Some of us live our adult lives—decades—and never realize what we are the best at doing, or what we loved doing the most, our calling, in other words. Or, if we realize it and can articulate it, we never get around to doing it.

Jason Molina was the opposite of this kind of person. He wrote songs, sang them in unique song structures, and recorded them. By all accounts he applied workaday ethics to song craft from his teens to around age thirty-five, when he succumbed to genetic propensities for depression and substance addictions and proceeded to medicate himself to death before he turned forty.

Molina produced staggering output for two decades, in a variety of settings and musical styles, nearly thirty records, depending on how you count the seven-inch releases, EPs and box sets. He also sent cassette demos to fans that wrote him letters and he handed them out to eager souls in person. He created fresh and original music throughout, influencing musicians such as the Avett Brothers, My Morning Jacket, Waxahatchee, Hiss Golden Messenger, and others, including many in Europe. That’s a good run, a lasting legacy.

Whatever natural talents were Molina’s—a singular vocal sound, for one—were matched by a profound willingness to work, to put in the time to hone the craft he wanted to be good at, and to stick his neck out there, to expose himself trying to do this work at the highest level he could muster. He found his calling and did the work. That’s not tragic.

To borrow a line from Toni Morrison, who grew up in the same Lake Erie steel town, Lorain, Ohio, as Molina, “Beauty was not simply something to behold; it was something one could do,” (her emphasis, from the 1970 novel The Bluest Eye).

In February 2018 I drove six hours to Lorain to visit with Jason Molina’s father, William “Bill” Molina, now age seventy-five and a retired science teacher who logged thirty-five years in the public schools in Lorain, and his sister, six years her brother’s junior, Ashley Molina Lawson, age thirty-eight.

When I arrived in Lorain I had a couple of hours to kill, so I drove to the vacant lakefront lot where Molina, his brother Aaron and sister Ashley had grown up in a trailer park. It was a bitter cold winter day, highs around twenty degrees and twenty mile-per-hour winds coming off the lake. Several inches of snow were on the ground. The Molina’s had the trailer spot on a cliff overlooking the lake. Waves from Lake Erie lapped on the rock jetty in a hypnotic manner, louder than I would have imagined.

Ashley had organized our meeting at the two-story house she shares with her husband and two young kids on a modern cul-de-sac just a few miles from the lake, outside Lorain. Her ten year-old daughter, Melina, was there for our meeting. Ashley had told me that her father might not make it. He could be reluctant to talk about old times, his memories bittersweet, and I understood.

But Bill was there when I arrived and he quickly talked with warmth and enthusiasm about his oldest son as a young boy:

“Jason was an old soul,” said Bill. “We used to say he was born at age thirty. And he used to say he should have been born a hundred years earlier. The thing is, he was very, very smart. His IQ was in the 130s. At a very young age he read our entire set of Encyclopedia Britannica’s from A to Z and he learned four languages—Spanish, French, German, and English. And even as a very young kid he woke up early and took a shower right away and he was always very clean and ready to start the day, ready to do something. The reputation he developed for waking up early and writing songs…he was like that as a little boy, too.”

The elder Molina continued: “But Jason also lived in a fantasy world inside his head.” Ashley inserted, “He had a spooky side to him, seeing ghosts and believing in supernatural paranormal things.”

Bill continued, “During the summer, Jason would lie on his back and look at the stars or clouds for hours. He also was very passionate about magic and the supernatural from a very early age. He asked for a magic kit when he was only four or five years old. People in our family used to call him a gypsy. We had some gypsy heritage in my family in West Virginia from generations back in Spain.”

“Jason was a drifter,” added Ashley. “I’ve always said he left home when he finished high school and I never saw him again.”

Bill chimed in, “Wherever he drifted he took things very, very seriously. He was always like that.”

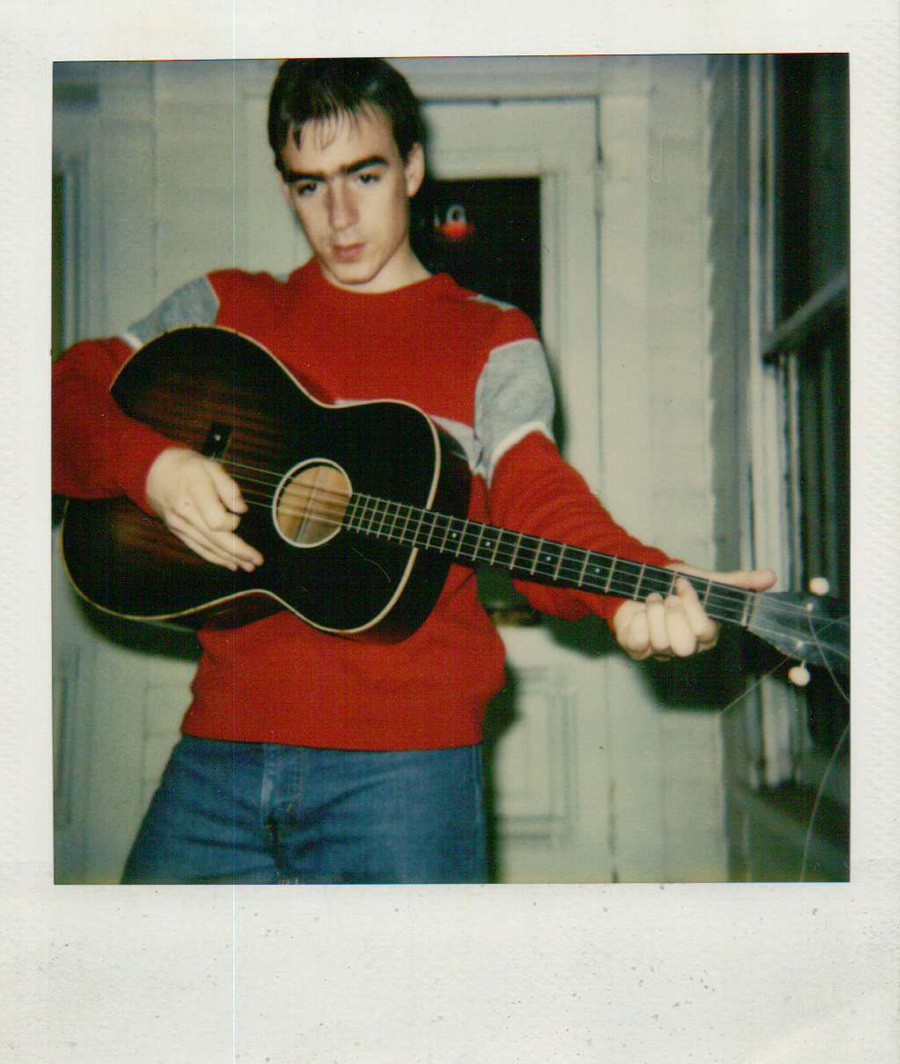

At age eight, Jason Molina was given his first guitar, a Fender. By ten he was asking his father to take him to Civil War reenactments and memorabilia shows. He also was fascinated by nature, particularly the Lake Erie shore where the family trailer sat for the first fifteen years of Molina’s life.

I mentioned my earlier visit to the family’s old trailer plot and Bill Molina beamed:

“It was great. We loved the sounds of those waves lapping. We loved the shore and everything about it. We had a little sandy beach almost all to ourselves and a little path down to it from our trailer. Now a bulkhead covers it all up. We swam and fished and we got out a telescope at night. We did everything down there. Jason loved it.”

In 1999, when Jason Molina was twenty-four years old, he was quoted in a fanzine called Copper Press saying this about his hometown:

“I grew up in a burnt-out shipbuilding and steel making town. Lorain is profoundly important to my music. It is the environment where I learned to walk away from the darkness. It is a place of water and storms and falling red sky and lightning. I learned to write music there about the world because out there it was immense and sudden. I learned that misery is not to capture but to learn about. Lorain and I have an unspoken agreement to always remain in each other’s lives. It is a hard place.”

The content of Molina’s adult life and work were drawn early.

“Love and work are the cornerstones of our humanness,” a quotation often attributed to Sigmund Freud but not found in his writings, cited by the developmental psychologist Erik Erikson, who had known Freud, in writing from 1963.

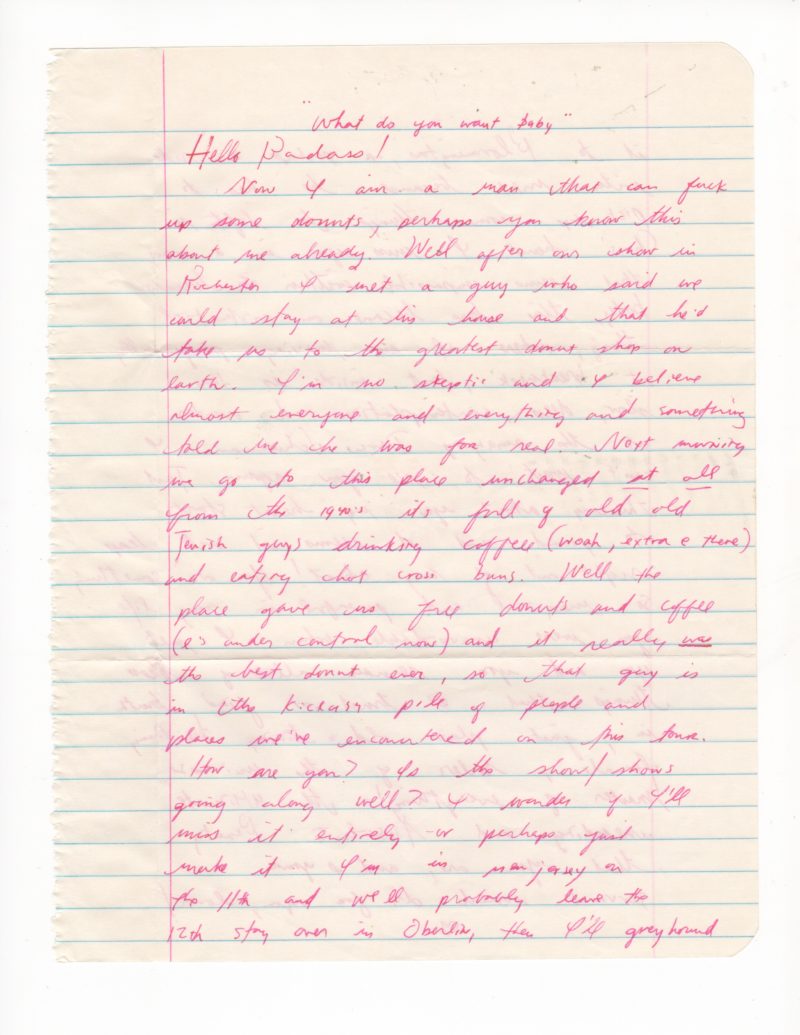

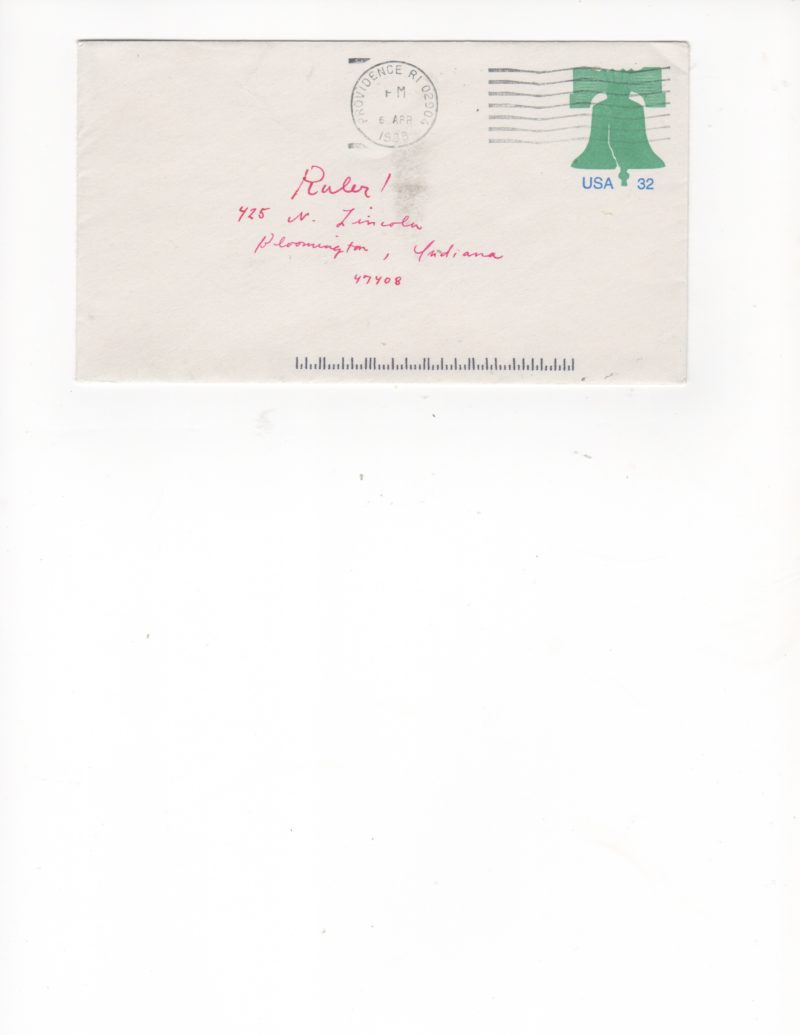

In his letters to Darcie Schoenman from the road during their twelve years together, married for most of that time, his words connect his work to feelings and needs for her, his passions swirling together:

“One thing I’m learning is that when art is true, and honest and real, it hurts. I’ve always had an idea of it but now I’m just hoping to gain strength from the way I feel about you. I think about you constantly and dream about you almost every night. I carry your picture with my guitar and see your smile before and after we play. I love you so much Darcie. Please know it, there could be nothing more simple or constant about my life than these feelings for you.”

The following lyric comes from the title song of his album containing his most overt love songs for Schoenman, “The Lioness,” released in January of 2000:

Want my heart to break if it must break in your jaws

Want you to lick my blood off your paws

It is for me the eventual truth

It is that look of the lioness to her man across the Nile

If not and you can’t get here fast enough

I will swim to you

During the sessions that produced “The Lioness,” Molina also recorded a series of unreleased “work songs” (his name for them) that are now being released, together with the love songs, for the first time (Love and Work: The Lioness Sessions, Secretly Canadian). This bundle of intertwining passions and dedications set a reverberating template for his life and more famous work to come.

To understand this reverb better, I sought the input of Kurt Zemlicka, a PhD in Rhetoric and a Lecturer in the English Department at Indiana University. Zemlicka is also a musician that grew up in Milwaukee, sharing post-industrial, lakefront background with Molina and who has studied these songs. He told me:

“Is Molina asking listeners to rethink the relationship between love and work? I think so. He is not saying ‘love is work’ or ‘work is love.’ Instead, what makes (this set of songs) so powerful, in my opinion, is that the listener is caught in an undecidable tension between those two formations, constantly reversing the relationship between the two, which creates a conceptual chiasmus that is richer and more developed than its components.“

Zemlicka goes on:

“The chiasmus is a rhetorical device used in literature and oratory that describes an inverted repetition, such as ‘When the going gets tough, the tough get going.’ The ancient Greek poets and dramatists loved the chiasmus largely because they could use it to signify a reversal. Molina has set up dozens of these reversals. I think the listener can begin to understand what he is trying to tell us about the nature of love, of work, and how the concepts continually transform each other.”

The alcoholism of Jason Molina’s mother is documented thoroughly in Erin Osmon’s excellent 2017 biography, Jason Molina: Riding With the Ghost. The Molina kids (Jason’s young brother, Aaron, now lives in Rhode Island) felt unsafe in the swerving car with their inebriated mother behind the wheel.

The abandonment felt by kids of alcoholic parents is a basic premise in the field of developmental psychology. The effects are insidious and lasting in adults. One of the effects is preoccupied relationship attachment, which often results in over-attachment and fears of new abandonment. Relationships like that usually have a limit or duration. But before they reach an untenable state those relationships can be highly productive if the attachment is reciprocated and the wounded individual feels safe and secure: extra work can be achieved.

In a paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in August of 1990, the authors write in their executive summary: “To learn about and become competent at interacting with the physical and social environment, one must explore. But exploration can be tiring and even dangerous, so it is desirable to have a protector nearby, a haven of safety to which one can retreat. According to attachment theory, the tendency to form an attachment to a protector and the tendency to explore the environment are innate tendencies regulated by interlocking behavioral systems.” In other words, shelter from the storm.

In the years that Jason Molina and Darcie Schoenman were together, he produced a voluminous body of work, songs written and also recorded, remarkably consistent with qualities of original depth and beauty.

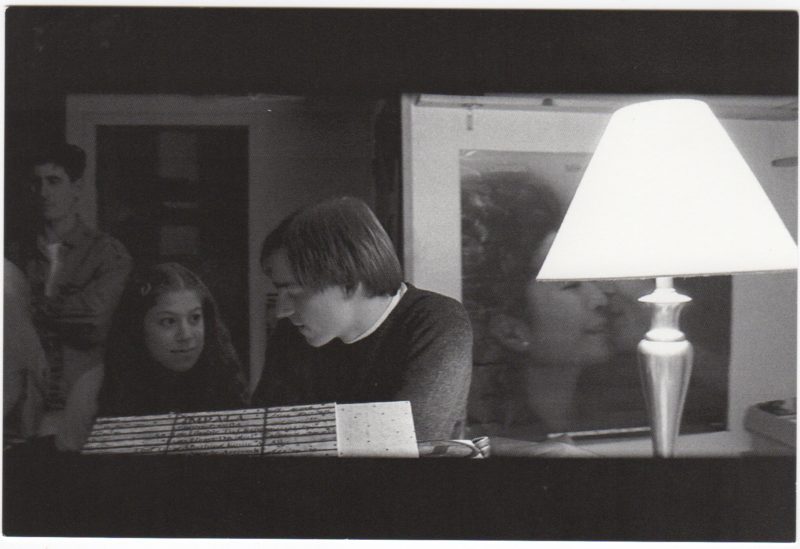

In the late 1990s, when Jason Molina wrote the love and work songs from “The Lioness” sessions, he was living with Darcie in a group rental house near Bryan Park in Bloomington, Indiana. The couple shared the main floor of the house while two other men in their twenties, Jason Jeannette and the latter’s cousin Cameron York, lived in the basement. Jeanette worked at Border’s Books and Music on the east side of town and he helped Molina get a job there, too.

Today Jeanette lives in Tennessee and when I called him he told me this story:

“I’ll never forget going to hear Songs: Ohia (Molina’s first stage name) perform at Second Story (a former club in downtown Bloomington) in 1998 or 1999. It was just Jason with his 4-string tenor guitar and I think just a drummer, just the two of them. You know, I was living with Jason and Darcie at the time and working with Jason at Border’s, so I saw a lot of him, and I remember being awakened to the sound of him playing his guitar early in the morning on the floor above us. But I had no understanding of what he was doing with his music until I saw that show. I didn’t get it. He played the song ‘The Lioness’ and his vocals, the lyrics, everything just sort of exploded off the stage. Just Jason and a drummer, that’s it, and it was profound. I remember wondering, how the fuck does he need a job at Border’s!”

Heather Whinna was working in Reckless Records on Broadway in Chicago in 1996 when Molina’s first commercial recording, a seven-inch single, “Nor Cease Thou Never Now,” was released by Will Oldham’s Palace Records. Whinna listened to it and felt moved to write a letter to Molina and mail it to the label. He responded by sending her a box of cassette demos.

Twenty-two years later, I called Whinna and she told me what moved her in Molina’s first single: “His voice… he sang like a bird. Something about the sound of his voice spoke to me so specifically and emotionally. It was nothing he said in particular; just the sound of his voice touched me. I can’t remember what I wrote him. He sent me this beautiful box of cassettes that he had lettered A to G and he had made ink drawings on the labels. The cassettes as objects were beautiful enough to look at.”

A few years later Whinna’s husband, Steve Albini, produced and recorded several of Molina’s most famous records in his Chicago studio. Sometime during this later period it occurred to Whinna that Molina might want his tapes back. “I offered to give them back and he said something that was unexpected at the time but now I couldn’t imagine him saying anything different. He told me simply: No. Please keep them. I like knowing they’re out there in the world.”

We are fortunate that Molina documented himself as much as he did. All he needed was a recorder and a room. His process, his love and work and way of life, made an imprint on many, and the results are still emerging five years after his death.