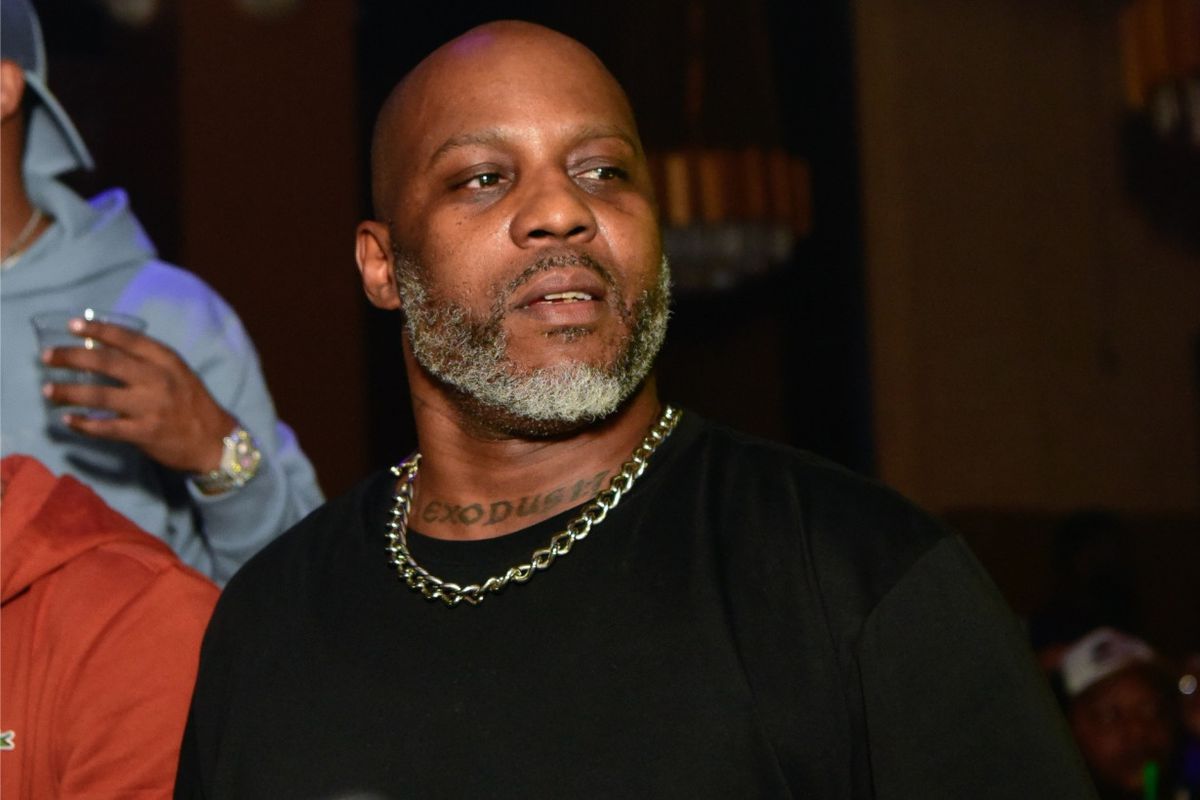

Someone who knew what he was talking about once told me you can find out all you need to know about a rapper from the first line of the first single off their first album. While others spit that Wonderama shit me and my conglomerates shall remain anonymous, caught up in the finest shit. Hi kids, do you like violence? Wanna see me stick nine-inch nails through each one of my eyelids? From the depths of the sea, back to the block, Snoop Doggy Dogg funky as the-the-the DOC. Jay’s the smooth crimes guy, Em’s a self-aware pop-culture pustule, Snoop’s the dude who can say any old shit and make it sound cool. Here’s DMX’s: What must I go through to show you shit is real?

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in