LITERATURE SICKNESS: EXPOSING REALITY’S MANY VALENCES

for Lynne Tillman

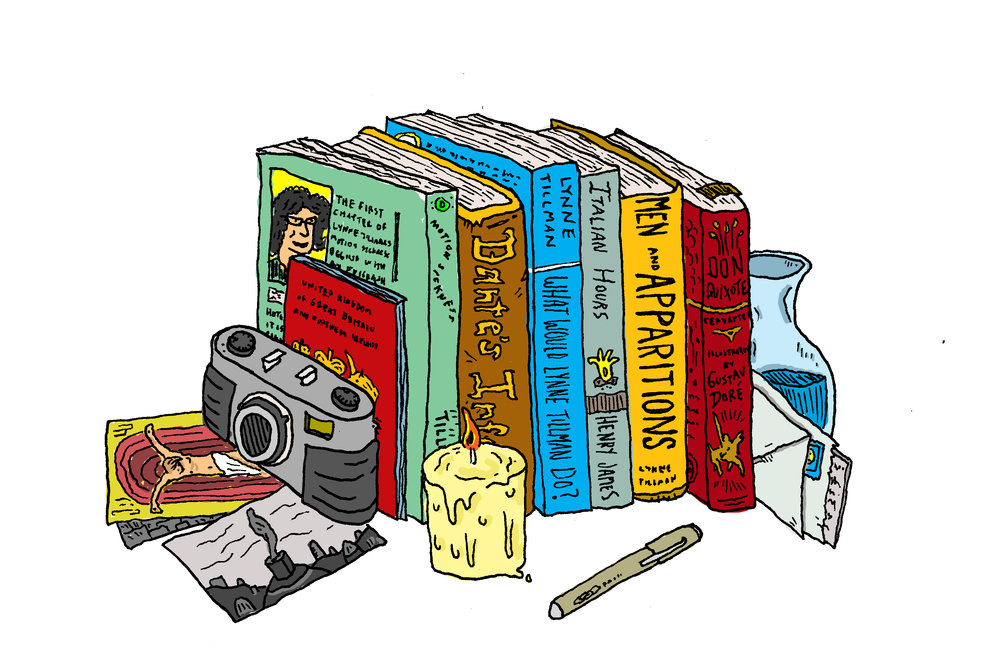

The first chapter of Lynne Tillman’s Motion Sickness begins with an epigraph by Flaubert: “I am… the fellow citizen of all that inhabits the great furnished hotel of the universe.” It is no coincidence that the chapter’s opening line echoes Flaubert’s epigraph: “Paris: I am in my hotel room, on the bed, reading The Portrait of a Lady, and nursing an illness I might not have.” This subtle grammatical gesture—the faint echo of Flaubert’s line—lends Tillman’s narrator an extra-literary dimension. The “I” that guides us through Paris, Florence, Istanbul, London, and Amsterdam among other places and that reads voraciously in various hotel rooms across European and non-European cities is, I propose, suffering from a case of literature sickness—a feverish obsession with reading and with viewing the world through the lens of literature. Despite being one of Tillman’s most overlooked books, Motion Sickness, locates itself firmly in the tradition of such idiosyncratic and paradigm-shifting novels as Robert Walser’s The Walk, W.G. Sebald’s Vertigo and Rings of Saturn, Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, Mat Johnson’s PYM, Gail Scott’s My Paris, Teju Cole’s Open City, and Enrique Vila-Matas’ Dublinesque and Montano’s Malady—all books whose DNA, in one form or another, can be traced back to Don Quixote (1605), the quintessential book about books.

Part philosophical diary, part travelogue, and part an examination of the constraints national narratives place on personhood and our perception of others, Motion Sickness begs to be read alongside a broad constellation of books that simultaneously use literature to expose the unreality of identity and to examine the poetic and geo-political dynamics of space. It is a book that deserves to be located within a lineage of novels that are securely tapped into the echo chamber of literature; books that are purposively in conversation with other books and within whose pages the genetic code of their literary forbearers is embedded. Though I am using Don Quixote as a point of reference here, it’s important to note that to write about reading is a preoccupation that runs through the history of literature: think of Petrarch reading Saint Augustine, Virgil reading Homer, Dante reading Virgil, Woolf reading Mansfield, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz reading Plato, Cervantes reading the chivalric tales, Acker and Borges reading Cervantes, Coates reading Baldwin. The list goes on. What I’m getting at is that in recasting an older text and/or embedding within their own text a rapport with another, each of these authors has created a book that will inevitably influence and transform our understanding of another author’s oeuvre, literary genre, or mode of writing. These writers—and I include Tillman among them—have innovated the technology of the novel or the poem precisely because they have been unafraid to look back, to plunge themselves headfirst into the history of literature.

Before examining the particular characteristics of Tillman’s Motion Sickness, I’d like to briefly return to the notion of literature sickness, a motif as old as literature itself and an illness that can be loosely defined by a feverish obsession with reading. While the compulsion to read threatens to erode the reader’s sense of reality, it also uncovers some hidden truth about the nature of the self in light of the very reality it is required to operate; in other words, it erodes one in order to unveil the other. The literature sick reader’s mind becomes consumed by literature and, as a result, their grasp of reality is supplanted by the logic of the worlds encased within the books they are reading. In its advanced stages, literature sickness can launch the reader into a fictional dimension that runs parallel to their contemporary socio-historical reality and that exposes the latter’s inherent contradictions and hypocrisies; it may even cause the reader to regard life with higher than average levels of paranoia, their sensory perceptions either hijacked or slightly distorted by literature.

To add another layer of complexity, literature sickness comes in many forms: it can effect real people with bibliophilic tendencies, or fictional narrators, or characters that may or may not be dramatized representations of real aspects of an author. In fact, some of our most iconic literary characters suffer from an acute form of literature sickness: Dante the Pilgrim, who turns to Virgil as his guide, is a fictionalized representation of Dante the exiled poet; Don Quixote: Knight of the Sad Countenance—a protagonist who, in his highest form, embodies philosophical questions regarding the nature of the mind—represents a parody of real readers’ obsession with the empty heroism of chivalric tales; more recently, Ben Lerner’s narrator in 10:04—a novel deeply invested in exploring authorial identity in relation to various facets of trauma and pre-cognition—is a fictional self-dramatization of the real author; Teju Cole’s narrator in Open City—a psychological novel that maps its narrator’s literary and artistic consciousness onto the page while exposing America’s stormy relationship with its largely unacknowledged history of racial violence—investigates identity vis-à-vis questions of ancestry and artistic legacy.

In tracing the coordinates of literature sickness, what emerges is a constellation of novels populated by isolated narrators who turn to other novels for counsel. And Tillman’s Motion Sickness, a novel that is as much about reading as it is about mourning and unpacking what it means to be an American abroad at the end of the twentieth century, belongs to such an inventory of novels that self-consciously take up the task of examining and reinventing the forms’ limits by turning to the history of literature for guidance while also confronting larger historical, political, and social adversities. At their core, books that explore what it means to inhabit life through literature are also examining the intersubjective nature of consciousness and probing the gap between perception and reality. This investigation is the axis around which novels about literature sickness spin and the chain of questions that emerge as a result are vast and varied: What does it mean to be human? How does the mind grasp reality? And since reality consists of multiple intersecting planes—imaginary, historical, religious, spatial, racial, sexual, and so on—what is the novel’s responsibility when it comes to the representation of reality? And, can we think of literary genre (and by genre, I mean modernism, postmodernism, naturalism, realism, etc.) as the novel’s ongoing correspondence with rapidly shifting planes of reality? While these are tough questions that often lead to inconclusive answers, they are existential in nature and therefore, as suspect as the term has become, universal.

ON MOTION SICKNESS: EXAMINING CONSCIOUSNESS ABROAD

As I mentioned above, Tillman’s nameless narrator—a young American woman who is traveling across European and non-European cities under the specter of her father’s death—introduces herself to us first through Flaubert and second through Henry James. She reads A Portrait of a Lady in Paris, a novel which James’ writes “was begun in Florence, during three months spent there in the spring of 1879.” In fact, Henry James spent many years between 1870 and 1908 living in and traveling through Italy, an experience he documents in Italian Hours, a collection of essays about an Italy undergoing vast social and political transformations as it approached the twentieth century. Tillman’s Motion Sickness, which is in large part an investigation of memory and space, and which examines the reality of what it means to be an American in Europe at the end of an era, so to speak, takes place in the final decade of the twentieth century, nearly a hundred years after the publication of James’ A Portrait of a Lady and Italian Hours. Even more interesting, perhaps, is the fact that, much like Motion Sickness, Italian Hours is loosely structured and could, if were we to apply the same criteria used to judge Tillman’s novel nearly a century later, be described as “lacking focus,” as an underdeveloped and embryonic amalgamation of a flâneur’s musings. But James’ Italian Hours and Tillman’s Motion Sickness rebuff such reductionisms. The structure of both texts reflects the chaotic rush of technological innovation and the redrawing of national boundaries that accompanied the final decade of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. While in the case of James’ travelogue the gravitational center rests on the heels of the unification of Italy and the Haussmann style renewal of Italy’s urban centers at the close of the nineteenth century, Tillman’s observations are a preface to the development of the world-wide-web and the move toward globalization that would eventually lead to the establishment of the European Union. Both books take the reader through several cities out of chronological order, causing a sense of temporal and spatial disorientation that mirrors the ebb and flow of a world on the cusp of a massive transformation. In his introduction to the 1995 Penguin Classics edition of Italian Hours, John Auchard writes:

The title “Italian Hours” provides a broad context for consideration—slightly sacred, partly artistic and impressionistic, and partly, and literally, anachronistic—made especially uneasy by the relentless and erratic ticking off of hours and years. The suggestion of confounded time and of resolute temporal progression may help explain a troublesome feature of these articles, the fact that when they were collated in the 1909 first edition they were arranged without respect to the chronology of their original publication. Perhaps James intended to communicate a sense of time out of joint, and therefore the book begins in Venice in 1882, moves to 1892, back to 1872, up to 1899, and so on throughout. The effect allows some correlative of the traveler’s experience in Italy, lost in the fourteenth century, thrust into the twentieth upon entering the piazza, allowed to reclaim some nostalgia while walking down an avenue of ilexes, but increasingly disoriented along the way.

Tillman’s Motion Sickness echoes this sense of “time out of joint.” Each chapter is subdivided into several vignettes that correspond to a variety of cities and are presented out of chronological order. This atmosphere of disorientation is further amplified by the blurring of boundaries between the real and the fictional that results from the narrator’s obsessive reading habits. In the first chapter alone we are taken through Paris, where the narrator reads A Portrait of a Lady; Istanbul, where she reads Mickey Spillane’s My Gun is Quick; Agia Galini, where she refuses to leave her hotel room because she is reading; Istanbul (again), where she reads The New York Times and the Herald Tribune; Amsterdam, where she reads Horace McCoy’s I Should have Stayed Home; and Istanbul once again, where she walks through subterranean tunnels with an Englishman named Charles before returning to Agia Galini, and then London where we meet another American woman named Jessica, whose disappeared husband turns out to be Charles, the very man our narrator met in Istanbul. Jessica, it so happens, is reading Henry James’ The Europeans while our narrator has moved on to The American. In a novel charged with coincidences, it is safe to say that launching us into its pages with a nod to Henry James isn’t one of them.

The reference to A Portrait of a Lady in Motion Sickness’ opening lines provides us with a literary compass we can rely on both to help us navigate the novel’s own subtext and to orient us within a larger literary landscape, one in which Henry James, despite being a maximalist where Tillman is a minimalist, occupies a privileged position. The most obvious link between A Portrait of a Lady and Motion Sickness is that both novels feature young American women who have defected to the Old World in search of a new identity, a kind of tabula rasa, only to become plagued by memories of the past and engulfed by a series of morbid pleasures that reveal to them their personal, cultural, and historical limitations.

But more compelling than that, however, is the overlap between Tillman’s novel and Italian Hours, a book that I consider to be a companion text to A Portrait of a Lady, not only because James wrote the two roughly around the same time, but also because Italian Hours provides us with insight into James’ mind as he considered his own reality—the metaphysics of his interiority—from the vantage point of the Old World. Like Tillman, James lays bare the ways in which our subjectivities take flight in or are taxed by the spaces we inhabit. Following the tradition of European journey narratives, Tillman’s narrator gains purchase on her reality as a result of traveling through Europe. Three pages into the novel, in a section titled “Istanbul,” she considers if the hotel manager likes her and writes:

I decide he does like me, as I have a need anyway to feel I am liked. No doubt this marks me as an American. I must be full of national characteristics that are hidden from me and are palpable to others, to Mr. Yapar, for instance, as home becomes palpable to me only because I’m not there.

By the end of the chapter we are in London where the narrator regularly shows up late to breakfast at her hotel. She does not care that this gesture might elicit the staff’s dislike of her. She refuses to get out of bed early just to avoid being hated and considers this rebellion against her former tendencies a sign of progress. This newfound estrangement from her past self rewards her with a curatorial eye that she uses to scrutinize how her subconscious needs might be informed by larger national characteristics. In other words, she is no longer oblivious to her Americanness and this insight allows her to edit certain parts of herself, to become less American.

The footprint of identity and nationhood becomes more marked as the novel progresses. Tillman’s narrator becomes increasingly discerning and suspicious of the mechanisms through which national identity infiltrates and lends structure to our individual subjectivities. About a fourth of the way through the novel, while traveling through Tuscany with two British brothers she writes:

To complement Alfred’s and Paul’s words I follow their facial expressions and gestures, neither of which give away much. It’s perplexing to understand so little in our common language, a dilemma that connects me to so many other Americans, I should feel a sense of community but don’t, except in the negative sense.

Much later, having gone to Tangier, she reflects:

National identity is like armor. On permanent loan from a museum. It’s dull armor that I clink around in. Could I get an operation that would make me oblivious to symbols? Could I be like a human Switzerland, always neutral to the partisan demands of birthplace? Get a transnational operation, get placed in a different body politic?

And finally, near the end of the novel:

If I defend myself, do I defend my country, as if it and I were the same, which begs the question of how and to what extent these things can be separated. Do I claim the country or does it claim me?

It’s curious to note that Henry James, whose life was firmly anchored in the Old World by the end of the nineteenth century, succeeds in getting a “transnational operation.” He becomes considerably less American over the course of his life. His Americanness recedes into the distance, becomes vague and remote, allowing him to pass through national barriers like a ghost or a medium who, before being eclipsed by physical death, was able to occupy a different body politic. James, whose returns to America virtually ceased toward the end of his life, acquired British Citizenship in 1915, a year before he died. In the works of both James and Tillman, the motif of death and transgression take flight alongside the exploration of national identity and of consciousness.

The desire to “transgress”—the yearning for a transformational experience that allows us to overcome the oppressive imprint of our nation-state of origin, to become free of the way each of us is, in Tillman’s words, a “codicil for one’s nation”—is never fully achieved in Motion Sickness. It is perhaps at this juncture that she parts ways with James. In Tillman’s view, we cannot entirely remove the national armor we were clothed with upon birth; there will always be a residue of prefabricated national identity to contend with in our day-to-day life. The ambition to “transgress” is interrupted by the material realities of our national condition. Though James and Tillman share an interest in communication and misunderstanding, in symbols and technology, his obsession with transcribing the life of the mind leads him to blur the boundaries between his characters, their objects, and the places they inhabit, while Tillman’s characters are often struck dumb by the hard surfaces of life, by the very impenetrability of things. Her characters’ attempts to transgress various facets of their story are often juxtaposed by the limits of their circumstance; they are rudely reminded of their lot in life.

In Motion Sickness, this motif of stalled desire is echoed by a series of unsent postcards which the narrator collects, writes on, and addresses only to tear up or to keep in her private archive of accumulated objects. By remaining unsent, the messages written on the postcards are never transmitted. In other words, the aspects of self that correspond to those messages are ultimately not deployed back across the Atlantic. The narrator’s language remains unmediated by the intended receiver of the postcard; her message is not circulated and therefore cannot acquire new emotional, intellectual, or linguistic dimensions. Much like the desire to transgress one’s national identity is disrupted, so too is the desire for communication—the fantasy of effective information exchange—suspended.

The narrator’s refusal to send the postcards she purchases reveals the author’s linguistic anguish and her belief in the potential language offers for intimacy. By holding on to the postcards, Tillman’s narrator is creating a collection in the Benjaminian sense; her refusal to enter the postcards into the mechanical circulation of letters suggests an attempt to restore their aura while knowing full well that they have been drained of any such potential by virtue of being reproductions. Tillman writes:

I leave books in hotel rooms when I’ve finished them. I hold on only to the pictures, the postcards, my playing cards that mark presence and absence. The more the days that pass seem like dreams, the more my dreams seem mundane, real. Friends crowd the frame. Fights are refought, humiliations and fears paraded, crazy dialogue intrudes upon a few sensible sentences, I am many different ages. The world ends. Images are fixed and unfixed.

Not long after, during an extended internal monologue, the narrator confesses that, contrary to some of the travelers she has met along the way, she does not believe that she will be able to emerge from her journey an unscathed victor who has succeeded in finding her true self. While considering her friend Sylvie, to whom she relates with a kind of clinical detachment as if she were a “camera or a tape recorder,” she reflects: “When Sylvie watches me and clasps her chin in her hand, she seems to expect that I might strip, the way she thinks she does, that I will be able to know my true from my false self, that like her I’m searching for it, facing the blank page as if it were a mirror.” Tillman’s narrator holds on to various facets of her self—whether they be true or false, present or absent, with or without aura—the same way that she holds on to the pictures and the postcards. She accumulates aspects of her self and their corresponding objects in a private archive through which she can shuffle at her own will and from which others are barred. The retention of postcards can be read as a metaphor that expedites the process of estranging herself from her past, of becoming a kind of reproduction of her previous self, or, to return to Benjamin, a collector of selves.

Henry James’ work reveals a similar kind of communication anxiety; his later work, more layered and obscure relative to his early novels (due in part to the fact that he was dictating them to a typist), demonstrates a progressive inquietude with language’s ability to locate and translate consciousness. Throughout his writing career, James becomes increasingly obsessed with the life of the mind and with transcribing its activities onto the page. Joseph Rosenberg, a James critic and modernist scholar who traces representations of paper as “excess matter” in his book Wastepaper Modernisms, unearths the many ways in which James’ work focuses on messages that have not been delivered or that have been misunderstood. In the book’s opening chapter, titled “Henry James’ Literary Remains,” he writes:

[…] paper gives a corporeal body to the missing, the lost, and the unspecifiable. But, as we shall see, giving what is absent the illusion of a material form is not quite the same as making it present. Rather, it is really only a process of substituting one form of blankness for another. Paper, for James, is a medium for connecting nothing with nothing.

This double gesture—of linguistic despair on the one hand, and of valuing language on the other—is something that, along with a dramatization of the ways in which communication technologies distort and mediate intimacy, pervades James’ work. Like Tillman, he too was interested in miscommunication, or in the inability to ever fully transmit consciousness. But while he may have harbored some belief in language’s ability to cull the depths of character, Tillman, who is writing in postwar America, more readily accepts language’s inherent failure to accurately document and record the self. This belief is mirrored in each author’s syntax: despite the fact that their writing shares an oral quality, James’ sentences are serpentine, meandering and are ornamented with what some might consider excessive punctuation while Tillman’s are succinct, direct, and full of a spontaneous verve. And yet both authors examine what it means to withhold their letters from circulation, in simultaneously attempting to establish and question language’s ability to mediate intimacy. While reflecting on letter writing as a “system of exchange” in James’ The Aspern Papers, Rosenberg writes:

I write an intimate letter, seal it, and send it to you to reopen, read, and then store away (and, if you happen to be Henry James, eventually burn).

James’ dramatization of the ebb and flow of consciousness on the page—his simultaneous passion for and mistrust of language—lead him to rather whimsically describe himself as an obscure writer in a 1913 letter to Hugh Walpole, which Rosenberg cites. James confesses to Walpole: “I am truly an uncommunicating communicator—a beastly bad thing to be.” Not surprisingly, in an essay dedicated to Tillman and titled “No Innocent Abroad: The Fiction of Lynne Tillman,” British literary critic and Americanist scholar Kasia Boddy writes:

Tillman’s belief in the social and ideological limits set by language sometimes results in moments of Beckett-inspired linguistic despair, yet it is a despair that is never indulged. The paradoxical nature of the writer’s relationship to language—”I distrust words and yet probably they are what I value most” (Tillman)—informs all of Tillman’s work.

Both James and Tillman conceive of the relationship between language and the self as a two-way autobahn intersected by reality’s multiple planes; their work reveals an instinctual recognition that language and the self are in a complex dialogue and that they coexist in a mutable matrix, a web-like network that is always shifting. Both writers are what I like to call linguistic deterritorializers or, in James’ words, uncommunicating communicators. In her essay on Tillman, Boddy writes that “Much of Tillman’s prose emulates the carefulness and self-awareness of someone using a second language as a way, as [she] says, of ‘inconveniencing the majority language’.” Boddy goes on to quote the narrator of Motion Sickness, who claims: “It will probably be my fate not to learn other languages but to speak my own as if I were a foreigner.” While Tillman’s narrator may not succeed in getting a “transnational operation,” she can, at the very least, manage to become a stranger to herself, to perceive aspects of her behavior and identity as uncanny, perhaps even alien. She can succeed in becoming unrecognizable to herself.

After all, in addition to being spatially displaced—a foreigner abroad—the narrator in Motion Sickness is mourning her father’s death. This fact further complicates the motif of otherness. To begin with, the novel’s maze-like structure, which is composed of vignettes strung together out of chronological order, amplifies the vertiginous effects of her grief. Three-fourths of the way through the novel, the narrator notes: “Death is terrible. A while ago, my father died, and life changed.” On the next page, she relays to the reader words she has previously spoken to Sylvie: “[…] death is like a one-way journey and it triggers in the ones who don’t die—it triggers an ordinary craziness.” It just so happens that in the same chapter, we are introduced to a series of postcards—a meager handful—that have been sent and received by the novel’s cast of characters. What has so far been carefully avoided—linguistic contamination and information exchange—finally occurs. But, even so, the narrator can’t be sure if the messages have been read or not, or if they have been correctly interpreted. Not incidentally, the star of the show is a postcard of Velazquez’s Las Meninas which is “still taped,” she writes, “to Arlette’s refrigerator though now it’s next to the Picasso I sent her, the one of the Infanta.” Picasso’s painting of the Infanta is one in a series of the artist’s reproductions of Velázquez’s Las Meninas. And though the narrator confesses that “she does not know if a painting can wear meaning,” the reader can’t help but read the various references to Velázquez’s painting—arguably the most famous representation of the vanishing point, a space receding to infinity without end—alongside the nods to Henry James whose sentences seem to pile on and on in order to give us the illusion of depth, of a consciousness that exceeds all limitations, transgresses all boundaries. So, in addition to inviting us to become literature sick, Tillman’s labyrinthine novel infects the reader with a sense of vertigo: it makes us motion sick.

This motion sickness has as much to do with the novel’s content as it does with its form; with Tillman’s general reticence toward plot-driven books with a clear beginning, middle, and end. Tillman’s literature resists compact narrative structures and instead mirrors the sprawling rhizomatic architecture of consciousness. In her analysis of Tillman’s unset postcards (itself a form that the vignette-like structure of the novel emulates), Boddy describes the narrator’s resistance to closure as a defiance against the finality of death. As someone whose conception of time is not linear and for whom death is a kind of transformation, a frontier rather than a barrier, I would add that the dizzying structure of Tillman’s Motion Sickness simultaneously reflects the inconclusive nature of life—a life composed of a series of events with a vague relation that bar interpretation—and the revisionist and fictional nature of memory. Doubt and interrogation, rather than plot, are the novel’s great to do.

In fact, examined from a broader perspective, it can be argued that Motion Sickness is structured the same way that involuntary memory operates—drifting on and off the stage of consciousness in a series of associative leaps across the void left over after the source event has passed. But just as there is a tension between the need to transgress and the reality of our limitations and between the desire and refusal to communicate, the novel also explores the balance between memory and the absence of remembrance. In a style reminiscent of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Tillman eschews backstory. She provides us only with sparse details about her narrator’s past. The few facts we are informed of—that she is a young American woman whose father has passed away and who is traveling on borrowed money—are presented slyly, nonchalantly. Rather early on in the novel, the narrator casually tells us:

I remember my father talking about someone’s being out of his element, which is, I suppose, one way to put it, my trips in foreign places. But I can’t write my father a postcard because he’s dead. Sometimes I forget that.

After this initial introduction, memories of her father sporadically appear on the page; the text behaves much the way involuntary memories function in life. A little later, while in conversation with Jessica (the American woman whose husband has disappeared and who is also reading Henry James), to whom the narrator has by now confessed having met Charles, the narrator provides us with privileged information. She delivers an aside that establishes an intimate link between the narrator and the reader while simultaneously providing us with the necessary instructions for how to read the novel:

That’s what I do, hold on to memory. You relive memories, you develop them, you make them bigger and better and add a touch here and there, like a dab of perfume behind the ear of a memory. Death gives you a reason to remember, to put it all together. To put together a new body, of evidence, of evidence of love, of evidence of something solid to battle the ephemeral. People always say you shouldn’t live in the past, but that’s so stupid because it’s not a matter of will, it’s not voluntary. A person without a past is like a nation without history. It’s impossible.

From this moment on, questions of death, memory, language and national identity become interlinked, forming a network that sustains the novel’s unruly stream of events and its non-linear architecture that moves us across the Old World in what might seem like a series of haphazard digressions and returns. But it’s this very exhaustion of space and memory that allows meaning to emerge. If the novel were a house, its rooms would be randomly duplicated; each room’s copy would return at steady intervals to reveal new information and to allow knowledge and therefore meaning to accumulate in sections through repetition. Recognition and misrecognition, memory and forgetfulness work together to simultaneously affirm and challenge the narrator’s ability to adequately represent her perception of an ever-fluctuating reality, a reality that, to return to Henry James, “comes in a myriad of tones.”

Examined from the vantage point of psychogeography, the narrator’s ambivalent circling and re-circling of space reveals itself as a futile exercise in urban spectatorship: she drifts through the Old World in the hope of getting farther afield from her past and, therefore, of gaining purchase on her identity, but this investigation of character as mediated through space is undermined by her recognition that there is no true or singular self to be discovered. The “impenetrability of a city’s daily life,” she writes, “casts a veil over ordinary perception.” For the narrator, the city—all matter—is impenetrable precisely because it is not fixed; like the self, it too is a palimpsest of time, a harbinger of multiple planes of reality. In fact, the narrator of Motion Sickness can be thought of as an existentialist detective: as someone who takes immense pleasure in observing her surroundings without necessarily comprehending them. We can also view her as what, in his analysis of Henry James, Rosenberg refers to as a “flaneur manqué: not a detached decipherer of urban experience, but an oblivious gawker.” He goes on to write that for the flaneur manqué “all messages and all signs are a form of uncommunicating communication: just so much blank matter.” And if the world is composed of a series of impenetrable intersecting surfaces that transform and reflect back to us the nuances of our consciousness, the only thing left for writers like Tillman and James to transcribe onto paper is the flawed and fluctuating nature of perception.

In both Motion Sickness and Italian Hours this investigation of consciousness broadens into a prolonged meditation on the bridges and gaps that exist between reading the city and its representations in art and literature. While James and Tillman recognize books as a form of media (after all, texts transform our consciousness and mediate our perception of the self and of space), and while they both document their perceptions of the Old World as it slides into a new century, they also share a deep suspicion that language can effectively lead us to recognition. Though operating nearly a century apart, their narrators adopt a mocking stance toward travel guides; they reject the form’s inherent claim to have pinned down the character of a city and its people. By distancing themselves from the tourist’s attitude of consumption, they are carefully positioning themselves as travelers, or as failed tourists who are content to gawk at the city without a defined objective.

In one of the more humorous scenes in Italian Hours, James attempts to read Ruskin’s Morning in Florence while walking through the city, a guide book he considers utterly objectionable:

I had really been enjoying the good old city of Florence, but I now learned from Mr. Ruskin that this was a scandalous waste of charity. I should have gone about with an imprecation on my lips, I should have worn a face three yards long. I had taken great pleasure in certain frescoes by Ghirlandaio in the choir of that very church; but it appeared from one of the little books that these frescoes were as naught. I had much admired Santa Croce and had thought the Duomo a very noble affair; but I had now the most positive assurance I knew nothing about them. After a while, if it was only ill-humour that was needed for doing honour to the city of the Medici, I felt that I had risen to a proper level; only now it was Mr. Ruskin himself I had lost patience with, not the stupid Brunelleschi, not the vulgar Ghirlandaio. Indeed I lost patience altogether, and asked myself by what right this informal votary of form pretended to run riot through a poor charmed flâneur’s quiet contemplations, his attachment to the noblest of pleasures, his enjoyment of the loveliest of cities. The little book seemed invidious and insane, and it was when I remembered that I had been under no obligation to buy them that I checked myself in repenting of having done so.

While visiting Tuscany with the English brothers who are obsessed with travel guides, Tillman’s narrator exhibits the same dark pleasure in rejecting an experience of the city as mediated through the eyes of an author who has planted their stake in fact and certainty. She writes:

I switch from Italian grammar to a guidebook describing the streets I just walked. Alfred’s travel books remind me of cookbooks. They must be written by people with terrific imaginations who can sit down at a desk, relive their sensuous experiences, or if not relive them, fantasize wildly, then pluck words that satisfy from a storehouse of memories, a warehouse of words that match sensations. Such flights of fancy attempt to occupy the empty space of someone else’s imagination, where they’re meant to dress up an otherwise colorless existence or inflame the senses, like pornography. The descriptions don’t make me see better; they’re more like putting on 3-D glasses which perch shakily on the nose, always in danger of falling off, or are something entirely different from the object described, to be appreciated for themselves only. Which I suppose is OK and makes cookbooks and travel guides akin to science fiction. But everything sparkles too much, is too luscious or exquisite. Leaves a nasty aftertaste, like depression.

Not long after this scene the narrator admits that though she looks at the city, she cannot see it clearly. Her gaze, though scrutinizing, does not secure insight. “I don’t really see New York. Or when I see it, it’s always the same. I can’t see it. Or for that matter America. Just the way I don’t see Paris. Or Europe. It’s inaccessible to tourism, or it’s all tourism.” From her point of view, “everything reveals and conceals at the same time.” The parameters of the self are constantly being renegotiated by the places through which she drifts, barring her from arriving at a total, unmediated understanding of her past and the effect her father’s death—his irremediable absence—has on her relationships with the other characters in the novel.

Motion Sickness’ narrator is the missing link in a large network of characters whose lives intersect through coincidence, reinforcing the sense of the narrator as a Baudelarian existentialist detective: she is simultaneously a relayer and surveyor of information. While reflecting on her condition as a character in a novel—an extension of her literature sickness—she writes: “Virginia Woolf wrote that books continue each other and it seems to me that people continue each other too, spring ungodlike out of the heads and bodies of others, not cloned but continuities, with ties that bind, loosely or closely.” If we were to dig a little further—to excavate the novel’s matter in the Benjaminian sense (since Benjamin is a writer whose work enhances our understanding of both Tillman and James)—and more carefully examine James’ presence in Motion Sickness, the other side of the coin bearing the face of coincidence would emerge. What is revealed to us through such an excavation is an almost exact correspondence between Henry James and Lynne Tillman: like Tillman, James, who ushered in the “stream of consciousness” movement, almost exclusively explored his characters in their relations and, like her, he was a writer of ideas. Consciousness for him occurred among a network of people, places, and things—in the liminal space between bodies and objects—so much so that often, especially when reading novels from his late period, one can’t always tell who is doing the speaking and who is doing the thinking. The style is oblique, dense, layered and one perceives the material conditions of the realities being described as if through a mist—the mist of a mind transmitting his or her perceptions through language. While Tillman’s style is limpid and declarative by comparison, both writers layer their characters’ memories and interiority over the physicality of space; the outcome of their characters’ interactions is, to a certain extent, determined by the spaces they inhabit. The two writers, born respectively in 1843 and 1947—four years short of a century apart—are “uncommunicating communicators,” or what I like to think of as troubled realists, linguistic deterritorializers, excavators of literary matter.

THE GARDEN OF FORKING PATHS: MANY PATHS FOR THE NOVEL

What literature-sick novels aim to examine is the various intersections between identity and reality and the infinite number of combinations that exist between our inward and outward states; they seek to expose the hazy, tangled web that we both weave and that has been woven for us by history, and to iron out the fabric stitched together from the many threads of our material conditions (our lot in life) and our ever-shifting internal condition (our mutable inner atmosphere). But what is at stake here? Why go on about literature sickness?

The understanding I have come to is that by tracing the history of novels that are about other novels we are also tracing the history of the form and, therefore, in a position to challenge the false belief that the successful novel comes in two shapes: novels that employ lyrical realism with the aim to sculpt order out of the chaos of being and that affirm language’s ability to exist in perfect correspondence with the self; and novels that, due to their relative opacity, we might locate in the liminal spaces between perception and reality and that, in their very obsession with language and literature, reveal their doubts about the medium’s ability to accurately record the sum total of a life. If these were our only two options, we would be left with a field divided into two antagonistic camps: lyrical realism with its accompanying belief that, handled by a master, language can expose the various facets of existence with precision and allow us to overcome the elusive nature of life, and the supposed anti-realism of the psychological novel that questions our ability to climb the ladder of language toward transcendence precisely because such novels locate consciousness everywhere and nowhere at once. While novels about literature sickness are more likely to fall in the latter camp, they are not exclusive to it. Nor does intelligent literature ever fall squarely into this or that camp. I’d like to borrow here from Henry James’ famous preface to The Portrait of a Lady (the very first novel we witness the narrator of Motion Sickness reading), in which he writes: “The house of fiction has in short not one window, but a million—a number of possible windows not to be reckoned, rather; every one of which has been pierced, or is still pierceable, in its vast front, by the need of the individual vision and by the pressure of the individual will.”

The garden of literature is full of forking paths. The novel is alive. It is constantly evolving. If it were to cease to evolve, it would have an expiration date. But it doesn’t. Those who fear the death of the novel—a notion we see tossed around quite a lot these days and one that is avidly counteracted by novels featuring characters who are literature sick—are suffering from a case of misplaced anxiety. They have likely come to know the novel in only one form and this attachment, or, to put it plainly, co-dependence, blinds them to infinite future possibilities. What is revealed in the claim that the novel is dead or dying is a private anxiety: that a particular identity—often belonging to a privileged few—and the means and mediums through which such a subjectivity might relate to the world, are not the only ones out there—that there is no such thing as an absolute common experience. Who gets to write the great American novel? Lynne Tillman has written novels that are both great—epic in scale—and utterly American. And yet none of her books have been referred to as a “Great American novel.” She, herself, finds the very notion laughable. But her novels are great in the sense that they are generous and serious and funny; they are not schematic or stagnant; they do not attempt to organize our experience of reality, thereby reassuring us of our inherent goodness. Most importantly, her books do not slyly suggest that we can attain mastery over reality. Because were we able to do so, what we would be affirming is a fantasy of control often allowed only to those who are privileged enough not to have suffered the cruelties of history.

The question of reality, then, is also a question of identity. Just as reality consists of multiple intersecting planes that are often contradictory, so too does identity. In the words of James Baldwin, “the person cannot be considered apart from the forces that have produced her.” It follows then, that if we believe that a novel should look like this or like that, we are also accidentally asking to “consider the person apart from the forces that have produced her.” If we want to remain open and if we want to keep our ear to the ground, we cannot create a condition in which only a select few are allowed to be our messengers. We cannot insist on one or two forms for the novel. Such an insistence is blind to the rich and mercurial history of the form, just as it is blind to the myriad bodies and psyches that have stories to tell—stories that have different shapes and that, in order to maintain their integrity and to remain honest, must find their own forms. We cannot establish parameters around what a novel can or cannot be, unless we are also willing, in James’ words, to “bring it down from its large, free character of an immense and exquisite correspondence with life.” Or, to draw from his essays on The Art of Fiction, “The only obligation to which in advance we may hold a novel without incurring the accusation of being arbitrary, is that it be interesting. That general responsibility rests upon it, but it is the only one I can think of. The ways in which it is at liberty to accomplish this result strike me as innumerable and such as can only suffer from being marked out, or fenced in, by prescription. They are as various as the temperament of man, and they are successful in proportion as they reveal a particular mind, different from others.” The novel, left to its own devices, is capable of regenerating. And novels that are self-consciously about other novels feed on the history of literature to do so. They are a record of change in motion and therefore harbor transformational powers precisely because those who pen them are unafraid to plunge headfirst into the residue of history—the history of man and the history of the form—a practice those of us who prefer to prematurely cordon off and define the novel may shy away from at the expense of living with one eye closed.

Purchase a copy of the current issue of The Believer here, and subscribe today to receive the next six issues for $48.