I.

In Chicago, I had a friend whose mother died when she was young. By the time I knew her she had long since finished mourning, but she had not yet overcome the need to mourn. I never saw her more disturbed than on the day she realized, late into the evening, that it was the anniversary of her mother’s death. She had nearly forgotten. I never saw my friend cry for her mother but I saw her cry for her guilt.

These guilty mourners are everywhere. Go online to forums for the grieving, to the back pages of self-help guides to bereavement, or to the case studies of psychologists specializing in loss, and you will discover a great number of people in the wake of tragedy worried that they are heartless freaks. They worry because they believe they are getting over total disaster with too much ease. The world has changed forever, they insist, but they keep forgetting. Their husbands are dead, they report, or their children are paralyzed, but all they can think about is the laundry. Many report similar guilt over their responses to national catastrophe. The shooter is still active but they are worried about traffic. The monster is still President, but they wish the store was open on weekends.

“If it helps,” one woman writes on a message board, “My first response to 9/11 was thinking, ‘Oh this is really going to fuck up my date tonight.’” The towers were still burning on television.

On forums, everyone is asking the same question: Is there something wrong with me? The question is so common that if it is a sign of mental defect, then there are very few of us, it seems, who escaped ruin at the factory.

II.

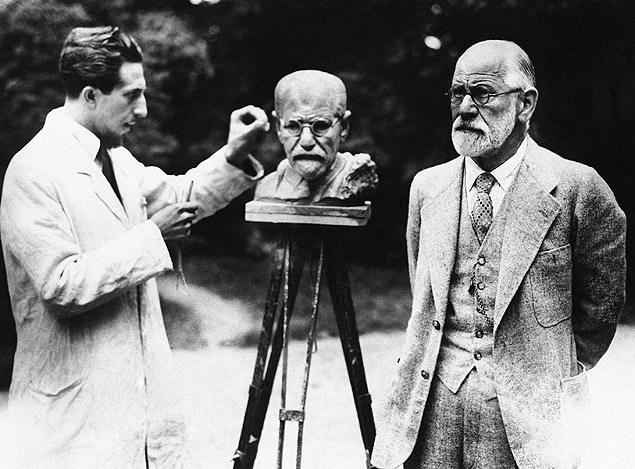

“In what, now, does the work which mourning performs consist?” Sigmund Freud asks in Mourning and Melancholia. “I do not think there is anything far-fetched in presenting it in the following way. Reality-testing has shown that the loved object no longer exists, and it proceeds to demand that all libido shall be withdrawn from its attachment to that object. This demand arouses understandable opposition—it is a matter of general observation that people never willingly abandon a libidinal position, not even, indeed, when a substitute is already beckoning to them. This opposition can be so intense that a turning away from reality takes place and a clinging to the object through the medium of hallucinatory wishful psychosis. Normally,” however, “respect for reality gains the day.”

Grief, for Freud, was a dilemma. When what we love is lost, all we have left of it is our sorrow. We “turn away from any activity that is not connected with thoughts of [it]” Freud writes. We lose our capacity, Freud says, to adopt any new object of love, because to do so would be to surrender and betray the last remaining token of our love. Healthy mourning, says Freud, is the process by which we must divest the dead of their importance. This divestment comes piecemeal and provokes guilt, but it is necessary. The redirection of the conscious mind to mundane concerns is the work of mourning. If it comes quickly, all the better. “It is remarkable that this painful unpleasure is taken as a matter of course by us,” he writes. “The fact is, however, that when the work of mourning is completed the ego becomes free and uninhibited again.” It worries about dates and laundry.

For Freud, the only alternative is melancholia. The melancholic cannot displace their love onto another object. Instead, they swallow their attachment and turn their own ego into the lost love. They debase themselves and degrade their own importance because they cannot bear to do it to what they’ve lost. They denigrate their own moral character, find themselves broken and worthless things (what, after all, are these guilty mourners doing?), and the work of divestment becomes the work of self-destruction. Melancholia is the failure to mourn. The result, sometimes, is suicide.

III.

Freud, of course, was literally wrong about everything. This does not mean that he isn’t useful as metaphor.

The guilty mourner is troubled, more troubled than they are by death itself, because there is something narratively backward in their healing. The simplest rules of storytelling demand that events produce consequences commensurable to their scale, follow rational progressions like John wants X, but Y happens, and therefore Z results. The inciting incident is followed by rising action. An affair ends the happy marriage. The death of the father brings the family back home. An alien invasion unites the nations of Earth. If the consequences surprise us, that is fine, even desirable. But if they are inadequate then they are incomprehensible.

Freud comforts us with an alternative. The hero struggles to return to normal. The return of the mundane is not the failure of action but the action itself. The villain is the pit of melancholy and the stakes, quite possibly, are death. We aren’t so bad after all. We aren’t so guilty. We can work with this story.

IV.

When the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, the survivors faced a catastrophe not only beyond what even our most depraved language can capture, but a catastrophe for which there was no language. This species of violence had never happened to anyone before. Outside the upper echelons of the American military, this was not a violence anybody knew to be possible.

Even in the aftermath, even on the day of the bomb, hours after an explosion whose victims could not explain, we see the intrusion of the mundane.

“Although Dr. Fujii’s shoulder was by now terribly painful, he examined the girl’s burns curiously,” writes John Hersey in Hiroshima. “Then he lay down. In spite of the misery all around, he was ashamed of his appearance, and he remarked to Dr. Machii that he looked like a beggar, dressed as he was in nothing but torn and bloody underwear. Later in the afternoon, when the fire began to subside, he decided to go to his parental house, in the suburb of Nagatsuka.” Amidst burns and fire and misery, Dr. Fujii worries that he is inappropriately dressed.

It is not difficult to mistake these moment for bathos. The Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto, another of Hersey’s subjects, wanders down a ruined street toward the center of the burning city. He saw, “as he approached the centre, that all the houses had been crushed and many were afire… under many houses, people screamed for help, but no one helped.” He runs past them, muttering a prayer. Then he encounters his wife.

“He did not embrace his wife,” writes Hersey. “he simple said ‘Oh, you are safe.’” They speak for only a few moments, and then go their separate ways, “as casually—as bewildered—as they had met.” Tanimoto continues toward his church, toward the fire, toward an apprehension of the immense strangeness that the city has just endured. Taminoto is more bewildered by his family. After all of this, it is odd to remember that he has an ordinary life. But he does.

The mundane returns immediately, and at once, even in the wake of an a-bomb. I am wondering whether it is as terrible a struggle as Freud tells us. I am wondering if our minds are not a little bit too healthy.

V.

“We sit in the darkening living room, smoking and sipping our cups of whiskey,” Jo Ann Beard recalls in her essay The Fourth State of Matter, “Inside my head I keep thinking Uh-oh, over and over. I’m rattled; I can’t calm down and figure this out. ‘I think we should brace ourselves in case something bad has happened,’ I say to Mary. She nods. ‘Just in case. It won’t hurt to be braced.’ I realize that I don’t know what ‘braced’ means. You hear it all the time, but that doesn’t mean it makes sense. Whiskey is supposed to be bracing, but what it is is awful.’

Something bad has happened. It is Friday and with little to do in the physics department where she is employed, Beard has left work early. She is distracted by the recent departure of her husband and by her dog, who is growing old and ill. Shortly after her departure, a graduate student armed with a .38 caliber revolver murders five of Beard’s colleagues, and then shoots himself.

Beard knows, I think, the baffling speed with which these intrusions are subsumed by the mundane. Nearly halfway through the essay, an essay concerned with the small difficulties of home ownership and middle age, the world changes. When the shooting comes, it is a brief intrusion. It is a brief atrocity, dispassionately related in a single section, upending the whole essay. After the expected outbreak of denial and terror and grief, Beard leads us back to where we started, to the couch where she’s been sleeping. Her husband still gone and her dog still sick, just as they were before.

We don’t struggle over the pit of melancholia, tempted by our grief. Ordinary life can’t help digesting tragedy. The mundane sees the alien and consumes it, just swallows it up, and if we feel guilty when it happens, perhaps this is not a distraction but a sign.

VI.

Hersey carries the mundane into the alien. Beard sees the alien smothered by the mundane. Despite these opposite movements, both accounts are considered successful. Both appear “true” in the sense that both appear to reveal in literature some essential fact about human minds. How? What story are we working with?

We have been talking about loss as if it occurs in discrete moments, tugged at, for better or worse, by the baseline. Despite the sense that this ought to occupy the whole of our attention and action, we find ourselves fixated on small things—unable to escape strange worries like their clothes, or their sick dog, even in the face of a horror like the atomic bomb. These banalities are at odds with whatever catastrophe is at hand, and the fixation on them functions as a distraction, or as a necessary element of mourning, or as a sin, until the catastrophe can be processed and absorbed into a reunified experience of life. But what does such a reunification really entails? In Beard’s telling, it is something like a reversion, the inevitability with which normal life will absorb disaster and carry on—one returns to the mundane because there is nowhere else to return. In Hersey, we have the opposite suggestion: life goes on, but there is no “return” after something like the atomic bomb. The new life is not the ordinary old life, even if some of its daily concerns limp along with you into the future. In Freud, we are just struggling to conform to our “reality checks”, whatever reality entails. In every case, either return is possible, or, perilously, it is not.

At bottom, I suspect that we are not really certain which of these things has happened; not really certain that they are even different things. This, at bottom, is what terrifies. The mourner who asks, Why am I so preoccupied with the normal? is asking, really, Is this normal now?

VII.

Freud is careful to note that real death is not the only cause of mourning. It is sometimes a loss of a moral ideal kind. “The object has not perhaps actually died, but has been lost as an object of love (e.g. in the case of a betrothed girl who has been jilted)”, or the loss is of “some abstraction that has taken the place of a loved person, such as one’s country, liberty, an ideal, and so on.”

These alternatives differ for Freud in their particulars, but not in their loss. They are all dead, or as good as dead. The reality-check cannot be appealed. Now all that remains is to divest. He allows, briefly, that a patient may not fully accept the finality of their loss, but this, like the temptation to melancholia, is only another obstacle for the clinician. Freud wants to know how to treat it. I am wondering how our wounded egos know when what we love is truly dead. After a shooting, after the bomb, after the loss of an ideal, they do not seem to stop and check. They have the painful work of forgetting to attend to. They seem so eager to get started.

If the loss is not irrevocable, then divesting is not healing, it’s just apathy. If the mundane smothers every shock, then the ego is only liberated from its duty. Perhaps that’s where we want to be, in failure, and in sin. Perhaps that is normal. But we are talking now about a menace, and our guilt is a warning, not a trap.

VIII.

Let us run a reality check. We mourn too little, not too much. Bodies are forgotten everywhere. Some are the literal corpses of children, shot in dozens of schools since Iowa. Some are the bodies of prisoners and refugees in the shadow of dead ideals. There were no words for the bomb once, and even with Hiroshima we hardly have words still. They’re normal now, safe if we don’t use them.

We elect a monster, and even the comfortable are eager to ‘resist’, so long as it does not interfere too much with their lifestyles, so long as it doesn’t take too much time from the garden and the grocery store, and the kids. The oceans boil and the land turns to desert. The planet is dying, we say, but we have already begun that healthy work of mourning: we’re going to lose it, we know, it’s better, Freud might say, to divest ourselves into jokes and nihilism now. Your mental health is what matters. Every child starving and wedding party incinerated and farmland turned to desert by the production of our comfort is just depressing to think about too much. Take care of yourself.

It is amazing that we find mourning so painful when we’re aware of it. We’ve become so good at divesting our loses of importance, it’s a wonder we’re aware at all. Has the world changed so much and so suddenly that I can no longer even feel the difference? the guilty ask. The answer is yes, and it is happening, has happened, all the time.

There are delusions far more powerful than melancholia. The alien isn’t the trouble, the mundane is. The trouble is whether we become so adept at Freud’s mourning that we do no mourning at all, have no period of bafflement or guilt. “The water sure is nice today,” says the swimmer to the fish. The fish says, “What’s water?”

IX.

I lose my friends in the morning.

When I wake up in the morning I lie still in my bed. Not yet adjusted to the light, I try to remember, slowly, who I am.

I. reconstruct the inventory of particulars, try to control the speed that they come back to me, try to interrogate each fact in the cold light of day while the day is still cold and I haven’t yet adjusted to the light. It is easier, in this way, to accept whatever comes with clarity. What often comeson many days is that I’ve lost another friend. I wasn’t sure the night before but I see that clearly in the morning. We aren’t just having a fight, we haven’t just been out of touch, nobody will even bother to apologize, nobody will ever bother to apologize. They’re gone. . I ready my legs and I remember every step that led away from friendship. I place this story in the file with every other story that I’ll reconstruct on every future morning. Then I get up.

I have lost nearly every friend I’ve ever made. They go one by one, usually, a new one every few weeks. Sometimes they go all at once, a whole social circles vanishing overnight. I do not tell you this in search of pity. It is just how I’ve found my life.

I used to struggle mightily against these losses. But after too many years and cities, the struggle exhausted me. For a while, I mourned each one. Then, some day after I came to the small town where I live these days, where I did not even bother to persuade myself I was coming to a fresh start, I stopped feeling anything about these loses at all. My ego has prearranged its divestment. It comes without difficulty. I lay still in the morning and know what I’ve lost, and there is no question of whether or not it is irrevocable, really, because already I’ve moved on. I am the picture of mental health.

I lose friends because I am prideful and I am easily wounded and this is a terrible combination. I am terribly stubborn but even this is the most tolerable scenario. More often, I am the one who wounds. I am selfish and petty and vengeful, and even when I can pretend for a while that I am not, I am only ever loyal in the wrong way. I was never taught to be calm. When I am loyal, I am loyal like a dog, rubbing you the wrong way until there’s fur all over the legs of your best pants, until I’m pissing on your best shoes, until I take your last best attempt to explain how I’ve hurt you in the worst way possible and I say every nasty thing I ever thought while I was pretending to be loyal all those years. I am loyal to a fault line. This too is a terrible combination.

It is my fault. I could mend these tears, but I don’t.

I recite the liturgy of my failures because I want to need to act on them again. I am trying to relearn my melancholia. That is the task: to live again and longer in our forgetting and our guilt.