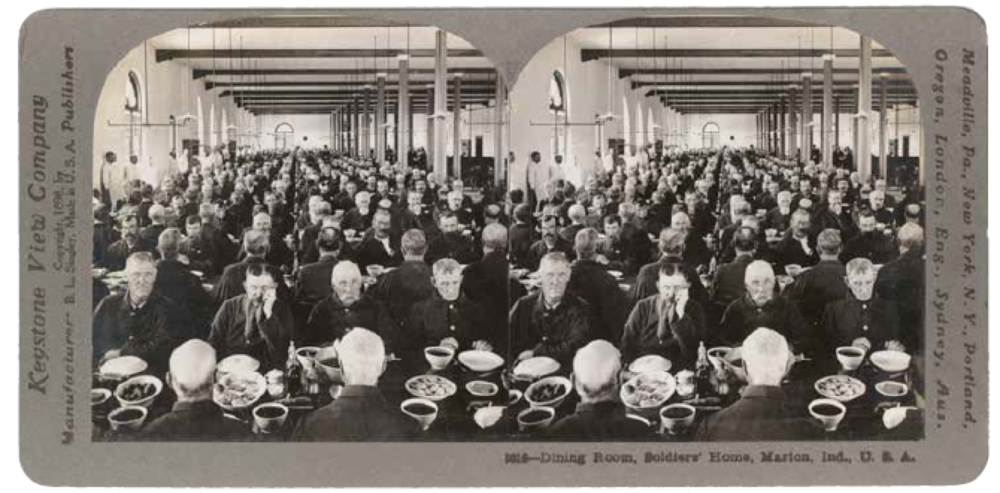

A century ago, long before the digitized high-zoot gimmickry of today’s 360-degree virtual reality headgear, and long before smartphones, the Internet, television, radio, motion pictures, and even slick news magazines, Americans by the tens of thousands distracted, enlightened, and entertained themselves with stereographs: 3-D photographs viewed in specially-designed handheld devices. Far more than merely the View-Masters of the day, stereographs—which were sold in large, beautifully-packaged sets door-to-door, or could be picked up individually in dime stores—allowed people without the necessary resources to virtually visit foreign lands. They were widely used as educational tools in school systems across the country and, before being usurped by newsreels, radio and magazines. Stereographs acted as a news outlet and offered the general public what were sometimes horrifying first-hand images of the Boxer Rebellion and the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

On the surface, and with only a cursory glance, historian, researcher and author Michael Lesy’s new book Looking Backward (published by W.W. Norton) might seem to be little more than a quaint and nostalgic coffee table collection of turn-of-the-century photographs taken around the world. But Lesy’s accompanying text, as has been the case with most of his previous books, does far more than put these stereoscopic images into their immediate context. He’s never been content just to inform readers who took a particular photo, where it was taken, and what it illustrates. Over the past forty-five years, Lesy has forged his own niche, his own singular sub-genre of literary and journalistic social criticism via archival photographs.

Since his 1973 debut, Wisconsin Death Trip, Lesy has had a knack for using photographs as a jumping-off point to weave together seemingly unconnected historical, cultural, scientific, philosophical, spiritual, literary, and personal threads. Lesy’s books make not only a coherent whole, but a whole that points toward an unexpected conclusion far beyond what lay in the pictures.

In Wisconsin Death Trip, for instance, with very little extraneous commentary, Lesy interwove a collection of news clips and photographs from local papers of the period to argue that in the waning decades of the 19th century, almost everyone who lived in Black River Falls, Wisconsin had been driven to the brink of insanity by poverty, disease, and the brutal realities of the rural Midwest. He later went on to release archival photo essays investigating everything from gangland violence in Prohibition-era Chicago to family portraits to the art of dining out in the early 20th century.

“The first book I did, which was Death Trip, came about because I was bored out of my mind,” admits Lesy, who was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2013 and currently teaches literary journalism at...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in