JR Lines

All the clichés about the Tokyo subway system (Japan Rail, or JR) are true: it is clean, quiet, wildly on time. There is no head splitting screech as the train pulls in to the station, just a silent and somehow hydraulic tension. No one talks on their cell phones in the cars, and it seemed a tacit maxim that to do so would be in terrible taste. As a New Yorker visiting Japan for the first time, I couldn’t help but become mesmerized by all this, especially given what an unrelenting shit show is the MTA subway system. Even the JR Line equivalent of New York City’s Metro Card—the green and silver “Suica” cards, which have a picture of a dancing penguin on them—are sturdier and less prone to demagnetizing breakage (and they are fun—my son’s “youth” card emitted a digitized chirp as he swiped it through, which the adult cards didn’t have). Many of the subway stations have brushed black marble floors with pixilated messages scrolling over them, orange lanterns flanking the entrances to high end shops selling beautifully packaged pastries or the latest audio gadgets. When the platform gets crowded passengers line up single file in front of each car, a practice that could not be more different from Manhattan platforms with their pile ups of bodies forcing desperate bottle necks, often with a hand or foot dangling from a door, leading an exhausted conductor to berate the packed cars through a blaring PA system. In Tokyo, even subway corridors under construction are pleasant. Where repair or renovation is in progress a taut, grey cellophane is hung around the workspace. Others have slabs of spotless canvas tied together with lengths of white rope. Only the faintest evidence of construction work could be made out behind these mysterious curtains. In one case I thought I heard whizzing, as of tiny saws or drills.

Japonaiserie

The above is, I realize, a tendentious series of comparisons, and commits the usual error of the provincial New Yorker who blithely treats Manhattan is the standard benchmark for all urban experience. However it is unavoidable for a New Yorker who has never set foot in Japan to resort to this constant Tokyo-NYC calibrating technique, and I’m afraid it will occur throughout this piece. Like many Americans (I assume) I’ve cobbled together over the years a fantasy idea of Japan through a certain kind of cultural consumerism: a childhood obsession with ninjas and ninja weaponry; the “Chiba City” of William Gibson’s Neuromancer and the Tokyo-fied sets of Blade Runner, undergraduate discovery of films by Kurasawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi, the novels of Kazuo Ishiguru, the music of Ryuichi Sakamoto (not to mention his collaborator David Sylvian’s band “Japan”), a reproduction of a Hokusai woodblock print on the cover of an LP recording of Debussy’s La Mer, a prized coffee table book of Issey Miyake designs as photographed by Irving Penn. Such a list constitutes my own private late 20th century Japonaiserie, and to have its artificial outlines soaked through with actual experience is like sunlight flooding through one of those wood-slatted interiors in Ozu’s Late Spring. Tokyo’s actual “visual density” (as Ian Buruma puts it in his memoire Tokyo Romance) is much richer and wilder than I’d imagined. You feel, when you start walking around, that you’ve time travelled a little way into the future, and actually you have. Deplaning at Haneda, fried and exhausted from the nonstop flight from JFK over the north pole, I told my son with an air of wizardry that we were “fourteen hours in the future.” I have before had to contend with the shattering of provincial preconceptions. After years of the standard teen Rimbaud fixation, arrived at via the standard portal of mid 60s Bob Dylan, I had fantasized a bohemian-moderne Paris which I pictured as somehow tinted with the iridescence of one of the prose poems from Illuminations. Arriving there for the first time in my mid-20s I immediately took the Metro to Jean-Robert Ipoustéguy’s strange bifurcated statue of Rimbaud outside the Bibliotèque de l’Arsenal. The limestone courtyard was cold and empty, the library was closed and I ended up just sitting next to the statue for awhile, somehow managing to get a chocolate stain on my back.

Food, My Allergies

A near death experience when I was a toddler involving a peanut butter and jelly sandwich led to the discovery that I have severe allergies to all peanuts, nuts and, it was later determined, fish. Anaphylactic shock results if I eat these foods, and I had it hammered into my mind (mostly by my mother) that there were deadly poisons hidden inside perfectly innocuous treats such as egg rolls (my mother had seen a news story to which she often referred that told of a child with the same allergies as mine who had eaten an egg roll in Kentucky and died). This conditioning led to a form of claustrophobia in which I am afraid of becoming trapped in a physiological process that cannot be reversed. Accordingly, I have over the years developed what might be called mild psychosomatic anaphylaxia; ie, the willful inducement of the swelling shut of my own throat. Now, everyone I spoke to about the food in Japan agreed it was heavily fish based and, according to my mother, also heavily peanut based (though this turned out to be inaccurate). As a cautionary measure I made twenty-five paper cards, each of which explained, in English, Japanese characters and transliterated Japanese, that I had very severe allergies to fish and peanuts, including oils and sauces made with fish and peanuts. I would present my cards to maître des, waiters, chefs—whoever could ensure that my food would be free of allergens. But in practice my cards were a disaster. They almost always caused confusion or generated problems that would not have existed had my first act of communication not been the presentation of these carefully made, yet, I now realize, eccentric and even slightly adversarial cards. A week into the trip my wife was begging me not to present them, and my son had taken to referring to the process as “Daddy flashing his cards.” Still, I managed to find my way around hidden fish broths and peanut oils and ended up having some of the best food I’ve ever eaten in my life. In a tiny room in the Shibuya section (roughly the equivalent of Midtown Manhattan) I had delicious yakitori chicken with a plate of grilled green peppers stuffed with meat with fresh lemon slices on them, all of which went well with the immense glass of Asahi beer they brought me. Also in Shibuya was a farmers’ market where I had a smoked goose egg on top of a charred rice ball over which a man—crouched inside a VW van with cloth embroidered menus hanging from its windows—sliced fresh pork from a skewer. As if to lash out with an extravagantly poisonous dish meant to get me back for the pain in the ass of my allergy cards, my wife ate a baby octopus whole.

Buying Books I Am Not Able to Read and Their Packaging

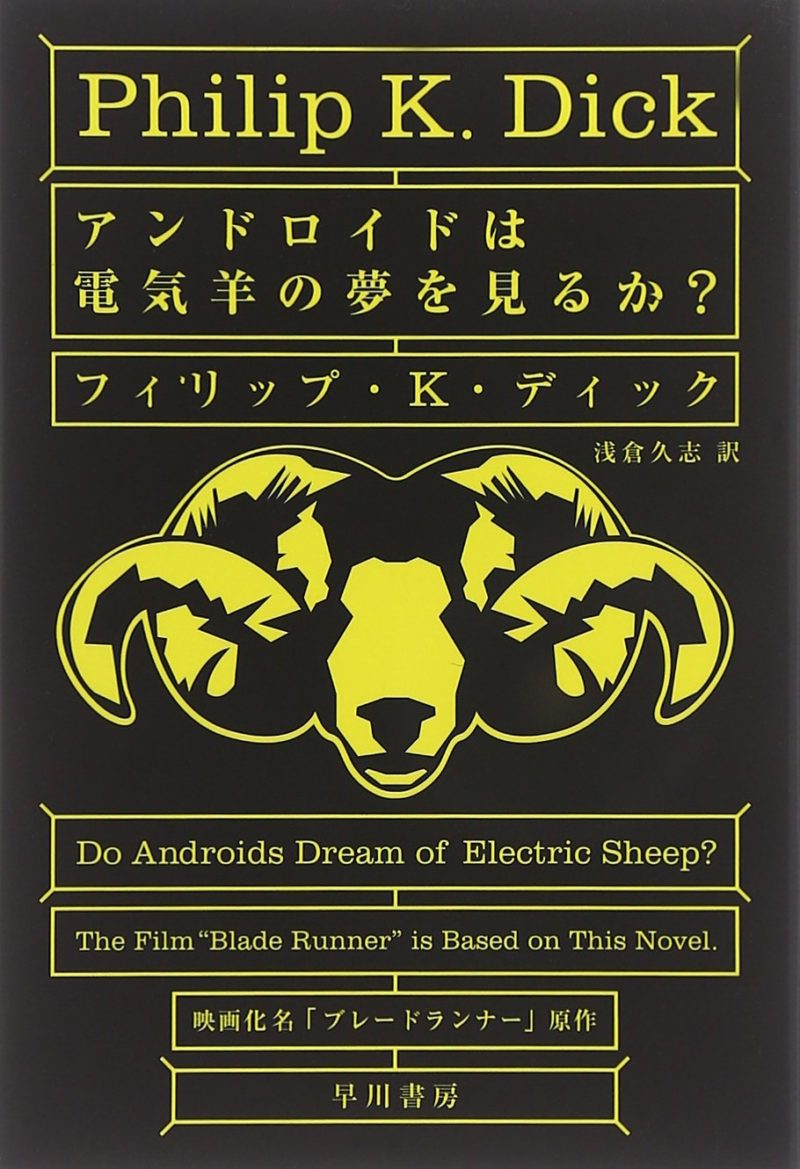

At a multistory rectangle of tinted glass in Daikanyama (Tri-Be-Ca-ish) I found a copy of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep as translated into Japanese by Haruki Murakami. The Tokyo Hayakawa publishing house has done a lovely design job on the book. There is an outer slip case which is gray and black and says “The Big Sleep, Raymond Chandler” in an Art Deco-like font of different point sizes. The “the” is white and the “Big Sleep” is black and there are some excellent looking Japanese characters in the upper right hand corner which are red. Remove that outer cover—which fits over the book with a near-frictionless precision, which actually reminds me of the way the subways glide into the stations—and the book itself is bound in pale green paper with a single pinstripe running along the upper quarter under a cursive  “h” (I assume for Hayakawa). I’d also found a copy of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes in Japanese, (trans. Ken Nobuhara) whose cover, in that same fitted slipcase, has eggshell blue letters on white, with little black silhouettes of multiple Holmeses smoking pipes; as well as a truly excellent Japanese Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (trans. Hishashi Asakura) with a bright yellow ram pictured under a charmingly direct note, in English, telling us that “The film Blade Runner is Based on This Novel.” When I brought the books up to the counter I was (per usual) showered with ‘hai’s (はい, yes) and ‘arigato’s (ありがとう thank you) after which came the beautiful formality of the transaction itself. A woman pulled a long strip of patterned paper from a wheel and, after some rapid, mesmerizing foldings, attached yet another layer of packaging to each of the books, which seemed to fit even more snugly and attractively than the slip cases. It’s a good thing I was able to enjoy all of this wrapping because I can’t read Japanese and so am reduced to a state of pure fetishism, seeing the books as nothing more or less than three dimensional rectangles of folded paper which when opened are full of vertical columns of figures that are, for me, totally opaque (though I have read and reread all the books in English). It occurs to me now that my provincial, consumerist, internalized japonaiserie was entirely behind the fugue state induced by the packaging. These were favorite books of mine going back to my early teens (even further in the case of the Holmes tales as they were read aloud to me by my paternal grandmother), and

“h” (I assume for Hayakawa). I’d also found a copy of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes in Japanese, (trans. Ken Nobuhara) whose cover, in that same fitted slipcase, has eggshell blue letters on white, with little black silhouettes of multiple Holmeses smoking pipes; as well as a truly excellent Japanese Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (trans. Hishashi Asakura) with a bright yellow ram pictured under a charmingly direct note, in English, telling us that “The film Blade Runner is Based on This Novel.” When I brought the books up to the counter I was (per usual) showered with ‘hai’s (はい, yes) and ‘arigato’s (ありがとう thank you) after which came the beautiful formality of the transaction itself. A woman pulled a long strip of patterned paper from a wheel and, after some rapid, mesmerizing foldings, attached yet another layer of packaging to each of the books, which seemed to fit even more snugly and attractively than the slip cases. It’s a good thing I was able to enjoy all of this wrapping because I can’t read Japanese and so am reduced to a state of pure fetishism, seeing the books as nothing more or less than three dimensional rectangles of folded paper which when opened are full of vertical columns of figures that are, for me, totally opaque (though I have read and reread all the books in English). It occurs to me now that my provincial, consumerist, internalized japonaiserie was entirely behind the fugue state induced by the packaging. These were favorite books of mine going back to my early teens (even further in the case of the Holmes tales as they were read aloud to me by my paternal grandmother), and  so it was as if I was recreating versions of my cozy habits, cast in an artificial shell of Japanese-ness. And it wasn’t just books that invited this sort of sensory covetousness but everything. Within two days of being in Tokyo I fell in love with an elevator, a light fixture, a handkerchief, many varieties of stationary, some doilies draped over the seats of a cab, a blue and white box of salt cookies with embossed plants on it. At one point I found myself, at the Tokyu Hands department store holding up a hubcap sized piece of black foam rubber saying “I must have this.”[1]

so it was as if I was recreating versions of my cozy habits, cast in an artificial shell of Japanese-ness. And it wasn’t just books that invited this sort of sensory covetousness but everything. Within two days of being in Tokyo I fell in love with an elevator, a light fixture, a handkerchief, many varieties of stationary, some doilies draped over the seats of a cab, a blue and white box of salt cookies with embossed plants on it. At one point I found myself, at the Tokyu Hands department store holding up a hubcap sized piece of black foam rubber saying “I must have this.”[1]

Some Thoughts About Garbage

The whole thing about Tokyo being super clean is especially interesting given that there are almost no public trash dispensers in the city. Really, I had to search sometimes for 10 or 15 minutes to find a place to deposit a napkin or an empty water bottle. Turns out this is not an accident. An established line of thinking about city planning asserts that if a trash dispenser is not ready to hand people tend to develop habits that lead to less littering.[2] Again a comparison with New York is irresistible: in Manhattan there are garbage cans everywhere and they are always overflowing. Overflowing so much that street corners often seem to be turning into cresting waves of debris. New York, in this way, is the inverse of Tokyo: there are more trash cans and more litter. But I was wondering: might we try this approach in NYC? What if we just took all the garbage cans away? Would the streets turn into mountains of trash? Or would the city magically cleanse itself?

Shinjuku

Japanese pop tends to be more aggressive, more mutant, more refulgent and cracked, than American pop. By “pop” I mean the broadest array of consumer branding, from youth fashion to movies and music and video games etc, and by “aggressive” I mean the point at which the original mass appeal starts to curdle into something menacing and abstract. The Shinjuku section of Tokyo is something like a laboratory for this curdling effect, and it’s about as close to the “Blade Runner” vibe as I’ve come across so far. It is a relentless and bewildering mash up of smells and sounds and panoramic assault of animated advertisements (one ad that has stayed in my mind: a chipmunk rotating inside a lightbulb), where grilled centipedes abut Florsheim shoes  on modular DIY shopping racks set up under huge, apparently improvised clusters of telephone lines and air ducts. One type of establishment that kept popping up in this neighborhood were the underground video game parlors. Far from the strip mall arcades I remember from my youth, these were more like Plato’s cave: addicts hunched in the dark in front of cinematic games with names like Wonderland Library and Soul Reverse. On a still lower level there were rows of people sitting and smoking (smoking is permitted) in front of a huge screen over which it said Star Horse 3 and which showed a Pixar-like horse race in progress, on which the seated spectators were placing bets. In some cases players were surrounded by fans and followers: tween girls in ripped jean skirts and heavy punk/Geisha make-up carrying huge embroidered pillows to their chests and guys in linen capes and untied basketball shoes many sizes too big and hair down to their asses. One of the game-players was wearing a white tee shirt that said WEIRD EMOTIONS on it in all black caps; another had on a jacket that said PATIENCE on the back.

on modular DIY shopping racks set up under huge, apparently improvised clusters of telephone lines and air ducts. One type of establishment that kept popping up in this neighborhood were the underground video game parlors. Far from the strip mall arcades I remember from my youth, these were more like Plato’s cave: addicts hunched in the dark in front of cinematic games with names like Wonderland Library and Soul Reverse. On a still lower level there were rows of people sitting and smoking (smoking is permitted) in front of a huge screen over which it said Star Horse 3 and which showed a Pixar-like horse race in progress, on which the seated spectators were placing bets. In some cases players were surrounded by fans and followers: tween girls in ripped jean skirts and heavy punk/Geisha make-up carrying huge embroidered pillows to their chests and guys in linen capes and untied basketball shoes many sizes too big and hair down to their asses. One of the game-players was wearing a white tee shirt that said WEIRD EMOTIONS on it in all black caps; another had on a jacket that said PATIENCE on the back.

The Scoreboard at Meiji Jingu Stadium

Anyone who has been to a major league baseball game in the last twenty years has surely noticed the way the action on the field is heavily augmented by imposing and sophisticated scoreboards. The scoreboards at places like Citi Field in Queens and Miller Park in Milwaukee and the Great American Ball Park in Cincinnati are towering multimillion dollar HD displays that seem at all times to be attempting to shoehorn the actuality of the game into the editable fluidity of television. The screens of course give inning by inning runs, hits and errors, and player stats, but they also show close plays in slow motion and from different camera angles (often eliciting cheers or boos), give instructions to the crowd (“Let’s Go Mets!,” “Charge!”, “Make Some Noise!”) provide trivia about baseball history or mark franchise milestones (“on this day in 1987 Paul Molitor went three for four extending his hitting streak to thirty-seven games”) and of course, bombard the spectator with advertisements. But here’s the thing: the scoreboard at the baseball game I went to in Tokyo had a whole different concept of what a scoreboard is meant to add to a live game. After a strike out at Meiji Jingu Stadium, where the Tokyo Yakult Swallows play, there’s an interstitial burst of what I will describe as operatic munchkin speed metal, which is incredibly loud and functions the way a sitcom cue does at the end of a scene (think here of the slap bass riffs in a Seinfeld episode). Then when the inning changes over the scoreboard plays bonkers techno pop—like Katy Perry fused with Couperin harpsichord music but with the whole arrangement jacked up with Slayer-style double kick drum. The seventh inning stretch involved a choreographed group singalong in which everyone pulled out tiny umbrellas with Swallows logos on them and sang in unison to a Kurt Weill-ish ballad that was apparently about a hoped for Swallows victory (it worked, they won). Added to this are all sorts of little quirks of translation that, for an American brought up on the often quite intricate and fine-grained language for the discussion and analysis of baseball, was appealingly odd. For some reason whenever there’s a walk it says CHANCE on the scoreboard; the order of ball-strike counts is inverted, so a full count is a 2 and 3, not 3 and 2; at another point, the scoreboard was used to stage a split-screen Rock/Paper/Scissors game between two fans, apparently chosen at random.[3] And yes, there are lots of ads, many for beer, which makes sense since at all times during the game there is a formidable squadron of “beer girls” roaming the stands in backpacks equipped with little kegs and a spout attached to a hose, filling and refilling plastic cups with the Swallows logo on it, and which were, I noticed, entirely picked up and disposed of by the time we left the stadium.

Relaxing at the Sakura Tower Hotel

In the basement of our hotel, next to the fitness center and the spa, was a glassed in room with the words Relax Lounge set in the glass in some kind of bronze wire. The room was nearly bare except for a double set of “Relax Chairs.” These were something high end Lay-Z-Boy recliners crossed with the torture table in Kafka’s “In The Penal Colony”: luxury leather chairs equipped with all sorts of moving ligaments and panels that push you and squeeze you and smash you in different spots and basically give you a hardcore industrial massage. One of the massage effects feels like fifteen billiard balls hooked together in a quilt electrically powered by pressure valves which move up and down your back and ass and thighs slowly as the spheres shake and vibrate. I must confess I was never able to “relax” in these chairs because I kept thinking about what would happen were it to malfunction, as in the Kafka story when broken cogwheels start flying out from the top of the machine. There were no attendants nearby, all the controls were in Japanese and I assumed that at least sometimes these chairs had glitches. But it was fine, and my son loved it and it became something of a ritual to visit the Relax Chairs after a day exploring Tokyo. Further, we agreed that the control panels attached to the arm rest of the chairs looked cool as hell.

Inari, Kitsune

From Tokyo we took the high speed Shinkansen line, or “Bullet Train,” south to Kyoto—the Imperial capital of Japan before it shifted to Tokyo (Edo) in the middle of the 19th century. Announcements on the bullet train are in Japanese, and then everything gets repeated in a silken hyperefined quasi-British English, like a female A.I. version of J.M. Coetzee, and then attendants in prim, spotless uniforms move through the car and give you these marvelous little hand wipes in sealed pink packets. The first thing we do when we get to Kyoto is make a trip out to the astonishing FUSHIMI-INARI shrine. The shrine is a series of thousands of vermillion orange gates of lacquered wood (Torii) built up the side of the mountain. As we climbed the steep stairway that run under the gates (it’s quite a workout) signs began to appear warning us not to befriend the wild boars that live in the surrounding bamboo forest. Between the columns spiders had constructed five foot wide webs, and crows zinging around above the bamboo actually said “caw.” There were strange smells, like spent firecrackers mixed with sesame. The tops of shrines peeking up from behind the orange gates are adorned with the iconic fox (kitsune 狐 キツネ), a supernatural creature linked to “Inari,” the Shinto god of rice. You see these foxes everywhere along the path, many of them holding keys in their mouth. I asked about the keys and was told (again, with overwhelming courtesy) that they represented the keys to the rice granary, and so the offering of Sake, traditional Japanese rice wine, is a way of getting into contact with Inari. We reached the main shrine at the top of the mountain, having passed under thousands of the orange gates and without having encountered any boars. There was old Kyoto, spread out silently under us. It seemed crazy to me that it had been here—that all of Japan had been here—the whole time.

Footnotes

- [1] See William Gibson’s “Shiny Balls of Mud” where he describes his own visit to this store. The essay is included in his book Distrust That Particular Flavor. ↩

- [2] I am indebted to Adi Shamir-Baron, Commissioner of Landmarks Preservation under New York Mayor Bill De Blasio, for explaining to me how many cities have experimented with this approach to eliminating litter. For efforts in San Francisco, see, https://www.citylab.com/life/2015/11/fewer-trash-cans-less-trash ↩

- [3] A Japanophile friend later pointed out that this meant there was a “chance” now for a run because someone was on base, though I found it odd then that when there was a base hit it did not say “chance.” ↩