The scariest hour is the one before you go home. That’s when you find your blue lips, your bleeders. The intercom takes you on a tour of the hospital: “Rapid Response, fifth floor.” “Code Gray, cafeteria.” “Anesthesia, Labor and Delivery.” “Stroke Code, Emergency Room.”

Morning rounds, and everyone’s on edge. A traveling medicine show rolls through the ward, barking out orders. They want breathing trials, sedation vacations. They want us to “flip” the patients who are proned—flip them, like cheeseburgers.

My lady in bed two is finally sleeping, worn down by the BiPAP mask. The residents park their computers and read the numbers I’ve scribbled on the glass in dry-erase marker. Without going into the room, they pull up the woman’s CT scan and study it for clues. Our attending gestures at the screen with her coffee. “Here, we’ve got massive bilateral scarring involving all lobes,” she says. “We used to call that honeycomb lung.”

“She’s buying herself a tube,” one of them mutters.

“You put a breathing tube in her,” I say, louder than I probably should, “and you’re never getting it out.”

Maybe I’ve acquired a meanness about me, an ugliness. Maybe it’s the stripe of white in my hair, making me look like a badger. But they don’t mention the tube again. The caravan rolls along.

Have you heard it? Every night at seven: an orchestra of car horns, cowbells, claps and cheers, pots and pans, and oh dear, someone’s blowing into a saxophone.

Last Sunday, before the clapping started, I shut my windows and let down the drapes. I lit some incense and candles, to simulate the cavernous aura of Mass, and opened my bible to the Gospel of Mark.

It is an unusual gospel. The story is clipped at both ends, like a cannoli—no virgin birth; and, strikingly, no resurrection. Jesus appears, he recruits, he baffles and dazzles. At one point he puts a hex on a fig tree because it isn’t bearing fruit. There’s nothing wrong with the tree—figs are out of season—but Jesus curses it anyway. The tree withers and dies. You expect Jesus to fold this event into some kind of moral lesson, but he never does. “May no one ever eat fruit from you again,” he says, bracingly.

Mostly what Jesus does is heal the sick. They are everywhere. So much suffering. A game could be made of diagnosing these ailments. The man with a “shriveled hand” likely has a Dupuytren’s contracture. A woman shunned for being “subject to bleeding for twelve years” probably has a heavy menstrual flow—or, perhaps, hemorrhoids. The boy who yells expletives and “becomes stiff all over” almost certainly has temporal lobe epilepsy. (“Only prayer can drive this kind out,” says Jesus, laying hands on the boy. Gabapentin would also be effective.) And the man whose skin forms pustules and peels away in rotted clumps: Hansen’s Disease. Treatable with rifampin, which turns the urine a vivid, fiery orange.

The seventy-eight-year-old woman in bed two has been desperately trying to avoid intubation. A BiPAP mask grips her face, pumping oxygen deep into her lungs. She’s not allowed to have anything by mouth, not even ice chips. I suspect that what she really needs is Xanax.

“Doing okay in there?” I say, knuckling the glass. She lifts a mittened hand and waves me in.

Gown up, glove up. A surgical mask over my smelly N95. Face shield, bonnet, booties—and one other thing.

I loosen the rubber seal of her mask, and slip a straw through the breach. Her tongue finds the straw; the water in the cup begins to drain.

“Not too fast,” I tell her.

“Thank you,” she says, suppressing a cough.

The calculus of risk has a mobile axis. A balance must always be struck between the probability of death and the certainty of suffering. I give her another sip. If I have any religion left in me, it tells me the dying must be given water.

My patient’s toe fell off. We had him on his side, pressed against the bedrails, and right there, in a twist of linens: a pale white toe. Left foot, middle digit. A crust of blood where it came detached.

I drop the toe into a specimen cup and bring it to the residents. They’ve been hunkering down in the equipment room, these past few weeks, fenced in by bladder scanners and pizza boxes.

I present the toe to the young doctors, who start bouncing theories. Maybe it’s a side effect of the vasopressors, or a sign of hypoxemia. Perhaps it’s related to the clotting issues we’ve been seeing—a cluster of platelets and red blood cells, trapped at the joint, turning the digit necrotic.

Or maybe, I suggest, it’s just one of those weird, inexplicable things that happens from time to time, like spontaneous combustion, or stigmata.

“We’ll bring it up during rounds,” one of them says, and spins around to face his computer.

I feel that something more should be done to ceremonialize the loss of a toe. I doubt the family will want it. In less troubling times, I might wrap the toe in petals from a vase and leave it at the bedside, unexplained, for the next nurse to find. Such pranks seem wildly inappropriate now; and so I drop the toe in a biohazard bin and go to check on my third patient.

The number three must hold some saintly power. It keeps asserting itself. Three gifts, from three kings. Three nights sloshing around in the belly of a great fish. “Before the rooster crows,” Jesus tells a mortified Peter, “you will disown me three times.”

In the Book of Matthew, John the Baptist is dunking sinners in the Jordan River when a young Jesus appears and asks to be baptized. (I always liked John the Baptist, with his sensible diet of locusts and honey.) Jesus scarcely has time to dry off when a seam opens up in the sky. A white dove flies down and perches on Jesus’ shoulder. God looks down . . . and is pleased.

So what does God do? In that moment? How does God demonstrate love to poor Jesus? By torturing him, of course. The white dove leads Jesus into the desert, where he suffers and starves. God sends the devil to tempt Jesus three times: with food, with magic, with “all the kingdoms of the world and their splendor.” With Jesus on the verge of death—likely from some combination of sunstroke, malnutrition, and rhabdomyolysis—angels come and tend to his wounds.

I won’t pretend to understand the symbolic importance of the number three, but I can make a literary argument for God sending Jesus into the desert. The story seems to suggest that the world is an inherently mean and seductive place, driven by a kind of malignant intelligence.

My third patient is bleeding internally. Her hemoglobin keeps dropping; her heart racing to shuttle more blood to her vital organs. I’m on the phone with the blood bank, bargaining for a unit of cells, when a patient down the hall goes into cardiac arrest.

“Soft code,” the charge nurse says, as everyone swarms the room. “Soft code!”

A soft code means we know the patient will die, but we’ve failed to translate this idea from medical jargon into a spiritual vocabulary the family can understand; and so we have to go through the motions of a full code—CPR, epinephrine, electricity—just not get too carried away with it.

I keep an eye on the wall clock as I root through the top drawer of the crash cart. Two minutes. Stop compressions. Check pulse. Resume. I draw up an amp of epi and wonder, as I often do, whether patients would revise their code status if they understood the violence inflicted, the brutality required of us, to feel that thump of blood.

“Can we get the pads on him?” a resident screams, from inside the room.

Just then our attending physician, with her ever-present Dunkin’ cup in hand, saunters onto the unit. “You’re not shocking this patient.” She takes a sip of coffee.

“It’s a wide-complex QRS,” the resident pleads.

“Yes, I can see that.”

Not wanting to risk her changing her mind, I grab the defibrillator—a burdensomely heavy device, with thick wires grouped sloppily into its side pouches—and carry it into the staff bathroom, locking the door behind me.

Truth is, I enjoy doing compressions. There’s romance in CPR: a chance encounter that is tactile, deeply personal; risky and savage and strange. We obliterate the sternum, break all the true ribs. Cherry-red blood fills the stomach and is regurgitated through the mouth and nose. Viral particles pollinate the air.

Defibrillation? Arid. No rubbing of paddles together; no jolting back to life after the jolt—although we do shout: “Clear!” Years ago in a different city, a different epidemic, I watched as an older nurse refused to take her hands off the chest of a teenage overdose, allowing herself to be shocked. I later asked her what it felt like. “A bee sting,” she gruffly stated.

Patients who survive defibrillation—or its sister procedure, cardioversion—describe the effect as being kicked in the chest by a mule. The experience can produce some fascinating insights. Tunnels, yes, and light. A surprising number of people hallucinate babies crawling on the floor. Many describe the scents of coriander, jasmine, and—worrisomely—smoke. A retired astrophysicist who’d collapsed while gardening once told me, “It’s kind of nice, actually. Death.” And one woman with bone cancer, lucid to her last breath, looked me square in the eyes and said, “I’m going back now.” And did.

In the bathroom, coughing. I clean my inhaler with alcohol prep pads and greedily suck its medicine. Hands shaking, I unscrew the cap from a pill bottle and peck around for a Xanax. My face is reddened from the abrasions on my nose and cheeks, and I’m wondering how to get this defibrillator out of here without anyone noticing I took it. And I’m thinking about all the sad ways we’ve laundered our fears with the lingua franca of war. Front lines. Invisible enemy. This is my mask. There are many like it, but this one is mine. We’ve figured out how to moisturize the straps of our N95’s so they don’t burst; how to protect the bony prominences of our faces with Mepilex foam; but none of us, so far as I can tell, has figured out how to sleep.

Twenty minutes left, and my patient with one toe short of a full bouquet starts dropping his pressure. Trying to die on me. This happens often. The critically-ill seem to be able to intuit the chaotic energy of shift change. They can harness that energy and convert it into something useful, soulful—a window of departure.

The intercom, again: “Code Blue, ICU. Code Blue, ICU.”

“Which ICU?” The charge nurse frantically glances around. “Is that us? Is that you?” Her eyes are bloodshot; she seems like she’s ready to cry. “They didn’t say which ICU. They just didn’t say.”

I spike a jar of albumin and hang it high and wide on my troublemaker. I tap the glass, watching the bubbles rise in the inverted jar; the thick, golden medicine creeping through the tubing.

Leaving the room I find the charge nurse slumped at the front desk. “Jesus Christ, I feel like I’m taking crazy pills,” she says, raking her hair with her long fingers. “We can’t admit another patient.”

“I’ll help you,” I say.

But the patient never comes. My relief shows up ten minutes late, a younger nurse who, through some combination of ambition, intelligence, and poor timing, was hired into the ICU straight out of school.

We get along, me and this new nurse. She doesn’t ask a lot of questions during handoff.

“Oh, and he’s missing a toe,” I add to the end of my report.

“We’re amputating toes now?” she says.

“Not exactly.”

I keep my head low as I duck out through a side exit. For weeks security was stopping us as we left the hospital, checking our bags for bleach wipes and toilet rolls. Now they just glumly punch the handicap button, buzzing us out. Nothing worth stealing.

I try not to look at the freezer truck. An aluminum tube connects the truck to the building, supported by a slapdash ramp tagged by vandals. The tube pumps nitrogen into the truck from the boiler room below; and the ramp seems too hastily constructed, too flimsy to hold the weight of the dead. Half the block is cordoned off with orange cones. News vans are parked upwind.

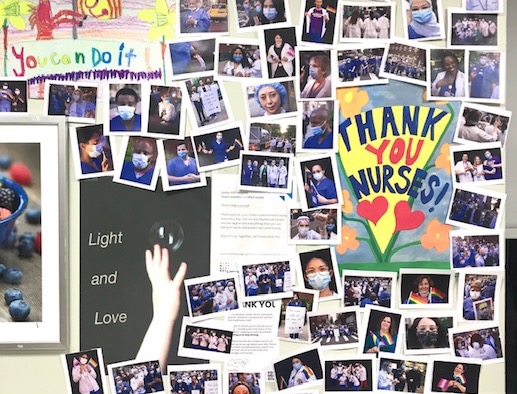

I pull up the wool collar of my jean jacket and stuff my ear buds in, careful not to step on any of the chalk art made by local children. “You are ALL heroes,” one boldly declares. “PEOPLE TAKING CARE OF PEOPLE,” another bluntly observes.

For my walk home I choose an upbeat song, a live version of Bruce Springsteen’s “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City” from London, 1975. What I love about this song is the way it changes, how it travels. One night, back in early March, I went on YouTube and found the concert video. It was their first time playing overseas, and, according to Bruce, he was nervous before the show, during it, and for the next thirty years. You’d never know it. The E. Street Band is dressed to the nines: tailored suits, sharp-collared shirts with open throats, crisp Stetson hats, carnations. Bruce, on the other hand, appears to have wandered onto stage from a nearby Salvation Army. A ludicrously huge wool hat keeps slipping over his scraggly face. It’s unsettling to see this iteration of Bruce—skinny, slithering, possibly high. His beard is that of a very young man, full of gaps and blond wisps; and this is obviously the song of a young man—hammy and overeager, a bit too jazzy for its own good. But then the band does something extraordinary. Silence is weaponized: the lights dim, and, aside from a whisper of piano, a brush of snare drum, all is quiet. The crowd does not clap. A bridge of silence holds them. The drums keep soft time. Bruce moons about the stage, winds the tuning pegs of his Telecaster, ventures over to the guitar section, improvises a three-second solo—a challenge. Steve Van Zandt tries to mirror the solo, doesn’t quite get it. Bruce plays it again. Little Steven finds it, adds a bit extra. Bruce responds, brings more heat. The piano picks up, the bass kicks in, Clarence Clemons bites his mouthpiece, all of them watching Bruce with the same lovingly bedazzled look. Here is a man, says the look, who knows where we’re going.

Halfway home I realize I’m still wearing my N95 mask. I fling the mask into a trash can and take a deep breath. The sun is warm against the cut on the bridge of my nose. Crossing Third Avenue, I step into something smeared and glistening red. A piece of fruit has gone missing from a grocer’s cart, and bees are swarming to it.