Still from WALL-E, dir: Andrew Stanton, 2008.

Still from WALL-E, dir: Andrew Stanton, 2008.

The future of contemporary art resides in waste, in the repulsive remainders of totalitarian capitalism stored in warehouses, abandoned housing blocks, and the sort of places that the robot in the film WALL-E had devoted his life to cleaning. This is what Nicolas Bourriaud argues in The Exform, his new book published in London as part of the Verso Futures series.

The Exform is a curious mixture of art theory, structuralism, and pop culture references. Bourriaud, a former curator at Tate Britain and director of the National School of Fine Arts in Paris, is best known for Relational Aesthetics, a book that takes its title from a 1995 article where he identified contemporary art’s focus on how things relate to consciousness. The article emphasized the relationship between art and its audience, and it is precisely from this notion of relational aesthetics that Bourriaud’s new concept, the “exform”, takes root. The exform, like relational aesthetics, exists in a site “where border negotiations unfold between what is rejected and what is admitted, products and waste.” Bourriaud defines exform as a “point of contact,” “a plug”, a “socket” and a sign “that switches between centre and periphery, floating between dissidence and power.”

What to do with waste in this overfull world is the main question in Bourriaud’s somewhat vaguely written book. He is the first to confess that he had begun writing with a vague idea, which he confronted with clear images (Bourriaud’s methodology in putting this book together comes from a Maoist slogan in Jean-Luc Godard’s film La Chinoise). The idea of the book is to resist the temptation to deduce a theory about contemporary art after giving an account of recent works; Bourriaud wants to take the opposite course, with not completely satisfying results.

On the face of it, The Exform is a love letter to French philosopher Louis Althusser whose obsession with deconstructing the inner mechanisms of the notion of ideology Bourriaud seeks to apply to artworks. The book reads like an exercise in imagining Althusser as an art critic. In On Ideology Althusser had shown how ideology has to be repeated on a daily basis by the ideological instruments of the state in order to survive—it is a mechanism, he argued, that can exist only through repetition critical theory has to reveal. This is philosophical realism dismantling the idealism of ideology; a similar approach is needed in art criticism, according to Bourriaud and this can be achieved by revealing the linkage points of our overfull world where we live “in archives ready to burst, among more and more perishable products, junk food and bottlenecks.”

Bourriaud picks an interesting starting point, and takes us back some 37 years, to March 15, 1980. On that day, at the École Freudienne de Paris in the fifteenth arrondissement of Paris, the elderly French philosopher Jacques Lacan had been lecturing to a crowd in a low voice when Althusser entered the lecture hall in a state of agitation. After listening to Lacan for a while, the frustrated Marxist took the floor:

Seizing the microphone, the philosopher calls those in attendance fearful and cowardly, strangely comparing them to “a woman attempting to sift our lentils while war is breaking out.” He declares that he is speaking “on behalf of … the worldwide crowd of analysands, millions of men, women, and children’, in order that “their existence and … problems and the risks they run when they enter into analysis be taken seriously.” “That’s it, that just it,” Lacan is supposed to have agreed…

Althusser, who would go on to throttle and kill his partner Helene Rytman six months later, was taking a stand on behalf of the proletariat, the analysands who had been subjected to the ideology of psychoanalysis in a process that ultimately made capitalist individuals out of them; they were the wretched of the earth. Althusser’s later branding as a psychotic and apparatchik of the French Communist Party would turn him into an embarrassing figure, Bourriaud reminds us, and this needs fixing. Why? Because his critique is necessary and applies to the proletariat of our own day: the waste itself, which the dictionary defines as “what is cast off when something is made.”

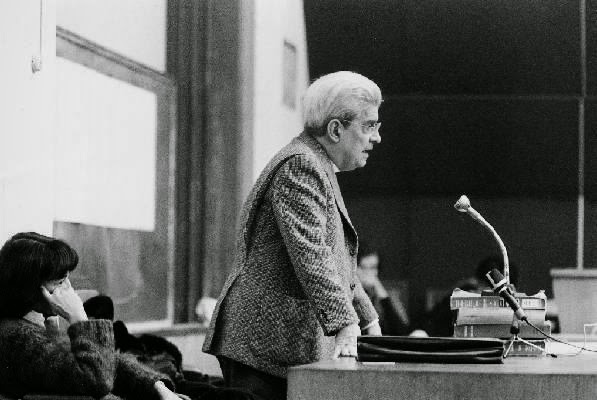

Jacques Lacan lecturing at the École Freudienne de Paris, 1973. CC

Jacques Lacan lecturing at the École Freudienne de Paris, 1973. CC

Waste, like the proletariat of the nineteenth century, needs attention. Once applied only to abandoned workers, the proletariat’s meaning now also includes of “all who have been stripped of experience… and forced to replace being with having in their everyday lives.” Waste piles up in what Bourriaud describes as an “devalued ensemble of what one cannot bear to see” and realism demands us to reveal exactly that. The post-structuralist philosophers (Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari) Bourriaud’s generation has favored over old school Marxists like Althusser, made them lose sight of the process of political liquidation taking place, leading to “progressive amnesia, resignation and powerlessness”. Bourriaud wants us to transfer Althusser’s old school, Marxist defense of the analysand, the downtrodden, the proletariat, to contemporary art and apply it to the excluded and the expunged.

The idea of centralizing waste has socialist roots: by “capitalizing on what capital has repressed”, Bourriaud restructures waste as a source of energy. This source of energy reveals itself throughout the book in parallel with Butler and Athanasiou’s ideas on dispossession. As something in between center and periphery, official and rejected, dominant and dominated, dissidence and power, excluded and included, exform underlies many present-day theories and art that is produced around them. What is left behind, in reality, is the artists’s dream of making art an activity without waste. Their dream is to create art that is always useful or significant.

Waste is definitely a source of energy for many contemporary artists due to the ever-changing nature of different media. This junk culture tends to reveal itself on all artistic and cultural levels. Bourriaud presents some examples of contemporary art in the text, which bring to mind other artists who also deal with the notion of exform in their work.

In her short text titled Ugly Bits the artist Katherine Behar asks: “as we code ourselves into technology, bit for bit, what becomes of the ugly bits?” Perhaps the ugly bits are now essential parts of the conversation. Behar’s artistic practice also focuses on the exform: her installation E-Waste (2014) is a timeless dystopia; handmade bits and pieces of machine-made electronic sculptures in the installation are both futuristic and aged, analog and digital, animate and inanimate.

Re-circulating digital material in her works, internet artist and theorist Olia Lialina uses digital junk to create inbetween narratives. She uses a language that is both visual and textual, and digital. Her stories are both narrated and interactive. The artist Brad Troemel is similarly interested the digital forms of exform; he explores the points of contacts between producer and user, real and virtual, and significant and trivial in his works. He also talks about some digital examples of Relational Aesthetics in his essay titled “What Relational Aesthetics Can Learn From 4Chan?” which tie into the idea of exform practiced in a collective way.

Gustave Courbet, The Stonebreakers , 1849, oil on canvas. 165×257 cm. CC

Gustave Courbet, The Stonebreakers , 1849, oil on canvas. 165×257 cm. CC

Throughout The Exform, Bourriaud elaborates on different approaches to reality and discusses the idea of exform in terms of what reality means in today’s accelerated context. In his discussions of reality, he quotes Althusser again: “the reality has no double: everything is right there before our eyes.” However, this idea is not developed but abandoned quickly when he states “to be able to act, one must view the real as a void.” If the real is a void, “a dead zone”, perhaps the real bits are the ugly bits.

Bourriaud goes on to write about time moving in different directions and producing different realities: “All works of art modifies past and future alike,” he writes. This idea of different paces of change in art is explained under the section “heterochronies”. Perhaps one of the most interesting passages of the book is in this chapter where he elaborates on artistic forms that stand outside of time.

What are contemporary shapes, and how do we visualize “today”? Bourriaud’s answer to these questions is accurate, relevant and telling:

The horizon of the present, both conceptually and visually, seems to be dominated by pulverization, scattering and links. Clusters, clouds, tree structures, constellations, webs, archipelagos. . . All these forms evoke pixels—as if to signal the decomposable structure of the universe and the precarious nature of our political systems.

The forms Bourriaud discusses here bring to mind Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the rhizome. The decomposable structures connect to each other in systematic ways; there can be connections between all levels. Perhaps we visualize today similarly, as a connected and retrievable being.

Toward the end of the text, Bourriaud goes into talking about realism and contemporary art. In his words “Reality is always a product of consensus, and art is a break in this consensus.”

He draws a parallel between Courbet’s realism and contemporary art practice, and reminds us Courbet’s words: “Historical art is by nature contemporary.” Courbet’s realism is an idealization, a criticism of cultural hierarchies where he redistributes values. According to Courbet, every artist had to represent his or her own era. This was of course revolutionary in the 19th century, and foreshadowed ways of thinking about the present-day. It is apparent now how far-sighted Courbet was. But how about Bourriaud? Is waste really the future of contemporary art? Will the future prove him right?

Kaya Genç is an essayist from Istanbul.

Ulya Soley is a curator currently based in London.