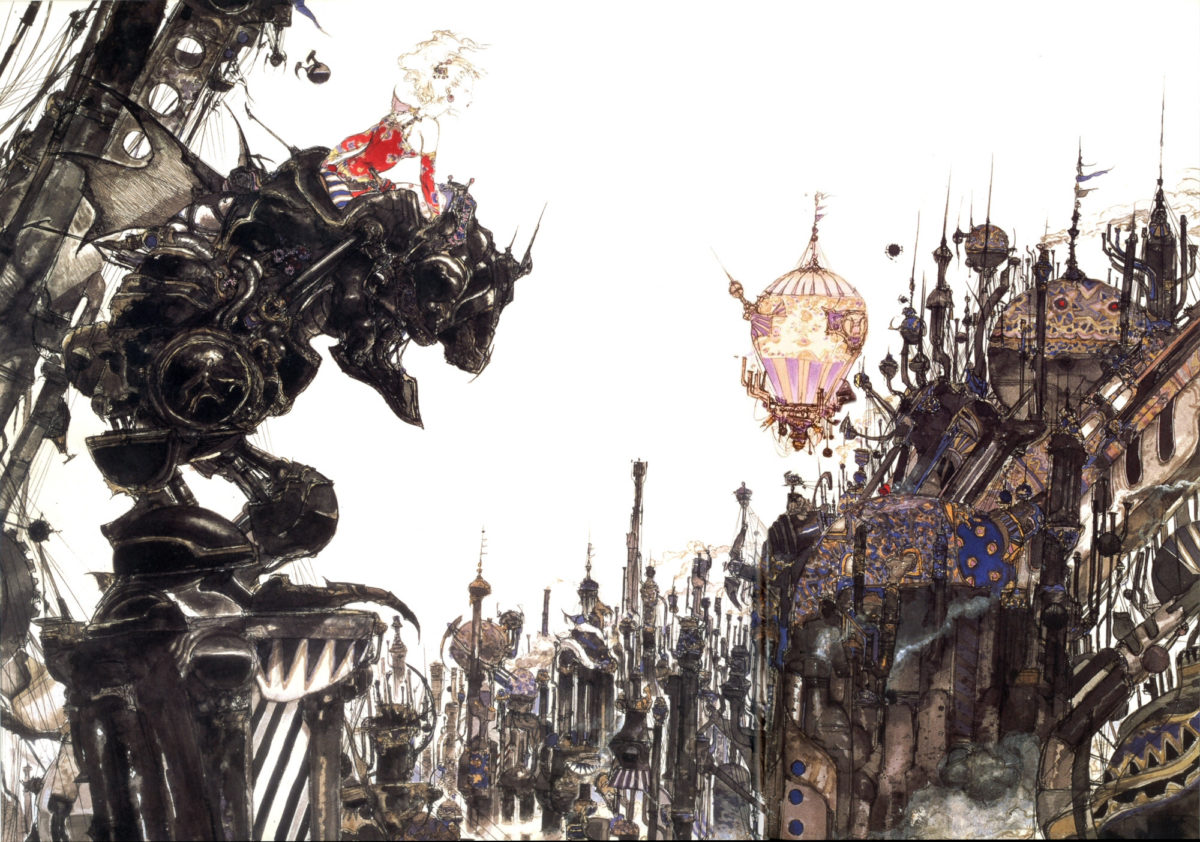

Below is an excerpt from Sebastian Deken’s book on the classic Super Nintendo role-playing game, Final Fantasy VI. This chapter of the book—which for the purposes of publication on The Logger has been split into two parts—is an in-depth analysis of the game’s legendary and evocative soundtrack from longtime series composer, Nobuo Uematsu. Final Fantasy VI has received numerous ports since it first released in 1994, and is widely considered to be among the greatest video games ever made.

The pipe organ is a lumbering, complicated machine of an instrument. It requires your entire body to play and hulks out music through dusty, antique science. Hundreds, thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of delicately assembled mechanical parts bellow a supply of wind through ranks of different-sized pipes. The pipes can produce sounds ranging from monstrously deep to twinkly high, in sometimes hundreds of timbres. Organs can be small and light enough to carry or weigh hundreds of tons and fill up a freight train, but a pipe organ is more than the sum of its many, many parts: It creates a whole world of sound and gives you no choice but to live in it. Like the cathedrals they often inhabit, pipe organs exist in outsize proportion, engineered by humans to evoke the presence of the beyond. Screeching treble and thundering bass conjure the Alpha and Omega; the sound can come from all directions at once, becoming an invisible force that barrels through the bodies of its listeners. Organists sit behind their consoles pressing keys, pulling stops, flipping levers, and stomping on pedals, operating a mech suit that blasts out magic. Music, that most human of endeavors, becomes extrahuman.

At their cores, pipe organs are binary instruments: Their stops are on or off, their sound crescendos and decrescendos accordingly, and they render our input into a primitive kind of digital output. Organs are a triumph of engineering, but they are also an artifact. They have been outmoded in many ways by newer keyboard instruments such as the piano—which, though a complicated machine in itself, responds more organically to the player’s input. Pianos have, in turn, been outdone by advanced synthesizers, which not only replicate piano sounds and maintain pressure sensitivity but can also mimic hundreds of other instruments—including the pipe organ. Like humans against Espers, the analog and digital have been warring with each other for generations. And, like the Espers, the analog—for now at least—seems to be creeping toward extinction.

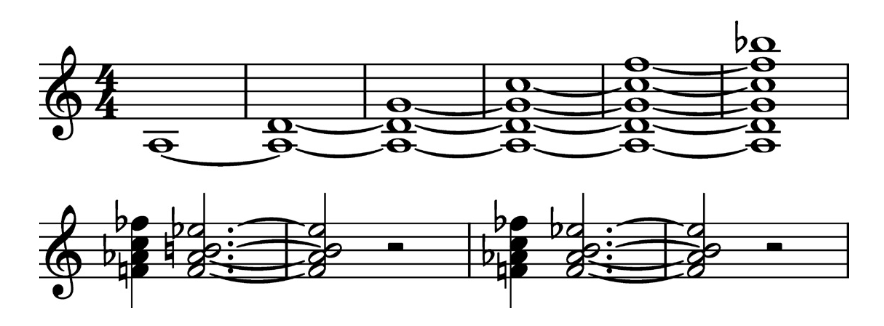

A pipe organ is the first sound you hear after you flip on the SNES to play Final Fantasy VI. The game’s opening music is a series of six—yes, VI—pitches stacking on top of each other in slow succession, each one a perfect fourth away from the one preceding it (figure 3.1). The perfect fourth is not particularly special in itself—it’s just a musical interval, the distance from C to F on a piano. But when you stack fourths on top of one another with nothing to undergird them, they start to get unstable. If one were to keep stacking and stacking, you’d hit all twelve notes in the chromatic scale before you circled back around to the first note in the sequence. Think of a Jenga tower: It’s sturdy for a few levels, but the taller the tower gets, the less stable it becomes, and the more you expect it to crash down.

FF6 is a tower that crashes down. First it crashes musically, within the first few measures of the introduction. Then it crashes metaphorically and literally, in that Kefka’s hubris and the instability he visits upon the planet—represented by the tower-lair he constructs for himself in the World of Ruin—crashes down to the ground. The collapse of the organ music, after those first six notes, is rendered in two ponderous, dissonant chords. On screen, lightning flashes in a charcoal-grey sky, and “FINAL FANTASY III” appears in flaming letters.

The beginning of the game, the stacking pitches on the organ, gestures toward the end. The game’s final battle, where this very music repeats itself, gestures toward the beginning. Humanity repeated its mistake with the War of the Magi, and the music repeats, too. Maybe in another thousand years, humanity will dust the organ off for a threepeat.

Uematsu’s instrumentation throughout the game reflects a contrast of acoustic and digital, balance and ruin. His use of pipe organs, electric instruments, and synthesizers closely correlates with the unnatural use of magic, evil, and the apocalypse. Electronic instruments feature in every piece of battle music; from the oft-heard “Battle Theme,” in which a distorted electric guitar riffs in the background; to “The Decisive Battle,” in which a Hammond organ leads with the melody; to “The Fierce Battle,” in which the primary melody is played on a synthesizer; to “Dancing Mad,” the final battle music, which features both a pipe and Hammond organ.

Synthesized instruments also figure in heavily when a confrontation with Kefka is imminent: in in the Magitek Factory (“Devil’s Lab”), before Kefka tries to convince the heroes that Celes has been working as a double agent; on the Floating Continent (“New Continent”), before Kefka seizes control of the ancient statues and sets off the apocalypse; and in Kefka’s Tower (“Last Dungeon”), the final area the player explores. With the exception of Uematsu’s signature omnipresent electric bass, organs and electronic instruments appear rarely in other places, and are never associated with the heroes directly. (For the purposes of this discussion, let’s count “Techno de Chocobo” as a running series gag and not as a reflection of Chocobos as ostriches of the damned.)

This kind of thoughtfulness is laced throughout FF6, in the painting of portraits, landscapes, events, and ideas—nouns, basically. It’s not just the presence or absence of organs and synthesizers; it’s the other astute choices in instrumentation, the way his melodies and harmonies reflect their subjects. Whether we as listeners actively pick up on these choices or not, they impact the way we interpret the story, take in the sights, and relate to the principal characters, each of whom has their own fully realized theme song—the most important device in the game’s soundtrack, one that pole-vaults us across that Mario Pit.

Cyan

Doma, an insular kingdom in the East, is battle-scarred and under siege. When the player arrives on scene, Imperial troops are beginning their final surge toward the castle gate—they’re just a step away from taking the kingdom once and for all. A sentry reports to his superior inside the keep: The latest wave will be too much for them to hold back. Doma will fall. From offscreen, a shout: “A moment, Sir!”

A man strides onscreen: heavy-lidded eyes, black hair pulled back in a ponytail, bare arms, armor and boots in deep blue. It is Cyan, the knight/retainer to the king, an unparalleled swordsman. He steps between the two soldiers and, as though asking them to dance, says, “Allow me the honor!” Then he bursts through the gate and singlehandedly dispatches the entire Imperial contingent.

Cyan and his compatriots are coded as “other.” The kingdom’s sentries and troops wear powder blue turbans and boots and pale green robes that hit above the knee. Cyan’s sprite has eyes a pixel narrower than the other characters, and he is the only character in the game with black hair. His speech is formal and archaic, leaning heavily on “thou,” and he and his fellow Domans show unmatched deference to their king.

Cyan’s theme is led by the shakuhachi, an end-blown bamboo flute closely associated with spiritual practice during Japan’s feudal history. Beyond the shakuhachi, the piece is undergirded by a booming, low timpani, likely meant to represent taiko drums, and a regular jingle of handheld suzu bells, a sleigh bells–like instrument used during Shinto ceremony. This music—peppered with instruments not typically found in Western orchestras—marks Cyan and his kingdom as “others” as much as his appearance does. To clarify, this interpretation comes from an American gaze: A Japanese audience may read Cyan and hear his music in a very different way.

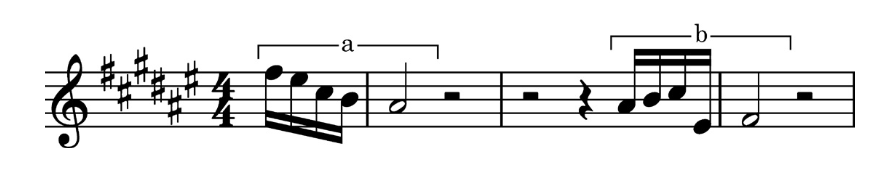

In the first half of the theme, the melody alternates between sustained notes and quick movements (figure 3.2), swishing and steadying with a fencer’s precision—a kind of musical iaido demonstration. The harmony does not change, middle-register strings pulse steadily, and low strings and percussion sound in a distinct, repetitive rhythm—all implying constancy, even conservatism. This bears out in the script: His archaic speech, his discomfort with machinery and technology, and his buttoned-up sexuality heighten this conservatism to comic proportions. But he is also the sole keeper of his people’s memory and traditions, and the steadiness of these opening measures, coupled with the unique instrumentation, speak to this sacred burden.

Doma Castle’s water source is an architectural feature. It’s built over and into a river. After Cyan’s victory over the Imperial contingent, the nearby Imperial camp goes abuzz with activity and Doma’s waters turn an angry fuchsia. Almost immediately, the citizens begin to double over in agony, then collapse, some of them tumbling over the parapets to the stone pavement stories below. It’s a chilling sight. By this point in the game, the gap between the player and the game world has closed far enough that these 16-bit sprites are real as humans. This is genocide, and the player is helpless to stop it.

Cyan runs to the king, whose vision has left him, and whose every breath is like fire in his lungs. He dies with Cyan at his side. Cyan and a single surviving sentry split up to look for survivors, but the sentry is never seen again. Doma is extinct.

The music’s chilly formality only lasts through its first section. It doesn’t melt away; it sublimates. There is a short bridge during which the pace doubles—in the pulsing strings, in the rhythm of the shakuhachi—with a feeling of impatience or building pressure. In the third and final section, the shakuhachi and the steadiness disappear entirely. The contrast is unexpected and magical.

What the player hears is a romantic reinvention of the first section’s melody, played over fluttering woodwinds—this is the part that recalls Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet. Cyan has suffered tremendous personal loss already, and it doesn’t end with his people and his king. During his search for survivors, he finds his wife dead, and pulls his son’s body hopelessly out of bed. The romanticism of the theme’s final section reflects abiding love—for Doma and for his family—but it’s tinged with unspeakable grief. As the romantic cycles endlessly toward the traditional and back, the music suggests a polite but futile instinct to avoid overt displays of emotion. When he discovers the remains of his family, he can only utter, “Dear me…”

Cyan is a deeply layered character, but his depth may not come through in the first half of the script: His archaisms, his discomfort around women, and his ineptitude with machinery are used most often as punchlines. Thinking about the pain he carries with him breaks my heart, yet it plays only a small part in the main plot. The optional storylines in the second half of the game are where we see his whole self: a man who crafts silk flowers and writes poetry for a bereaved woman, who reads up on machinery, who keeps a hidden stash of racy photos. You explore his subconscious and plumb into his grief by literally entering his dreams. All of this character development is optional—unless you find him on his secluded mountaintop and take him back to his ruined kingdom, you won’t capture it all.

His theme music, then, is the principal way you learn who he is. His melody spans just over an octave and a half—a respectable range for an opera aria. This breadth reflects, in a delicate, subliminal way, his range of roles on screen: father, husband, widower, comic relief, savior, and protector. To my ear, it contains the starkest contrast of any of the characters’ musical portraits. Every other theme, as it moves from section to section, maintains a clear personality: The gambler Setzer’s stays heart-pounding, the secretive Strago’s stays suspicious. Even Terra’s theme, moving from cool to warm as Terra morphs between human and Esper, retains its march-like quality. Cyan’s, though, drops its sword and kneels.

Relm

Relm is a remarkable ten-year-old: a supremely gifted painter and, though human, an heir of generations of magical abilities. Her grandfather, Strago, is a grizzled monster hunter and zoömancer—but Relm’s work isn’t with animals. Her magic is art. She renders her subjects so vividly that, when she sketches monsters on the battlefield, her work comes to life and fights back against its subject. This is a fitting power for a character who stirs up so much trouble: She sneaks out of the house, pulls pranks, throws precocious barbs at the other characters—and one time she paints a portrait of a sexy goddess, and her painting becomes possessed by a demon, and the painting nearly kills everyone. Usual kid stuff.

When she’s introduced to the player, she runs down the stairs of her grandfather’s house, interrupts his conversation with the other characters, and accidentally spills the beans about her family’s magic abilities—kept secret from the rest of the world. The player hears immediately that there’s more to her than impetuousness. Her music is darling and downcast, and her title card reads, “In her pictures she captures everything: forests, water, light… the very essence of life.”

It’s all so incongruous with the cheeky child the player meets. Based on the script and direction, we might expect a saucy, upbeat number. Instead, we get loveliness. We might expect her title card to describe an energetic, impulsive kid. Instead, it reads like a translation of Wang Wei’s tranquil poem “Deer Park.” Relm reads that way, too, once you get to know her; her impudence veils simple, abiding love for her grandfather. In the World of Ruin, she betrays her secret affection for Strago when she wiles him into fulfilling his lifelong goal of defeating Hidon, the unbeatable monster. In the final battle with Kefka, she proudly admits that she fights for her brave grandpa. And, in the post-credits sequence, she expresses a sincere wish to preserve him in portrait—one that probably won’t murder him.

There are deeper elements shaping Relm’s character. Her mother died when she was quite young, leaving behind a memento ring. This may be the only souvenir Relm still has of her mother. Her father abandoned her not much later. That pain is still fresh—she relives it in her onscreen nightmares: She curls up on the floor, crying for her father to come back; her dog barks at her, then dashes out the door to chase after him; Strago looks down at her silently. It’s possible that—in her first moments onscreen, bounding down the stairs—she’s hoping against hope that her dad will be there. (He is— but unrecognizably, in the guise of the ninja Shadow.)

It’s easy to overlook Relm as you play through the game. At first blush, she seems to be a stock sassy tween, still watermarked by Shutterstock. Compare this to Cyan’s time on screen, when the player gets to know him a bit, even without the optional World-of-Ruin follow-up. Learning the entirety of Relm’s story is completely optional, and it’s impossible to do so in one playthrough. Just as the Floating Continent falls, the player has to make a nail-biting decision that determines whether Shadow lives or plummets to his doom. If the player chooses to save him, they will never get to see Relm’s recurring nightmare; if the player chooses to leave him, they never get to see her father’s.

Because Relm joins the party last—and because her in-battle talent is fun in theory, but not all that useful in practice—it’s easy to brush past her without much thought.

Her theme song, however, softly asks you to take a second look. Its first twelve measures are harmonically static—starting, and sticking to, F-sharp major. A flute, oboe, and bagpipe play a series of gentle, descending fragments spaced widely apart. The effect is sweet, but immature—not quite cohering the way an adult might hope it would. There’s room for imagination—or frustration—between each fragment. You might find yourself asking: Where is this going?

The melody’s somewhat baffling loveliness may distract you from its predominantly downward motion. Its eyes are cast on the floor, not out of shyness—Relm is absolutely not shy—but out of sadness. That descending fragment is repeated insistently and irregularly, alternating with a pattern that turns over on itself (figure 3.3). The pattern’s repetition suggests she revisits, relives, and rethinks this sadness often. It has always interested me that the theme contains broad measure-and-a-half spans without any melodic motion—“Deer Park” stillness. Maybe this stillness is time stretching out in front of her, as it does when you’re a child; maybe it’s daylight; or maybe she’s stepping back from her canvas, thumb to her chin.

In the final eight measures, a duet between oboe and bassoon finally introduces some cohesion but, as this happens, the piece changes key into a melancholy D-sharp minor. Still sweet, but darker and tenderer—a bruised pear in a still-life. Relm has suffered too much for a ten-year-old, and this is where we really start to feel it. The melody cuts unexpectedly deep, and the harmonies begin to flow in a way they didn’t before. The surprise of this turn is what makes it heartbreaking—the tears came from nowhere. But they don’t linger: The melody rises with hope, a measure of eighth notes tilts back and forth—a shrug of the shoulders, a playful twirl, or a steadying on a balance beam—and two half notes sigh, comforted, before the piece loops back to the beginning.

Relm’s melody, fragmented as it is, spans just under an octave and a half—similar in range to Cyan’s. This subtlety reflects a depth of character too easily over-looked. Her music aptly mixes grace with doubt, pain with promise. Light and dark, grey and color.

Uematsu has said that Relm is his favorite character, and it makes sense for him to have an affinity for the young artist. He has Relm’s magic in him somewhere, in his gift of giving life through his work. He picks the right colors, makes the lines sharp and clean, and gets the framing just so. Through this instinct, he renders characters with remarkable, moving efficiency. Relm’s theme is just twenty measures long, but it tells us a complicated story. It’s childlike without being childish. It’s a deft illustration: a precocious painter, a soft heart, a skinned knee.

Sebastian Deken’s book on Final Fantasy VI is available for purchase via Boss Fight Books. Stay tuned for the second part of the piece next week.