Well 99 years is a long, long, long time

99 years is such a long, long, long time

99 years is a long, long time

Well look at me, I’ll never be free

I’m a long time woman

—Pam Grier, “Long Time Woman”

Tuesday was Pam Grier’s birthday; she turned seventy-one. Tuesday was a hard day. Tuesday was a birthday and a deathday, a day I felt both grateful to be alive and aware that I was grateful to be alive. Tuesday was a collage, a la Romare Bearden; or a postmodern painting by Emma Amos, who passed away last weekend. The day was a mixed media amalgamation layered with dreams, nightmares, songs, moods, movies, and the shows I binge on my streaming devices. Tuesday, half of the time I spent online, I spent grieving. The other half I was thinking about the transcendence and timeliness of art. I saw beautiful photos of Pam Grier on my Instagram timeline, and I admired her life and badass persona through the years. Every other picture was Pam Grier, in some karate power pose, in her flight attendant getup from Jackie Brown, looking shrewd and worried. Every other picture was a yearbook photo of Ahmaud Arbery, or cellphone footage of Amy Cooper, the white woman who falsely accused Christian Cooper, a black bird-watcher, of threatening her and her dog; or video of George Floyd’s death; or a still of a white police officer with his knee on Floyd’s neck.

In the articles I read about Amy Cooper’s punishment and public shaming, I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry whenever journalists clarified that she was not related to Christian, the black man who she could have easily killed when she called the cops on him. When I visited my favorite trashy celebrity gossip site for relief, I was reminded that Doja Cat, an artist whose hit “Say So” just dropped to number two on the Billboard chart, is facing backlash. “Dindu Nuffin,” a song she released in 2015, and whose title is a racist slur used to mock victims of police brutality, has recently resurfaced. No matter how fast I scroll past death footage I do not want to see, and won’t play, the fear of being unjustly murdered remains inside my mind like a jammed VHS tape, or, to update the reference to a format I avoid like the plague because it’s used to spread death gifs and racism, an endlessly looping Tiktok clip. It’s in me. I spent half the day stuck like that, like an old tape, like a new loop, on my couch, not watching TV—working, thinking, eating—reeling. I am exhausted. But because I am me, I escape these hard feelings by distraction: by working, thinking, watching TV. Tuesday, I went to a food co-op, came home, sat myself down, and purposely avoided the news so I did not have to watch a montage of Arbery, Floyd, Cooper, and Breonna Taylor—in other words, myself—and opted for something fictional. I took a CBD capsule and put on Jackie Brown. I hope that I have not gone entirely numb.

One thing I’ve learned about myself during quarantine: I engage with some art much like a holistic health devotee gulps burning oregano oil. I realize I’m an aspirational viewer. Sometimes I read and watch stuff for the same reason Zadie Smith has said that she writes about divorce and other issues: to proactively deal with complicated emotions. In an interview with The Atlantic, Smith said, “To put it simply, fiction is like a hypothetical area in which to act. That’s what Aristotle thought—that fictional narrative was a place to imagine what you would do in this, that, or the other situation.”

As someone who primarily works as a critic, the moment of reading and watching moving images provides a similar experience for me. Criticism is my “hypothetical area.” By intellectually engaging with whatever I’m afraid of, I feel the feelings and get over the fear, freeing myself to live a different outcome. I’m turning thirty-one soon, so I’m more attuned to my age, and not only the small physical changes I’ve noticed. I’m aware of the competing forces of hope, numbness, and despair that live inside of me. I struggle to talk about my pain as a black woman, and as a person who is hypersensitive to violence. Nor do I really want to right now. I can’t—and won’t—articulate what it means to have actually seen a loved one’s last minutes on earth, as I have. The pain is too delicate to explain more precisely, too deeply felt to phrase without sentimentalizing it and containing what is capacious and multifaceted into maudlin language that compresses big emotions into a meme. In the introduction to her 1997 book Scenes of Subjection, Saidiya Hartman, explains why she will not recreate the beating of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester, and her subsequent expression of pain, which he includes in his autobiography:

I have chosen not to reproduce Douglass’s account of the beating of Aunt Hester in order to call attention to the ease with which such scenes are usually reiterated, the casualness with which they are circulated, and the consequences of the routine display of the slave’s ravaged body.”

The routine “spectacular character of black suffering” in these accounts creates a condition Hartman calls “hypervisibility.” In Fred Moten’s response to Hartman’s gesture, “Resistance of the Object: Aunt Hester’s Scream,” he writes, “The history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist.” He then details the comportment of Hartman’s critique both on and off the page. He writes:

Between looking and being looked at, spectacle and spectatorship, enjoyment and being enjoyed, lies and moves the economy of what Hartman calls hypervisibility. She allows and demands an investigation of this hypervisibility in its relation to a certain musical obscurity and opens us to the problematics of everyday ritual, the stagedness of the violently (and sometimes amelioratively) quotidian, the essential drama of black life, as Zora Neale Hurston might say.

In this violently quotidian moment, I notice a link between my coping mechanisms of mind-numbing distraction and aspirational viewing: amid the continued devaluation of black life in this country, when black people are dying disproportionately from COVID-19 and police brutality, distraction has become both a carefully-nursed desire and a requirement just to get through the days. And it’s something I’ve gotten better at as I age. In 2013, when George Zimmerman got off, I cried hysterically; now, I don’t have it in me anymore. As Stephen Jackson, a close friend of George Floyd explained at a press conference on Friday, “I don’t have no more tears, honestly. I’ve cried enough. I’ve cried enough.” I’m in a similar place; I don’t have a lot of tears left. I do, however, have a birthday coming up tomorrow, and I wonder what it means for me to be done crying, despite what I hope are many more years to come?

I will not perform my grief on the page, even though I wish I could literalize it in tears, and even though the page has long been my savior. Instead of trying—and failing—to say how much all of this means to me, I will do what has helped my brain protect me. I’ll tell you about some things I watched on TV. In responding to the drama of my life, I go first to comedy.

After Jackie Brown, I played an episode of the FX show Better Things. I might have a hard time crying, but I love laughing, and this show is really funny. On Tuesday night, I learned that the series was renewed for a fifth season, which means I have another thing to look forward to. Binge-watching all forty-two episodes of Better Things during quarantine has helped me pass free time without completely turning off my brain. Better Things, co-created by and starring Pamela Adlon, concerns the life of Angeleno Sam Fox (Adlon), a fifty-something character actor and single mother of three daughters. I love its direction (which is mostly done by Adlon), its music supervision, its vignette style, its depiction of friendship among women, and its verisimilitude, but I recognize another reason I enjoy the show. I close-read Better Things as a thirty year-old for the same reason I devoured, in middle school, the adventures of older teens in Moesha, The O.C., That’s So Raven, and Gilmore Girls; and for the same reason I couldn’t get enough of Smith’s campus novels and polyphonic explorations of life after thirty in my late teens and early twenties. I watch them to get a sense of what might happen to me. Like Raven Baxter, a role model for my goofy twelve year-old self, I can’t stop gazing into the future, wanting to preempt what might meet me there. That’s a long-winded way to say I appreciate the show’s depiction of aging, and all that comes with it. One day, I look forward to being as comfortable in my skin as Sam and her friends.

On the surface Sam and I are pretty dissimilar: she’s twenty years older than I am; she’s an actor, I’m a writer; she has children, I don’t yet; she owns her home (and an adjoining one her mother lives in), while I’m still paying rent on my iPhone; I don’t need to point out that she’s white. But in some ways, we’re a lot alike. We both: produce art for a living; work in fields that are extremely insular; constantly negotiate power and influence; are sometimes self-righteous about being single; care for our mothers; and have issues with our joints. Sam consistently wears a hand brace, and I sprain my ankles more than I care to admit. Last Thursday, I rolled my right ankle walking down a short flight of stairs outside my mom’s duplex as I rushed to get some quarantine exercise. Later, I went to Target and bought a compression sleeve, which I’ve worn for the better part of a week.

In the opening segment of “Eulogy,” a second season episode, Sam’s teaching an acting class. She totally gives off the cool that comes with not giving a shit, the implacable mien that comes with living long enough to really get it, you know? As she critiques the scene work of her middling students, who are doing their best to make clichéd breakup lines feel authentic, Sam delivers the kind of sly, metatextual spiel that’s both real dialogue and art critique. Here she is honing in on a particularly bad line in the script, delivered by the jilted boyfriend:

Ok, so when he says “I’m not perfect,” what is that? Why does he say that? Why? Because this is shitty writing, that’s why. That’s the only reason. But look, most of the work you’re gonna be given as actors, it’s gonna be shitty writing. Do you think you’re gonna walk out of here and get a job doing a Tarantino monologue, like straight out of the gate? No. At best, ninety percent of the words that you’re gonna read are gonna suck and have no real feeling behind it. Anyone can do a scene that’s well-written. The skill you’re gonna need if you wanna really work and get steady work—as steady as you can anyway—is to make shitty writing mean something. To “elevate the work.” If you can take a bad script and make it work, they’ll keep hiring you.

Throughout many of Better Things’s episodes, we see Sam elevating the work she’s given: car commercials, big-budget monster movies, and somewhat pretentious avant-garde Broadway fare. Louis C.K. wrote that acting monologue, and the episode it appears in. In season one’s “Alarms,” an episode co-written by Adlon and C.K., Adlon elevates the material she’s given, turning a scene of an acting colleague asking if he can pull his dick out into a tableau of banal horror. In the show’s third season, in episodes “Monsters in the Moonlight” and “Show Me the Magic,” Sam and her cohort of forty- and fifty-something actresses and showbiz veterans gather at the home of Lala (Judy Reyes) to catch up, get high, and collectively process their lives, including the dawning invisibility they feel. They bond over the ways they’re disregarded as middle-aged women (or at least what Hollywood considers middle-aged). Then Lala’s husband comes home, enters the conversation, and ruins it by asking, mockingly, if the women are having “girl talk,” i.e. a garden-variety chat about sex. Better Things makes clear that with age comes a kind of wizened numbness, especially when your life involves dealing with dicks. The hopefulness of its title manifests in the modicum of progress each of its characters makes. I watch Better Things with the hope that even if things don’t get better, I will find a way to make due.

In August 2011, when I was twenty two, my partner at the time—a black man—and I drove his parents’ Camry Hybrid from Philadelphia to Houston, Texas, to check out the University of Houston where I was thinking about applying to grad school. We spent a few days in the city, doing something each of us loved—eating at its vegan restaurants (for me), and looking for skateparks (for him). At the end of our Houston trip, we ventured up to Arlington, Texas, where I’d spent a few of my childhood years. We stopped at my old apartment complex, went to the Parks Mall, where my parents had both worked and where I spent formative moments roaming, and hit the road. On our way north, the police stopped us three times in one hour. The first time, we were exiting a gas station and my partner made an “illegal” left out of the parking lot. We heard the siren immediately. After a series of questions about what was in our car, we were issued a ticket. Once we hit the highway, we were stopped a second time, apparently for a busted taillight, and this time the questions were compounded.

You have Pennsylvania tags. Why are you in Texas?

What’s in the trunk?

If I search the car am I going to find drugs?

You sure?

You’re not lying to me, are you?

Even though we explained why we were in Texas—for the reasons I’ve mentioned—we were separated. My partner was placed in the back of a police car, and a cop came to the passenger’s side, where I was sitting, to interrogate me. I was so nervous it’s no wonder I didn’t pee on myself. Stuttering, my hands shaking but intentionally placed in plain sight, I went into detail about the day we’d just had with an escalating attention to the granularity of each moment of the last twelve hours: where we went, how long we spent at each place, what we ate, the pulls of the University of Houston’s Doctoral Program in Creative Writing (Donald Barthelme, Mat Johnson). Who knows what stopped the interrogation—the consistency of the stories, the detail of my recap—but eventually they relented and let us go with a warning about the taillight. After it was over I was humiliated. I was embarrassed by my simping language—“Yes, sir,” “Would you like to see our food court receipt, officer?”—for sounding like someone I was naive enough to be ashamed by. In a millisecond, I’d transformed in to the sort of beleaguered black person in dramas about slavery and the Civil Rights movement that made me angry. I was upset with myself for capitulating, and later, I was annoyed at myself for not understanding the truth in those depictions I’d hated. I cried nonstop and babbled for the next moment, not really believing what had happened, even though I knew, logically, that this kind of thing happens all the time, happened in Philly all the time. When we were stopped for the third time I shut down completely. I don’t think I said anything. Being stopped three times in an hour, an event that’s in theory as absurd as a Barthelme story but in lived experience wasn’t, made me feel instantly older. Frantically crying, I told my partner that I didn’t want to—wouldn’t—drive any longer. We pulled off the road and bought Pizza Hut before stopping at a motel. The fact that it was Pizza Hut is inconsequential, but it’s the kind of detail I recount now, as I did then, because I still find myself wanting to testify to the detail of what happened. I still want to act as a witness to myself. Why write this out? By writing it have I turned it into a spectacle? I’ve questioned my desire to publicize this experience over the course of the days I’ve spent drafting this essay. The truth is, I’ve wanted to write about this experience since it happened, but haven’t had the energy to psychically retrace my steps, so to speak. It’s strange and unsettling to me that, in light of the events of the past week, I have given myself license to write this, to bear witness to it.

Pam Grier has had a career that both mirrors and diverges from Sam Fox’s somewhat steady acting trajectory. Grier, like the new actors in Sam’s class, did not get a job doing a Tarantino-esque monologue out of the gate. Over the course of a fifty year tenure, Grier has been a box office star and, in later years, as she’s aged and become less desirable by Hollywood’s standards, a kind of character actor, guest starring on procedurals, popping up in straight-to-streaming flicks, and hamming it up as a late-blooming scream queen. She made her bones as a Blaxploitation superstar, and was not above appearing in the dreadful Bones, as the ex-wife of a vengeful ghost pimp. I appreciate her range, and the fact that, like, getting great opportunities into one’s fifties and beyond is not a privilege every working woman artist can enjoy. It’s something I can relate to in my work as a freelance writer; the quality of assignments vary, and sometimes you say yes to things you might not otherwise do because you’ve got to pay bills.

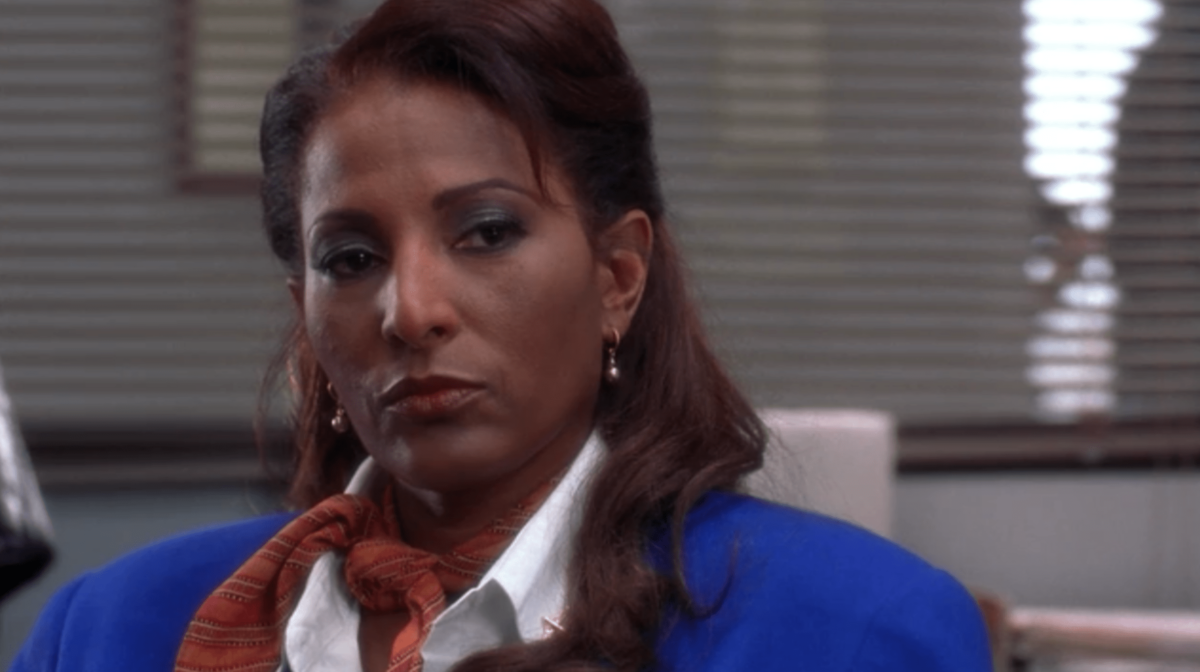

Nothing highlights Grier’s dynamism and ingenuity more than her turn in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown (1997), where both she and her character’s professional instability raise the film’s stakes. Grier plays the namesake lady, who, in the words of the LAPD detective investigating her, is a “forty-four year-old black woman” who “didn’t exactly set the world on fire.” (The phrase “forty-four year-old black woman” appears four times in the first thirty-nine minutes of the film, and is uniformly spoken by men.) Trafficking small amounts of cocaine and working as a stewardess for budget airline Cabo Air, Jackie is at her wit’s end, and an easy target for both LAPD and ATF cops. Despite her expendability within her profession, Jackie is hypervisible—to use Hartman’s term—in a way that her beach bunny associate Melanie (Bridget Fonda) simply isn’t. She spends the movie using her ingenuity, tactical mind, and instincts to outsmart the career criminals in her midst. Counteracting “The Man” and the men who are out to exploit her one way or another, Jackie takes lemons and makes a whisky sour, plotting while she drinks at a Hawthorne, California after hours spot.

Jackie Brown is celebrated for being a smart update on the kinds of films (Coffy, Foxy Brown, Black Mama White Mama) that made Grier famous. An adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s 1992 novel Rum Punch, Jackie is a clever inversion of the average crime bro noir and the Blaxploitation genre, highlighting the gendered poignance of the clichéd “one last score” premise. As David Roche writes in Quentin Tarantino: Poetics and Politics of Cinematic Metafiction, “Jackie Brown relates the story of Jackie’s attempt to gain some control over her life in spite of her body.” Here, Grier’s Brown participates in one last score, in what, to some, might be considered her last fuckable year.

Although Tarantino’s script is great, in Jackie Brown, it is Grier who saves her career by putting together one of the most moving performances of resigned resourcefulness I’ve ever seen onscreen. She elevates the work, inverting the figure of the black power dominatrix, the kind of character that brought her global fame, into something more complicated, sophisticated, and more worn down. Obviously, Foxy Brown is a fantasy, a wet dream of female empowerment. In it, Grier makes kicking racist ass look fun. In Jackie Brown, she wears grief, and the daily torment of battling malaise, with the lived-in resignation of Jackie’s slightly-rumpled Cabo Air uniform. The Jackie character is the logical outcome of someone who has spent her youth fighting and eventually burns out. In a brilliant move, Tarantino uses his penchant for pastiche to hint, again, at this woman’s weariness. Over a scene of Jackie walking into a jail cell, the director plays a short clip of “Long Time Woman,” a song Grier recorded for the film The Big Doll House (1971), a Blaxploitation flick set in a women’s prison. “Look at me,” she sings, “I’ll never be free / I’m a long time woman.” In two of the film’s most moving scenes, Jackie is alone in her car singing, barely lip-syncing Randy Crawford’s “Street Life” and Bobby Womack’s “Across 110th St.” Part of the karaoke’s poignance resides in Grier’s response to the lyrics. When she sings, “and you better not get old… or you’re gonna feel the cold,” from “Street Life,” tiny tics of agony are expressed in a small nod, and a weary eye twitch, as if it’s the ache of time, and not the repercussions of criminal activity, that has hurt the most. In these car scenes, Jackie’s youth, cued by the ‘70s hits of her heyday, fuses with the weary Jackie of the mid-’90s. These musical cues suggest that she is truly a long time woman. She may have avoided prison, but she is still contained: by fear, by time, by the emotion welled within.

What, exactly, is a “long time woman”? The song’s second verse lays out a defining characteristic: emotional imprisonment. “I’m a long time woman / Ain’t nobody to please / Got natural feelings / Like a bad disease.”

A long time woman is long-suffering, tired, emotionally distant; she likens her “natural feelings” to a “bad disease.” The film’s denouement sets the stage for reading Jackie in this vein. Although we learn that Jackie is going to Madrid following a successful heist, there’s a sense she still hasn’t escaped from whatever’s dogging her. Even though the last time we see her she’s in a new car, driving to the airport, it still feels like she’s hit a dead end. The giveaway? In the film’s final scene, she’s holding back tears as she drives, singing “Across 110th St.” with a restraint you wouldn’t expect for someone who has seemingly prevailed, and who will presumably use the $500,000 she’s hustled to set up a more sustainable future for herself. In Jackie’s beautiful lined face, there are shades of regret and exhaustion detected in glazy wet eyes and a half-hearted sigh. I’ve always been curious about the shyness and withholding in the acting of that scene. I know that she’s tired, but it still appears that she doesn’t fully allow herself to feel even that. Of course, there are so many reasons she’s not ready to bawl. After all, she’s still in a car, which is a semi-private, semi-public space. And despite her financial windfall, she can’t get back all those years of uncertainty. They have taken a toll. As I watched this film on Tuesday, and parts of it on Thursday as Minneapolis burned, I’m bothered that I haven’t yet cried over George Floyd. I recognize Jackie’s shell, the tears that just won’t come, her fear of breaking down and of being vulnerable, even when she is her only witness. I’m afraid of further developing that kind of steely veneer.

Hartman and Moten’s scholarship inspires a slightly different reading of this scene. It occurs to me that the musicality and banality of this sequence drive home Grier’s acting arc in this film, and where she lands: in this last scene, she demonstrates her character’s resistance to being an object. Throughout the film, Jackie has taken small, intentional steps in service of moving from an object—a tool of her crime boss Ordell Robbie, a pawn of the LAPD and ATF, and even a symbol of Tarantino’s role as resurrector of cult-figures—into a subject. This scene is her last stand. By the end of the film, Jackie is such a subject that she is able to do the unexpected, and that’s resist the tears that viewers think should come. Still, as much as I admire the choices of Grier and her character, I wish I could cry. I want to live long, but I do not want to be a long time woman.

As the saying goes, things change and they stay the same. In many ways, things have gotten better since Grier recorded “Long Time Woman.” And yet the “Man” Grier’s characters fought in the 1970s is still everywhere and is maybe more insidious because he hides behind the myth of progress. As Simone Browne points out in Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, the white gaze, including those of overseers and ordinary white folks who read the “Wanted” section of antebellum newspapers, were like surveillance cameras. Today, Amy Cooper and her ilk are still surveilling us, using their gaze to reinforce racist power structures. Women, and black women in particular, continue to elevate the circumstances of our lives, which is a baseline kind of work we’re given. Sometimes we don’t live long enough to see the fruits of our labor. I thought about all of that on Tuesday.

What a week. On Thursday, I took a perverse pleasure in watching footage of black protestors responding to a thirty year-old white woman who allegedly zipped around a looted Minneapolis Target in an electric wheelchair, stabbing black people. I take half-hearted joy in seeing her being sprayed in the face with a fire extinguisher, an acute comeuppance, especially in light of the fires that have burned all across the country. I wonder if delighting in the memefication of this woman’s experience means I’m further mummifying my response to tragedy. I chuckle at the fact that she looks older than she is, and that the video has trended with #Shes30, to both shock people that she’s young, and to implicitly point out that racists are not aging and dying out, like some thought they would.

My birthday is tomorrow. God willing, I will turn thirty-one. It’s a hellish time to celebrate a birthday, especially as a black woman; we are predisposed to COVID-19, premature heart disease, and death by police brutality. (See: Sandra Bland, Breonna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, Erica Garner.) When I listen to Sam Fox and her friends talk about being invisible as they age, I think, Yes, God. I’ve experienced enough street harassment and police harassment for three lifetimes, so being ignored because of my body is not exactly unwelcome. (Instead, I dread people who matter ignoring my mind.) But maybe Sam Fox isn’t the right kind of aspirational figure for me. Maybe Jackie Brown is. I, like Jackie, might not age invisibly. The older I get, the more I ask myself if invisibility is something I want. And more importantly, is invisibility something I can realistically expect to enjoy?

Since you’re here, you probably believe, like us, that work like this should be accessible to anyone who wants to read it. That’s why the entire archive of The Believer is available online for free.

The Believer is made possible solely through the incredible support of a community or readers and writers around the world. Please consider making a donation to The Believer today. Along with receiving a deluge of gratitude from the entire team, all donors are thanked in a print issue of The Believer, and every cent helps.