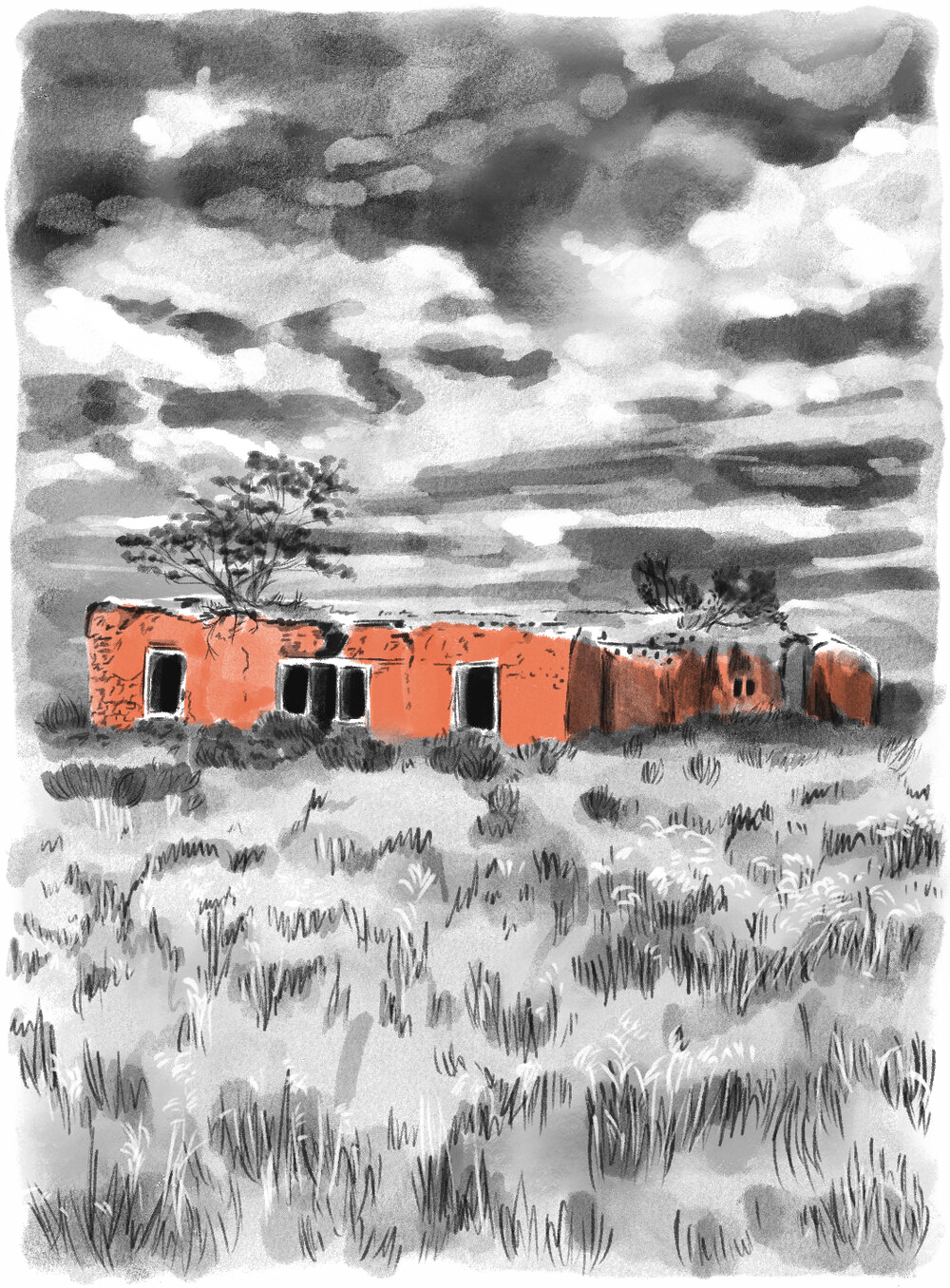

They say that before you buy a house in Santa Fe, you should visit it at three different times of day. That way, you can see how the quality of light changes the color of the stucco.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in