This is the fifth entry in a series in which writers give a report on the weather. Any meteorological statements made may range from the personal to the scientific, from observable weather to the felt. Read the first entry, by Andrew Durbin; the second entry, by Amina Cain; the third entry, by Madeleine Watts; the fourth, by Andrew Durbin.

I’ve only recently moved back to Australia, to a Melbourne bayside suburb that is wealthy and capital-L Liberal (to say you are Liberal in Australia means you support the major conservative party). I am neither capital-L Liberal nor wealthy. When running along the Elwood foreshore, the fragments of conversation I pick up all seem to be about money, bollarded by platitudes:

If I could just save five K, put it into shares.

Don’t know why she stuck with him for so long. He didn’t have any money, anyway.

But at the end of the day…

Well, it’s all water under the bridge.

The last time I lived in this city, I was married. I lived—we lived—in a book-lined Edwardian in the quaint, quasi-industrial inner west, with cat and clawfoot tub and respectable sound system. There were fireplaces in every room, stained-glass windows, a garden at constant war with us. Packing tape for insulation, subscriptions to everything, no gray in my hair.

Was I happier then? Inconclusive. I listened to about the same amount of Jason Molina then as now.

Was I more hopeful?

A lot can happen in five years. The global average temperature can increase to 1.04 degrees above the pre-industrial baseline. Glaciers can recede at rates that warrant revisions of the word “glacial”. Oceans can measurably warm and rise and acidify. The Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest living organism, can bleach by half, become a signifier, a man-made catastrophe by which to measure other man-made catastrophes. Pacific gyres of particulate plastics can grow to demand new landmasses for comparison—though Bigger than Bolivia, for whatever reason, does not carry the same heft as Three Times the Size of Texas. The single-figure population of northern white rhinos—emblematic of extinction for how many years?—can be depleted to a single sex. Meanwhile, thousands of less storied species can blink from existence without our collective notice or concern.

Change of many kinds is occurring at an accelerated pace, outstripping even the more sombre forecasts, and so a year—or five years—seems densely packed, longer in terms of quantitive events. At the same time, there is a sense of grandscale groundrush, a plummet towards collapse too fast and terrible to comprehend.

For as long as memory allows, the closing down of a day, the elapsing light has brought on a turgid sense of dread, panic, guilt, melancholia—most starkly one of loss, or the threat of losing. A Rilkean keel, hardwired into each day, that things are unrecoverable, irreparable, that it is too late.

(Recently it was suggested that this was an association formed in my childhood, having to return at dusk to a home that was not home. Maybe so. But whatever the origins, it has been amplified to greater significance in adulthood.)

How to talk about the current Australian climate—how even to observe, or litanize, within the limited scope of one’s short lifetime—without fear of doom-mongering? Does it do any good to remind ourselves: these will (very soon) be the good old days?

On blood-warm evenings when the air is sultry with salt and magnolia and two kinds of jasmine, people gather along the shoreline; sprawls of families and friends backlit by the just-slipped sun, children wading out into an ocean as flat and lustrous as liquid mercury. All of this like a memory of lost footage, the scene of some Rapture or other.

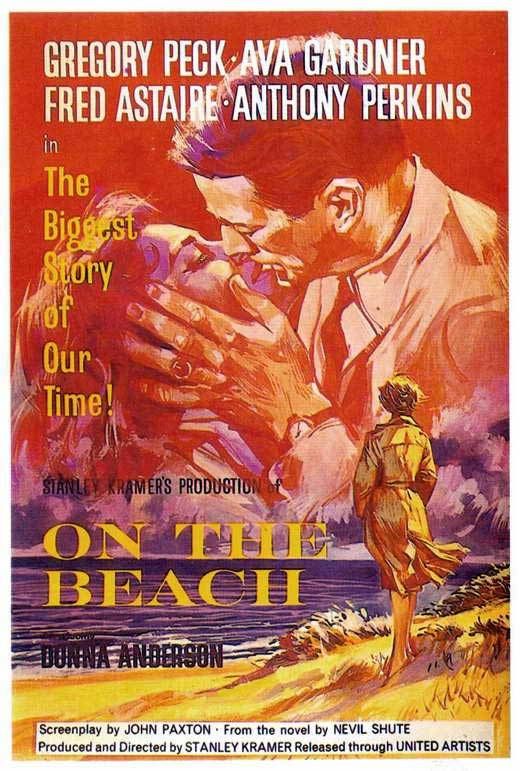

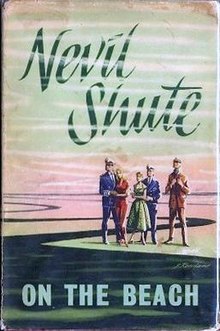

Since moving back here, I’ve been thinking about On the Beach, Nevil Shute’s 1957 novel about nuclear apocalypse, adapted to screen two years later by Stanley Kramer, and filmed just a little way along the coast.

Two days after Christmas I pick up a battered first edition hardback—best wishes for 1957 inscribed on the flyleaf—from an enduring secondhand bookstore whose inert, monumental cats are often mistaken for shop fittings. Opening the novel later in the afternoon, I’m slapped by that day’s date in the introductory paragraphs—

Christmas was over, and this—his mind turned over slowly—this must be Thursday the 27th. As he lay in bed the sunburn on his back was still a little sore…

—thus eerily amplifying the pervasive sense of eschaton.

The novel begins from the perspective of Peter Holmes, an Australian Lieutenant Commander (the rank Shute himself held by the end of WWII). Nuclear holocaust has wiped out much of the northern hemisphere, and fallout is steadily drifting towards Australia from the “hot zones”; the theatres of the “short, bewildering war … of which no history had been written or ever would be written now.”

Global air currents are steadily distributing particulate matter, radioactive dust advancing “down” the globe in narratively convenient accord with lines of latitude: communications dropping out from Cairns, then Townsville, then Alice Springs and Rockhampton going dark as the deadly winds cross the Tropic of Capricorn.

There are debates about whether to evacuate to Tasmania or New Zealand, in order to buy a few more days. (Such debates persist, sixty years on.)

One stifling night my over-the-fence neighbors entertain a loud, obnoxious friend. We’ll call the friend “Ray”—because that is his name—and for our purposes he serves neatly to embody this country’s willfully oblivious, unaccountable id. It’s too hot to close the windows, and for several hours I’m unable to read, or to think, for Ray’s voice booming in the base of my skull. Ray identifies as the one percent. His hosts, as he decorously points out, are of the ninety-nine percent, and this is the fundamental problem with their opinions. From the pulpit of their BBQ-equipped balcony he decrees:

“The sea is still full of fish! The food bowl is bloody fine! Everyone’s saying it’s all going to run out, it’s not going to run out. [Thoughtful pause.] And if it does run out, we’ll just evolve, Darling.”

But only cephalopods self-edit their genetic make-up at that rate, Ray. And the seas are far from full, unless we are speaking of jellyfish. If we evolve, very quickly, to eat jellyfish—Darling—then we might stand a chance. But we sure as hell won’t deserve it.

During the shooting for On The Beach, Ava Gardner was reported as saying that Melbourne was “the perfect place to make a film about the end of the world.” A quip the reporter later admitted as fabrication, but decades too late to cauterize a closely-nursed wound to the Melbournian psyche.

In the novel Gardner’s character—Moira Davidson, a wealthy grazier’s daughter—is brandy-fueled and apoplectic: “There was never a bomb dropped in the southern hemisphere,” she insists, falling against the chest of an American submarine Commander. “Why must it come to us?”

“You’ve got to take what’s coming to you, and make the best of it,” is the Naval stoicism offered by Commander Dwight Towers. (Towers, incidentally, only likes paintings “when they’re full of color and don’t try to teach you anything.”)

In Shute’s Melbourne, people crutch along through the final months propped on various forms of denial and fatalistic hedonism—plans made for untenable futures, plots for gardens and the harrowing of fields, gifts purchased for loved ones long lost to the hot zones (several pages devoted to Towers’ shopping expedition for a pogo stick for his young daughter, as he prepares for a reconnaissance mission to whatever remains of the U.S.).

The petrol supply is gone, of course, save a few precious cans buried in backyards. Electric trains and trams still run, and more resourceful Melbournians trick-out bicycles, or gut the heavy engine blocks from cars so their shells can be harnessed to stock animals.

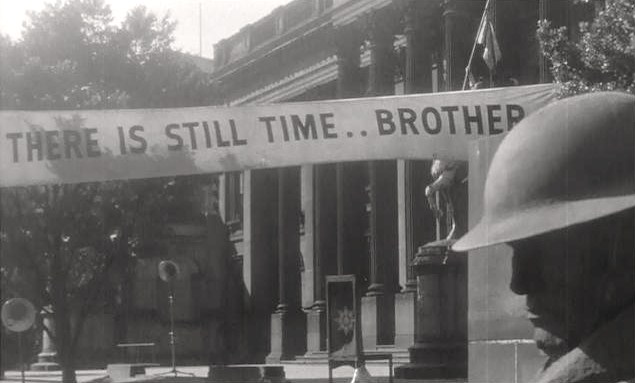

There are sudden conversions to religious cults, believers gathered on the lawn of the State Library under a banner that promises THERE IS STILL TIME .. BROTHER. There are sudden conversions to alcoholic oblivionism, fresh purpose discovered in diligently working through the last of “good” sherry before it is too late.

A reader comes to respect the undeluded outlook of the novel’s central alcoholics, in particular John Osborne—the fatalistic CSIRO scientist tasked with monitoring radiation levels, burdened by the Cassandra-ism that afflicts many modern climatologists.

“I’ve got it now. You’ve got it, we’ve all got it. This door, this spanner—everything’s getting touched with radioactive dust. The air we breathe, the water that we drink, the lettuce in the salad, even the bacon and eggs. It’s getting down now to the tolerance of the individual.”

Later in the piece, the sequestered fuel is dug up to death-race expensive cars in what promises to be the ultimate Grand Prix. For the meeker, there are orderly queues for government-issued cyanide capsules—“knock-out” pills, for when “this Cholera thing” gets really bad—and jokes about what to wash them down with: an ice-cream soda, a nice cold beer. People mothball their clothes as if readying for a long season away. They euthanize children and pets and livestock, or else open the gates on the pastures so the animals can fend for themselves. Then they shut down the power mains to mitigate the risk of post-apocalyptic house fire.

Shute was writing amidst Cold War anxieties, at the upswing of the Arms Race, as global nuclear testing was ramping towards its early 1960s peak of one detonation—somewhere in the world—every week, and Strontium 90 was turning up in the milk supply, concentrating in baby teeth.

Has there been, in the interim, a time so similarly propelled by dread?

When I was living in Upstate New York, I would habitually look up the blast radius of the world’s most cinematically destroyable city. Conveniently—also, troublingly; also, unsurprisingly—pre-existing diagrams are many and detailed.

Would we be able to get the kid, drive to Canada before—No.

In Australia, this particular annihilation scenario dims. The graphic representations are harder to come by. The home fallout shelter never took off here; even the seat of federal government lacks a final refuge. We are painfully aware of our insignificance, secure if somewhat self-conscious in the knowledge that nobody is particularly interested in blowing us up, that our cities (with the exception of a few iconic Sydney landmarks) would not crumple spectacularly, cinematically.

Stanley Kubrick once made detailed plans to relocate to Australia, ahead of the nuclear holocaust he believed was coming to his doorstep, going so far as to gain visas and steamer passage. In the end, he couldn’t stomach the more domestic horror of sharing a bathroom with strangers for weeks at sea, and instead stayed behind in the US to make Dr Strangelove.

At the time Shute was writing On the Beach (as somebody of Shute’s military experience was bound to be aware, and despite Moira Davidson’s sniffling) atomic bombs were being detonated in Australia, had been for some years, though they were being kept as far from public and media attention as realistically possible. Since the early 1950s the British government had been given clearance for nuclear weapons testing off the coast of West Australia, and later in the Great Victoria Desert in South Australia.

“England has the bomb and the know-how.” Howard Beale, Australian Minister of Supply (1955) “We have the open spaces, much technical skill, and great willingness to help the motherland.”

The ongoing program of nuclear colonialism was conducted with what a Royal Commission would later deem “an almost paranoid obsession with security and secrecy,” to the extent that authorities often neglected to forewarn those living within the immediate fallout zone.

But it is difficult to conceal a mushroom cloud. Still more difficult to contain one.

Fallout from the tests carried as far as Adelaide, Melbourne, Hobart, Canberra, Sydney, Brisbane, and Darwin, effectively contaminating the entire continent. The 1984-85 Royal Commission found that it was “probable that cancers which would not otherwise have occurred have been caused in the Australian population.”

But those at greatest risk of exposure were the local Indigenous communities living close to the land—the red dirt and spinifex grass that the colonial eye conveniences as nothing, nowhere, despite the fact that Indigenous people had been traversing and living from these plains long before white arrival and white record keeping, and would continue to after contamination.

Australia Day, January 26th, still commemorates the date of white arrival: Invasion Day. A friend and I spend it in the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges, at the Burrinja art gallery, who are hosting the final weeks of Black Mist Burnt Country—a two year, nationwide exhibition marking the 60th anniversary of the British atomic test program at Maralinga in South Australia.

The titular Black Mist refers to numerous testimonies of a greasy black miasma, which blew from the blast sites into nearby communities, coating leaves, food, clothes, skin, setting in a toxic scum over water sources, and ultimately resulting in symptoms consistent with radiation poisoning.

Black Mist Burnt Country brings together thirty-eight Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists. Two portraits show Yami Lester, a Yankunytjatjara man who became a staunch campaigner for the victims of atomic testing. A child at the time of the Maralinga tests, Lester recalled the ominous black cloud approaching from the southwest, moving like a dust storm but eerily quiet. The result of this witnessing was acute sickness, and a burning in the eyes that would quickly lead to lifelong blindness.

In the first portrait, Maralinga—a holographic lenticular by Belinda Mason— Yami Lester’s right eye is wide open, tracking the viewer, sight beyond sight. (His left was removed shortly after his exposure to the Maralinga fallout.)

In a second, starkly contrasting portrait, Lester stands with both eyelids closed, his teeth gritted, as if bracing against an unseen force, or calling upon deep reserves of fortitude. The photographer, Jessie Boylan, also did an extensive portrait series on Avon Hudson, an RAAF ex-serviceman, and a key whistleblower who admitted to helping bury twenty-six boxes of radioactive plutonium waste under three meters of sand.

Clean-up efforts from the 500+ tests were so cursory as to be callous, and for many years after, people moved through and lived from these areas, heedless to the foreign (i.e.; english) warnings on sparsely-posted prohibition signs. For many years after, animals grazed near here, were hunted for food, and the red soil sparkled with a strange green luster.

Among the exhibition’s most striking works is one of the simplest. In Mick Broderick’s Counts Per Minutes (CPM): Alchemy, two large glass petri dishes sit atop a plinth, one filled with red Maralinga soil, the other with atomic glass, fused and transmuted, collected from ground zero.

The typical accompanying gallery signage is imbued with disquieting irony:

—Do Not Touch—

Mahogany is not a color you want to see on the temperature map. What it indicates in Celsius is around 46 degrees, or 115 Fahrenheit. (In 2013 the Australian Bureau of Meteorology had to add a new color to the temperature map—an incandescent, Byzantium purple—to illustrate 52-54 Celsius, or 125-129 Fahrenheit.)

In early January, the New South Wales town of Menindee swelters through four consecutive days of 47 celsius. After which, the thermometer in the local Post Office breaks. A cartoonish depiction of climax—the distended glass and a bright red burst of mercury. In the days that follow, an estimated million fish die, essentially suffocating in the shallowed-out, algae-choked waters of the Darling River—part of the most significant water system in Australia—drained and diverted for irrigation, illegally siphoned off to fill the vast reservoirs of cotton farms despite being thinned to a trickle by drought.

It is biblical imagery, and media footage confirms as much as the mind might conjure; innumerable silver bellies turned skyward, carpeting the surface of the river. Golden and silver perch, tiny bony bream. Close-ups of massive Murray River cod—30 or 40 or 50 years old—being piled into the tray of a utility bring home the sickening reality of clean up efforts, in what comes to be hashtagged as the Menindee #fishkill.

The heat spikes again over the coming weeks. The scene at Menindee repeats. At the same time, bushfires roar across Tasmania, many triggered by dry lightning strikes, a phenomena that until recently was a rare occurrence. Tasmania right now is just wind and smoke, a friend tweets from the island state which still holds appeal in the global and national imagination as some kind of last harbour. The accompanying clip shows the hazed sky as bushfires engulf huge tracts of World Heritage forest, along with endemic species found nowhere else on earth.

In weeks ahead, southerly currents will carry the smoke across the Bass Strait towards Melbourne, tinging the air with the smell of ash, and bringing a violet-orange cast to the sunsets.

There was a point early in December, during weeks of unseasonably grim weather, when people (people like my father, people like Ray) took to cheerily bellowing, SO MUCH FOR GLOBAL WARMING, HEY!

But this January has been the hottest month in Australia’s written history. Following what turned out to be the hottest December on record.

There is a broken-record feeling about all this record-breaking heat.

In the regional town where my older sister and her family live off the grid, on solar and tank water, and nothing approaching air conditioning, her teenaged children drag mattresses onto the decking to sleep overnight, cocooned in mosquito nets. Wet sheets are hung in doorways to cool whatever breeze might come.

Two-minute showers, bushfire survival plans, snake identification charts: these are, for the greater part, active choices, the pre-calculated costs of living with lessened impact. Vigilance, or what might simply be termed awareness, an appropriate way to exist within one’s environment.

However most of us are only able to imagine significantly adapting our lifestyles through force of necessity, when all familiar and comfortable alternatives are extinguished. Even if we wholly believe in the moral imperatives; even if the moral imperatives are loud and clearly broadcast from our bookshelves. We still want what we want, which has a lot to do with what the next person wants; cars and kids and air travel and produce out of season, devices that both anticipate and engineer our wants.

“If I could press a button that would wipe out all humans instantaneously, I would do it,” a friend tells me casually over coffee (a catch-up that has been postponed three times due to fingernail curling heat). “Just as long as I could be sure there weren’t some super-rich bastards hiding in a lair somewhere.”

Fifteen years ago, Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term “Solastalgia” to convey “the homesickness you have when you are still at home”—a melancholia and longing felt for an environment that has been dramatically altered, desolated.

Solastalgia has since come to be widely adopted as a watchword in the global lexicon of existential crises brought about by environmental crises.

Less-quoted is Albrecht’s more recent neologism “soliphilia,” meaning the love and responsibility to place, interconnectedness and accountability necessary to maintaining its vitality.

The more famous term is elegiac; it offers precise language to an ever more prevalent form of existential anguish.

The latter—soliphilia—implies not only agency, but onus; the ongoing imperative for guardianship. It denotes symbiosis, and through that, culpability. Albrecht created it “as a cultural and political concept that will help negate dread and solastalgia.”

How do we remain cognizant of this great diminishing, our ever more compromised and lonely future, without living in a daily tenor of requiem?

Or, because that might not be entirely possible if we are paying attention (short of dedicating ourselves to wasting not the good liquor), how do we live in this register of exponential loss whilst remaining vitally accountable to what remains?

As with the philosopher, this might be the essayist’s instinct to leave the window open a crack.

In the closing scenes of On the Beach, the major thoroughfares of central Melbourne are entirely depopulated. Trivia or apocrypha?—that director Stanley Kramer simply went out with the camera crew on a Sunday morning, before everyone in town was awake.

The city is about three million greater than it was sixty years ago, though the truly savage days—the mahogany days—still have this desolate quality. When the city wavers in heat-shimmer, airless as if domed over by thick glass, and there are media-issued warnings to stay indoors. You coulda fired a canon down Bourke street.

Sometimes when passing the State Library, I find myself superimposing a detail from the film’s final shot; the evangelical banner still strung before the building’s roman columns, flapping alone in nuclear wind, There Is Still Time .. Brother, promising a world beyond the one we’ve just scuppered.

A longer-reaching, albeit non-anthropocentric line of optimism is voiced in the novel by Shute’s harrowed scientist John Osborne:

“It’s not the end of the world at all,” he said. “It’s only the end of us. The world will go on all the same, only we shan’t be in it. I dare say it will get along alright without us.”