In the early 1940s, a full two decades before French intellectuals identified postmodernism as a self-reflexive, intertextual, metahistorical, and metafictional way of approaching art, literature, the media, and the world at large, America seemed on the verge of beating them to the punch.

After the mayhem, violence, widespread poverty, political confusion, and paranoia that marked the first decades of the 20th century, from an American perspective, the world had suddenly become a much more complicated and absurd place. The First World War, the Great Depression, the first Red Scare, Prohibition, the rise of Hitler, and the slow, inevitable build-up to World War II had all taken their toll on the national psyche. The results were only exacerbated as Dadaism, Surrealism, and Freud began quietly infiltrating the mainstream.

The idea of a consciousness that could represent a chaotic and densely interconnected world was reflected early in European literature, music, and painting via the likes of Joyce, Céline, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Picasso, and many others. What constituted meaning and narrative were not only being questioned but, in certain circles, tossed out the window. It took a few more years for these ideas to filter down to a more low-brow crowd.

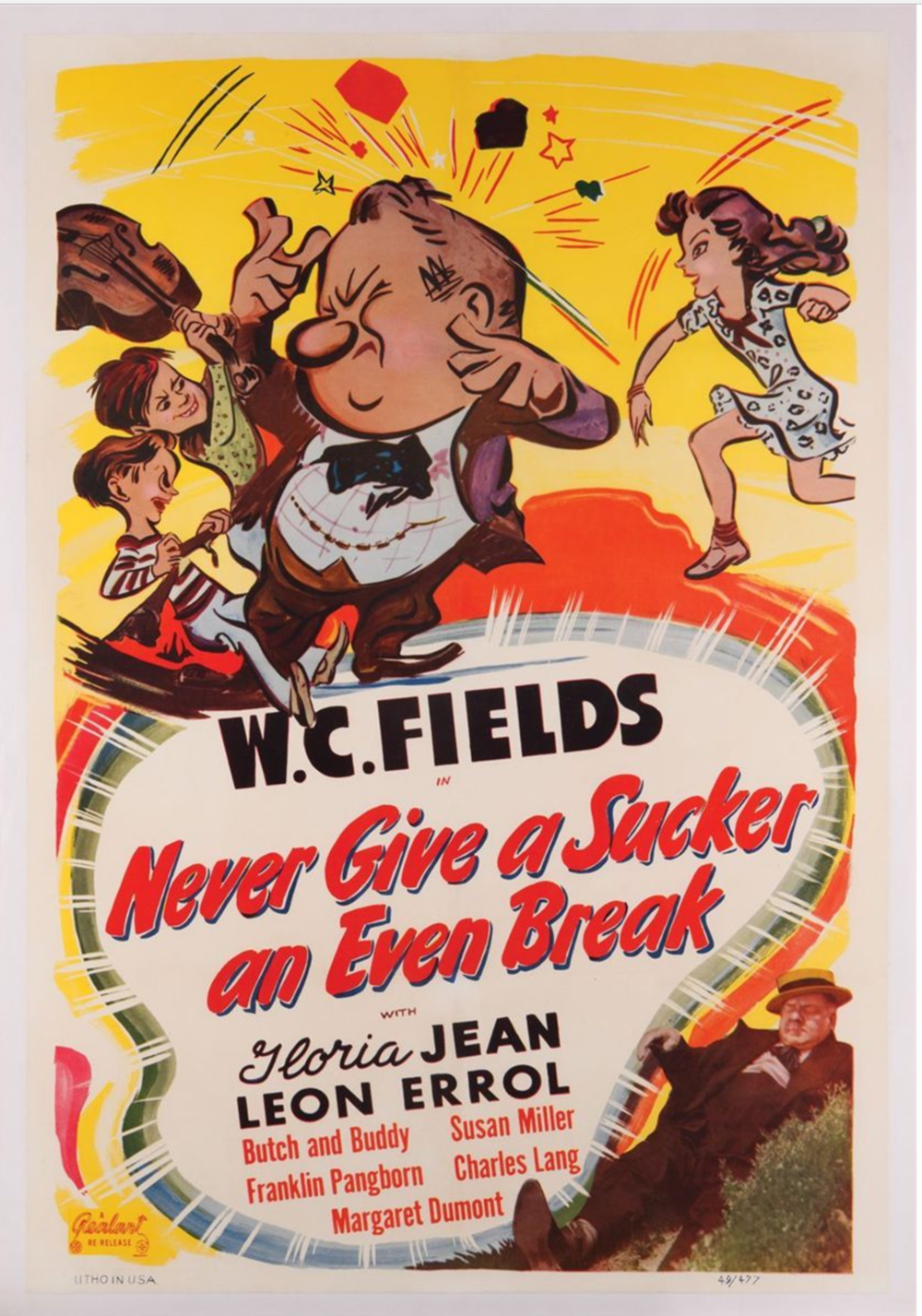

In American popular cinema, this growing perception of the world was beautifully, if crazily and sloppily, expressed in what would be the last true W.C. Fields film, 1941’s Never Give a Sucker an Even Break. With drinking taking an increasing toll on Fields’ reputation within the industry (as well as his ability to perform after noon), Fields wrote a film in which he plays himself as a once-respected comic giant who no longer gets any respect from anyone. Worse, it’s clear his once-sharp talents are beginning to fade.

Sucker is a film painfully aware not only of its star’s offscreen persona, but one also deeply conscious of itself as a film, and a film within the context of a much broader movie industry. It cuts seamlessly and without warning between Fields’ efforts to pitch a new script to an increasingly reluctant producer (Franklin Pangborn, also playing himself), the actual (awful) film that would result from the script the producer is reading, and Fields’ niece’s attempts to rehearse a song for still another film while a set is being built around her. In the process Fields breaks the fourth wall to complain about the censors. He toys with the myth of fame, and lays bare the muddy mechanics of the movie industry, deliberately leaving audiences confused and dissatisfied with an ending that’s hardly any ending at all. The film may have seemed to some audiences and critics a gloriously unholy mess, but Fields knew exactly what he was doing, and became the first major figure at a major studio to present mainstream American audiences with a stab at a metanarrative.

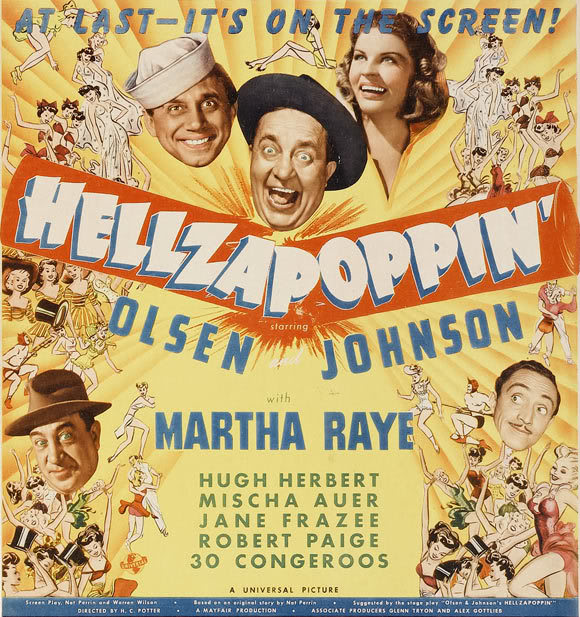

Three years earlier in 1938, the comedy team of Chic Johnson and Ole Oleson wrote, produced, and starred in the vaudevillian musical comedy revue Hellzapoppin’ on Broadway. Hellzapoppin’, essentially, was a musical within a comedy within a vaudeville show within a stage play. The stage play itself is a profoundly self-conscious act, clumsily acted out in front of a live audience by actors with their own off-stage lives. In and amongst the jokes, the songs, and the dance routines, there were running gags, audience plants to help shatter the fourth wall, and an ongoing, absurdist, behind-the-scenes satire of theater itself.

Hellzapoppin’ was a massive hit, running for an astonishing three years before Universal decided to turn it into a film (itself conscious of the fact it was based on a popular stage play). The tricky part was translating all those gags involving the nuts and bolts of a theatrical production into cinematic terms.

Released two and a half months after Never Give a Sucker an Even Break, Hellzapoppin’ was more frenetic, manic, and a more perfect expression of what would later come to be known as postmodernism.

Directed by H.C. Potter from a new script by Nat Perrin and Warren Wilson, Hellzapoppin’ opens with an irate and confused projectionist (Shemp Howard) spooling the film and setting it rolling. The movie we’re watching flashes onto a screen within the movie we’re watching. As a chorus begins singing the jazzy, up-tempo title song, they seem poised to break into a lavish production number. Then the stage gives way and they’re all abruptly dumped into Hell, where they’re set upon by demons as the one-liners and sight gags start to fly, interrupted by shrieks and explosions. Chic and Ole, as themselves, arrive in a cab, and the camera pulls back to reveal Hell is just another Hollywood soundstage. Chic and Ole then begin arguing with the projectionist who, despite insisting such things simply can’t be done, eventually relents to their demands, rewinding the film we’re watching to the previous scene.

Three minutes in and the film already has the audience off-balance, self-consciously taking several large steps outside the expected fantasy, deconstructing the fundamental notion of the standard Hollywood entertainment. This move is only pushed further when Chic and Ole drag out the film’s suspicious and near-catatonic screenwriter (Elisha Cook), demanding he add some kind of love interest to the goings-on. Cook argues it makes no sense, it’s not part of the film, but they again insist, simply because every film ever made has to include a love interest. He goes away, and sure enough, ten minutes later a love interest works its way into the otherwise nonsensical proceedings.

Meanwhile as the bad jokes and visual gags and film references continue to pile up, a young deliveryman repeatedly wanders through the set/film, trying to deliver a plant to one “Mrs. Jones,” and another woman likewise wanders through the set/film in search of her husband Oscar. Chic and Ole move to another location and start watching the film they’re making/starring in (which again, of course, is the film we’ve been watching), musical numbers crop up unexpectedly, and in reaction to the constant bickering and demands, the projectionist starts screwing with the film itself, rocking the image and freezing it between frames, leading to more bickering between multiple Chics and Oles. (A number of the film’s gags would be lifted quite consciously and reappear in later Warner Brothers animated shorts.)

Meanwhile within the sort-of story which bridges the gap between the anarchic production and the film itself, a screwball love triangle works itself out and a disastrous piece of musical theater is pulled together and staged for potential backers who could send it to Broadway. Also, in a reflection both of the structure of Hellzapoppin’ and the idea that would lay at the core of Jean Baudrillard’s entire career a couple decades later, Mischa Auer plays a real Russian nobleman who pretends to be a fake Russian nobleman, simply because people find artifice more interesting and entertaining than authenticity.

It was clear in both Never Give a Sucker an Even Break and Hellzapoppin’ that a new kind of consciousness was afoot and reaching the mainstream public, a new way of understanding the world and the culture, one that telescoped history and meaning, dissolved the distinctions between the highbrow and lowbrow, and intertextualized medium and message into a singular (if messy) continuum. As absurd, complex, confusing and chaotic as it all was, mainstream audiences seemed to be gleaning onto the fact this reflected what the world and the culture were like now, so it was best to approach and accept it as such.

In what was perhaps the biggest postmodernist joke of all, Hellzapoppin’ received a Best Song nomination at the 1942 Academy Awards for “Pig Foot Pete.” Only problem with that was the song actually appeared in the Abbot and Costello feature Keep ‘Em Flying, which was produced by the same team behind Hellzapoppin’, but released a month earlier.

Well, then, between the October 10 release of Never Give a Sucker an Even Break and the December 26 release of Hellzapoppin’, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United States officially entered World War II, and the world, in a blink, suddenly became very simple and comprehensible once more. There were Good Guys and Bad Guys, clear and distinct borders, and the nation had an unquestionable mission to restore order and maintain the status quo as it had been generally understood. Self-awareness and dense intertextuality in film would be lost and forgotten, and would remain so for the next two decades, at which point the French took full credit for recognizing it.

Jim Knipfel is the author of Slackjaw, These Children Who Come at You with Knives, The Blow-Off, and several other books, most recently Residue (Red Hen Press, 2015). his work has appeared in New York Press, the Wall Street Journal, the Village Voice and dozens of other publications.