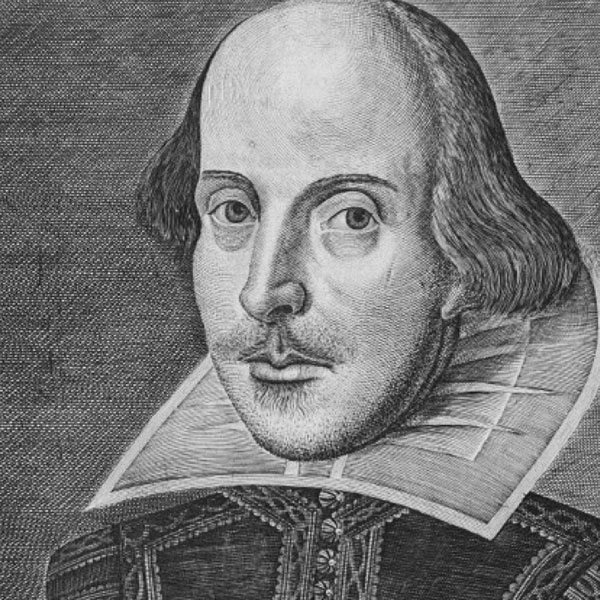

For a writer who passed away four hundred and one years ago, it’s amazing how beloved and relevant the works of William Shakespeare still are for us. The most popular dramatist of his day was Christopher Marlowe and the greatest argument for the ascension of one against the waning of the other can be made about the quality of the writing itself. Anthony Burgess is known to have once opined, “It is assumed by most of us that Shakespeare is the greatest dramatist in the world… but take the poetry and the incredible psychological insight away and you have artificial plots that were not Shakespeare’s own to start with, full of improbable coincidence and carelessly hurried fifth-act denouements.”

No matter how you dress up a Shakespearean production, what matters most in his work is the words. Even at the poorest performances of a stripped down play with nothing to dazzle an audience anywhere, you should still be able to close your eyes, block out everything else, and revel in the writing.

Burgess supported this thesis this when he wrote his brilliant novel, Nothing Like the Sun, about Shakespeare’s life. For one of the most famous writers in human history, we know conspicuously little about Shakespeare’s life, so little that people have theorized that William Shakespeare might not actually be the author of the works of Shakespeare. Burgess doesn’t delve into conspiratorial territory, but he does fill in the gaps with his own hypotheses. The brilliance of Nothing Like the Sun, however, rests on the linguistic might of Burgess, the man responsible for such works as the novel, A Clockwork Orange (which features the slang language Nadsat), and who wrote the “language” of the pre-historic people in the movie, Quest For Fire (which mostly consists of grunts). His novel of Shakespeare’s life is full of puns and linguistic games and told through an Elizabethan-voiced third person narrator, play-structured dialogue, and Shakespeare’s imagined stream of consciousness journal entries. One of the best examples of this last form is when Shakespeare must come up with the play A Midsummer Night’s Dream in time for a commission:

And so I lay on my back a space and watched the fire sink to all glowing cavern and it was like a dance of fieries, I would say fairies. And then came the name Bottom, which will do for a take-off of Ned Alleyn, so that I laughed. Snow falling as I sat to work (I cannot have Plautus twins for most will have seen C of E but I can have the Pouke or Puck confound poor lovers) and the bellman stamped his...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in