By the time the Academy Awards approached, in 2018, The Shape of Water had been accused of plagiarizing a fifty-year-old play as well as being “basically a remake” of Creature from the Black Lagoon. Still others pointed out that the romantic fantasy drama—about a janitress who falls for a humanoid amphibian—had ripped off plot points à gogo from Splash.

I read and watched with interest. Atmospherically, the Ron Howard- and Guillermo del Toro-helmed pictures were as different as their directors: one a cute caper, the other an R-rated fairy tale. Splash (1984) had only been nominated for Best Original Screenplay. Shape was up for fourteen Oscars and grabbed four of them. But I wished more credit had spilled over for the effects. Because while Shape’s river critter was the result of both practical FX and computer work—the actor wore a full-body suit exquisitely conditioned by a digital wand—Splash’s half-fish was convincingly faked in a pre-CG world, just before the tech revolution. It’s still the best mermaid costume to date.

“One of the reasons Splash is so special is that the movie was groundbreaking stuff—though, the audience didn’t know it,” said Robert Short, the special effects artist tapped for E.T.’s glowing heart, who afterward worked out the iconic mermaid tail.

It was not as if siren pictures had not been done. Both Miranda and Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid dropped in 1948. “What can you do with a mermaid, supposing you’ve got one in your house—or in a motion picture comedy, which is an equally difficult spot?” The New York Times’s film critic asked then. But the early eighties was a moment betwixt and between, liminal like the creatures themselves, when crude motion control rigging was available—and HD was on the horizon—but technology was not yet good enough to conjure something wholly with computers.

“People didn’t realize what computers could do for film until around the time of Beetlejuice,” Short, who went on to win an Oscar for the 1988 cult classic’s makeup effects, explained from Malibu on a call. It was a decade before Jurassic Park blended animatronics with computer graphics, when the craft of analogue special effects in Hollywood was clutch, and to bring myth to life onscreen—and make folks believe in mermaids—you had to experiment.

“There weren’t really advanced tools. There weren’t really off-the-shelf solutions—there weren’t a lot of options,” Mitch Suskin, the production’s FX boss, added. Faking the underwater scenes with blue screens or miniatures was a nonstarter. “We knew,” Short said, “that the tail had to be functional.”

“Swimmable,” Suskin clarified.

Suskin had coordinated effects on Poltergeist and E.T. It was Suskin who had asked Short to troubleshoot the alien’s ticker. “They had the finger figured out,” Short said. He was a creature designer with a stunt background and underwater expertise—who’d done the Jaws-inspired B horror comedy Piranha, by the future director of Gremlins—and Suskin put him up to lead the tail end. “How fishy was she going to be?” It was a question, Suskin said. “We started looking at concepts before we had direction.” After going to the aquarium to watch fish, Short had sketched a mermaid who was evolutionary in form: a gray-skinned, “dolphinesque” thang that director Ron Howard rejected as “too monster.”

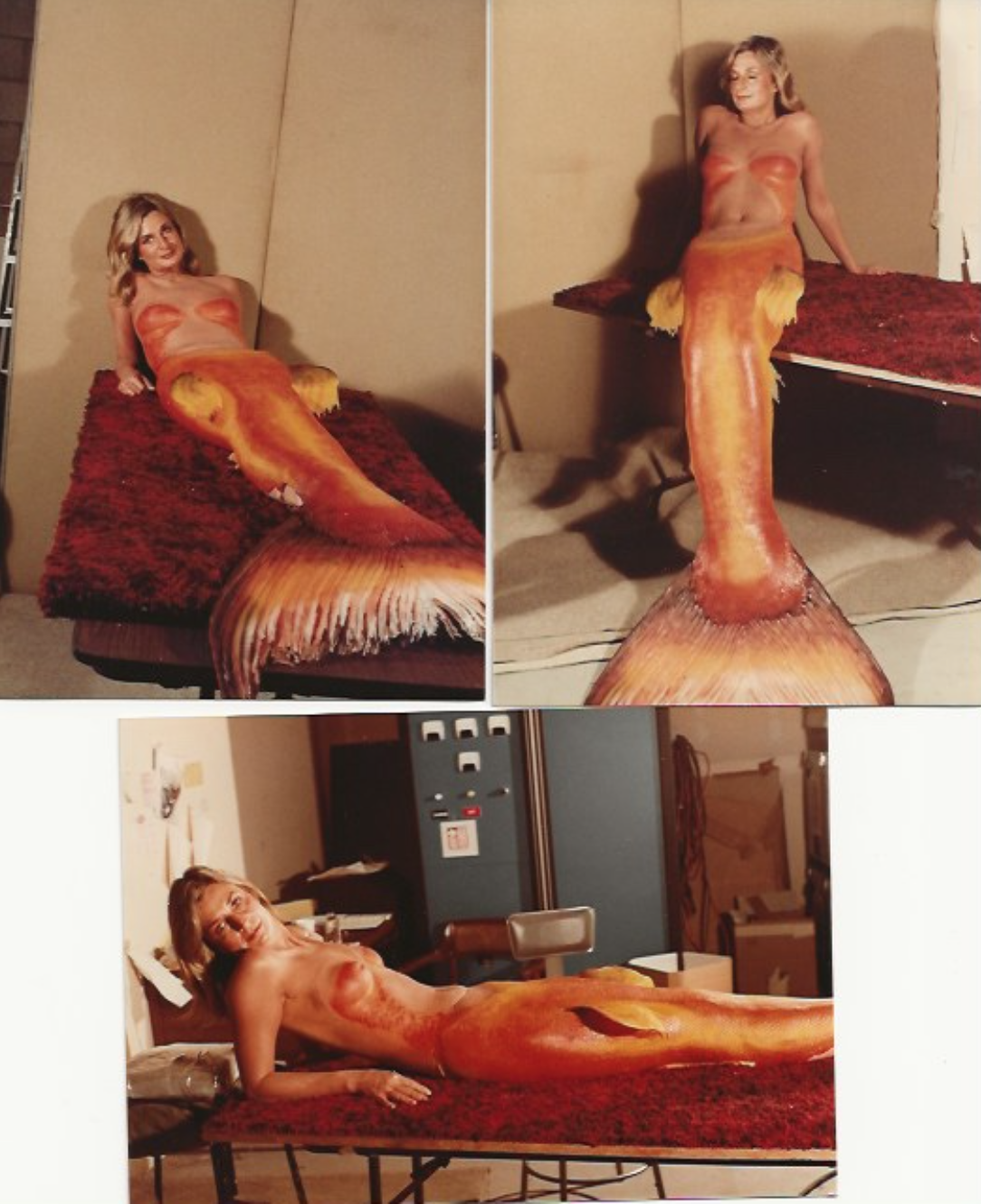

“Ron wanted pretty,” Karen Kubeck, the Joe Blasco-trained artist who designed the heroine’s underwater makeup, remembered. He envisioned a tropically bright fin that moved with mystery and elegance. “Ron wanted orange,” Short said. Playing Madison was Daryl Hannah: her eyes were glacial; her hair, kinked, butt-long rays of sunshine. And she’d have this lower half—except when she followed Tom Hanks home to New York City—“like a koi.”

Because Splash was being made by Disney, it was also by now obvious how to treat the twenty-five-year-old starlet’s top half. Short prototyped a tail that scaled up over the breasts, “as if an evening gown,” Kubeck said, laughing on the phone. “You know, breasts are buoyant under the water. In a pool test, they tugged at the material and made it obvious that this was a costume.” Anyway, Short thought everyone found it “a little too Disney.” In fact, the company had had enough of teenagers and young adults spurning its movies at the box office. Disney announced Touchstone Films: a more mature side label with a mandate to do PG-rated flicks such as their launch piece, Splash.

Though Disney promoted Splash as “a sensuous love story,” and the story had a big dick joke, the boobs were not moot. “Even at Touchstone, it was touchy,” said Suskin. (Last year, when the movie went to Disney Plus, the streaming platform censored Hannah’s tush by digitally lengthening her tresses to ridiculous effect.)

“So,” Kubeck said, “I just put round band-aids on her nipples and we taped her hair to her chest.” Bob Schiffer, the late head of Walt Disney Studios’s makeup department, had two-part wigs made when he could not find one as super-long as Howard prescribed. He found that synthetic and not human hair flowed better in H2O.

“The early eighties was still the era when you didn’t know what you were going to use to make something,” Short told me. “It was a very creative time, before the industry segued in the nineties to having special effects supply houses where someone could tell you to grab item X from aisle A.”

Decades before, across the Atlantic, for Miranda, Glynis Johns had wiggled into a rubber fin forged by the hot-water bottle and tire firm Dunlop. It floated awfully when she got into the tank. “Meanwhile, I lost my boosie bits,” the British actress recounted later, referring to the hair extensions that were similarly fixed to her bust. “They came unstuck.” Ann Blyth’s piscine part in Mr. Peabody was carved rubber, coated in latex and weighted with BB gun pellets. That black-and-white picture had budgeted $500 and three weeks for tail-making, but it cost $18,000 and took Universal’s makeup master Bud Westmore and his underling Jack Kevan thirteen weeks to deliver. (Westmore was the cad who stole the kudos from Millicent Patrick for designing the Gill-manin Creature from the Black Lagoon, which Kevan went on to copy for The Monster of Piedras Blancas.) “The most ambitious makeup job ever to be performed on the nether extremities of an actress,” Life reported.

“I didn’t know anything about their difficulties,” said Short. He tried foam-filled latex. It floated and bubbled and wrinkled—“like cellulite,” Kubeck said—and fell apart in the pool at Suskin’s apartment building. He tried Smooth-On, a standard then and now. But the substance was oily and sweated off paint. Someone suggested casting the tail in a urethane product Johnson & Johnson had just introduced to the market for Band-Aid, called Skin-Flex. It was finding application in theme parks animatronics—another thing split between the ancient and the modern, part makeup and part computer.

“Skin-Flex was puzzlingly unpredictable, but unless unpainted and exposed to sunlight,” said Short, “we discovered that it never degraded!” By trial and error, plus luck, they worked out sea-going orange tails with lacey, tattered dorsal and tail fins that trailed wraithlike. (A paint with genuine fish scales stirred in proved too dull at depth.)

Hannah’s base makeup was another matter. Short had telephoned the granddaddy of prosthetic makeup. “Dick Smith was the guy if you had a problem—but he had no ideas for a waterproof cosmetic that would survive shoots under the sea.” Every product Short’s team tested, saltwater ate off. Kubeck thought back to Covermark. Patented by Lydia O’Leary in the thirties, it was the original cosmeceutical, favored by women for masking birthmarks (and bruises), but Kubeck had fallen on the product as a girl for the dark circles under her eyes.

Kubeck had worked on low-budget sci-fi and horror pictures, such as Parasite, starring Demi Moore. “This was the era of teen movies, punk makeup, comedy, and gore,” she summed it, and the contents of her kit included gelatin, Epsom salt, blood tubes, and bald caps. “But this was romance,” she said. “I never knew what a bronzer was until Splash.” She’d heard a Goldfinger actress had suffocated from wearing body paint that blocked her pores. (“A myth, I later learned.”) In any event, she bought pots of Covermark and mixed in colorants and attached fine, loose glitter to get an aureate tan. “If you put it on thick—it was thick enough to write your name in—one thing held the other up and it all stayed.”

Getting into mermaid makeup kept Hannah in a chair for what she’s claimed was eight hours, while the team glued and painted. “It probably felt like eight hours,” Short allowed. “We would’ve been fired if it took that long. It was an hour and a half!” Because Kubeck was not union, her colleague Bruce Hutchinson made up Hannah on the shoot. (Kubeck is now union, in addition to being a Santa Monica-based aesthetician whose clients call her the “eyebrow whisperer.”) Schiffer scuba dove to adjust Hannah’s wig and retouch her makeup underwater. Once she was in the tail, she was entailed all day.

The citrus-toned appendage weighed thirty-five pounds. And pinched. And obliged the actress to pee herself. But it worked. With a flick of diaphanous fluke, Hannah propelled through the Bahamian waters, near Nassau, where the undersea shots were filmed over three weeks.

It helped that Hannah had been enamored of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” as a girl. That she used to tie her legs together and practice in the pool for hours and hours on end: now, the actress could act in agua while holding her breath for north of a minute. “I had my mermaid swim down,” Hannah said. She out-swam the safety divers—and even local marine life fell for the result.

“Daryl was the biggest fish in the area. Barracuda would give us distance,” said Short. Suskin remembers Short popping up in the topaz, yelling “Oh my god, there are pilot fish!” The hangers-on wanted to glean ectoparasites from the mermaid and eat the fries offered to her from the boat by the cast and crew.

“The tail was so convincing,” Hannah has recalled fondly.

“She was half of the success of the effects,” said Suskin. “We’re proud of the tail we built, but when Daryl was in the water, there was a mermaid. That used to happen in the classic monster movies, too. You’d forget they’re not the thing that they’re suited up as and playing. Sometimes,” he said, “I’d catch someone petting the tail, like you’d pet a dog. You could forget. That’s the allusion. That’s what you lose when the actor only becomes that thing in digital postproduction.”

Hannah was willowy, with wide shoulders and genetic lottery angles, and the tail, “like a butterfly’s wings,” Pauline Kael enthused in The New Yorker (in an overall lukewarm review), seemed “to complete her.”

Today, Short still operates Malibu Mermaids, a go-to for set marinewear and aqua consultation. As a maker of tails, he has performed a lead role in the recent mermaid movement, which has particular resonance in the transgender community. (Short will also rent a life-size adult dolphin head—the one used in Ace Ventura Pet Detective. A puppeteer and assistant are included in the rental price.) “I see it a lot when people get into their tail and look down at themself,” he told me. “And for an actor, it’s something to be synced like that. You’re not in a CG suit covered in dots.”

For the submerged camerawork, Splash had Jordan Klein, Sr., the legendary aquatic cinematographer who had invented the first housings to take cameras underwater, and whose credits included 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Creature from the Black Lagoon, Flipper, Thunderball, and Jaws. “Commercial underwater sound wasn’t around. We had hand signals”—he’d developed them for Flipper—“and the ‘telephone booth,’” Klein, who is 95 and still diving, said via FaceTime from his lakeside home in Central Florida, not far from where he’d built the set’s eighty-foot wrecked Spanish galleon. He and Howard ducked into the “booth,” which was an upside-down aluminum air chamber, whenever communication broke down.

Short’s team made seven tails. Two for Hannah as Madison. Two for her stunt double, who was not once used. A puppeteered tail for Madison as a merchild, who meets Tom Hanks’s yokely character as a boy in Cape Cod. A polyfoam-filled one to slap stuntmen with. And one impromptu lightweight model for their swimming choreographer Mike Nomad, who was pressed into service for the scene when Hank’s Allen turns his back to the shoreline, just missing the foam femme’s dolphin leap.

Klein engineered a pneumatic ram to get the shot. “There’s a perfect example of old-timey effects versus CG,” Short suggested. “For that today, the whole character would be CG. Her splash might be a real water splash, just to give it some weight, and then you’d comp it all together.” In Splash: “That’s real, timed stuff that really happened in real time. Tom’s facing the ocean; you’ve got a stuntman breathing off a tube underwater, waiting for his cue and for the effects people to blast him into the air; the camera folks are angled. It’s various departments assembling to create one great shot.”

In the other pivotal scene, Madison—in human form—sneaks away with a can of salt to her beau’s tub, where, in semidarkness, she indulgently becomes a mermaid again. She becomes herself. “The script indicated a transformation. Ron loved the transformation,” Short remembered. “But when I read the script,” Suskin said, “it described the change with ‘bones crunching.’”

Werewolf flicks such as The Howling had established a tradition of using quick cuts and sound effects for transformations. “They tended to be pretty horrific,” Short explained. “It was tonally very wrong,” said Suskin. He went to his typewriter and reworked the scene into something dramatic but lyrical. Howard dug it, and Suskin and Short mulled over how they would effectually switch from leggy to leviathan. “We figured the opposite of quick cuts is one long take,” said Short. They went back to their director with the gag’s basic beats storyboarded for a continuous shot—five minutes that took one nineteen-hour day—that sees Madison’s soft thigh flake and her fluke unfold like a Fruit Roll-Up.

When Allen tries to walk in on her bath, Madison scrambles to blow-dry away her fishy anatomy. Why wouldn’t she let him in? He wants to know. “I was shy,” Madison says. How could she be shy after their sexapades? Allen wants to know. “I was shy,” she repeats agitato, sounding both ashamed and untamed, and though it does not feel like the filmmakers were trying, the exchange that transpired there in Splash is as good as anything in Shape, thanks to the transformation.