I’m old enough to have experienced the deaths of some musical heroes, like George Harrison, or more recently, Prince. Yet none hit me as hard as the news that Greg “Shock-G” Jacobs, leader of the hip-hop crew Digital Underground, was found dead in a Tampa hotel room on April 22, 2021. I got to know Shock over the past two decades, and seeing a raft of notices of his death feels vastly different than it did for any of these other idols.

If it seems ridiculous to put the creator of “The Humpty Dance” in the same pantheon as Prince or a Beatle, trust me, I’ve been hearing that since 1990, but my opinion has never wavered. I started listening to hip-hop during its late-’80s-to-mid-’90s Golden Age, and, though seldom described as such, Digital Underground is as significant a crew as Public Enemy, De La Soul, or N.W.A. The epoch-making success of Dr. Dre’s move from his uptempo N.W.A production style to the slow grooves of G-Funk on The Chronic (1992) has obscured Shock’s crucial role in the development of West Coast rap, for he was the first to bring the George Clinton/P-Funk sound into hip-hop production on DU’s earliest discs, Sex Packets (1990), This Is an EP Release (1991), and Sons of the P (1991), the latter of which features an appearance by Clinton himself. Clinton was at the nadir of his career before Shock brought him back into popular consciousness.

Yet Shock was unfailingly modest whenever I insisted on this. “I think we definitely leaned on George a little more than most groups back then,” he allowed, the first time I interviewed him, “but it was right around that time when it was in the air; it was next anyway.” Maybe. But Shock’s other innovation was to combine Clinton-style funk with a maximalist production sensibility that owed more to Sign O’ the Times-era Prince, doubling or tripling parts, building up and breaking down thick layers of sound. Zoom into the album version of “The Humpty Dance” around 5:05, where the beat splits into its separate components, alternating between a tambourine pulse with a snare and a closed hi-hat with a clap, before reassembling into the combination that drives most of the song. Listening to DU through headphones taught me a lot about how hip-hop was made, even as I felt no other rap producer before the ProTools era, not even Dre, provided the depth of layers and attention to detail that Shock did.

As a pop star, however, Shock did everything wrong. He was always producing under pseudonyms, like “The D-Flow Production Squad,” out of generosity to various co-contributors, but as a result, most listeners pre-internet didn’t know he produced 2pac’s breakout single “I Get Around.” Producing a monster hit helps your career much less if no one knows you did it. And while Shock continually brought new rappers into his group—besides discovering and debuting 2pac, he boosted the careers of artists like the Luniz, Saafir, and Mystic—he playfully disguised how much of DU was just him. DU’s visual artist Rackadelic, the Piano Man, and most famously Humpty Hump, all of these were Shock himself. (I genuinely thought Humpty was a different person until I saw them live for the first time in 1999, though he maintained the ruse with decreasing rigor over time.) He always cited Clinton as inspiration for making art “in character,” but he was too good at it, blurring his accomplishments and making his post-major-label career needlessly difficult.

But again, Shock was generous. When I met him at a show in 2002, I had little to offer except a fan’s enthusiasm, but he let me hop on the tour bus, go back to the hotel, and interview him between 2 and 5 a.m. He later said it was because he liked my questions; where most interviewers focused on wriggling 2pac anecdotes out of him, I was more a DU superfan, asking about the unknown contributors, like Big Money Odis. And face it, there weren’t tons of writers bothering him around this time. The last real DU album, Who Got the Gravy? (1998), failed to yield a hit, and the group was strictly a touring entity afterward, on the road 200 or more days a year, though he was building up to his 2004 solo album, Fear of a Mixed Planet, self-financed, as all labels wanted to discuss was a new Humpty Hump hit. Fear is a masterpiece, but it was expensive and time-consuming, as Shock resisted the desktop revolution and insisted on recording in traditional studios. I know this was a source of frustration to some DU members, because if he’d been willing forgo studios, he could’ve made way more music. But he could hear the difference and was almost painfully sensitive to recording quality. The studio was his line in the sand, and it was hard to get serious recording out of him without one.

By the time of his solo album, I was publishing articles on rap, often relying on connections made backstage at DU shows, so I was able to write about Fear, which was critically well received but commercially unsuccessful. We stayed in touch, and I found ways to keep writing about him, previewing his stage show, for example, for the San Francisco Bay Guardian when DU came to town, because even throughout these label-less, recordless years, Shock always put on a show, running proceedings from behind his keyboard, incorporating props and costumes, sometimes handing out liquor from the stage. They were like no other hip-hop shows I’ve seen and owed much to his P-Funk obsession. DU had enough hits to make it work, and Shock incorporated affiliated songs like “I Get Around” and the Luniz’s “I Got 5 on It” and even jammed on covers like Dre’s “Xxplosive” over which the crew would freestyle. They were joyous, chaotic affairs but Shock imposed a musicianship not usually seen at a club-level rap show.

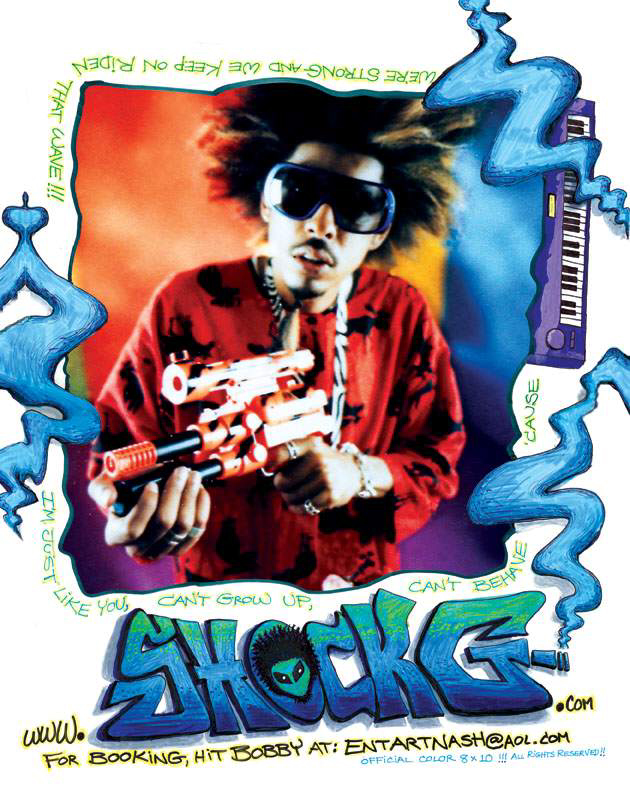

My friendship with Shock was professional, but occasionally more personal. We mostly communicated when I was writing on him, but sometimes checked in at random. I picked him up from the airport once, and once he ended up over my apartment in Oakland. He once persuaded me to put a secret message for a girlfriend in one of our articles, and I once came up with an idea for a DU song, a story I’ve told elsewhere. Mostly I got to observe him backstage before shows or in hotels afterward. He was an old school bandleader, marshalling an anarchic crew to put on a show night after night; I saw him chew people out or peptalk them up. I once saw him threaten to punch someone in the face. But such moments were rare. Shock mostly seemed to govern by exuding an unflappable cool, assuming a level of decorum that was not to be violated. He tolerated outlandish behavior by the crew, but you had to show up and hit your marks at showtime, or you were gone. He took performing seriously, and one of the main reasons he broke up DU in 2008 was because he thought the crew no longer did. “The energy was gettin’ bad,” he said in an article I wrote announcing the group’s demise, though it took another two years to wrap up engagements. There was a plan to reform DU in ten years, though Shock found ways to push it back, claiming other members violated their accord, and in truth I don’t think he wanted to reunite. He was happier doing solo shows or what he called the Shock-G3 Trio, a band featuring former DU members PeeWee on guitar and DJ Fuze jamming on his catalog or whatever else he felt like playing.

It seems funny to suggest the creator of so indelible a comedic character as Humpty Hump was a tortured artistic genius but he was. Humpty was part of the problem. Shock never grew to hate Humpty, because he really was Humpty; Humpty very much embodied Greg Jacobs’ goofy, raunchy, cornball sense of humor in contrast to the low-key, smooth charisma of Shock-G. But he was frustrated by the fact that he was more popular as Humpty than Shock. He had art to make that had nothing to do with a plastic nose, and the wonder is he didn’t immediately cut a Humpty solo album on the back of the platinum success of “The Humpty Dance.” He had too much artistic integrity. Yet he still suffered the routine dismissal of DU as a novelty act, despite the fact that “The Humpty Dance” is one of the most sampled hip-hop songs of all time. That’s not a novelty, that’s inaugurating a discourse. What he contributed to the development of hip-hop production is of far greater impact and import than the character of Humpty Hump, but he seldom got the credit he deserved.

I don’t claim to know anything about Shock’s death, but I’m not going to lie: he was in a bad place over the last year. He’d fled L.A. for Tampa a few years ago to escape his drug connections, but it didn’t help, and he’d been in rehab at least twice since. He definitely fell off the wagon when the pandemic hit. Like many rappers, Shock was an issuer of proclamations, via text, email, or his preferred medium, video message, to what amounted to a private social media circle of his friends and family. Many of the ones I received over the past year were frankly disturbing. Shock was a seeker of knowledge and he had a science-fiction-style imagination that flourished in DU’s afro-futurist aesthetics. But this predilection also made him vulnerable to conspiracy theories, and he was spinning into paranoia about things like nanobots invading his hotel room through the tap water or the fictional Israeli COVID-19 prevention through lemon juice. It wasn’t QAnon but it was just as divorced from reality. I’m sure the forced hiatus from performing and traveling didn’t help. It hurt to see him this way. Shock brought me so much joy with his art, and I count getting to know one of my musical heroes as among the greatest things to happen to me as a writer. I’d much rather remember the effortlessly cool musician with his endless eye for sartorial flair, the man of cosmic and ecological consciousness, the interrogator of false racial divisions and human nutrition that was Shock-G. The man I saw kill an hour after a free summer show in an Oakland ghetto signing autographs for excited kids too young to even know who he was. Or the man I saw backstage at the Red Devil, at an upright piano, eyes closed, playing Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” as he steeled himself for the upcoming show. I’d rather remember the genius I knew.