In a sexier and more exciting world, Kevin Killian would be a household name. For those already living there with his many books—including Shy, Argento Series, Action Kylie, Tweaky Village, and most recently, Tony Greene Era—it would be too easy to say that Kevin Killian is a writer’s writer; because his heartfelt, hilarious, horrific, horny, humanistic texts are an invitation to drastically reconsider what writing can do. Kevin wears a lot of hats: he is a gleefully corrupting patron of queer experimental literature; one of the most exalted reviewers of all-time on Amazon.com; and an inveterate collaborator whose work with visual artists, not to mention his own photography, opens onto ever-more surprising situations. With his wife, the writer Dodie Bellamy, he is the editor of Writers Who Love Too Much, a landmark anthology of New Narrative—an influential movement of sexually explicit, formally experimental prose that he and Dodie helped to forge.

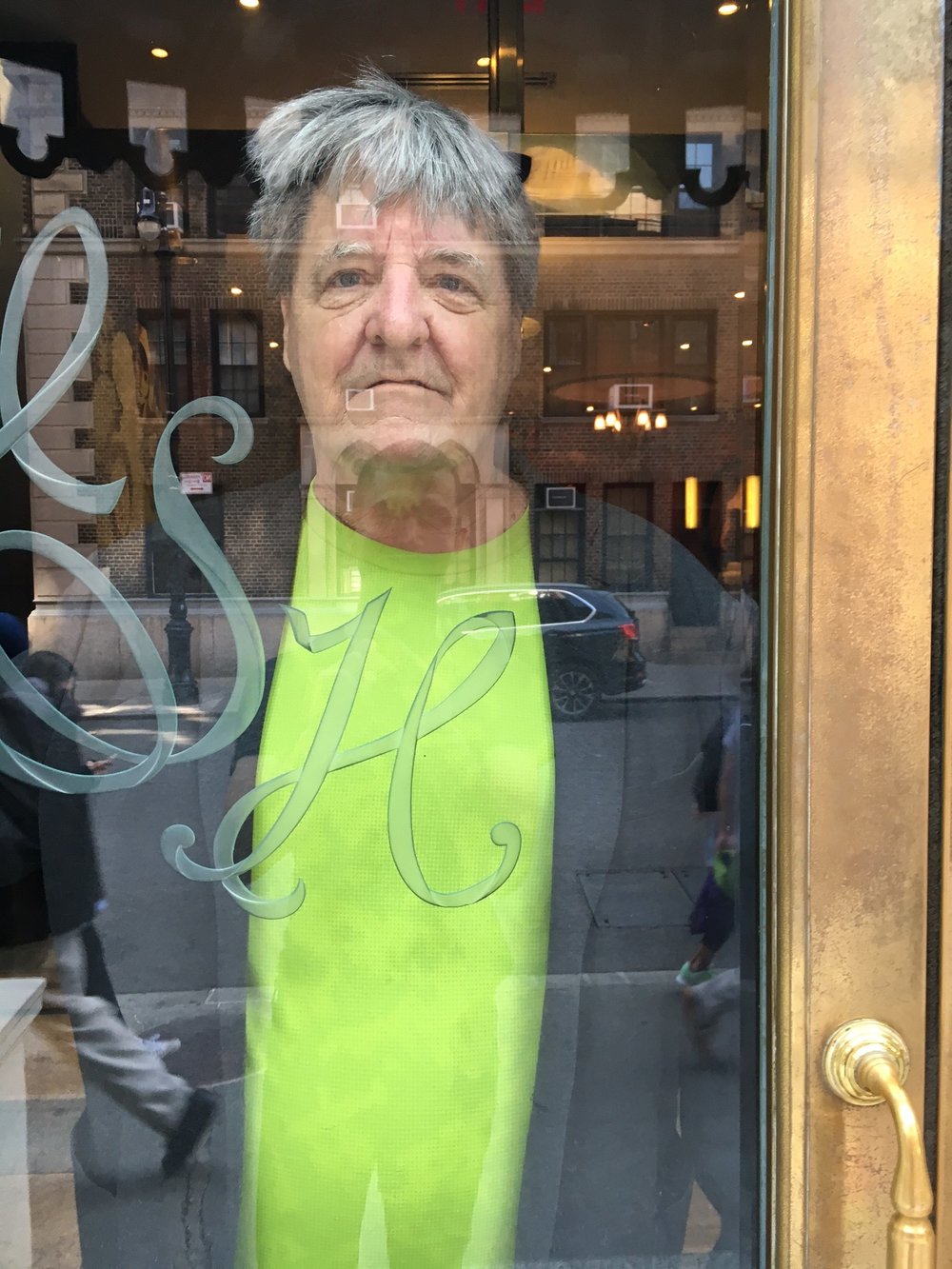

I caught up with Kevin in New York, where he was on his way to celebrate the 80th birthday of poet and artist John Giorno, hoping for dish. I wasn’t disappointed. Here’s a taste.

—Cam Scott

I. “Is it all over my face?”

THE BELIEVER: Let’s talk about your latest collection of poems, Tony Greene Era. Many of your books have a proper noun as a muse or interpretive key: Dario Argento, Kylie Minogue. So maybe I would start by asking, who is Tony Greene?

KEVIN KILLIAN: Greene was a LA-based painter who died in 1990, of AIDS. After his death there was a memorial show that traveled to a few places here and there, and a beautiful little book called Exhausted Autumn, in which poets and writers paid tribute to him. But then the world never heard of him again, or only in a rarefied context. Greene had graduated from CalArts with a tiny reputation. But of his cohort were a few artists who went onto great things—Richard Hawkins, Cathy Opie, Judie Bamber, Monica Majoli among them—artists who achieved enough cultural capital to join forces twenty-five years later and say, “Let’s bring Tony’s work back”. When Hawkins was asked to participate in the 2014 Whitney Biennial he said, “I will, if you’ll let me fill a room with Tony Greene’s paintings.” That made people sit up and take notice, as did the shows Opie organized at the Hammer, and Bamber and Majoli did at the MAK Center at L.A.’s Schindler House. I was sent to survey them for Artforum, and also brought in to give a talk at the Iceberg Projects show in Chicago, one which paired Greene’s paintings with works by younger artists inspired by his legend and example. And that talk formed the heart of my book.

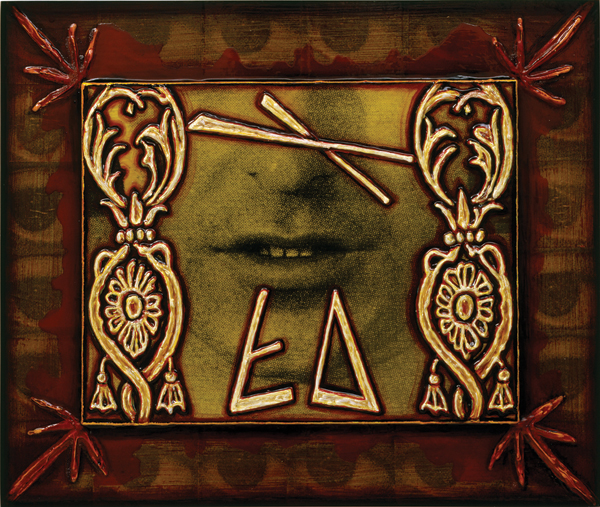

BLVR: Were those the over-painted pornographic photographs?

KK: So you saw them at the Whitney! Tony would clip pictures from boy magazines and paste them over fabulous baroque or renaissance backdrops, then redecorate them so each surface looked like it was touched with gold leaf. I gather that he had the AIDS diagnosis at a time when it really meant a death sentence, and maybe in one year’s time he was able to complete an enormous number of pictures, 50, 60, 70. I mean, it would take me five years to do one of those works. My figures may be way off, but it was in any case a large amount of work.

BLVR: So the time of those works coincides with the time of his illness?

KK: Some of them were created before he was diagnosed, perhaps. Seen in bulk they remind one of the richness and grandeur of a generation that we don’t really know what they would have been.

BLVR: It seems like Tony Greene is this emblem of a kind of bygone scene, “beautiful name that once spelled the future,” you write.

KK: Yeah, Richard and Tony weren’t boyfriends but they were very close. For LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions), the two collaborated on a mural, “Chains of Bitter Illusion” in the spring of 1988. For this project they decorated the outside of an existing building, and though parts of it are still extant, much has vanished via time, weather or new landlords. I was thinking about scaffolds hoisting painters up the walls of this Venice-style building to decorate it, and others later painting over their work. So I had to quote Brian Wilson’s “Surf’s Up” in it, in fact all my fantasies of LA life in the sixties and seventies.

BLVR: He seems like a site of pilgrimage in those poems.

KK: Yeah. The names in his pictures—Ed, or Al—would be painted in liturgical looking fonts, as those these pin-up boys were saints, so I imagine his name, Tony, as one of them. My poem is kind of an attempt to recreate some of his own effects, which were also largely derivative of other practices.

BLVR: Your writing does seem similarly hagiographical. When you talk about this mural being destroyed, it occurs that Tony Greene Era somehow mediates the specific historical and political stakes of your books Argento Series on one hand and Tweaky Village on the other, the plague years and the encroachment of capital and real estate. And it’s very elegiac for that reason.

KK: I guess I’ve always been elegiac, or maybe it’s just a queer person’s perspective, from having lived through a devastating age. A sacrilegious friend quipped that some of those who died of AIDS were monsters even in youth, even if one imagines them as beautiful creatures tragically lost, like Arthur Russell. Writing frankly about the real-life personalities of those who died of AIDS is always going to be tricky.

BLVR: Arthur Russell you knew, you have a cameo in his biography.

KK: I knew Arthur briefly, for a matter of months before I left New York and came to San Francisco. I kept up with him so little that I didn’t realize in his posthumous acclaim that it was the same person that I used to know. Reading an article about “Arthur Russell,” I’d think, “Isn’t that funny, I used to date someone named Arthur Russell.” Part of me must have believed firmly that the man I used to know must still be alive. When it sunk in, that really struck at the core of me, I think.

BLVR: You’ve written about him since, “Is It All Over My Face?”

KK: Tim Lawrence, Arthur’s biographer, read my poem and very charmingly asked me, “I’m not a poetry person, so I understand your poem so little that I can’t tell, are you claiming in this poem that you actually knew the real Arthur Russell?”

BLVR: I think I may have asked you the same fawning question.

KK: “Knew him? I had sex with him!” Gee, maybe the poem was kind of oblique. I was a really bad boyfriend and couldn’t get over Arthur’s looks. He was super talented and kind of a genius and a very handsome, Byronic guy but he had the worst skin I’d ever seen, and you know I grew up on Long Island where bad skin is endemic. So yeah, I just couldn’t deal with it, and that was it. That’s me as a shallow youth.

BLVR: I think that where the Arthur Russell icon is concerned it becomes him.

KK: No, it’s true. I looked at Matt Wolf’s documentary Wild Combination and thought, he’s so cute, why did you think he was ugly? In certain lighting—when it was so dark you could just see his beautiful eyes, his dashing cheekbones—he looked great. I wrote a prose account of my brief experience with Arthur for Tim Lawrence. Now I’ve taken that material and made it into a little book called Triangles in the Sand. Paul Chan of Badlands Unlimited will be publishing it. Though I knock on wood as one should always do till the cup hits your lips.

II. “This pile of Pettibons”

BLVR: We could talk about your ongoing photography projects.

KK: I played with photography on and off for years, but in the nineties for some reason I got out of taking photographs. When Kathy Acker died, I realized, ‘I don’t have any photographs of her.’ I thought I should just get a camera so I can remember these things better, and I started photographing copiously, mostly people. In a simultaneous development, Dodie and I became friendly with Raymond Pettibon, who gave me a pile of cut-out pieces of drawings that he was otherwise destroying. He would keep elements for future collage projects. So in this pile you’d see an autumn leaf, then an alarm clock, and the next one was a life-sized cock-and-balls that I imagine had once been part of a full-sized nude that he’d grown dissatisfied with and torn up. So when I saw this, I thought ‘this can’t go in a child’s book,’ because we were thinking of writing a children’s book…

BLVR: I hope that’s still pending.

KK: It has story construction problems, but Raymond made many drawings of spooky galleries and hideous paintings. The story is set in a haunted gallery in which the paintings eat children. One day a guest came over our apartment, Colter Jacobsen, and he saw this pile of Pettibons, with the dick picture on top. He grabbed it and put it over his own crotch as a joke and I thought, oh my god, that is so cute, let me get my camera. In subsequent months, every time that someone came over and I remembered, I shot their photo wearing this drawing. I must have had thirty or forty at the end of the year, and I had a curator come to look at them. He gave me a severe tonguelashing, a dismissal the likes of which I’ve never had from anybody. He said that the constant repetition of one subject just revealed what a technically bad photographer I am. “The only thing” said he, “that could save the situation is if you can talk somebody into posing nude with that drawing on his junk. Then you could intersperse that photo among these other pictures, and they might achieve an illusion of depth.” So I was in despair, I had no idea how I was going to save this situation. That very day we were having a party and one of the guests was George Kuchar, the filmmaker, and I told him how crushed I was by this curator’s opinion of my photography. And he showed me a video he’d just made that opens in a shower, and he looked great, at age seventy-five he had a fantastic body. I said, “George, you should do this, you’re not averse to nudity, and you’d be a real ‘get’ for me.” So he was my first nude model. In subsequent shows I would have a mixture of men with their clothes on and off; same with my book, also called Tagged. So since 2013, I’ve been working on this project. Dodie said ‘Why don’t you stop, you’ve made a success of this project and your book is its culmination.” But it’s been so much fun. I think that the very first time I met you, in San Francisco, I talked you into it. It’s a good icebreaker. “Now strip.”

BLVR: I recall hearing you describe the Pettibon package as a “promissory note,” does that ring a bell?

KK: Yeah, because the man is naked but he’s wearing this drawing over his dick, you could imagine that is what the real thing looks like. This is for people who are interested in you know, the actual phallus instead of the representation.

BLVR: I love how you impel your models, and I speak from experience, to perform this kind of awkward gesture which swaps nudity for nakedness, it shows in the face…

KK: To allow my models the use of their hands, I devised a primitive loincloth, a string around the waist, with a binder clip attached to either end. It’s ridiculous looking if somewhat sexy. I began thinking of actual genitals as being a thing of the past, like an appendix, something that has no use but is just there to represent something. I try to get my models to drop that drawing, as though it has crept away from them, and what they’re left with is their own body.

BLVR: There’s a description of that scenario in your poem “The Birth of Pallaksch”: “now our attention is focused on the string.”

KK: In that poem, which begins Tony Greene Era, I have a fantasy that one hundred thousand years from now, I won’t be here, but that drawing might be, and the binder clips and the string, as a memento mori of my attachment to my own cock.

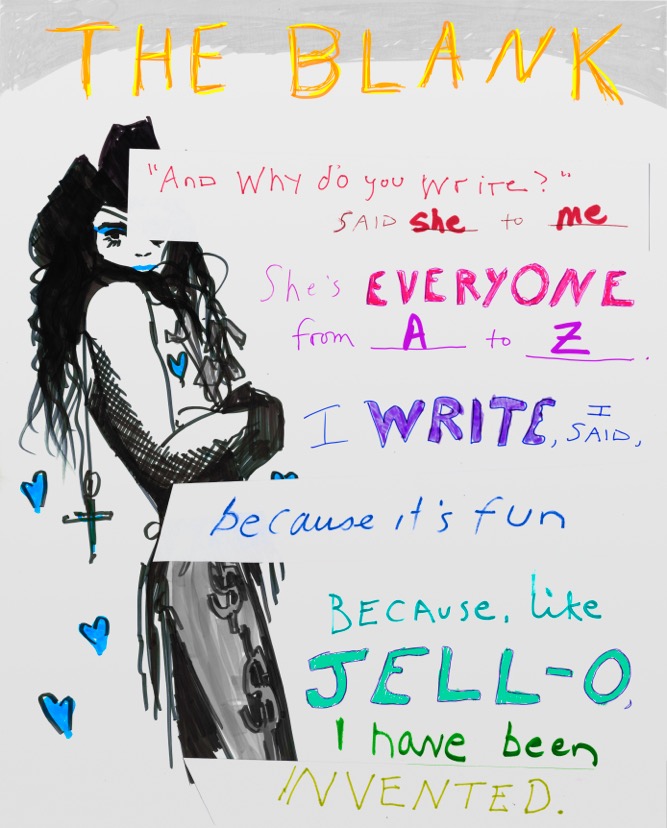

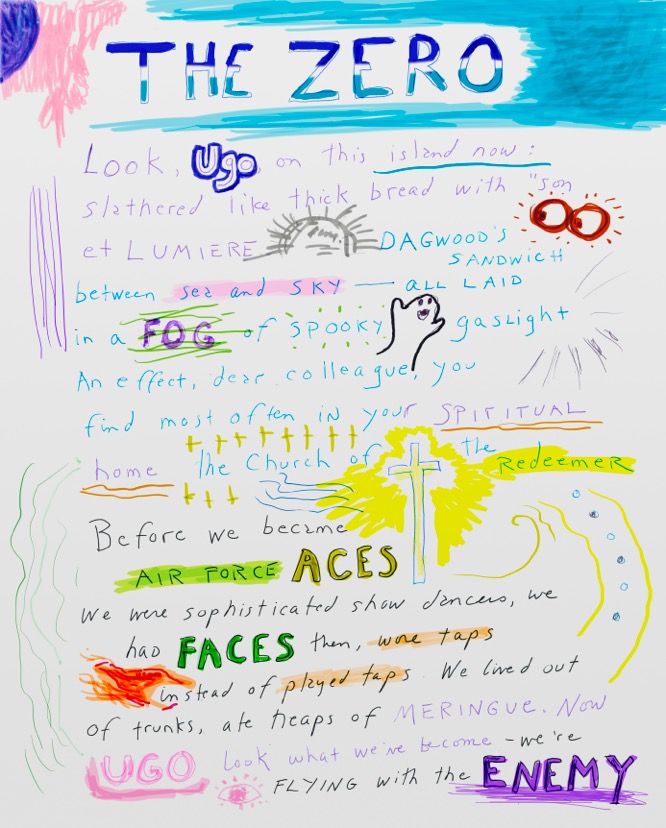

BLVR: Collaboration seems to be a motive force in your work. Some of my favorite tanka-length poems in Tony Greene Era were produced for a collaboration with Ugo Rondinone, correct?

KK: I’ve been working with Ugo for five or six years. He saw a poem of mine online, written out in my execrable handwriting for an online auction of manuscript pages of different poets, to raise money for the healthcare of one of us who was suffering. I took out a collection of Sharpies and touched up the holograph page—for sales appeal. Years later Ugo saw this, and liked it enough to sound me out about writing poems in conjunction with his first show at Barbara Gladstone, a show of sculptures called Nude. I read all those sculptures as people who were homeless, destitute. They were naked and recumbent, or propped feebly against the wall, looking like they were in their last moments. The poems I wrote and decorated were printed alongside collaged photos of Ugo’s sculptures in an artist’s book. For our next project, Ugo sent me a number of photos of paintings he’d been doing, windows, doors, and walls, and invited me to write poems about them. That’s what you see in some of the poems in this book.

BLVR: The rebus-like poems, you do all those illustrations?

KK: Yes, though I asked a friend, artist Daniel Samaniego, to draw the late Pete Burns for me, looking very androgynous and decadent, and my illustrations for that poem look amateur compared to his. But that’s what it’s about, showing a range of styles. Ugo would encourage me in wonderfully hyperbolic style. Once he said he had to rethink his whole conception of what drawing was when he saw mine. Why, he told me I possess “the color sense of a Matisse!” Anybody would feel encouraged, that’s what all we nascent artists want to hear.

BLVR: We could talk about Writers Who Love Too Much, the New Narrative anthology that you and Dodie edited for Nightboat.

KK: Dodie and I limited the contents to work created between 1977 to 1997. I had done a Poets Theater book with David Brazil that was organized on similar lines. For The Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater 1945-1985 David and I wrote a substantial introduction, and concluded with a series of long notes about each text. Dodie and I thought that tripartite structure would work for our New Narrative book. Like Poets Theater, New Narrative continues today, confounding even our own expectations. Until a little while ago we thought it was a failed experiment. That’s what’s so gratifying today, is that young people seem to get it in a way that previous generations couldn’t, I think, and the recent interest is why we got the commission to edit this book. Our book ends in 1997 with the one-two punch of Lawrence Braithwate’s Wigger and Chris Kraus’ I Love Dick, two very different culminations of what we were doing.

BLVR: Dodie and yourself are indissociable from New Narrative in a lot of people’s minds, but you’re quick to note that you only arrive on the scene in what, 1981…

KK: We weren’t there when Steve Abbott named it New Narrative, we weren’t there when Bob Glück and Bruce Boone wrote their books together. We were just eager students. I credit Bob and Bruce and Steve Abbott with teaching me how to write in general, though we were also living with Kathy Acker and Dennis Cooper and many other voices important to us.

BLVR: That sort of rigorous descendancy is perhaps not a productive framework where there are all of these unconsolidated energies in the air.

KK: I shouldn’t speak for Dodie, but I think that the two of us could see that what happened, say, with Language poetry is that it did prescribe this very much limited list of participants, and if you weren’t named among those twenty people well, you weren’t a Language poet, and that was fine for decades and it allowed them to take over the discourse for many years. But after awhile, if there are no new examples of it, then it’s going to wither on the vine, and people will begin to wonder, “What was the big deal about Language poetry anyhow?” I should add that for most all of us Language poetry was a life-changing force, one that couldn’t be denied.

BLVR: Not to cast stones, but I feel like the reverberations of that scene have a lot to do with the status of its core pedagogues, that it was imparted in certain corridors, if not strictly academic. And New Narrative seems much more plethoric and inviting…

KK: I don’t even know if schools had MFA programs when I started to write, no wait, there were, but only squares would join them! One of my students a few years ago confronted me with this, he said ‘I don’t want to embarrass you, but I’ve looked you up on the internet.”

BLVR: Ominous!

KK: It could have been anything, though my life is pretty much an open book. And he said, ‘I found out that you don’t have an MFA. Why do they let you teach this course?’ And I said yes, Chip, you’re going to graduate from this school in several months and technically speaking you’ll be better than me. But they hired me because I am Kevin Killian, because I’ve been around the block many times and written many books, and you will go on to have a wonderful career, but at the end of the day, you’ll never be Kevin Killian.

BLVR: It’s a credential that they don’t hand out to just anybody.

KK: He was stunned. But I think it’s because in grad school today, you are investing so much in getting that degree that it has to save your life, and you don’t want to hear that it’s not going to be the answer to all your problems.

BLVR: It doesn’t sound as though you took it very much to heart.

KK: It shook me up for a few days. As professionalization continues to increase, any moment now my job will go to someone with an MFA, no, a PhD. At least I can say I was there at the very tail end of teaching writing with no advanced degree.

BLVR: You hazard disputation when you do an anthology like this. People will ask “where’s so-and-so…”

KK: As soon as our book on poets theater came out, we were told of three plays that we didn’t know existed that I so wish had been in our anthology. One by Susan Howe, one by Larry Eigner, a third by Bruce Boone. Anytime you publish something you kick yourself, because you’re going to discover data that’s going to ruin your thesis.

BLVR: Where these late addendums are concerned, I recall that the last time we met you gave me a copy of Eyewitness, your 2015 book-length interview with Carolyn Dunn, who was a part of poet Jack Spicer’s Boston circle. You couldn’t find her when you were researching the Spicer biography, Poet Be Like God.

KK: And pow, she cast a new light on everything.

BLVR: And I think as you say it’s important to hear from women who interacted with Spicer…

KK: I’ve met one woman, the late Denise Levertov, who did not like Spicer—and she had good reason. But every other woman that I spoke to admired him, and was grateful to him, and noted him as someone who was actively interested in promoting women as artists. He has a bad reputation that I’ve tried to correct.

BLVR: Are you still working on Spicer?

KK: I’m editing a book of Spicer’s letters for Wesleyan with Kelly Holt. [Laughs.] And as soon as that book comes out, a new cache of letters will be discovered.

III. “Sub-Joycean burbling”

BLVR: You are perhaps one of the most prolific and authoritative Amazon reviewers of all time.

KK: I was in the top one hundred reviewers at one time—and because of that fleeting status, I remain in the soi-disant “Amazon Reviewer’s Hall of Fame.” I wrote these reviews as a therapy after an illness, when I had abandoned the pen because of a program of meds I was on that basically made me too happy to want to write. Dodie said, ‘You should write some reviews for Amazon. You don’t even need to write a whole sentence. It’s not like you don’t still have opinions, you just don’t have the vocabulary to say anything. So just write one word, like Horrible, or Great.’ And that made me feel like I was expressing myself. I got up to two words, and then a sentence. Those were happy times for me, when I was learning to write again. It took maybe two or three years to get back to my full strength as a writer, but after that, I could do the critical essays I used to write before my collapse. So I looked back and I’d written 1,500 of these reviews.

BLVR: I had no idea that it was that sort of a training course. I think of this lovely moment in The Buddhist where Dodie stops to register surprise at your obsessional output, how she hardly recognizes this side of you.

KK: My addiction has problems, you know, the obvious problem is that I’ve been working without being paid, in the service of a huge multinational corporation that is killing bookstores and perhaps writing itself. But some defended me and said, ‘he’s torquing the system from within, they’re not actually reviews, they’re poems.’ I remain undecided if I’m good or evil or misguided.

BLVR: Are you writing fiction right now? I adored Spreadeagle.

KK: I am writing a book but it’s going slowly because I keep getting interrupted by other projects. I started it when I was in college, and it takes place in the sixties. Did you see that Morrissey published a novel, List of the Lost, or Lust of the Last, or whatever…

BLVR: This is not a great year in which to profess Morrissey fandom, because he’s such an avid Brexiter and a crank, basically, but I read it the day it came out. It’s inscrutable, sub-Joycean burbling.

KK: Well, mine won’t be sub-Joycean burbling, but it will have a similar plotline. I was living in America in the seventies and that’s one thing I don’t remember, is all the high school boys obsessed with Margaret Thatcher.

BLVR: As I recall, Morrissey ventriloquizes them one by one. And the main character’s name is Ezra Pound.

KK: So crazy. I’ll put some puns in mine, but I want it to be more of a scary book than his.

BLVR: Spreadeagle is terrifying in moments.

KK: That’s what I was hoping for. And I do have readers who are horrified at what I write, readers who say it’s so cold and unfeeling and cruel. To a degree it’s Dennis Cooper’s problem, people don’t know he’s the sweetest man in the world because they’ve only read his books, which are horrifyingly Sadean, and they’re afraid to meet him. I’ve had some readers like that too, they read my books and they expect the worst. But in person I’m not bad.

BLVR: Far from it.

KK: Somebody pointed out that in all my novels it’s the same story. Innocent naifs come under the thumb of a charismatic, sadistic and destructive man. And they like it, up to a point.

BLVR: I think that a lot of people try to exonerate those sorts of stories by seizing upon the question of whether you’re identifying with the sadistic captors or the ravished, hapless victim. But I feel like sometimes the identification is dual.

KK: It is. I think it’s portraits of different sorts of consciousness. What would the world be like without evil people? Probably pretty good, but there wouldn’t be any novels written.

BLVR: Another thing I was going to ask, is there a collection coming out from Semiotext(e)?

KK: I’m delighted that Semiotext(e) signed Andrew Durbin—who’s written a novel himself, the fantastic MacArthur Park—to produce a kind of Kevin Killian Reader. He will reprint some of my earliest books, which aren’t readily available.

BLVR: Like Bedrooms Have Windows…

KK: That and Shy, my first novel, and some other materials from around that period. I was a late bloomer, I wasn’t even that young when I was writing those books, but I had the energy of a very young man, one with a million plans, one with ideas coming out of his ass. What we learned in New Narrative was that it didn’t really matter what you wanted to write, if that was a joke book or a series of wedding invitations it could also be a novel. At the same time, we heard that the most interesting material would come out of the worst things you’d done or the most embarrassing things that had ever happened to you. So that gave me an enormous amount of material to draw from.

BLVR: So long as you keep having embarrassing experiences, you’re set.

KK: Yeah, so long as I continue to do bad things. I can’t stop now. I’ve tried every year to be better as a person, to be more compassionate, forgiving, and to help people more. But they’re never going to take the Long Island out of the boy. My second novel, Arctic Summer, is about a photographer whose profession is to take nude pictures of as many men as he can, to exploit them and get them to take their clothes off so he can have sex with them. He’s the evil spirit in that book, his name is George, and he’s returning in my new novel, as an older man. When I started the photo project I lured you into, the realization came to me that I had imagined this demon photographer and then I became him.

BLVR: A lot of your readers have a special stake in tracking your appearances in fiction, including not only Dodie’s writing but your own. For example, Jarett Kobek’s novel I Hate the Internet commences from the fictional classroom of one Kevin Killian.

KK: In Michael Friedman’s novel On My Way To See You, my body is found washed up on the banks of the Seine. Next year, again knock on wood, I’m going to be in a book by Stephen Beachy called Glory Hole—I can only imagine what I’ll be doing in that. Jarett Kobek had written an article for Frieze about a now-defunct reading series in San Francisco that he presented as the last gasp of a dead Bohemia. That prepared me for my walk-on part in his novel, which has made me famous in a way I had never anticipated. He meant it as a beautiful compliment, that I’m the ambassador for San Francisco, there to welcome people and connect them, like Mister Gladhands. That is a big part of me, I guess.

BLVR: I don’t want to reduce you to that, but I spoke of your generosity, and to this degree, I do somewhat feel like we’re all in Kevin Killian’s classroom.

KK: We wrote these books, and one of the laws was, aside from saying the most embarrassing things you could think of, the more real names the better. There was this one man who was kind of a stalker. And he would write stories about Dodie and I in which we would be doing the most humiliating things. “I saw Kevin Killian today, boy did he look bad,’”things like that. In one he followed me into the backroom of a video store, and we had sex behind the curtain. In another one we went to the back row of the Castro Theater or somewhere like that and he gave me a blowjob. I shouldn’t object to that, it’s just one of the things that fiction writers do, isn’t it? Project themselves into other people’s lives.”

BLVR: In that way he is an exemplary heir to New Narrative, if a bit of a creep.

KK: Oh, he definitely was. He’d put these out as little zines, and sell them at City Lights.

BLVR: That’s how rumors get started.

KK: They were flattering in my case. My cock choked him! Because of that, my large genitalia was remarked on in Wikipedia. Every sentence in the article on me had at least one clause that was factually wrong. The publicist at Wonder Books (who put out Tweaky Village and Tony Greene Era) had a day job at Wikipedia, and offered to change the things that I wanted changed in my entry. I said, “thank you so much, and by the way you might leave that one line, “Many writers have commented on Kevin Killian’s oversized genitalia.”

BLVR: I’m obviously not doing the minimal labor required of an interviewer, I didn’t look you up on Wikipedia.

KK: Well, if this interview can be on the internet then someone can cite it later.

Purchase a copy of the current issue of The Believer here, and subscribe today to receive the next six issues for $48.