In Taoism, the wisest of humans can become immortal. Through spiritual work and alchemy, a dedicated sage can discover the philosopher’s stone, transcend the physical form, and dance through the celestial bodies forever.

On earth, we can only aim for longevity. We approach immortality by adding up years. In the mountains of the island of Sardinia, there is a region filled with centenarians—century-old people who live full healthy lives until their death. They eat well and maintain vibrant communities for their entire lives. The aged are celebrated. This place is one of many so-called “blue zones” where people get the highest quality and quantity out of their timeline. For the most part, these places are on islands, comfortably isolated from the stimulations of the contemporary world.

Unlike immortality, longevity is conceptually bound to horizontal time: a life is a train ride to be taken as far as possible. Time ticks forward at the same objective, mechanical rate. But true immortality would change the nature of how we regard time. Immortality is infinite. Time loosens its meaning. All of history is experienced as one unpunctuated, timeless moment.

Consider time as a vertical phenomenon, with each moment plunging infinitely inward. We can, perhaps, stretch a human lifetime from 100 to 1,000 years, and we can also stretch the feeling of a single second. Like matter, time can never be magnified away, only perceived in smaller and smaller increments. This kind of time is relational and subjective. Each of us only knows our own internal sense of time.

This notion of time may originate from Eastern spiritual tradition, but we all experience this ebb and flow. Time is relative and every day is experienced at a different rate. Parents watching their children grow say, “You are growing up too fast! How can I slow it down?” This is another way of saying, “How can I alter the way time feels to me?” Or people say, “Time flies when you’re having fun,” because they understand that pleasure eats time. When life is easy, no one counts seconds.

Discomfort, on the other hand, draws out time, extending each second into eternity. A bad day feels like it will never end. In this way, the wrong quantity (too much or too little) of stimulation (i.e., pain) can slow time. A similar effect can also be achieved by adjusting the quality of the stimulation.

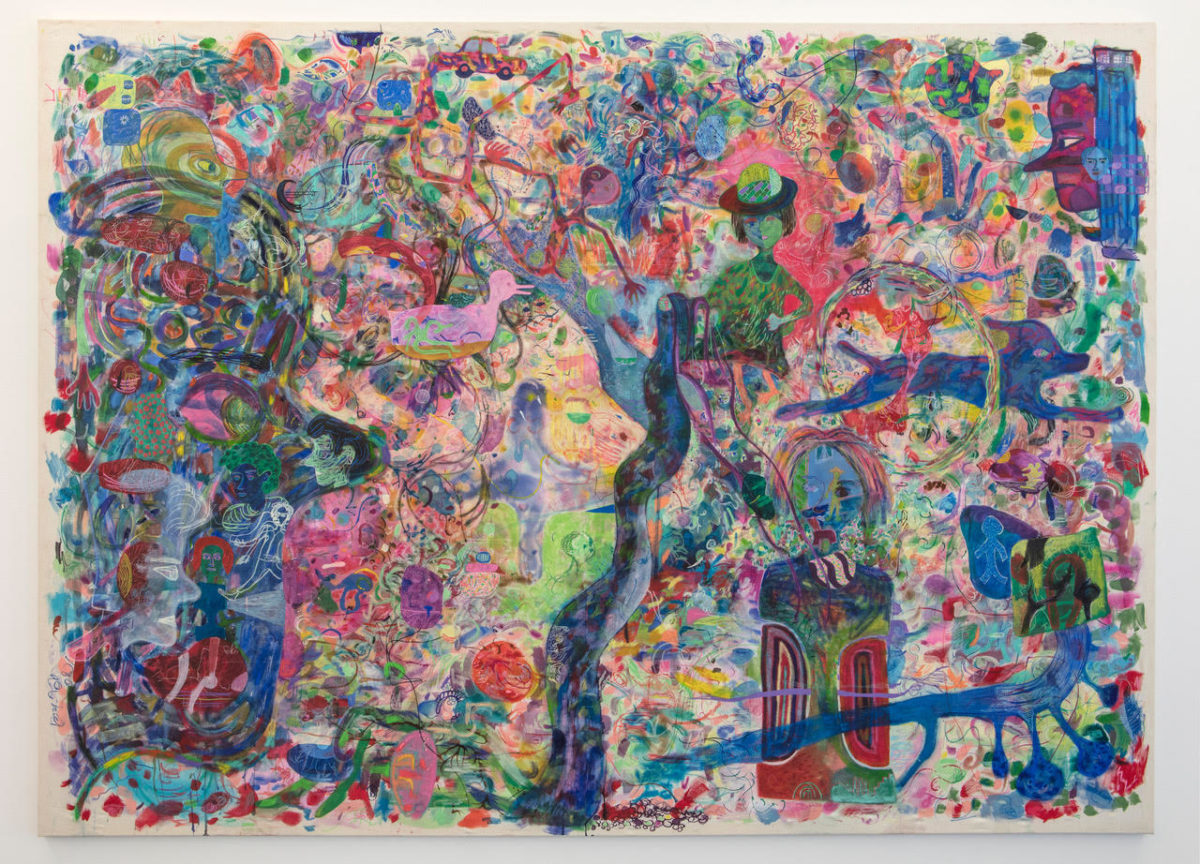

Untitled, 2021

Pastel, watercolor, ink, acrylic paint and marker on canvas

180 x 250 cm

I have always felt the expansion of time through newness. Novel stimulation has been my most effective portal into the feeling of immortality. Do something new and time seems to expand in every moment. The first iteration of an activity is vivid; every millisecond seems to light up the mind. But repeat the same action and each iteration increasingly fades away. By the umpteenth repetition of any task I can’t seem to hold on to the experience. When time all contains the same information, who can distinguish one moment from another?

I’m thinking of a weekend trip I took a decade ago to the river. I can sharply recall the place, people, feelings, and individual moments. For me, the memories of that time are yoked to that location, which makes for easy access. The stimulations of a new environment codified my perceptions. Memory and space are tied together, which is likely why people throughout history have constructed “memory palaces” in their minds to store impossibly vast archives of information.

The experience, for me, has been a lesson in retaining memories. In movement, I could become creative with time, treating duration, or psychological time, as a material to be sculpted in space. With each distinct location, I amassed a thick mental folder of impressions, but the longer we stayed there, I began to notice an inherent limit to how many impressions I could hold from a single place. When the feeling of stagnation arose, we moved on. In comparison, thinking about the previous six years, spent in a single apartment, seems like a haze.

Maybe the human mind is designed for experiencing time through nomadic living. Maybe the mind falters with too much repetition in a single location. Humans lived for 200,000 years in a nomadic or semi-nomadic state, moving seasonally, as needed. But we’ve only lived 6,000 years as domestic, location-bound people, growing our food rather than finding it, staying put in permanent dwellings.

But living on the move felt natural to me. At times, I imagined a post-Airbnb future in which homes are exchanged freely—a contemporary revival of the nomadic life way, in which everyone is fluid with their location.

But as of now, we live in a time when domesticity is the norm, and daisy chaining your living situation is considered dubious and unstable. When I have told people how I lived for this itinerant period, most of them squinted and scratched their heads; but every so often I noticed someone’s eyes light up, as if they recognized the deep urge within them for perpetual relocation. I understand why people aren’t eager to live like this. Civilization is not intended to be used this way and it can make for inconveniences that chafe over time.

So my wife and I have decided to end the nomadic life and enter a more stationary one. We will continue to travel, but will now have a steady home, a place to receive mail, accumulate objects, and enjoy the pleasures of ownership. Our future location will be reliably known for at least a few years to come. Time will begin to drift by and I will find other methods to expand duration.

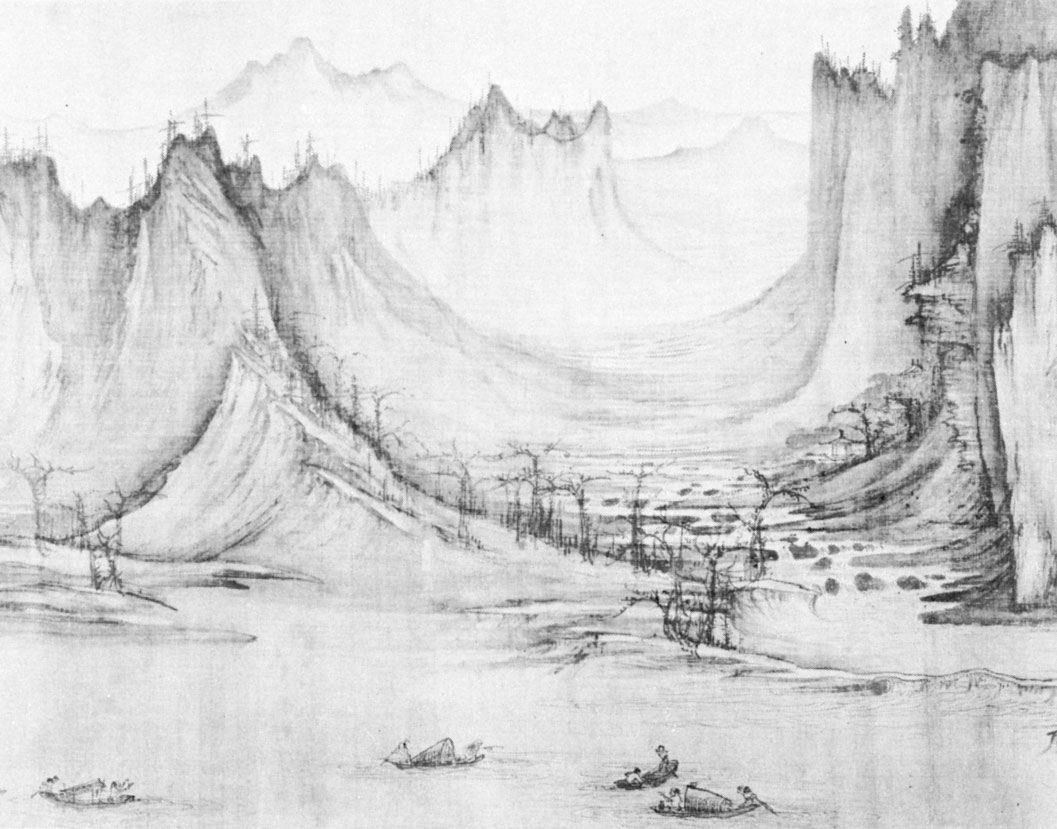

I take a little pleasure in knowing that the Taoist immortals lived like this, too. In their earthly existence, before enlightenment, they inhabited caves on mountaintops, far away from cities, and used stillness as their way of bending time. Over decades, they meditated without a glimmer of stimulation to distract them. Occasionally, local townspeople would climb the rocky hillside and bring these hermits food and clothing, because they understood the important, essential work happening in these caves. While the valley dwellers spent their days immersed in the flow of civil time, above them, the door to immortality was being held open for anyone who needed to pass through.

This essay was published on the occasion of Max Brand’s exhibition, Creative Mood, at Galeria Marta Cervera in Madrid, Spain.