This essay is about Edgar Wright’s documentary of the band Sparks. This essay is not about the band Sparks, also known as Ron and Russell Mael, and their brilliant, weird, constantly evolving music. If you set out to watch the film, you likely already knew of Sparks, were already a fan of one or several of their albums, or you saw the trailer knowing nothing of Sparks, and were pulled in by the barrage of talking heads telling you that Sparks is the coolest underground club you have yet to be invited to. Or perhaps you saw a trailer for the film Annette, a forthcoming rock opera film and recent Cannes Film Festival darling written by Sparks and starring Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard. Regardless, by the time you begin The Sparks Brothers, you already know that Sparks is great and that a lot of people already knew that.

Edgar Wright, the director of The Sparks Brothers, also loves Sparks very much. He has used their songs in his vibrant, quirky mainstream films, which include Scott Pilgrim vs The World, Baby Driver, and Hot Fuzz. Wright said in an interview that he wanted to make a film that would give Sparks credit were credit was due, a “long overdue portrait of them as real artists” (nevermind that two biographies have already been published). Because this is the first major piece of media, and likely the last, to involve the “elusive” brothers Mael themselves—both in their seventies—The Sparks Brothers is a once in a lifetime opportunity to make a great documentary about them; to glean as much information as possible about the tight lipped Maels and their mysterious methods and share that with the world. We, the fans, have waited a long time for this, and perhaps that puts undue pressure on Wright. The resulting film clearly tries to please everyone: we do indeed get a trail of biographical crumbs about Sparks and he convincingly argues that they are a band worthy of respect. What it does as a film, and not a report, beyond that is questionable.

The question the film poses: how can a band be unknown and everywhere at the same time? Wright calls Sparks the most “underrated, overlooked, and hugely influential,” a creed echoed by talking heads, including Beck, Jason Schwartzman, Flea, Todd Rundgren, Jane Wiedlin, Patton Oswalt, Duran Duran, and Jack Antonoff. This grayscale chorus of contradiction repeats itself throughout the entire film, interspersed with bites from the Maels, animations, Sparks’s dazzling music videos, and clips of the supposedly anonymous Sparks playing to massive crowds. Wright has two posits: that Sparks was brilliant for their intentionally polarizing music, for not caring about sales, publicity, or even their audience, and for that they languished in the shadows; and that Sparks was highly influential, changing the course of music forever through their chart topping hits and major media appearances for which they are dearly beloved. Neither Wright nor the Maels ever propose what their bar for real success is, but one has to wonder how high it must be if a band that still plays sold out shows after twenty-five albums and five decades hasn’t yet reached it.

The Maels came of age in mid century Los Angeles, the sunset of Hollywood’s golden age. The peek we get into their personal lives is all about their youth, which aside from the early death of their father, was fairly standard. They played football, took piano lessons, went to the movies, and loved their devoted widowed mother. It was she who drove them to a Beatles concert, events of epic, terrifying proportion and screaming hysterical devotion. Quite an impression of fame for two ambitious young men. The Maels divulge their early musical interests: Little Richard, Elvis, and later Mick Jagger, Robert Daltrey, The Who, and The Kinks (a clue as to why they were repeatedly misidentified as a British band). The next real morsel of personal insight we get is that Russell dated The Go-gos guitarist Wiedlin in the 80s, already public knowledge, and then we jump forward lightspeed another few decades to the present day, to an itinerary of creatures of habit Ron and Russell’s daily routine in Los Angeles, which goes as such: exercise in the morning, then coffee, and then tinkering in Russell’s kitschy home studio.

The Sparks Wright presents us with exists in a hermetic cultural vacuum. Even with the most cursory information about Sparks, it is obvious that the Maels are vastly knowledgeable. They couldn’t have had so varied and virtuosic a career, dabbling in so many genres of music and performance, without it. We get a mere two stories of their musical interests past the age of eighteen: a shard of an anecdote about hearing “I Feel Love” on the radio and then wanting to work with Giorgio Moroder, who then produced their 8th album and titular hit, “No 1. Song in Heaven,” and that they admired the Sex Pistols. We know nothing more about even their positive opinions on their contemporaries. I wonder what they made, for instance, of The Talking Heads, a band similarly weird and arty that occasionally broke through. A heartbreaking story about a failed collaboration with filmmaker Jacques Tati sheds no light on why the Maels were drawn to his films. Much is made of the fact that they love French New Wave film but it is never elaborated upon. One can draw the connection—Sparks and Tati share a love of finely tuned craft and oddball humor—but it is sadly unexplored by the Maels. Through a friend of a friend, I know that Ron is a voracious reader; what a gift it would have been to hear him talk about the literary influences that brought him to the unique crossroads of the deeply wacky and profound.

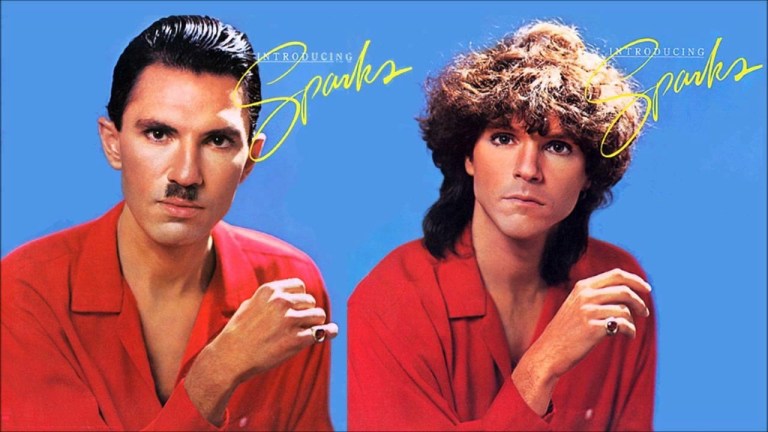

Given Ron and Russell’s allergies to interviews, one can imagine that they agreed to participate with the documentary as long as their lives weren’t pried open, and I suppose kudos to Wright for honoring this hypothetical agreement. The relationship between documentarian and subject is inherently complicated and sensitive. But it is possible, necessary even, to examine the artists projected image. The film just lightly touched upon Ron’s signature moustache, a look that both draws attention to and conceals him through the power of caricature (“one hundred hairs make a man” is the chorus of “Moustache”). In an interview with The Spector, Sparks said, “the vagueness is more interesting than the reality.” Upholding this maxim is what brings a portrait from a Wikipedia page to another art form. It’s why certain biographies stand the test of time. They offer something deeper, more murky: a questioning of persona, money, failure, shame, hunger, exposure, of the necessity of creation itself. They ask awkward questions, something that Wright is seemingly unable to do. We need only to look at documentaries of enigmatic artists such as John Walter’s graceful portrait of Ray Johnson, How to Draw a Bunny and Richard Press’s Bill Cunningham New York to see how successfully one can make the cloak of privacy its own character, while still leaving much to the imagination.

Who we do hear a lot from are fans, including Wright himself. They are famous fans, but they are impassioned fans nonetheless, and offer us no more insight about Sparks than we already have. Over and over we hear: everyone was talking about them, they were brilliant, no one knew them, it was like everything else but better, it was like nothing else at all. Who is served by this? If you are Ron and Russell Mael, I imagine this would be deeply gratifying. You are both recognized for the good work that you’ve done, your successes highlighted, while also vindicated for any felt oversight. If Wright set out to make this film for them alone, while they are still alive, he has done a bang up job. If you are a fan of Sparks, you are given ample proof that you have been right all along, and not only that, you are part of a club of those “in the know,” an exclusive crowd that really knows the good stuff, the obscure stuff.

To answer simply the question that is the heart of the film: it is not possible to be unknown and everywhere at the same time. What the film inadvertently proves is that there is room for art that both strives for integrity and mass appeal. There is a wide tier of fame that is above unknown and below mega-stardom, a perfectly fine place to be. There is no injustice in passing over footholds to fame to sustain independence. But it is not very sexy to say, here is this band that is semi-popular, certainly not as sexy as saying let me turn you onto this cult band.

The Sparks Brothers is ultimately not really about the Sparks brothers but about being a fan of the Sparks brothers. It’s about being in on the joke. The most astute comment in the whole movie is by Flea, who criticizes the general public for their inability to take humor seriously. At the end of the trailer Wright asks them, “why didn’t you participate in a documentary until now?” Ron responds, “we didn’t want to do the standard documentary full of talking heads,” to which Russell adds, “it would become too dry,” before they get doused in the face with a bucket of water. It so perfectly encapsulates their charming and self-effacing sense of humor. Ron’s lyrics are called codes to crack, as if he was a sphinx giving riddles which only the chosen are able to answer, as if his songs weren’t about masturbation and loneliness. They are funny, but they are also deep, and like all good jokes they take a second to sink in. But Sparks doesn’t require deep scrutiny to be able to enjoy. They make, after all, pop music.

Ron and Russell Mael believed in a better world. It’s noble to believe that pop music can be fun but challenging, because it comes from the belief that all people have the capacity for creativity and exploration. It is inherent in everyone, and takes no special gift of heart or mind. To hold this faith in humanity, and enact it in your art, takes bravery; you risk being misunderstood. Could Sparks have been more popular? Sure. They could have had a #1 single on every album, they could have gone platinum, they could have been miserable. As Ron himself says, “who wants to be really popular?”

When I saw Sparks in concert in 2013, I knew little about them aside from having heard and dug their biggest hits. They were on their “Two Hands, One Mouth” tour, which was just Ron on keyboard and Russell on microphone—no other music, no set, just two middle aged men on an otherwise empty stage. Seattle crowds are notoriously stony, but that night the packed floor danced and cheered. Electricity poured from the music; I don’t know how to describe it other than pure magic. Toward the end of the night they played “My Baby’s Taking Me Home.” The first lyric is “my baby’s taking me home,” which repeats a second time, and then a third, and then more than a hundred times, a refrain in the style of the poet Robert Lax but in amplified rapture. The line shifts and metamorphoses into many meanings in your mind. One turn irony, one turn sentiment, then lament. The song culminates into a crescendo of intense prismatic emotion, as a commenter said, “I wasn’t the only one with a few tears when they played this song.” By the end, everyone had caught on, hundreds of voices singing back to the stage in joyous union. I don’t know, maybe you just had to be there, or maybe it isn’t your thing. There are recordings on Youtube, you should check them out. There’s no wrong way to listen to Sparks in a dark room.