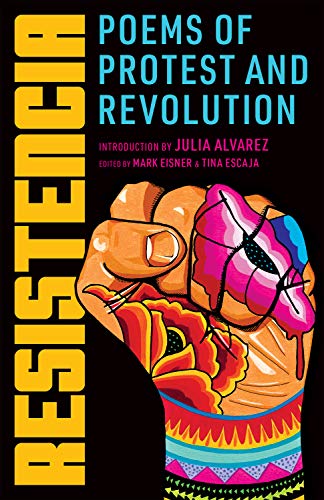

Last month Tin House published an anthology that feels poignantly tailored to the times—Resistencia: Poems of Protest and Revolution, edited by Mark Eisner and Tina Escaja. Featuring fifty-four poets, translated from Spanish and Portuguese, the book brings together, as Julia Alvarez writes in her introduction, “a diverse brigada Américana, armed with weapons of mass creation.” Their voices—and verses—are impassioned and aggrieved, sometimes irreverent, and always moving. At bottom, they are all pushing toward hope, toward a better world that we all need.

—Aaron Shulman

THE BELIEVER: What does “resistencia” means to you?

JAVIER ZAMORA: Resistencia comes from the root word resistere, to “hold back.” In a way it’s an oxymoron. It’s art’s role to show us the oxymoronic qualities of the word, by that, I mean it’s art’s role to tell us/show us what exactly is holding us back as a species. Be it poetry, art, music, it’s artists’ role to show us the old ways in which the world as we know it is no longer working AND to offer something different. Resistencia to me, therefore, is to soñar, to dream.

NEGMA COY: Our grandmothers and grandfathers, our ancestors, have resisted for centuries, and bravely cleared the way for us to continue planting and flourishing today.

For hundreds of years our mothers and fathers kept the cultural elements of our peoples alive through their strength, struggle, and love. In my case these are the Kaqchikel language that I speak and write, the clothes I wear, my spiritual practices, the arts whose essence we speak. We continue to practice these and we continue to value them. Despite the many ways in which others have tried to disappear my culture and my people, we continue to keep our essence alive.

Our grandmothers and grandfathers, our ancestors resisted racism and discrimination for many years. This isn’t something that’s only happened in the past few decades, it begins with the colonial period, and with it came genocide, epistemicide, ecocide, and femicide, among other kinds of violence that have trampled the rights that we have as Indigenous Peoples. That why it is important that our words and the actions we take in our own lands help us become the voice of our sisters and brothers who have been silenced and disappeared, that they help us denounce injustice through our writing, and protest our being oppressed by a system that is full of lies.

Beyond speaking about resistance, right now I also want to underscore that we have our own way of life. Personally, through the art that I create I want to help plant in girls, boys, and young people a respect for life, for Mother Earth, for water, for animals, for natural resources, for all of the beings with whom we live in this space and time. Of course, we also need to keep in mind the need to maintain our historical memory and stay vigilant, true to our roots and our struggles. That’s how our mothers and fathers did things, and they did it a number of different ways, and we must continue to pass down this knowledge. It’s a commitment that we can’t set aside or ignore.

We have to bloom despite our polluted society and keep our spirit alert as we fight for the future and for life itself….

—Trans. Paul M. Worley

KYRA GALVÁN: Today, more than ever, I think that poetry is rising up as a necessary cultural and social activity as we withstand the test that this little virus called COVID-19 has imposed on humanity. Many things have changed in our daily lives and we’ve had to confront solitude, the lack of human contact and, obviously, sickness, death and violence against women.

Poetry, then, becomes necessary as a way to push back against isolation, depression and persistent domestic violence.

Poetry is, and always has been, a form of resistance. Of expressing opposition, of fighting back and of rejecting political dictatorships and corrupt practices. Also the senselessness of war, labor inequity and injustice against the disenfranchised and the vulnerable.

Once again, poetry raises our voices in the name of those who suffer and of those who fight back, resisting.

—Trans. Jessica Powell

FERNANDA GARCÍA LAO: Resistance, from the Latin resistere, is the quality of remaining firm and in opposition. Of standing up.

Art and politics need this quality, which is collective, in order to say no.

No to injustice, no to silence.

To actively resist like an unconquerable stronghold, that is the power of the poetic word.

I wrote my “Decriminalizing Poem” in a full-fledged fight for the legalization of abortion in Argentina.

I read it on a stage surrounded by colleagues, in front of thousands of woman, standing up, fighting for their rights.

Alongside us, the National Congress was in session.

The law did not make it through. The poem did.

Laws always arrive late.

—Trans. Jessica Powell

CARLOS AGUASCO: I understand “Resistance” as the series of actions that seek to create more just societies, that is, the struggle for systems that are balanced in favor of the human being. What today is known as “Supermodernity,” which I’d call “post-human capitalism,” is a force that seeks the astronomical accumulation of resources into the hands of corporations and the elite, for whom drones and digital bots are more important than people. Through the automation of private life, the elites hope to consolidate their power. From my point of view, poetry is the human bastion in defense of the truth. We resist through the poetic word because it’s our way of being and of doing in the world.

—Trans. Jessica Powell