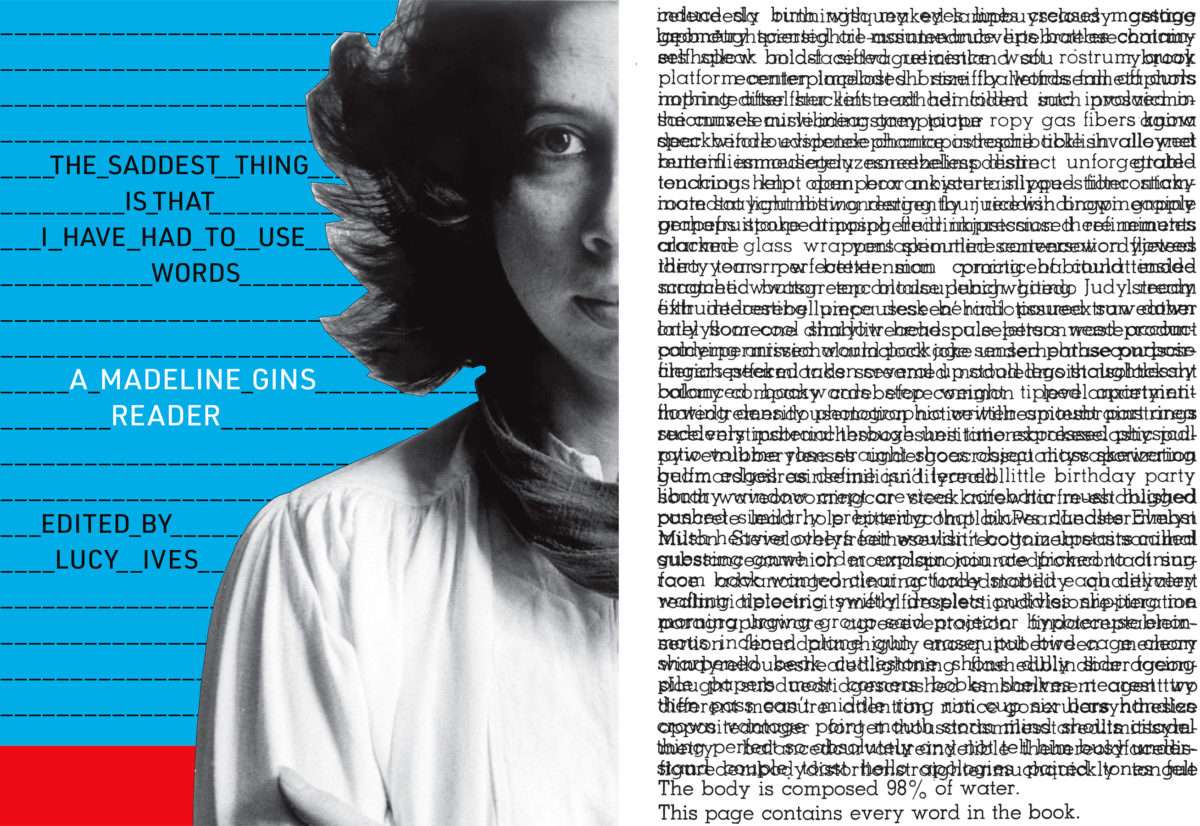

Several months ago I received a review copy of The Saddest Thing Is That I Have Had to Use Words: A Madeline Gins Reader, an extensive archive of the artist and writer’s published and unpublished poems, prose, and experimentations, edited by the poet Lucy Ives and published by Siglio Press. Lucy and I agreed to a podcast interview recorded at a scaled model of Gins’ Reversible Destiny “procedural architecture” anti-aging installation—the Biotopological Scale-Juggling Escalator at the Dover Street Market in New York City. Then New York City went into lockdown. So we adjusted our plans. To pay homage to Gins, an artist, philosopher, and writer of the L A N G U A G E poem and avant-garde ilk (though I'm sure she'd eschew the distinctions), we turned the interview into a game.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in