this way, whether thinking with the “pornographic” or thinking with “kink,” poetry acts as a staging ground that allows for these massive sublimations and manifestations against the brutality of being a rational sovereign self at all. And kink isn’t just about exploring sexual desire, it is about power, consent, and care above all.

BLVR: I love that about the loose associative translation, and I agree with your insight about the elimination of shame. From my experience, people who’ve experienced shame value community very strongly, and I want to ask about your community.

RS: I love this question. As a structure of feeling, I love thinking about shame and I love to touch it—to understand how it structures our emotions, decisions, and unconscious attachments. There is so much information in shame about the invisible social contracts that we internalize and how they underpin a liberal condition masquerading as freedom. It is the feeling of recognizing one’s own total abject subjection to law. Being able to touch this symptomatic shame makes these contracts visible and lessons their grip on our relationships and intimacies. That’s what I mean by the elimination of shame—not the repression of it, but the surfacing of it, allowing its dissolution. Understanding how it functions in order to articulate desire as always against a law. If we can touch shame, it stops being a coping mechanism, and instead can be used as a resource for forging healing, pleasure, togetherness.

I am interested in a queer politics and queer poetics willing to examine shame-based fantasies, impossible ethical binds and contradictions. A poetics that brings into existence what’s been repressed or regulated into absence. Finding forbidden relations and loving them. That said, there are many artistic explorations of shame that extend the violence they purport to eradicate or atone for. I think the practice of engaging and representing shame requires an intense commitment to reflection, care, and accountability. (I’m not interested in confession, description, or absolution, except in extremely staged consensual ways—that’s hot.)

What you say is true for me too—my experience of community often coheres in response to shame arising from some shared form of regulation or subjection. But also shame and it’s deadly social expression as stigma and law is meant to alienate deviance from what is deemed common or shared: it is what not only separates us from ourselves but from each other. It is a response to the imposition of regulatory sameness. But what if we refuse to consent to what is presented as common or shared by the state, by regulatory norms? That’s where my impulse toward community—as this borderless sense of intimacies or alliances living under shared conditions—lies.

I also think “Community”—the creation of a “We”—is treacherous if it is predicated on sameness. I am drawn to intimacies that are collaborating against the institutions which regulate norms. I feel cautious about saying something like my community is ‘queer community’ even though it’s convenient. Perhaps it accurately communicates something fundamental about my friends and comrades, but as a label it obscures incredible differences and social forces that shape our lives. But as an act of refusal, the centering of queer desire—which is to say pleasure, decadence, luxury, care, laziness, excess— is something that shows up a lot in communities I exist in, rather than a sort of leftist asceticism as a way of saying ‘No’ to regulatory power.

BLVR: I wanted to ask a bit about the poems in the “Hagiographies” section, particularly the poem “I Work.” I wanted to hear your thoughts on work and “performance:” “My least dear fact / that only exists in its performance of my dutiful choral citizenship.”

RS: Work, definitely my least dear fact and something I spend most of my life trying to refuse doing. And yet, alongside that refusal, of course I have to work. And in every work situation I’ve been in, we’ve always been demanding a raise, demanding something more, or at least stealing time in the ways we could. I was thinking about this when I wrote the line: “I didn’t mean to ask for money, I meant to ask for a different/set of relations.” Even if the demand has to be better wages and better working conditions, the wage obscures the fundamental desire to change the capitalist set of relations that require worker exploitation.

A Hagiography is a life of a saint—and this section is about the “worker” and “work” as this glorified mode of entering citizenship and respectability. The worker is a figure which also can limit a revolutionary imagination. I was thinking ironically about this performative utterance “I work” almost as a declaration or proof of “goodness” under the logics of the state. As if being a “hard worker” for someone else’s wealth accumulation is a good thing, but also as if the worker is the dominant symbol of resistance and organizing potential. I’m thinking about the worker as this saintly figure that we want to contest. Through this perspective I am interested in anti-work politics of care, mutual aid, the relationships between labor organizing and abolitionist organizing.

A big theme I was working through in this section, and the previous “No Wages / No Muses” section, was questions of labor organizing in relation to immaterial labor, reproductive labor, and sexual politics. As I began writing this book my friend and poet, Patricia No, and I would joke with one another demanding “Wages for Muses” as a riff on the Wages for Housework slogan. This joke, which was also in some ways a real wish, addressed the extraction in our interpersonal relationships: what it felt like to be represented by another person. But the historic demand for a wage for reproductive labor has theoretical and historical limits. While it reveals the exploitative role of the nuclear family and household work in reproducing “the worker” as part of a history of ongoing primitive accumulation, it obscures the fact, as scholars like Angela Davis point out, that women of color and Black women have been doing waged domestic work throughout this political movement. The demand for the wage can’t account for the ways the division of labor under racial capitalism mobilizes racialized gender formations to uphold these divisions. The move from the demand for the wage to the refusal of the wage relation is me thinking with decades of political debates around this issue. The slogan I ultimately wanted to imagine was “No Wages, No Muses” as both a sort of communal proposal, historical fact, and a demand.

BLVR: How do you approach navigating the genre of academic writing against the other contemporary and “lowbrow,” casual writing that occurs in the book?

RS: Academic writing is incredibly difficult and counterintuitive for me. I much more easily process ideas and experiences through poetry. I basically only write in run-ons no matter how hard I try and think really associatively, which is not valued in the genre of academic writing. Often when writing academically (I am in a Gender Studies PhD program right now), I brainstorm my ideas in the form of poems. I’d like to think this isn’t just a case of my bad grammar, but rather I actually need poetry to think outside the disciplinarity of academia. Like Aimé Césaire offers in “Poetry and Knowledge,” poetry is a mode of refusing the grammars of Western epistemologies. I spend a lot of time studying political histories and critical theory, but studying doesn’t always take place in academic settings for me. Most of the time academic thought is years behind the more “lowbrow” forms of knowledge happening at parties, at protests, in casual convos with friends, the group thread. In writing this book I was engaged with a lot of theoretical texts about structural power, capitalism and subjection, but also writing in intensely personal and everyday ways. One thing a poem can do is offer a container for all that abstract language which describes both invisible systems of power and our most intimate daily encounters—I learn so much from this friction. It creates a new way to sense and feel how alienation structures our lives, and also cuts through it. Poetry feels miraculous to me in that way. It is a literal sixth sense.