An a cappella “’O Sole Mio” echoes along a Venetian canal. Che bellacosa na jurnata ‘e sole, N’aria serena doppo na tempesta. A sunny day is such a beautiful thing, the air is calm after the storm.

The song is from Napoli, but tourists prefer it to a traditional gondolier’s barcarolle. These canals stay the same depth, no matter the tide. The street lamps glow and the clouds convey the soft colors of dusk whether it’s 10 a.m. or 10 p.m. A plaque affixed to the ledge of a stone bridge reads, This feature is operating in compliance with the drought ordinance. A water efficiency and drought response plan is on file with the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

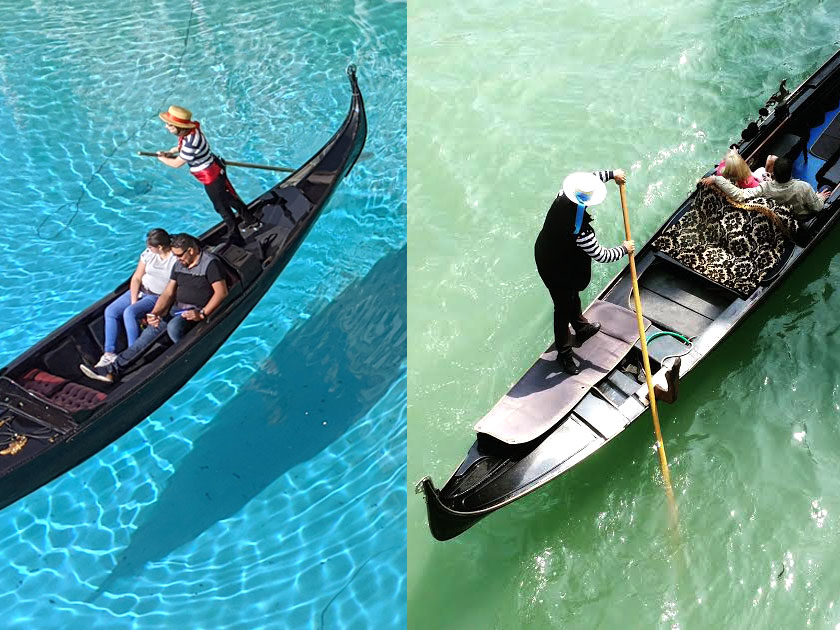

The singer, in her gondolier stripes and straw hat, tells me her name is Gabriella, of Sicily, and that she worked as a baker in Chicago before moving West and finding this gig as a singing gondolier at The Venetian, a 1.5-billion-dollar, several-thousand-room resort and casino on the Las Vegas Strip, built by the late Sheldon Adelson. “It’s easier to teach someone to steer a boat than it is to teach them to sing in Italian,” she says. Tourists can ride indoors or out and be serenaded in Italian or English, their choice. At about $30 per person or $116 for all four seats on a ten- to twelve-minute cruise, floating with Gabriella through the resort’s mall is generally more expensive than the cost of hiring a gondola in actual Venice.

On a spring morning in 1999, the Venetian threw open its doors for the first time, greeting the world with a chorus of trumpets. A flock of white doves-for-hire flew into the air above smaller, newer, but meticulously accurate Venice landmarks, including a Campanile Tower just eight feet shorter than the original (to accommodate a helicopter flight path). Beneath a faux Rialto Bridge, in an inordinately cerulean network of canals, Sophia Loren christened the inaugural journey of the motorized gondola fleet. A bystander observing those 850,000 gallons of water would never have known Southern Nevada was at just the front edge of a several-year drought. Many of the rooms and most of the restaurants were not yet complete, and Culinary Union 226 was staging picket lines on the sidewalk under threat of arrest, but Adelson and his Las Vegas Sands corporation refused to let anything rain on their parade.

It’s on November 12, 2019, while I’m checking into my travel-deal-site room at The Venetian, that the real Venice reaches its peak tidal flood stage—acqua alta eccezionale—for the fifth time in a year, beating its previous high tide annual record of twice in a year. When I touched down at McCarran International Airport this morning, the water in Venice had already begun to rise, and by mid afternoon, as I marvel at Adelson’s partial replica in Vegas, the sea is coursing through Venice’s streets.

“So, see these two columns over here?” asks Chiara from Calabria, a gondolier who also gives hour-long art tours at the resort. “These make up the gateway to Venice. They were taken from Constantinople in 1172—”

“These actual columns?” I ask, “Or—”

“Not these ones, the ones in Venice,” she says before leaping into a gripping story of their history and why the space between them is so unlucky. I would not have put it past the hotel’s creator—billionaire casino mogul, Republican Jewish Coalition supporter, and unrivaled super PAC donor Adelson—to source granite columns from 12th-century Constantinople for this project. He wasn’t here to build a fake Venice: “We’re going to build what is essentially the real Venice,” he told Casino Journal in 1997. When he couldn’t get the Botticino marble for the hotel lobby’s flooring at the desired price or pace he needed, he acquired his own quarry in the Alps. This fell right in line with Adelson’s reputation for buying most anything he wanted, including an Airbus A340, a 300-foot superyacht, eight mansions in Malibu, the Las Vegas Review Journal (along with his rumored influence over the paper’s editorial position on certain issues, i.e. stories about himself), not to mention sway over various elections, and over the former president Donald Trump, for whom Adelson was known as “Patron in Chief.”

In 2012, Adelson and his wife Miriam Adelson—a doctor devoted to treating recovering drug addicts—contributed at least $98 million to Republican candidates, and they gave $20 million to a pro-Trump Super PAC in 2016, plus $5 million for the inauguration. That year they also matched the value of the coins tossed in the Venetian’s indoor waterfall feature as a donation to the Adelson Clinic for Drug Addiction Treatment and Research. Accordingly, in 2018, Mrs. Adelson, who oversees the clinic, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor.

Chiara is explaining to me that in Venice, the Bridge of Sighs is so called (first by Byron) because it connected the court chambers of the Doge’s Palace with the new prison, or Prigioni Nuove. Some editorial license was taken with the one we stand in front of now, which instead bridges the palace to the house of the woman who inspired Shakespeare’s Desdemona. “Much nicer!” she says.

We walk toward St. Mark’s Library. “This was designed by Jacopo Sansovino, a refugee from Rome,” she gestures to the library’s top level, continuing an impressively disorienting conflation of our current situation on this four-mile stretch of opulence in the Mojave Desert and the imagined situation of walking through Venice itself. “The library is all on that top floor because you know there’s a lot of flooding, and we don’t want all those precious manuscripts to get destroyed.”

We step onto a moving walkway over the faux Rialto. “Here we don’t have any library but we have a Sephora—a make-up library.”

The building also contains a Madame Tussauds, which Chiara prefers to the Hollywood version—it’s cleaner and more updated. Vegas likes that—no shortage of Tripadvisor reviews joke the Venetian has the leg up on the original, centuries-old island city when it comes to pigeons, and the smell, and Travelocity lists a whole seven reasons the Venetian is “way better than” real Venice. You can swim in its water, for one.

As a moving walkway spills us onto an escalator, Chiara insists I look up and admire the detail in the stonework around us. “So you can really be immersed,” she says over the noise of a man in a headset announcing discounts for the wax museum. At the foot of the escalator, we’ve come full circle to face the Doge’s Palace, a whole-hearted recreation of the 1340 edition. Obscuring a swath of its façade is a two-story-tall banner for the Venetian’s Atomic Saloon Show, a permanent-installation cabaret that promises cowboys in assless chaps, pole dancing, and acrobatic nuns.

Back in my suite (every room at The Venetian is a suite), the television is on and tuned to the resort’s channel. “We’ve created an ice bar in the middle of the Mojave Desert,” the voiceover exclaims, “the only place in Vegas where your beer gets colder as you drink it.” The camera pans over a room built out with ninety tons of ice, coating or constructing everything but the floor and the ceiling and kept at a steady negative five degrees Fahrenheit. Patrons of all ages laugh and toast in bar-issued parkas and fun animal hats.

Some forty miles away, Lake Mead—the Colorado River reservoir on which Las Vegas heavily relies—hovers around 40 percent full. Flying over the state this morning, the bathtub ring around the lake glowed white on brown, and the edges of the city carved into the flat desert looked like settlements on Mars. In late 2019, to avert a federal water shortage declaration, these states entered into a voluntary drought contingency plan, which is still in effect during my visit.

Las Vegas is a diverse city of 2.2 million people. The Strip—a synecdoche for the city to the outside world—is not only not representative of daily life in Las Vegas; it’s not actually in Las Vegas. Rather, it lies mostly in an unincorporated place in Clark County called Paradise (living up to its name for casino owners, who are exempt from city taxes). In Paradise, Nevada’s persistent drought is invisible. Along its thoroughfare, lakes sparkle and fountains shoot forty stories into the air. Visitors scuba dive with sharks, feed sea turtles, swim with dolphins. The obsession with water is so entrenched here, Adelson wasn’t even the first to dream up the desert-bound waterways of “Las Venice.”

In 1991, the Chicago Tribune reported, “Although Las Vegas is experiencing drought conditions so extreme that a violation of the sprinkling ordinance can carry a six-month jail sentence, a consortium of casino owners hopes to fill parts of downtown’s three busiest streets with water and float gondolas on the resulting twenty-two-foot-wide canals.” Nearly a decade before the Venetian’s grand opening, Steve Wynn—#MeToo’ed Trump-era R.N.C. finance chairman and Mirage casino mogul—spearheaded this 25-million-dollar canal proposal, which originally suggested sourcing necessary water from the drinking supply before pivoting to recaptured run-off to mitigate bad PR. Interest in Wynn’s plan dried up, but that same year Sheldon and Miriam Adelson were married and would honeymoon in Venice, Italy. By the end of the decade, canals in Las Vegas would become a reality.

The true extent of the water crisis in Southern Nevada is hard to define. For every set of data supporting a dire water shortage in the near future, there is a news story commanding readers, “Forget everything you’ve heard about Southern Nevada’s water crisis.” These mixed signals spring from the fact that understanding the region’s water supply involves seeing the future, and not everyone shares the same vision: rising temperatures, more evaporation, less rain, more wildfires, earlier icecap snowmelt in greater quantities per season, less snow to replenish the ice caps, not to mention sea-level rise, human migration… The last two summers, Nevada broke records for consecutive days with temperatures over 105 degrees and the trend may well continue. All of these factors make modeling the future of water in Southern Nevada impossible to foretell.

In this context, flamboyant water use on the Strip may seem irresponsible. But water planners say its impact is negligible and in fact, the Strip’s casinos have been hailed for their leadership in water conservation. According to the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA), the major casinos recycle an average of 40 percent of their collective few billion gallons per year—twice the recycling percentage of the city overall. As one of the world’s largest LEED-certified resorts, the Venetian in particular uses filtration and cooling technology to, according to its website, save or recycle tens of millions of gallons annually while working to decrease its year-over-year usage, even with its thousands of bathtubs, quarter mile of canals, and eleven swimming pools.

Taking that into account, local and state governments would strongly prefer not to mess with Paradise, whose water spend is also measured against its benefits: In 2019, the $67.6 billion-dollar gaming and tourism industry provided more than a quarter of all employment in the state of Nevada and close to 40 percent of the state’s general fund revenue. Rather, the SNWA would much rather focus on regulating residential water use, which they say takes the lion’s share of the region’s draw on Lake Mead.

At the time of my visit to Paradise, the Adelson household uses more water than 99.99 percent of other Las Vegas households—some 135 times the median annual household usage. (Indeed, their 44,000-square-foot, twenty-bathroom home has its own waterpark). But the family’s most notable impact on Nevada’s desertification and on the real Venice’s inundation was their financial support of the Trump campaign.

At the start of 2020, the Bureau of Reclamation under Trump began fast-tracking a controversial pipeline plan to carry water out of Lake Powell, a Colorado River reservoir that releases some water into Lake Mead each year. Meanwhile the administration enacted more than 170 actions toward federal climate deregulation since 2017, according to Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. Every concession on emissions accelerates the fate of climate-vulnerable places like increasingly hot and arid Nevada—and increasingly waterlogged Venice.

Tonight, while guests of the Venetian gather in the ice bar, some parts of Venice are six feet underwater because of a weather event: a cocktail of tides, storm surges and winds that are no longer a rare combination, and that, even following the July 2020 opening of MOSE, still pummel the city’s delicate architecture multiple times per year.

Also working against Venice, especially in the long view of gradual sea rise, is that it is also sinking an estimated millimeter or two per year, in part because the groundwater was pumped out from beneath the city in the mid-20th century.

As I fall asleep, Venice’s Mayor Luigi Brugnaro is posting to Twitter: “Venice is on her knees,” adding later, “These are the effects of climate change… The costs will be high.”

Among Sheldon Adelson’s life achievements, he built not one but two counterfeit Venices. In Macau in 2007, he opened what was then the world’s largest casino, the $2.4 billion Venetian Macao. In December 2019, Las Vegas Sands’ share prices rise by nearly four percent as Trump tweets optimism about a trade deal with China. This boosts Adelson’s net worth by an estimated $1.2 billion in a single week.

Meanwhile, it is the end of Venice’s worst year of flooding in a half-century. During its worst acqua alta eccezionale, the city suffers €1 billion in damages, including €360 million in urgent repairs to municipally owned property and infrastructure, like walkways, streetlights and vaporettos.

After leaving Las Vegas, I dig up an online Venetian Gondolier job posting, listed by BESTAgency. Among the requirements for the non-union, on-call, day-to-day position of Gondolier at the Venetian are:

- “Must be able to sing and project in a cappella;”

- Must “enjoy interacting with guests and visitors while operating a gondola;”

- “Must be able to swim;”

- Must “create an Italian character and learn various pre-approved Italian songs.”

Anxiety washes over me: Were the gondoliers I met Italian, or were they in “Italian character”? Was Gabriella’s accent real? Did Chiara grow up in Calabria with the dream of defying gender barriers to become a gondolier like she told me, so charmingly, in the fake Palazzo? Was her name even Chiara? Had I been conned?

Is it even possible to set foot in Las Vegas—or rather, in Paradise, Nevada—without being conned?

In 1638, a gambling casino sanctioned by the city of Venice and known as il Ridotto opened in a private home in Venice near the Chiesa di San Moisè. It is understood to be the world’s first legal gambling casino, where masked Venetians of all classes mingled freely. Men and women, nobles, foreigners, priests, rabbis and thieves were gripped by a fever to gamble, and masks—though the city council tried in vain to outlaw them—were critical to the practice. Gambling—especially with an element of anonymity—was the great equalizer, writes James H. Johnson in Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic. Becoming the selves Venetians could not be at home, what happened at the casino stayed at the casino.

While visitors I talk to are genuinely awed by the opulence of The Venetian, the feat and scale of its artifice, the charm of its Italian characters, there is a perverse irony in knowing that Venice, after all, was the first Vegas. Who is the con now?

The day I spend at the Venetian, like any other day, some 50,000 tourists, gamblers, conventioneers, and travel influencers shuffled through its labyrinthian food courts, shopping areas and casino halls. In a miniaturized Piazza San Marco, they buy gelato, gnocchi, Sangiovese, tiramisu, and—according to the afternoon bartender at Canaletto’s—so many Aperol spritzes they flow from the bar “like water” to the sounds of an operatic performance of “Funiculì, Funiculà” repeated every hour on the hour, put on by jesters and a clown on stilts in clean new versions of old-world dress.

On account of a full moon and strong winds in real Venice, the high tide that November night takes two lives. Water surges through the alleys and pours through shop windows as if from a broken dam. In the following days, schools close. Vaporettos wash askew onto sidewalks. Women with Louis Vuitton bags wade through the real Piazza San Marco thigh-deep in turbid seawater. A priest and the mayor stand crestfallen and up to their shins on the inundated mosaic crypt floors of a basilica that dates to 1563. Far from the seemingly steady, clean canals of the desert oasis, things in real Venice are all too real. And forty miles from Lake Mead, in an oasis in the Mojave, those buying into Adelson’s Venice are none the wiser.