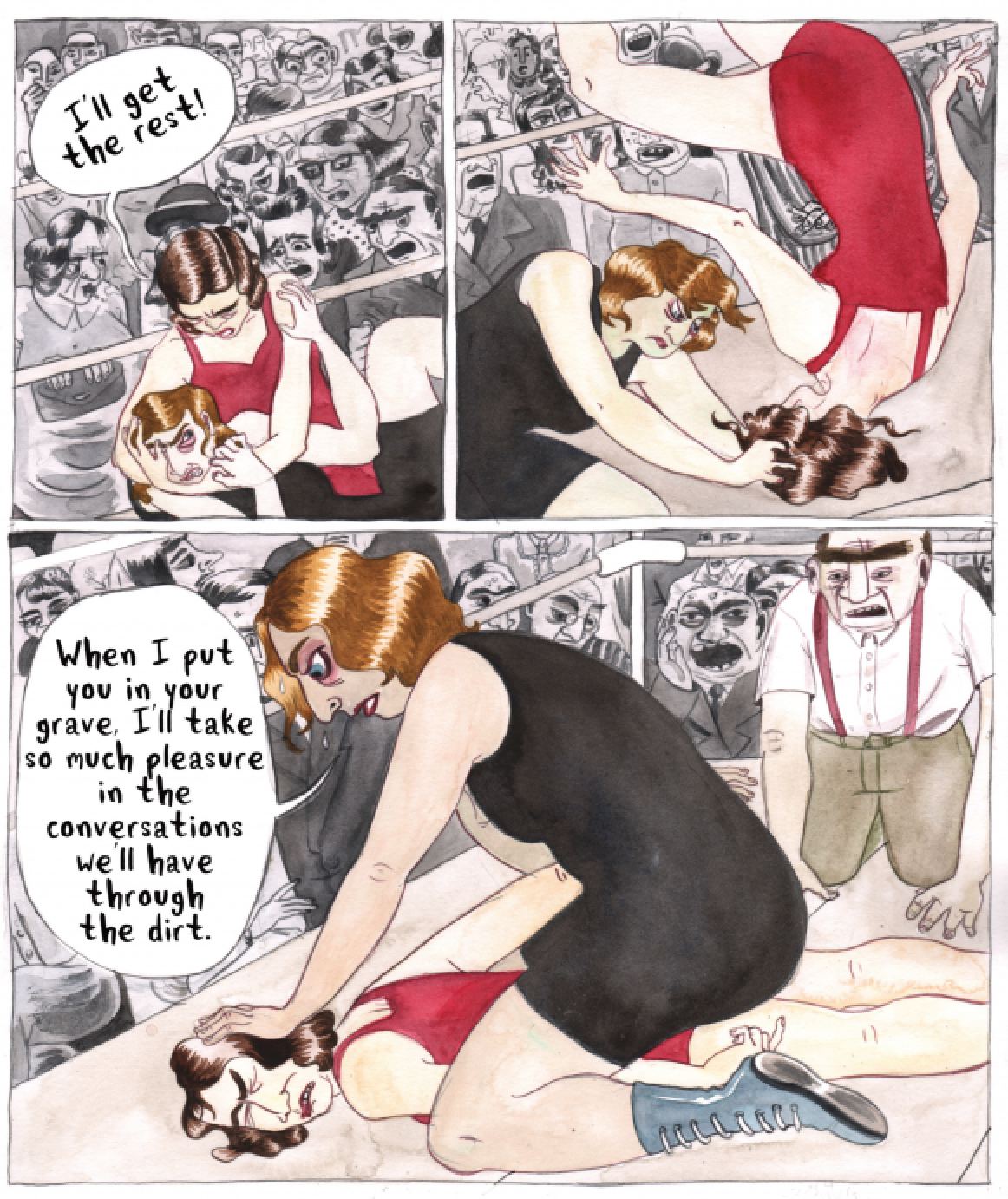

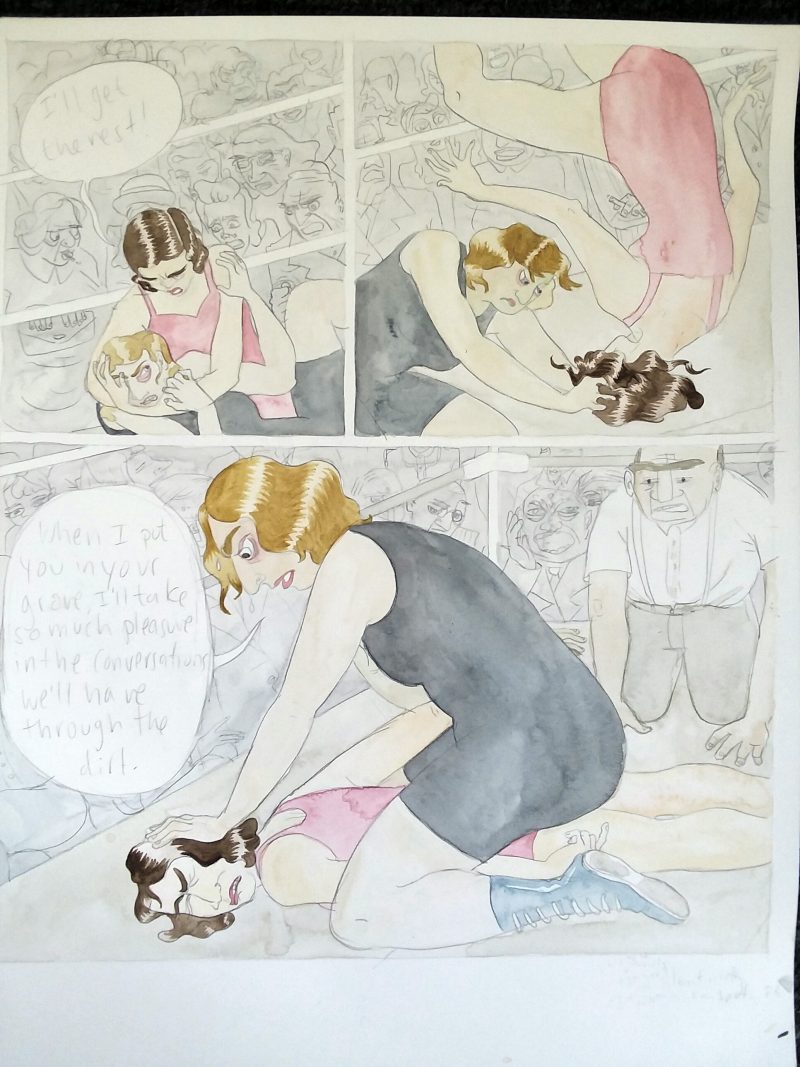

Nobody draws figures quite like Leela Corman—radical and hyper-stylized, her characters belong to a different, more beautiful world than the one we inhabit. Here, she discusses the making of “Kraut,” a graphic narrative about ghosts, trauma, and women’s wrestling after World War II.

—Kristen Radtke

THE BELIEVER: How did this comic start?

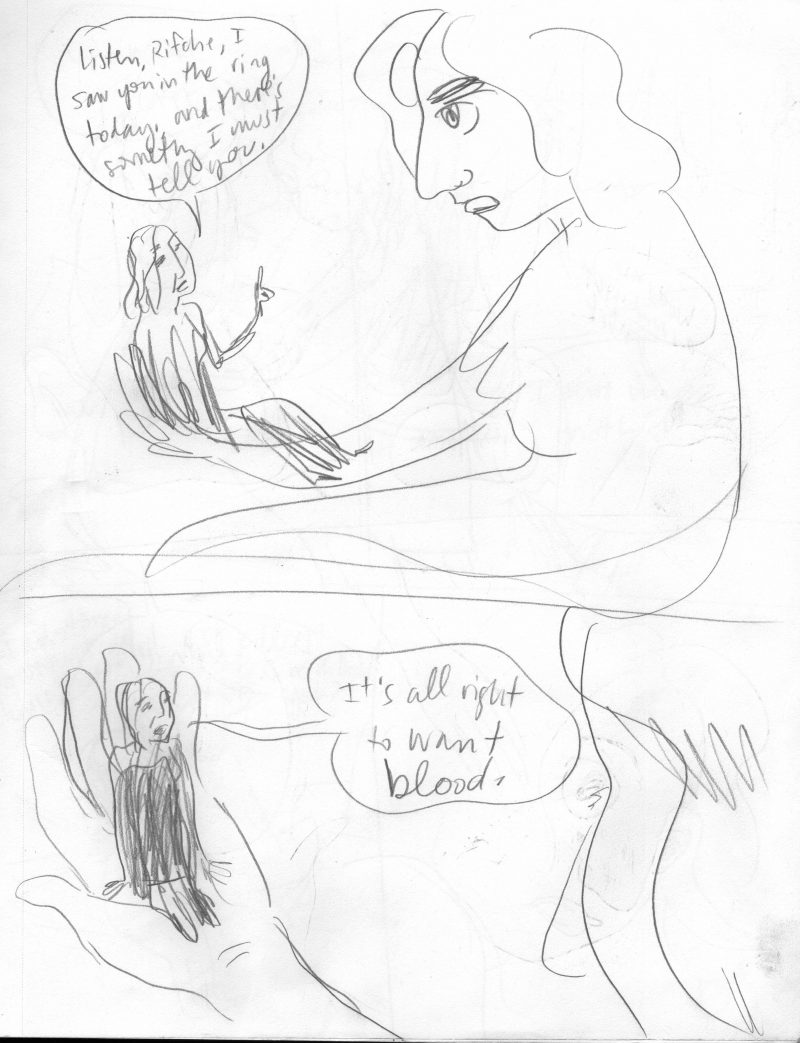

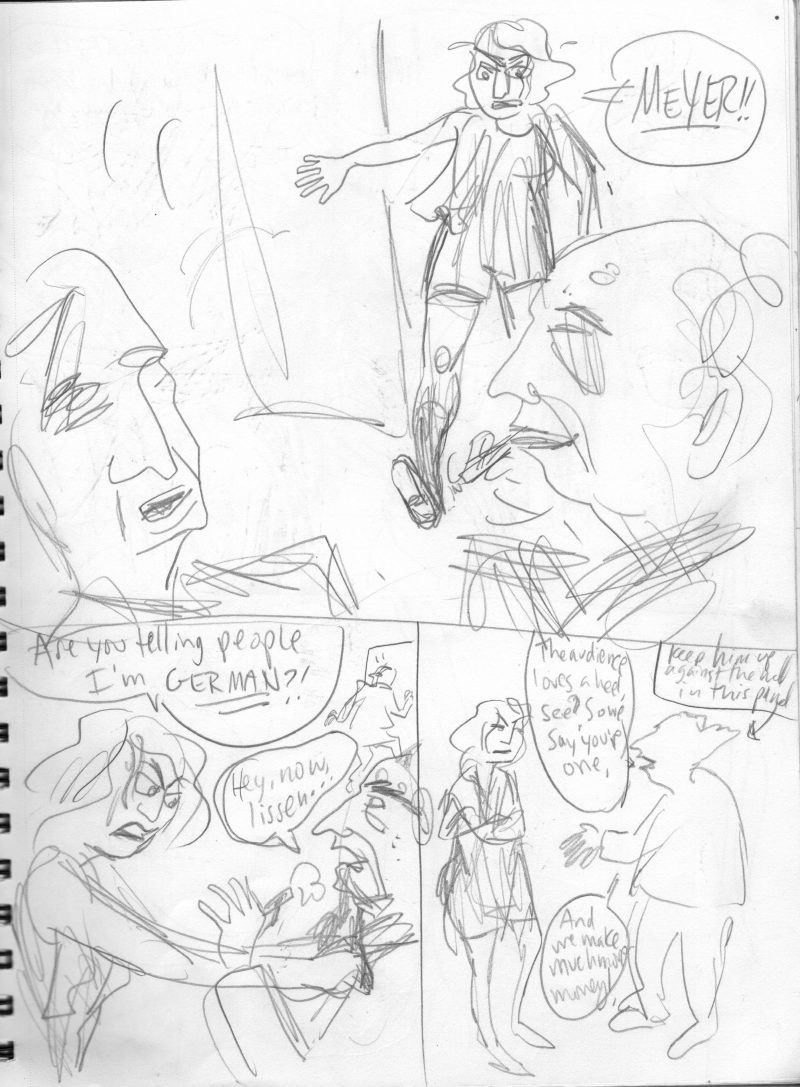

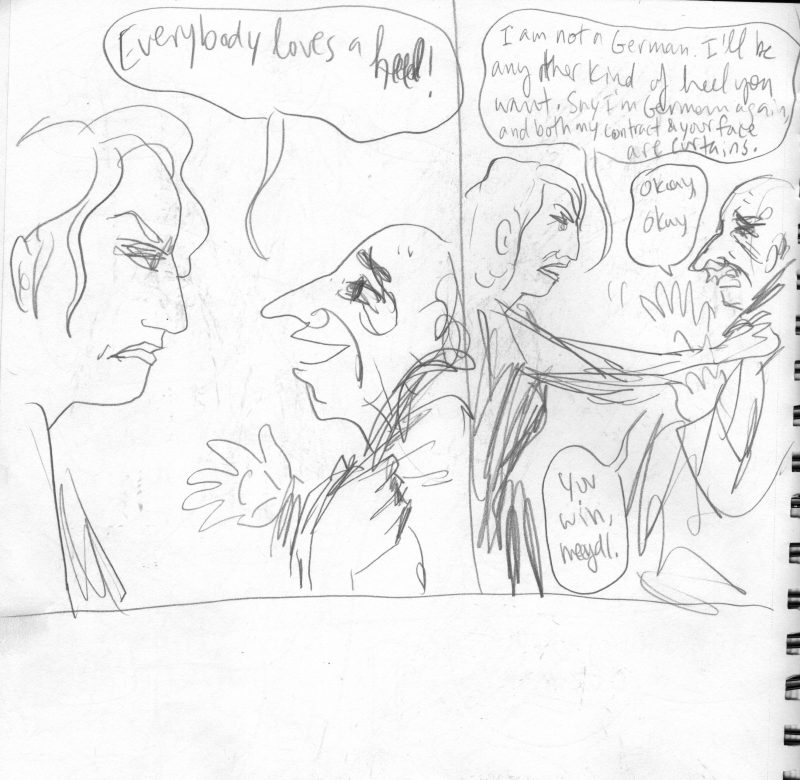

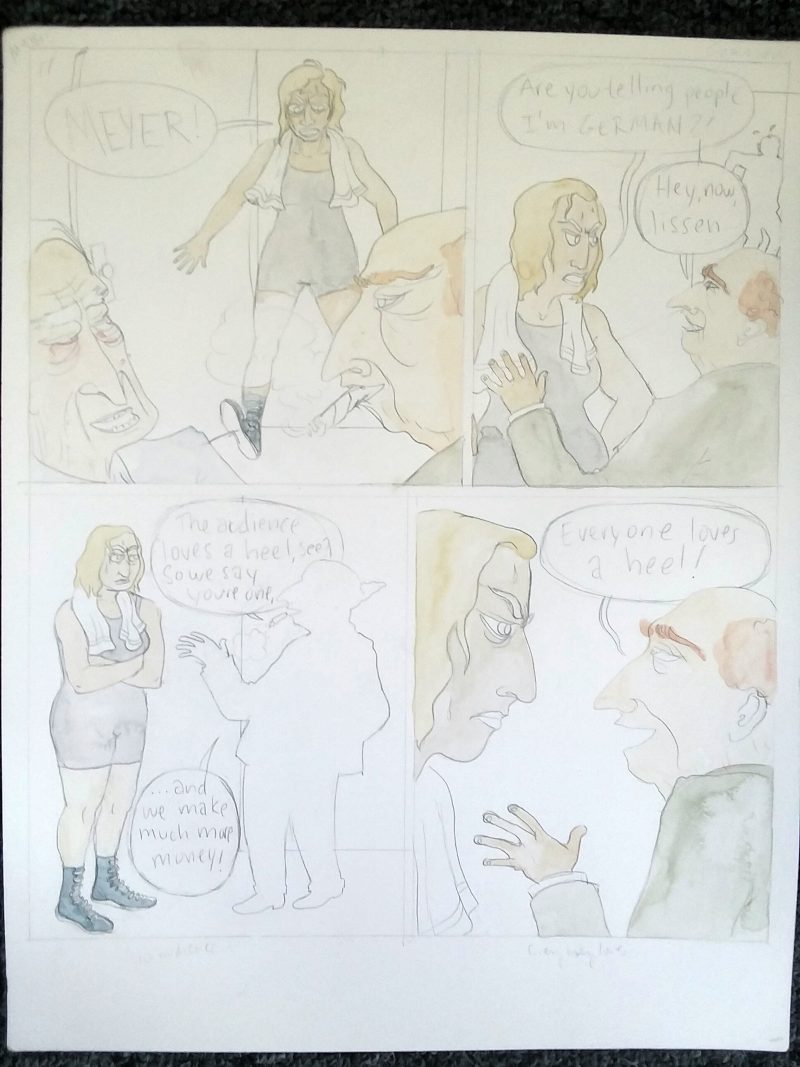

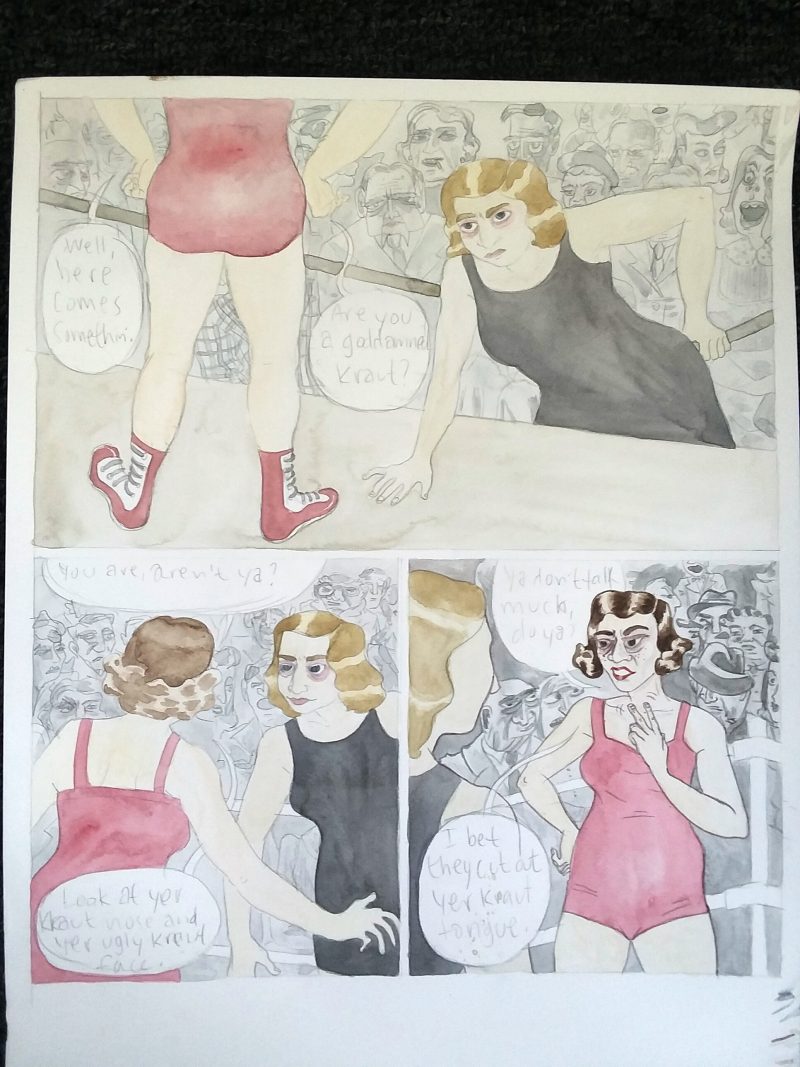

LEELA CORMAN: Its beginnings were a little nebulous. At some point I began to get interested in images of women working in war industries during WWII, in the US. I started collecting them, and thinking about setting a comic amongst them. This must have been when I was pregnant with my second daughter, because I have a memory of discussing this idea with someone about a week before she was born. The rest kind of snowballed as I put my attention on it. I honestly cannot tell you how my teenaged Jewish refugee character became a wrestler. But once a process like this begins, this is the kind of alchemy that takes place. Characters start appearing, and they tell you who they are. “I’m a refugee with PTSD and I fucking wrestle, draw me.”

BLVR: What’s your process like?

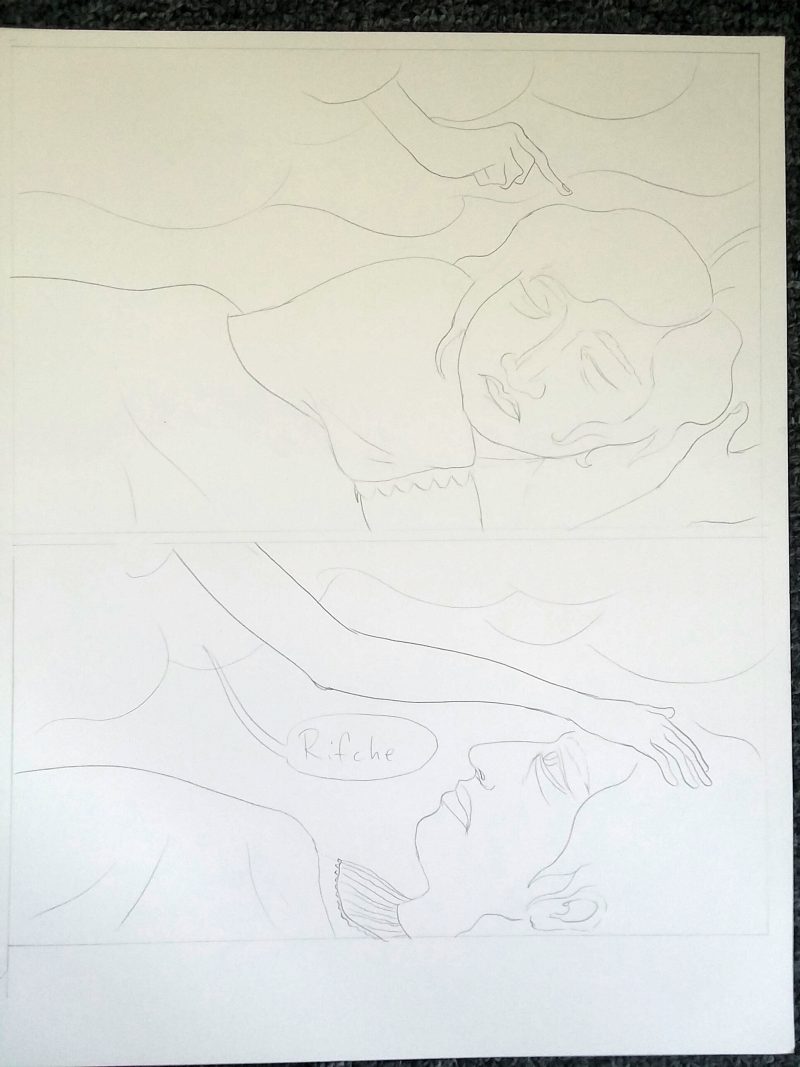

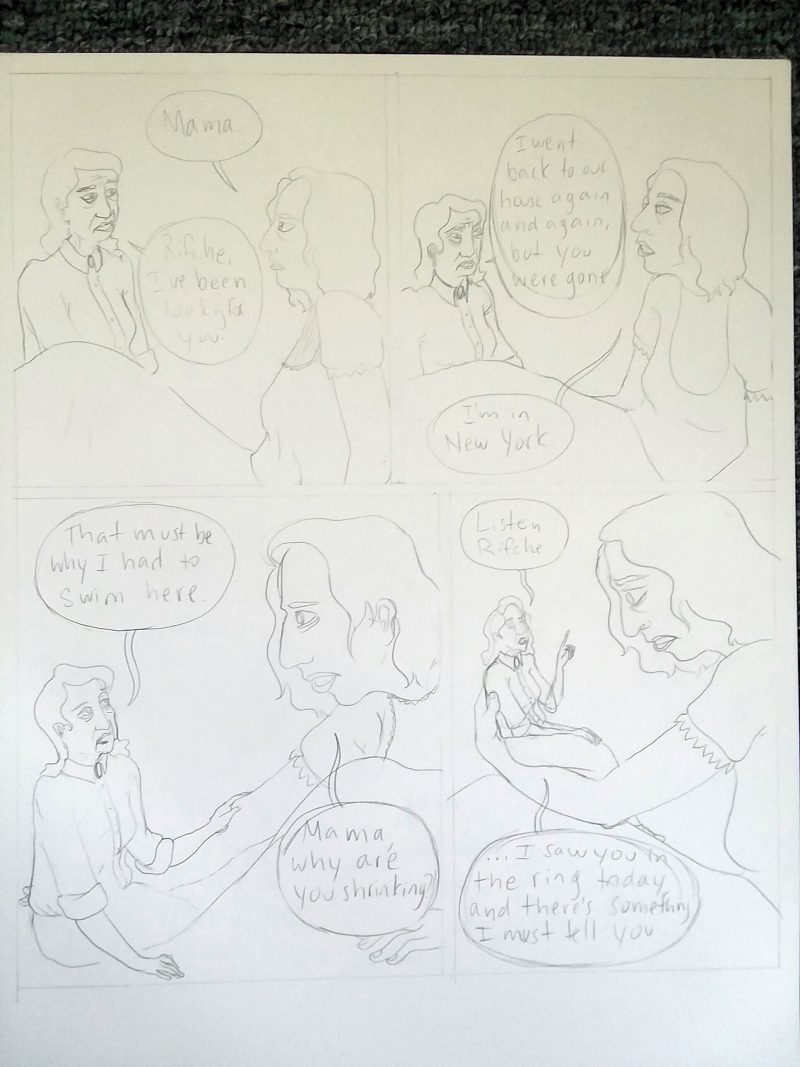

LC: It’s a maddening back and forth between research and writing/thumbnailing. It never stops until the final work is done and delivered. In a novel-length book like this, the process involves a lot of humbling despair about the reality that I will never actually know enough about the time and place I’ve chosen to set the book in. That’s where I am now. I spend a lot of time reading about my topic(s), and while I do that I keep a stack of notecards and a pencil nearby. I write any idea that comes to me in my research on a notecard, one per, whether it’s a plot point, a beat, a statement a character might make, a historical detail I want to include, whatever it is. That way I can take out cards and arrange them to help me generate a part of the story, and also to remind me, like, a year later, of this great thing I read and need to include.

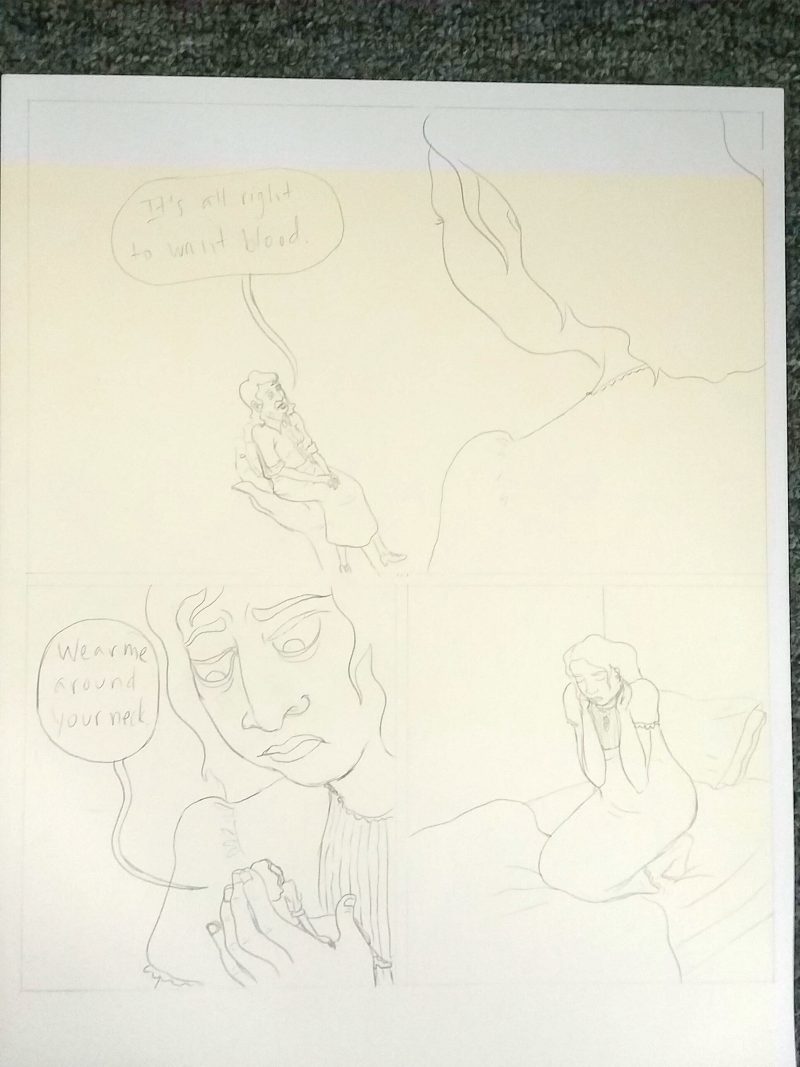

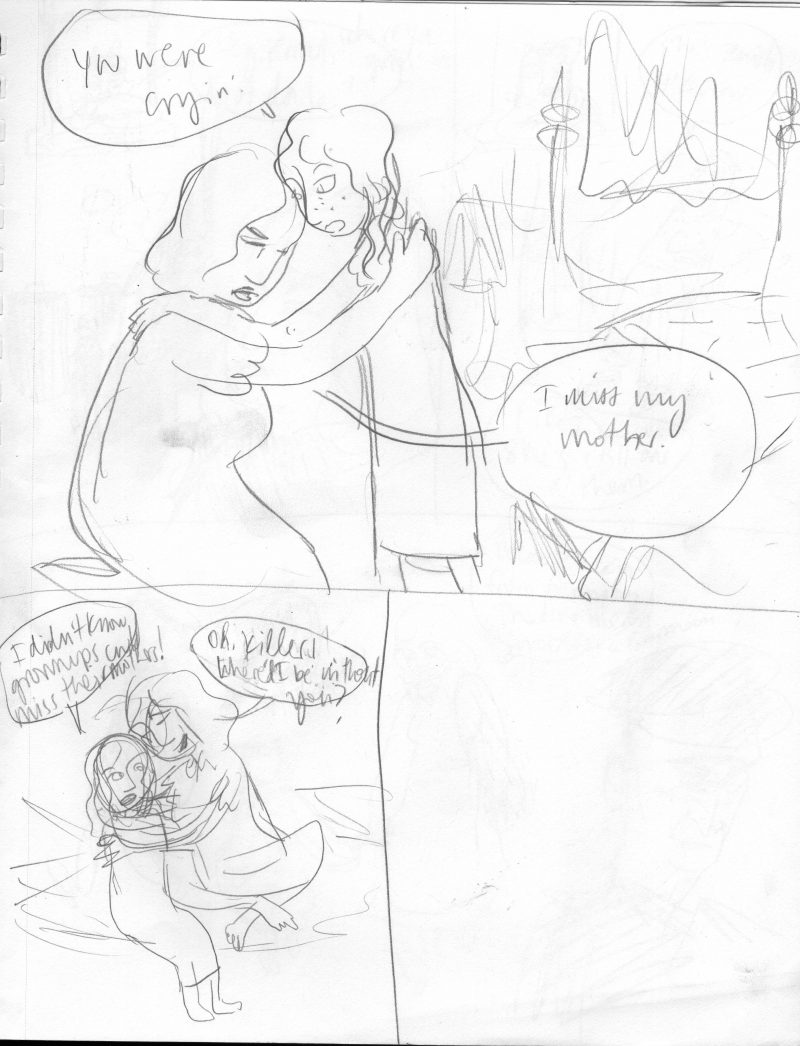

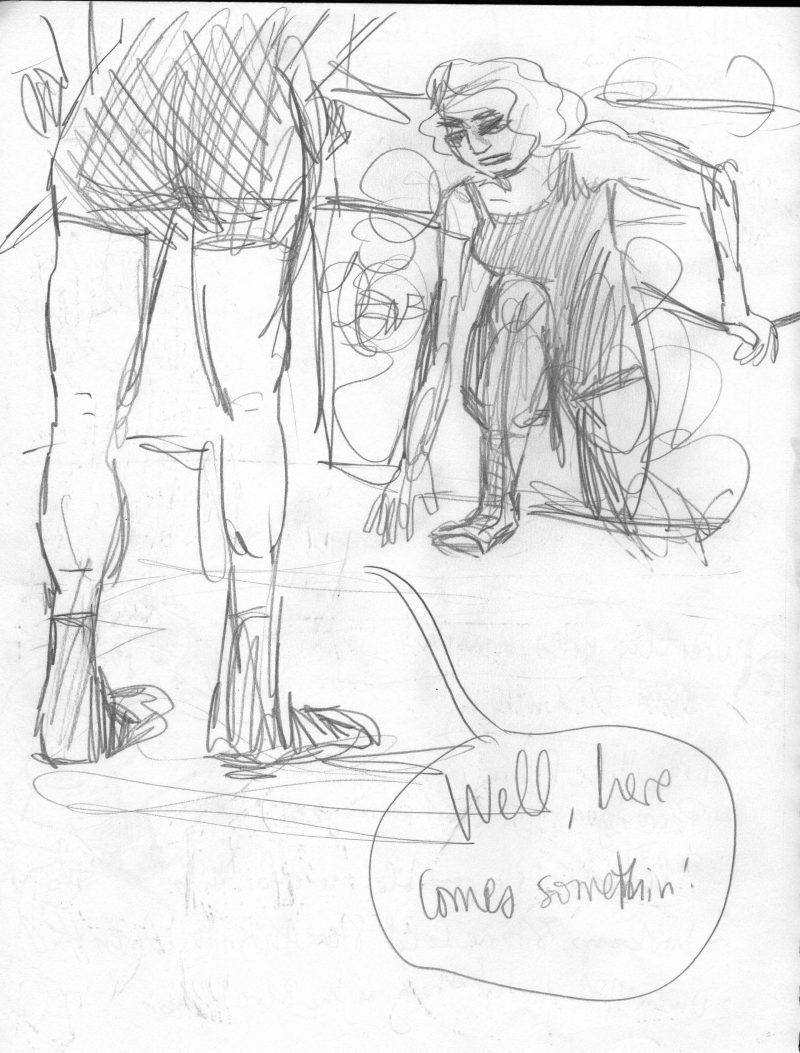

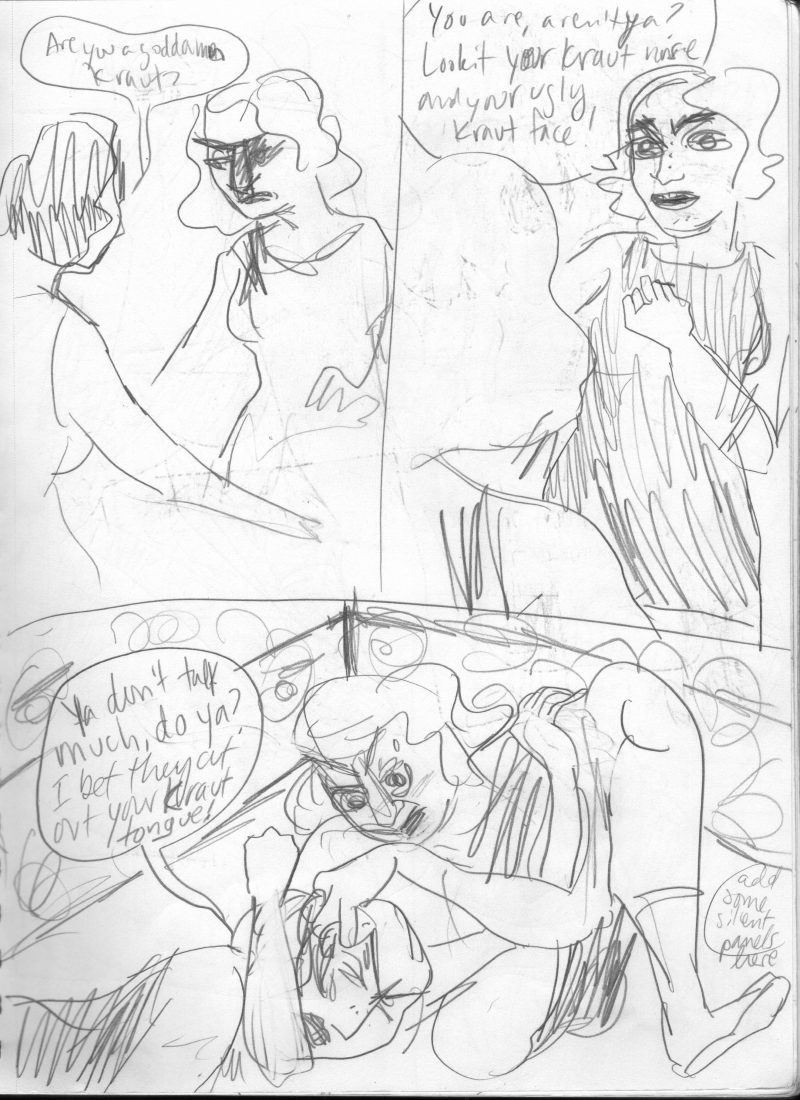

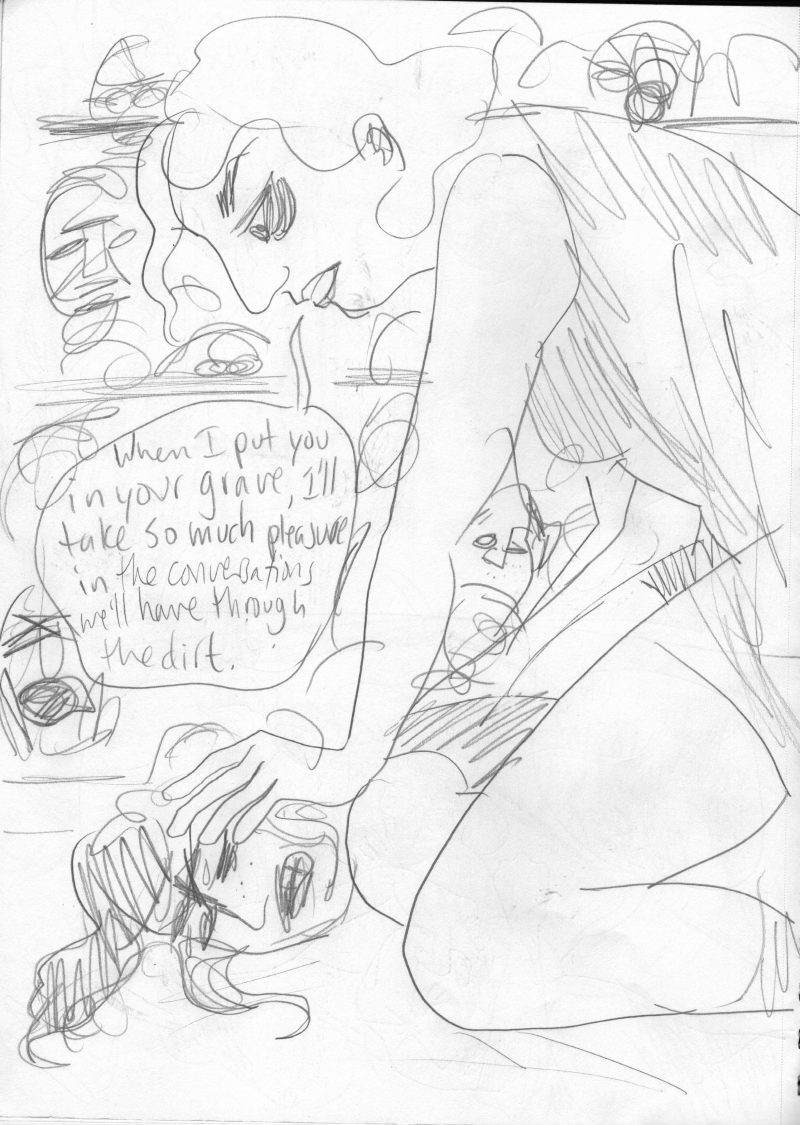

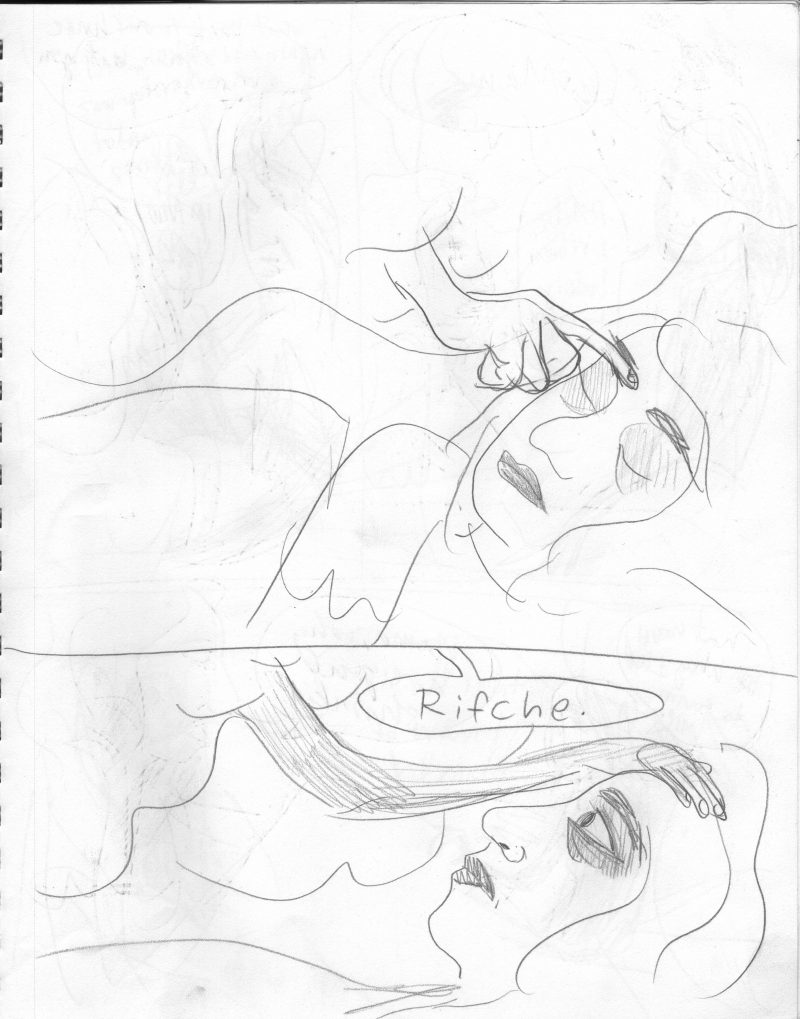

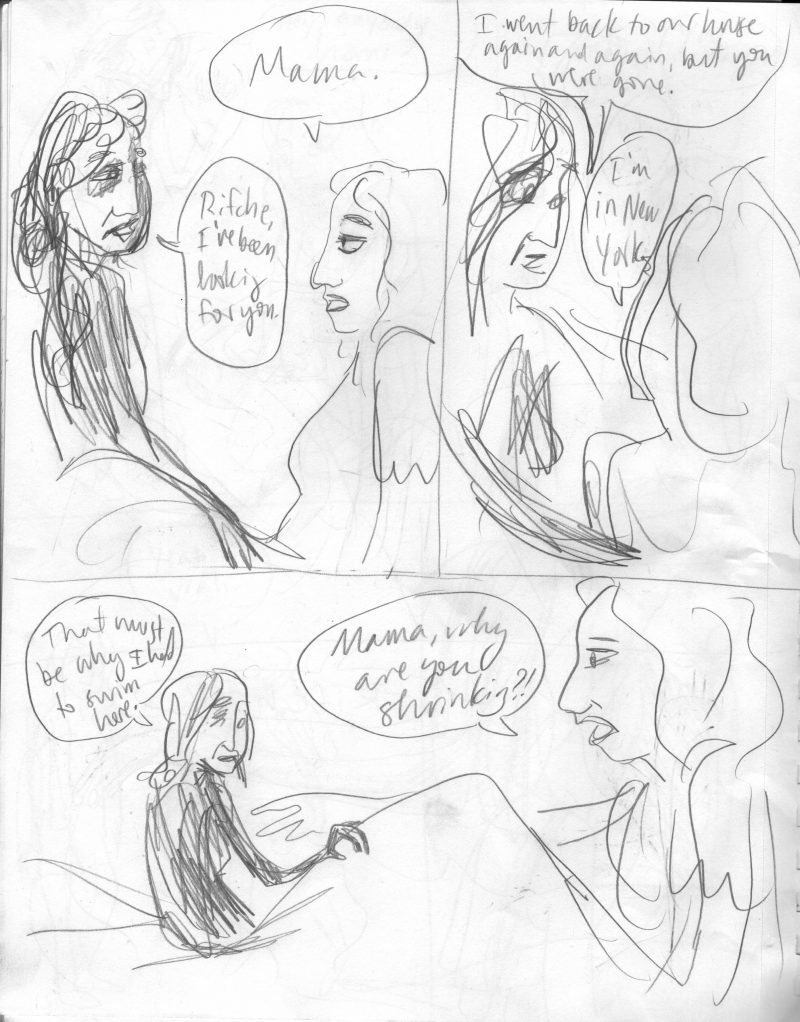

When I’m actually writing, I don’t write a prose script. I thumbnail the story, and that’s where dialogue comes, and often where characters reveal themselves the most. This is where surprise begins to enter. Then there is another aspect of the process: there’s a portal that opens above me, or in me, or I don’t know where, from which emerges the really important parts of both the narrative and the art. That’s where I surrender to larger forces, and play with life and death in my work. That happens more and more often now, and it’s my favorite thing. It’s partially due to my materials, because at the point in the process where I’m working on the final art, I’m using a combination of watercolor and iridescent & metallic liquid inks & acrylics, working with viscosity and tone, and creating the part of the story that is nonverbal and travels within the color and the tonal shifts in the paint, as a secondary signal beneath the straight narrative. That I am not controlling, I am only marshaling it from the portal, through my body, and onto the page. The mystical aspects of the work are contained in the materials themselves, and unlock themselves there.

BLVR: Was any aspect of making this work particularly challenging?

LC: Not so much this excerpt, but overall, this project presents me with a set of ongoing challenges, from the vastness of the subjects I have foolishly decided to write about, to my time management skills, to my shifting ideas & interests within the story. But the greatest challenge is in working with traumatic subject matter. I have a very strong stomach for Holocaust research. I can watch a lot of horrible raw footage of lagers, before the film was edited into something deemed palatable for the public. I can look at those shots panning through the rooms full of dissected humans in jars, the piles of emaciated bodies bleeding into the mud, the lingering closeups on the faces of captured SS guards. I can read one account after another of vets who stumbled on those places as they talk about it, often for the first time in forty years. But it takes a delayed toll on me that I only see later, when I get home to my family. It sometimes takes a toll on them. Other than that, it’s the natural amount of time that it can take for ideas to gestate, which does not happen within the same time frame as deadlines.

BLVR: What drives you to create new work?

LC: There is nothing else that drives me. I’m like an animal designed for a set of specific tasks and behaviors. I can’t imagine being me without doing this, I would die. It would be the end of my physical ability to live. But it wouldn’t happen, because this is the kind of animal I am, and it can’t be changed anymore than a sloth could become a cheetah. If it ever does happen, book the cremation services because I’m not long for this world.

BLVR: Without naming any comics artists, what influences you most?

LC: Can I name artists in other disciplines? The German painters of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, especially Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Jeanne Mammen, but they’re not the only ones. Northern Renaissance portraits. Islamic miniatures, especially Persian and Ottoman ones. The feeling of standing in front of a Rothko. Any painter of the human figure who is uncompromising in their eye, like Lucian Freud. The films of Fatih Akin and Pedro Almodovar. The music and intellectual sensibilities of Blixa Bargeld, and Einsturzende Neubauten in general, and Neko Case’s songwriting—if I could make a comic half as powerful as her “Fox Confessor Brings The Flood” or EN’s “Lament”, I’d die happy (I know they’re albums and not comics, but music is the highest, no?). Intense heavy emotional noise rock. My absolute convictions about putting my art to the cause of showing people the results of Fascism. My love and grief for the lost scrappy tough Yiddish culture of Europe and NYC before the war. My family’s particular Holocaust story, which didn’t involve camps at all, and was equally horrific. My own personal losses, which kept me with one foot on the other side for five years. The experience of being a woman, dealing on a regular basis with blood and viscera, and in my particular case having given birth and having held the corpse of my first child, standing at the gates of life and death and wondering why the world can’t see that that is where women live, my fury at that denial of our power and my desire to pour blood over it. The fact that though I wish it weren’t so, I know how to mix the color of a corpse without thinking about it, because no matter how traumatized you are, if you had that Bauhaus-based color theory education, those skills never leave you. My childhood in New York, a New York that’s gone now but it’s in me and in all of us who were raised there. My love of bodies in motion and of physical movement in general, my love of cities.

BLVR: Which comic should we drop everything and read right now?

LC: Emil Ferris’s My Favorite Thing Is Monsters.

BLVR: What are you working on next?

LC: Well, Victory Parade is going to take more time. But after that, I’m not sure. There are some illustration projects waiting their turn with me. As far as comics, I’m considering another longish fictional one set in the NYC of my childhood and adolescence, about growing up in the late Cold War era, being terrified of nuclear war, all the shit anyone raised in the 80s remembers, but specific to NYC, so there’ll be a lot of art, music and city stuff in there. But I’m really not sure yet. I’ll probably need a breather after I finish VP, like, a couple of months of pedicures and spending time in nature. I think the first thing I’m going to work on when it’s done is getting myself into the ocean for a cleansing beating in the surf.