I.

My parents raised me in a white-sided saltbox house, the sort children draw in crayon. Years before we lived there, it had been cut in half and moved across town. We never learned why.

II.

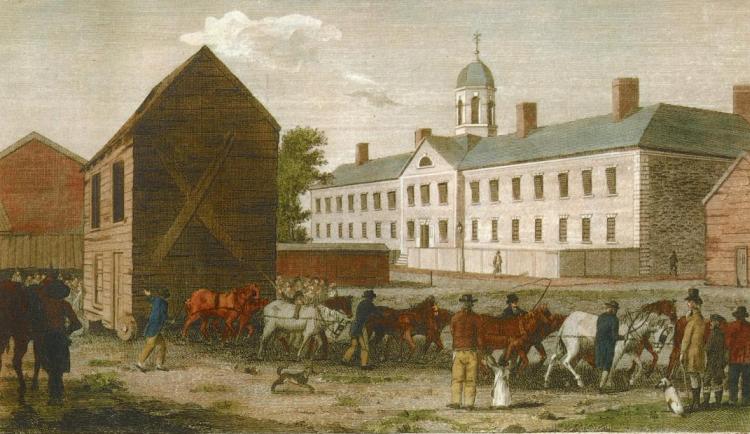

In the days of candles and outhouses, Americans lifted and moved countless houses. To raze an old house and build a new one proved more costly and difficult than laying it on logs and pulling it through unpaved streets by horse or oxen. A 1799 engraving by William Birch and Son reveals a team of horses pulling a saltbox structure attached to wooden wheels through Philadelphia’s Walnut Street. Since then, Americans have moved lighthouses, churches, hotels, theaters, even an airport terminal.

Today Americans move fewer houses. Breaking off and hauling walls and roofs to a landfill is easier, and often cheaper, than recycling a house. Even simpler: demolition. YouTube is full of instructional videos: “How to demolish a house in 20 minutes! [Part I],” “How to Demolish a House in 3 Minutes,” “How To Demolish a House With Case Excavator,” and “Rednecks Blow Up House With Cannon.”

“I wish the city would buy and demolish it,” my mom tells me of her home in Ohio, the house where I was raised. “The land is worth more than these walls.”

The living room wall is cracked, as is the wall of my childhood bedroom above it, indicating where movers had cut the house in half. We never could hang a picture straight because the movers left the house uneven. That’s why as a child, when I drew landscapes, I started with a crooked horizon. My parents corrected our wobbling tables and chairs by slipping coasters and blocks of wood underneath one side of our furniture. Friends called the house “tiny,” but in my mind it rivaled the castles in my children’s books—back when my dad was still alive.

Our garage was his magician’s hat. My mom helped him carry out new, amazing objects: bookshelves taller than them, rose arches, birdhouses with as many as eight different entrances, dollhouses shaped like our house. Too enormous to fit through our back door, my favorite dollhouse required him to remove the door from its hinges. In the summer months, the dollhouse stayed outside. One day he mounted it on wheels.

“A mobile home,” he called it.

The roof, made of real asphalt like ours, lifted off to reveal an attic. He screened the windows and added shutters. He wallpapered each room. He used free samples of linoleum and carpet from a local flooring store; the saleswoman assumed we were redecorating our house. He even made a staircase and cut a hole in the second floor.

“I don’t want to make your dolls have to fly from floor to floor,” he said.

In the days after his death, I knelt in front of the dollhouse—then stored in our garage—and talked to it, as if he’d transformed into it. I was eighteen and home from college, a school just outside Chicago. He was eighty and had died on a borrowed bed from hospice, next to the crack in the living room wall.

“When I die,” my mom said after his funeral, “do what you want with this place.”

A few days later, I boarded a train and left “this place” for Chicago.

III.

In the nineteenth-century, Chicago transformed house moving into an industry.

But first, the Indians would be forced to move their homes.

Shortly after the Village of Chicago became incorporated in 1833, some white Christian politicians decided that five million acres of wigwams and wooden lodges—which reached from the Rock River in Illinois to the Grand River in Michigan—belonged to the American government. The Potawatomi Indians refused to sell their land and move. They already had sold off other land in the 1822 Treaty of Chicago. Chief Metea had said back then: “We have sold you a great tract of land already; but it is not enough! We sold it to you for the benefit of your children, to farm and to live upon. We have now but little left. We shall want it all for ourselves. We know not how long we may live, and we wish to have some lands for our children to hunt upon. You are gradually taking away our hunting-grounds. Your children are driving us before them. We are growing uneasy. What lands you have, you may retain forever; but we shall sell no more.” But the Indians reluctantly would sell again. Pressured to accept food, whiskey, and cash, they signed the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, agreeing to move west of the Mississippi River within the next two years. The wigwams and wooden lodges would be replaced with thousands of new homes for white people. White men would become rich moving them.

Early movers, such as Chester Tupper, Chicago’s first professional house mover, shied from shanties, log cabins, and brick or stone buildings, but balloon frame structures could be lifted and rolled down streets relatively easily. Born in Missouri in the eighteenth century yet called “Chicago construction” in the nineteenth, balloon framing required lumber, nails, and basic carpentry skills. Lightweight, sturdy, and flexible, a balloon frame structure could be built within a week. Tupper moved thousands of them on rollers.

In his memoir, A Pioneer in Northwest America, 1841-1858, the pioneer and priest Gustaf Unonius wrote about seeing Chicago houses moved: “I have seen houses on the move while the families living in them continued with their daily tasks, keeping fire in the stove, eating their meals as usual, and at night quietly going to bed to wake up the next morning on some other street. Once a house passed my window while a tavern business housed in it went on as usual. Even churches have been transported in this fashion, but as far as I know, never with services going on.”

The practice, however, became such a nuisance that Chicago city council decreed, in 1846, that no more than one building could stand in the streets of any block at the same time, and no building could stand in the streets for more than three days.

My dollhouse moved so much—between our living room, our driveway, our back porch, and my playhouse in the backyard—that it could have been a nuisance, but my dad never treated it as such. When I eventually lost interest in my dolls, we moved the dollhouse into the garage and covered it with a tarp. After he died, I had dreams about us moving it. In one, I watched as he removed our back door from its hinges so that the dollhouse could go outside. “But it’s winter, Dad,” I told him.

The dream must have been about his dead body. At his funeral, my mom had told me that the hard winter ground needed to break before he could be buried. In the dream, his dead body was the dollhouse that he was trying to move outside. I wanted it in our living room. I wanted him living in our house forever. But he wanted me to let him go, to let him be dead. Could the interpretation be that simple?

Away at college, I could pretend he still lived inside our uneven house.

I tried not to remember his uneven breathing.

IV.

House moving, as disruptive as it could be, ultimately rescued the city. By 1855, Chicago’s water supply was causing cholera and dysentery epidemics. Because the city was flat and low—only about two feet above the river level—sewage would drain off into the Chicago River, which flowed into Lake Michigan, the city’s source of drinking water. To save the drinking water and avoid becoming a swamp, Chicago needed a comprehensive city-wide sewerage system. Ellis Chesbrough, a self-trained engineer who designed Boston’s water distribution system, developed a plan to create artificial water flow by raising Chicago’s street level by ten feet. The sewerage system would be built above ground, and then all the buildings would be raised using jack screws and reattached to the ground. George Pullman, the famous railroad man, also moved to Chicago to help raise the buildings and construct new foundations underneath. He even helped raise a six-story brick hotel while the guests remained inside. Less than a decade later, he would invent the sleeper car, what he called a “hotel on wheels.”

“House moving is occasionally to be seen in other parts of America,” David Macrae, a visitor to Chicago, wrote of his stay in 1868, “but Chicago, owing to its circumstances, has been the great nursery-ground and arena for it. Even there it will become less common by-and-by, as the city is now for the most part graded, and new houses are built on the new level. But house moving is only one of the wonders of that great city.”

Then the Great Fire of 1871 hit.

My sophomore year of college, I studied the Great Fire in a class called Development of the Modern American City. At my midterm exam, as I stared at the blank page where I was to write about the Great Fire, I repeated three-three-three to myself: three hundred people died and 3.3 square miles of Chicago were destroyed. Chicago depended on houses, sidewalks, and roads made of wood. A drought had hit before the fire. Add strong winds and you have the 1871 tragedy.

But every time I pressed my pen to the exam, a skyline of burning dollhouses appeared on the page. Suddenly the midterm became about my dollhouse and whether it was on fire right then: What if the fire spreads from our garage to our house when my mom is asleep? “I shouldn’t be here,” I wrote on my exam. “I should be with her.”

“Jeannie, Jeannie, Jeannie,” I suddenly heard being hissed.

I looked around; no one was looking at me.

I stood, sat, stood.

I was inside a big ringing bell. Or was I hearing fire sirens?

The other students were in a classroom, writing about a fire.

I walked outside into the cold. The teaching assistant followed.

“What’s going on?” she asked.

I paced, sat on the grass, stood, paced some more.

“Fail me,” I said.

“Let’s go see the professor,” she said gently.

As she walked me to his office, I almost said: my dad died. But one year had passed since then.

“I studied,” I assured my professor as his assistant left the room. “I’m sorry.”

For the next hour, my professor asked me about myself. I was from Ohio, I said. He too was from Ohio. I said I was studying journalism, but that I also wanted to study poetry and fiction.

“How about you write a paper for me,” he said, “and forget the exam. What do you say?”

I thanked him and rushed to the library, pacing through the stacks. I had no idea how to stop moving.

V.

After the Great Fire of 1871, an argument against wooden house construction arose. Chicago city council passed a compromise that blocked the relocation of wooden buildings in only a few districts. Also, wood-frame structures could no longer be built in the center of the city. Lower-income tenements were pushed to Chicago’s outskirts. From then on, all new buildings were advertised as absolutely fireproof.

And so house moving continued to thrive. By the 1880s, some Chicago streets encountered weeks-long traffic delays due to parked houses. Even streetcar service faced interruptions due to houses stuck on the tracks. Common among the working class, balloon frame houses—“tramp houses,” as one newspaper called them—endangered property values when placed next to expensive residences. In 1883, city council revised the building code, requiring house movers to apply for licenses, take out a ten-thousand-dollar bond, and pay a five-dollar permit fee per move. Among the new rules, houses could only enter neighborhoods where current property owners approved. Nonetheless, from 1884 to 1890, the number of cleared permits climbed from 726 to 1,710.

Chicago’s developing transportation system soon became a literal roadblock for house movers. Overhead electric trolley lines replaced cable cars, prompting some enterprising movers to cut the wires. City officials—previously unsympathetic toward movers—ordered streetcar companies to raise wires to accommodate tall buildings. But once the elevated rail system emerged in 1891, followed by the elevation of steam railway tracks soon after the turn of the century, the number of relocations dwindled.

Still, movers persisted.

They loaded a few large buildings onto barges and carried them over the Chicago River or Lake Michigan for part of the journey. Some movers even convinced the city to allow them to move houses with the help of the elevated L tracks.

By my third year of college, I was riding the L aimlessly for entire days, not wanting to explain my relentless crying to other students. I could say the words “my dad died,” but I was afraid of answering “when?” Why should when matter?, I would think as the Chicago skyline passed me by. Had he been in pain? He never complained. He winced once; he was in bed, and I was standing by the crack in the wall, but he didn’t know I was there.

On the L train, I drafted a short story about a teenager whose father had died. A week after his funeral, she and her mother move into a trailer hitched to a hunk of concrete six feet below ground.

Trailer people call that a dead man, the teenage narrator explains to the reader. I suppose it secures you someplace, makes it harder to move.

Later I would research mobile homes, making lists of their beautiful names: New Moon, Silver Crest, Skyline, Golden West. I expanded the story into a novella that summer, but by spring of my senior year—frustrated by my inability to articulate how much I loved my dad—I deleted everything except my grief.

VI.

By the twentieth century, power lines and municipal permits interfered, and houses in Chicago mostly stopped moving. In 1977 the city’s oldest surviving house, built in 1836 for Henry B. Clarke, was lifted twenty-seven feet into the air on wooden cribs and pulled across the 44th Street L tracks. Having already been moved once (in 1872), the Clarke house was now returning one block away from its original property. Despite the 16-degree weather, about two thousand Chicagoans gathered to watch as the 120-ton Gothic Revival clapboard house left the tracks and reached a different set of cribs on the other side. Unfortunately for the movers, the hydraulic equipment froze and the house remained in the air for two weeks. As L trains rushed by, their passengers could glimpse it outside their windows.

The Henry B. Clarke house—moved and then moved again, only to return to where it started—reminds me of what Chief Metea told the white politicians: “You are never satisfied!”

When I was a child, my parents and I sometimes toured open houses, searching for a bigger, newer house. But then we would come home to our rose arches and birdhouses, my playhouse, the fence around my small garden and the fence around our large yard—all built by my dad. He even built a fence on wheels that went across our driveway. I doubt we would have had much of this at a new house. My dad was in his sixties when I was born. He would not be fashioning such things out of scrap wood forever, and I think he knew that. “I love it here,” he often said when we came home from visiting other houses. Half-joking, he once told my mom, “After I die, bury me in the back yard.”

I’m no longer interested in why my house was ever moved. For a while I shifted to researching the houses where my dad had lived before I was born. He was from New York, and after college graduation I moved there. But by the time I tried to visit his first house, it was an empty plot of land. The house where he spent his early adult years caught fire the same day I arranged to visit. But I’m leaving that last detail alone for now. If I think about it for too long, I see it as a sign. And I’m supposed to be done with those.

I spent my twenties in and out of psychiatric wards. My diagnoses shifted between schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder, illnesses that conjure images of my uneven house. And the split-in-half feeling keeps moving with me: Ohio, Chicago, New York, it doesn’t matter where.

“I hope someone buys it,” my mom says of her house, finally, officially, for sale. “I hate this place. I can’t take care of it anymore. When your dad was here—”

“I know.”

The dollhouse is collecting dust in her garage. The exterior needs new paint. The windows need new screens. The roof has started to fade.

It hasn’t been moved in probably twenty years.

I try to remember the arrangement of the rooms. The staircase always stayed where it was, underneath a hole between the first and second floors. The kitchen went on the first floor because that’s where my dad installed the linoleum. The second and third floors he carpeted.

“Where should the living room go?” I asked him.

“If we put an area rug on the first floor,” he told me, “the living room could go off the kitchen.”

So he made an area rug. The second floor became the daughter’s bedroom. The top floor is where her parents slept. But usually the parents and the daughter stayed together on the first floor.

Lifting off the roof revealed the attic where the daughter stored her toys, but I pretended she was too mature for those. The dollhouse was about pretending.

Not being in Ohio, I sometimes pretend he’s still alive. The dollhouse is proof he existed, proof he’s no longer here—and I don’t want it moved. Not yet.