Each year, the editors of The Believer give out awards to the works of fiction and poetry they found to be the best written and most underappreciated. This year, for the first time, they have added a third award in the category of nonfiction.

Here are the 2018 winners and finalists for each category. The winners will be honored on April 25 in Las Vegas, on the opening night of the Believer Festival.

Fiction Winner

Belly Up

by Rita Bullwinkel

A Strange Object

In the first story of this collection, a woman witnesses a car accident on the freeway, and her life comes apart at the seams. She sees a dead body and starts to lead a double life, and in Bullwinkel’s hands this isn’t a destructive act, but a generative one. The woman becomes more perceptive to the world, in all of its mundane strangeness, and her perceptiveness lasts through the rest of the stories in this collection—stories that aren’t strange just for the sake of being strange; they are almost religiously so. The possession of a body becomes an unanswerable riddle. A snake named Karl twists himself into the shape of a pear, a ghost gets stuffed into a bucket, and girls want to turn into plants that can fertilize themselves. There’s real tenderness, agency, and humanity coursing through these perfect and uncanny, sharp-witted stories.

In the first story of this collection, a woman witnesses a car accident on the freeway, and her life comes apart at the seams. She sees a dead body and starts to lead a double life, and in Bullwinkel’s hands this isn’t a destructive act, but a generative one. The woman becomes more perceptive to the world, in all of its mundane strangeness, and her perceptiveness lasts through the rest of the stories in this collection—stories that aren’t strange just for the sake of being strange; they are almost religiously so. The possession of a body becomes an unanswerable riddle. A snake named Karl twists himself into the shape of a pear, a ghost gets stuffed into a bucket, and girls want to turn into plants that can fertilize themselves. There’s real tenderness, agency, and humanity coursing through these perfect and uncanny, sharp-witted stories.

Fiction Finalists

Tell Them of Battles, Kings, and Elephants

by Mathias Énard

New Directions

“Bridges are beautiful things,” writes Mathias Énard, “so long as they last.” But what about those that don’t? Tell Them of Battles, Kings, and Elephants tracks the real story of Michelangelo, who was invited to Constantinople by sultan Bayezid II in 1506 to design a bridge across the Bosporus. Énard does more than just relate sketchy historical fragments: what’s been lost to history becomes art in his hands, and Michelangelo becomes flesh and blood. Though an earthquake ultimately destroyed the bridge before it was built, its absence is still a reminder that beauty will never last, unless it does.

“Bridges are beautiful things,” writes Mathias Énard, “so long as they last.” But what about those that don’t? Tell Them of Battles, Kings, and Elephants tracks the real story of Michelangelo, who was invited to Constantinople by sultan Bayezid II in 1506 to design a bridge across the Bosporus. Énard does more than just relate sketchy historical fragments: what’s been lost to history becomes art in his hands, and Michelangelo becomes flesh and blood. Though an earthquake ultimately destroyed the bridge before it was built, its absence is still a reminder that beauty will never last, unless it does.

Your Black Friend and Other Strangers

by Ben Passmore

Silver Sprocket

The comics in this candy-colored collection will make you into an anarchist—or at least that is the hope of Ben Passmore. In his introduction, he professes to teach readers “how to be dangerous, how to be a failure, and how to laugh in the face of a world that wants to crush us.” The title comic, for which Passmore received wide acclaim, was self-published after he read Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks and found a language for the dysphoria he felt when surrounded by whiteness. Most of the stories have political subjects: Black Lives Matter, the ACLU, Trump, police violence. But Passmore refuses to play the role of the “outraged black cartoonist”—other stories are about battling punkish landlords and predatory vampires. The universe of the book is Day-Glo weird and strewn with chaos, and anarchy always gets the last word.

The comics in this candy-colored collection will make you into an anarchist—or at least that is the hope of Ben Passmore. In his introduction, he professes to teach readers “how to be dangerous, how to be a failure, and how to laugh in the face of a world that wants to crush us.” The title comic, for which Passmore received wide acclaim, was self-published after he read Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks and found a language for the dysphoria he felt when surrounded by whiteness. Most of the stories have political subjects: Black Lives Matter, the ACLU, Trump, police violence. But Passmore refuses to play the role of the “outraged black cartoonist”—other stories are about battling punkish landlords and predatory vampires. The universe of the book is Day-Glo weird and strewn with chaos, and anarchy always gets the last word.

Riddance; Or: The Sybil Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers & Hearing-Mouth Children

by Shelley Jackson

Black Balloon Publishing

Jackson’s paranormal tome is an eerie Pale Fire—a hermeneutic fiction that is simultaneously presented and analyzed for its reader. The scholarly protagonist compiling the book is an obsessive archivist, making a collage of clippings, photos, charts, schematics, drawings, and all varieties of text. Together, these documents create a haunted history adjacent to our own. Set in the late 1800s—the age of new spiritual movements—the book functions like a textbook for pseudo-academic fields such as necrophysics and the linguistics of the dead. Jackson uses rich, mouth-felt prose to reimagine words as organic entities, the human throat as a portal to the afterlife, and stuttering as a supernatural gift. This is a singular work, a vast, idiosyncratic study by a writer who continues to experiment with every possible parameter of fiction.

Jackson’s paranormal tome is an eerie Pale Fire—a hermeneutic fiction that is simultaneously presented and analyzed for its reader. The scholarly protagonist compiling the book is an obsessive archivist, making a collage of clippings, photos, charts, schematics, drawings, and all varieties of text. Together, these documents create a haunted history adjacent to our own. Set in the late 1800s—the age of new spiritual movements—the book functions like a textbook for pseudo-academic fields such as necrophysics and the linguistics of the dead. Jackson uses rich, mouth-felt prose to reimagine words as organic entities, the human throat as a portal to the afterlife, and stuttering as a supernatural gift. This is a singular work, a vast, idiosyncratic study by a writer who continues to experiment with every possible parameter of fiction.

Seventeen

by Hideo Yokoyama, translated by Louise Heal Kawai

MCD Books

This book—Yokoyama’s second to appear in English—is an engrossing workplace drama about the Japanese newsroom. Drawn from his experience as a beat reporter, the novel centers on a real-life tragedy—the 1985 crash of a passenger plane—and follows the ethical dilemmas and personality conflicts that arise for the newspaper staffers tasked with deciding which stories to tell, in what manner, and for how long. Through its convincing psychological depth and depiction of both “heavy lives and lightweight lives,” the novel achieves a remarkable, humane poignancy.

This book—Yokoyama’s second to appear in English—is an engrossing workplace drama about the Japanese newsroom. Drawn from his experience as a beat reporter, the novel centers on a real-life tragedy—the 1985 crash of a passenger plane—and follows the ethical dilemmas and personality conflicts that arise for the newspaper staffers tasked with deciding which stories to tell, in what manner, and for how long. Through its convincing psychological depth and depiction of both “heavy lives and lightweight lives,” the novel achieves a remarkable, humane poignancy.

Nonfiction Winner

Interior States

by Meghan O’Gieblyn

Anchor Books

“The Midwest,” writes Meghan O’Gieblyn, “is a somewhat slippery notion.” That may be true, but in this collection of essays, O’Gieblyn has done an excellent job of pinning down its character. Raised in a highly religious family, O’Gieblyn had a crisis of faith in college and dropped out of the evangelical church. That experience, which echoes through the collection, seems to have left her with a gift for seeing beyond the ideological veil to the other side of things. And it is this faculty that distinguishes her work: in a time when few voices are willing to engage with positions they disagree with, O’Gieblyn writes with refreshing sensitivity about subjects and institutions with which she often has foundational disagreements. The result is a searching, powerful book, full of insight and generous critical inquiry.

“The Midwest,” writes Meghan O’Gieblyn, “is a somewhat slippery notion.” That may be true, but in this collection of essays, O’Gieblyn has done an excellent job of pinning down its character. Raised in a highly religious family, O’Gieblyn had a crisis of faith in college and dropped out of the evangelical church. That experience, which echoes through the collection, seems to have left her with a gift for seeing beyond the ideological veil to the other side of things. And it is this faculty that distinguishes her work: in a time when few voices are willing to engage with positions they disagree with, O’Gieblyn writes with refreshing sensitivity about subjects and institutions with which she often has foundational disagreements. The result is a searching, powerful book, full of insight and generous critical inquiry.

Nonfiction Finalists

This Little Art

by Kate Briggs

Fitzcarraldo Editions

In a patiently constructed, charismatically approachable assemblage of essay fragments, Briggs tracks—through the grand art called world literature, underneath its memorable characters, alongside authors who are often characters themselves—the complex figure of the translator, whom she sounds out variously as a “would-be writer,” a “producer of relations,” a “maker of wholes,” and, quoting Michelle Woods, “a holistic, gendered, literary being.” Ruminating on individual word choice, on the historically contentious politics around translation as “its own experience of creative authorship,” and on each level in between, Briggs skillfully pierces the notion of transparency with which we tend to praise translations, instead inhabiting and complicating the terra nullius through which literature must pass on its way to the illusory status of universality.

In a patiently constructed, charismatically approachable assemblage of essay fragments, Briggs tracks—through the grand art called world literature, underneath its memorable characters, alongside authors who are often characters themselves—the complex figure of the translator, whom she sounds out variously as a “would-be writer,” a “producer of relations,” a “maker of wholes,” and, quoting Michelle Woods, “a holistic, gendered, literary being.” Ruminating on individual word choice, on the historically contentious politics around translation as “its own experience of creative authorship,” and on each level in between, Briggs skillfully pierces the notion of transparency with which we tend to praise translations, instead inhabiting and complicating the terra nullius through which literature must pass on its way to the illusory status of universality.

Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump

by Asad Haider

Verso Books

Asad Haider, a founding editor of Viewpoint Magazine, takes on the contentious debates of contemporary identity politics in this illuminating book. Haider cautions against reducing politics to individual performances of identity, drawing from black revolutionary theory, historical analysis, and his own experiences as a student activist to provide a lucid argument for solidarity and collective action against social and racial oppression. The book is short but rigorously constructed—every sentence instructs—and its challenge to the left’s methods of antiracist struggle cannot be ignored: for those who are part of the struggle, the stakes are too high.

Asad Haider, a founding editor of Viewpoint Magazine, takes on the contentious debates of contemporary identity politics in this illuminating book. Haider cautions against reducing politics to individual performances of identity, drawing from black revolutionary theory, historical analysis, and his own experiences as a student activist to provide a lucid argument for solidarity and collective action against social and racial oppression. The book is short but rigorously constructed—every sentence instructs—and its challenge to the left’s methods of antiracist struggle cannot be ignored: for those who are part of the struggle, the stakes are too high.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death

by Maggie O’Farrell

Knopf

You hear all the time how a brush with death can lead a person to return to, or discover, their essential purpose. Maggie O’Farrell has had seventeen (including a near drowning, a close escape from a murderer on a country path, and a harrowing delivery in which she nearly bled out). She sketches them, one by one, in this memoir, with such visceral intensity, with such emotional clarity, that perhaps her essential purpose is to write about that liminal space, that line between what we know and what we can’t fathom. O’Farrell’s prose is taut. Her scenes are almost athletic in their combination of physicality and suspense. Yet the action is tied to reflection, making this as much an essay as a lyrical memoir. Whatever you call it, this book about nearly dying is very much alive.

You hear all the time how a brush with death can lead a person to return to, or discover, their essential purpose. Maggie O’Farrell has had seventeen (including a near drowning, a close escape from a murderer on a country path, and a harrowing delivery in which she nearly bled out). She sketches them, one by one, in this memoir, with such visceral intensity, with such emotional clarity, that perhaps her essential purpose is to write about that liminal space, that line between what we know and what we can’t fathom. O’Farrell’s prose is taut. Her scenes are almost athletic in their combination of physicality and suspense. Yet the action is tied to reflection, making this as much an essay as a lyrical memoir. Whatever you call it, this book about nearly dying is very much alive.

Not to Read

by Alejandro Zambra

Fitzcarraldo Editions

This book of essays—the prolific Chilean’s first to appear in English—is an erudite, surprising, and altogether delightful read. Described by his longtime translator Megan McDowell as a “kind of literary autobiography,” Not to Read consists of fifty-five brief columns, reviews, and lectures that in sum provide a discursive, deeply quotable survey of contemporary Latin American literature—and of the reading life, more generally. “They say that there are only three or four or five topics for literature,” Zambra writes in the collection’s final essay, “but maybe there’s only one: belonging.” His effortlessly warm and engaging book belongs on as many bookshelves as possible.

This book of essays—the prolific Chilean’s first to appear in English—is an erudite, surprising, and altogether delightful read. Described by his longtime translator Megan McDowell as a “kind of literary autobiography,” Not to Read consists of fifty-five brief columns, reviews, and lectures that in sum provide a discursive, deeply quotable survey of contemporary Latin American literature—and of the reading life, more generally. “They say that there are only three or four or five topics for literature,” Zambra writes in the collection’s final essay, “but maybe there’s only one: belonging.” His effortlessly warm and engaging book belongs on as many bookshelves as possible.

Poetry Winner

Human Hours

by Catherine Barnett

Graywolf Press

This is a book populated by the kind of subtleties that make desperation and anxiety all the more palpable. Catherine Barnett asks us to consider what time and mortality mean for those who are “alive, furiously” and yet “no hardier than flowers.” These poems offer the human tenderness and intimacy that are antidotes to the contemporary tendency to avoid vulnerability.

This is a book populated by the kind of subtleties that make desperation and anxiety all the more palpable. Catherine Barnett asks us to consider what time and mortality mean for those who are “alive, furiously” and yet “no hardier than flowers.” These poems offer the human tenderness and intimacy that are antidotes to the contemporary tendency to avoid vulnerability.

Poetry Finalists

You Darling Thing

by Monica Ferrell

Four Way Books

Monica Ferrell’s newest book highlights the violences that result from traditional notions and practices of courtship, marriage, love, and possession. The poem “Oh You Absolute Darling” is deeply unsettling in its reduction of the subject to a sexual object, one that can be consumed and disposed of. Ferrell’s poems constitute a precise meditation on women’s bodies, as they are viewed, as they are endangered.

Monica Ferrell’s newest book highlights the violences that result from traditional notions and practices of courtship, marriage, love, and possession. The poem “Oh You Absolute Darling” is deeply unsettling in its reduction of the subject to a sexual object, one that can be consumed and disposed of. Ferrell’s poems constitute a precise meditation on women’s bodies, as they are viewed, as they are endangered.

Baby, I Don’t Care

by Chelsey Minnis

Wave Books

Chelsey Minnis’s latest book deploys language to reflect temporal truth, rendering every object and image as absolute and in the present. Paradoxically, though, in her view, the world remains a draft that’s up for revision. In a time when even the most basic truths seem called into question, Baby, I Don’t Care reads like a guidebook to adapting the mind: “There’s only one sensible thing to do. / That remains to be seen.”

Chelsey Minnis’s latest book deploys language to reflect temporal truth, rendering every object and image as absolute and in the present. Paradoxically, though, in her view, the world remains a draft that’s up for revision. In a time when even the most basic truths seem called into question, Baby, I Don’t Care reads like a guidebook to adapting the mind: “There’s only one sensible thing to do. / That remains to be seen.”

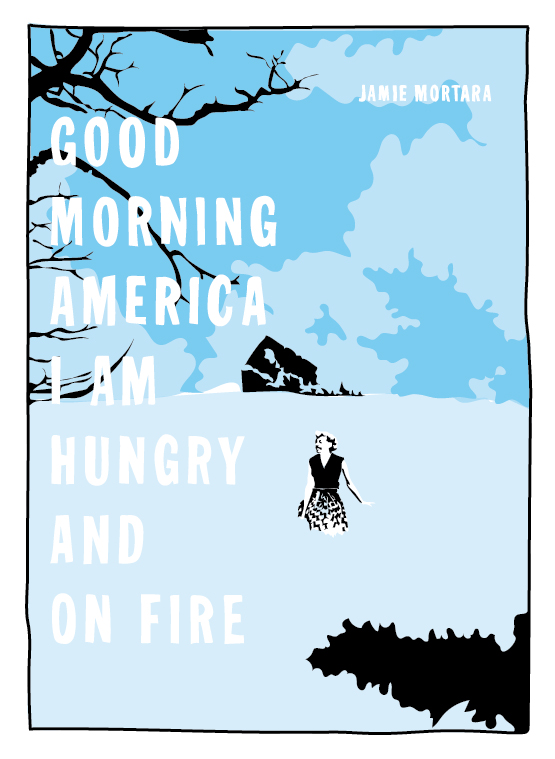

Good Morning America I Am Hungry and on Fire

by Jamie Mortara

YesYes Books

In each poem of this devastating book, Jamie Mortara helps us navigate the all-too-familiar chaos of contemporary America. Every line questions how to love and honor one’s own desires while living in a nation “on fire,” a country where catastrophe is always imminent. We have “all stared into the night enough,” Mortara writes, “so this is a flower / that I grew in the backyard / it’s called Surrender.”

In each poem of this devastating book, Jamie Mortara helps us navigate the all-too-familiar chaos of contemporary America. Every line questions how to love and honor one’s own desires while living in a nation “on fire,” a country where catastrophe is always imminent. We have “all stared into the night enough,” Mortara writes, “so this is a flower / that I grew in the backyard / it’s called Surrender.”

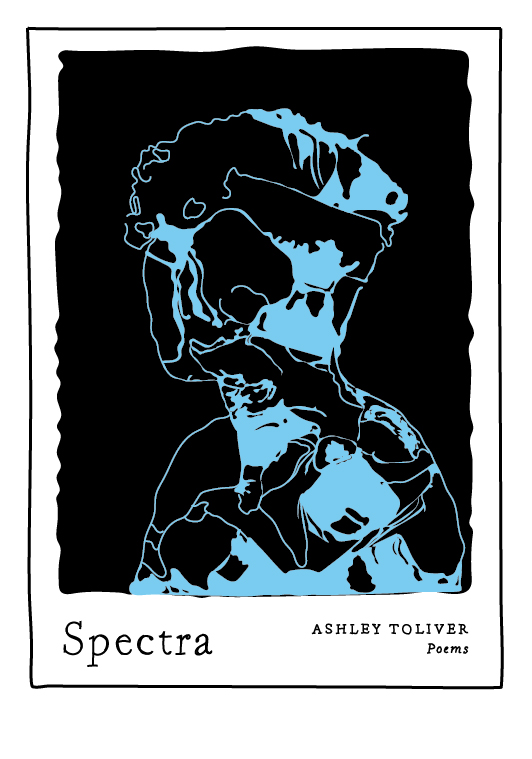

Spectra

by Ashley Toliver

Coffee House Press

Ashley Toliver’s first full-length book, Spectra, showcases her ability to articulate the infinite that exists within the personal. The sentences here investigate the numberless contact points between the self and the beloved, the self and the limited imagination of those who encounter that self: “I still don’t know what kind of woman / I am. But as the flame nears the fingers / that trust the match, as close as the skin / can stand it to singe, I call this the nerve / to find out.” This book is relentless.

Ashley Toliver’s first full-length book, Spectra, showcases her ability to articulate the infinite that exists within the personal. The sentences here investigate the numberless contact points between the self and the beloved, the self and the limited imagination of those who encounter that self: “I still don’t know what kind of woman / I am. But as the flame nears the fingers / that trust the match, as close as the skin / can stand it to singe, I call this the nerve / to find out.” This book is relentless.