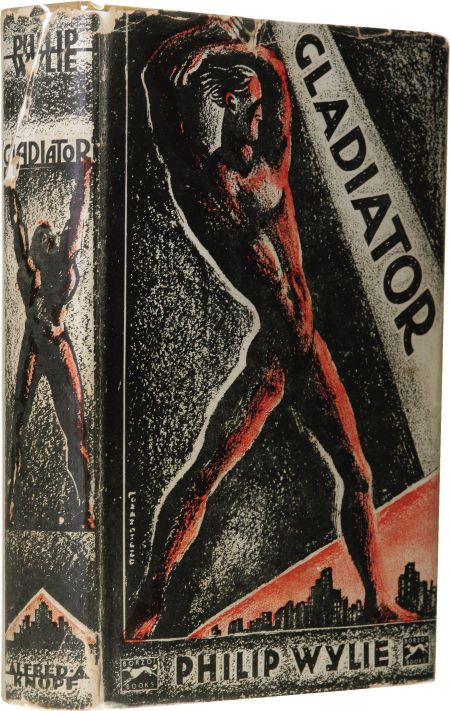

In Philip Wylie’s 1930 pulp novel Gladiator, a scientist living in a small town in Colorado develops a serum designed to reorganize the genetic structure of any living animal. Creatures injected with the serum are imbued with super speed, super strength, and are impervious to physical injury. He injects his pregnant wife with the serum, and the resulting child, Hugo, is indeed born with superhuman abilities. Told not to use them, every time he inadvertently reveals his abilities, things end in disaster. He accidentally kills a high school football player during a game, and loses his bank job after rescuing a man trapped in the vault by tearing the vault door off its hinges. Hugo becomes alienated and despondent, a complete outsider in a world where he doesn’t belong who has no idea what to do with himself. By the novel’s end, Hugo ascends to the top of a mountain in a raging storm to ask God to give him some direction, some purpose in life where his powers might be useful, only to be struck dead by a bolt of lightning.

Of the seventy books Philip Wylie published in his lifetime, Gladiator remains one of only half a dozen or so still in print today. Although it contains no tights, no capes, and no arch-villains, it’s repeatedly been cited as the primary inspiration for the Superman comics, which first premiered eight years after Gladiator’s publication. But the more interesting resemblance is what the story of Hugo’s struggle to find his place in the world has to say about the author himself.

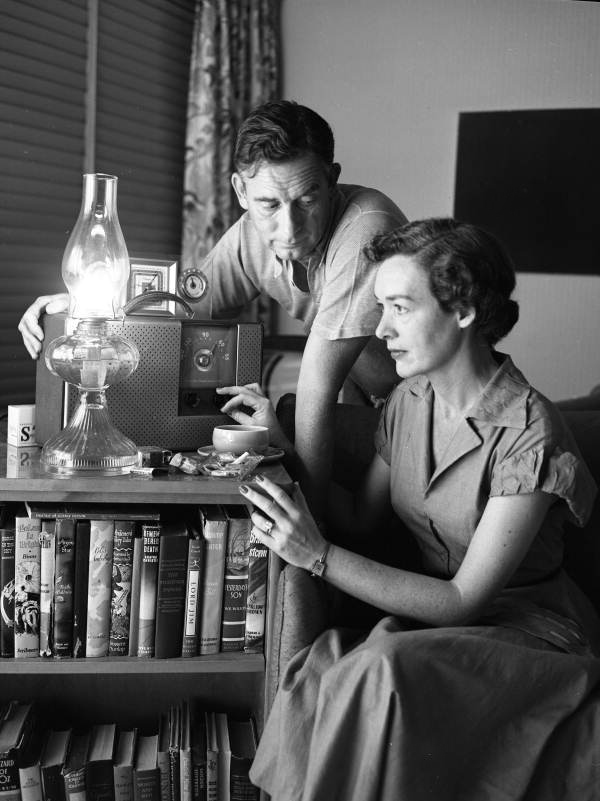

From the late twenties through the early seventies, Wylie was ubiquitous. He wrote science fiction, mysteries, satires, and social commentary. He wrote for Hollywood, academic journals, The Saturday Evening Post, and Popular Mechanics. He wrote about free speech, UFOs, foreign policy, growing orchids, and deep sea fishing. He was a newspaper columnist and a talk show regular. He was the director of an oceanographic institute and an advisor to an early incarnation of the Atomic Energy Commission.

Wylie was a polymath, adept at engineering, physics, history, sociology, psychology, anthropology, and political theory, all of which he put on display in his work. He was often ten minutes ahead of his time: pushing for civil defense preparedness a decade before duck-and-cover drills and backyard fallout shelters became commonplace. He argued that women should be given equal rights in the workplace. In his 1945 short story “The Paradise Crater,” Nazi scientists use a Uranium isotope to build an atomic bomb. The story earned Wylie six months under federal house arrest, given that with The Manhattan Project still underway, no one was supposed to know about Uranium isotopes or atomic bombs yet. He spent the last decade of his life warning against the inevitability of man-made environmental collapse.

Wylie also adamantly refused to allow himself to be labeled. In 1948 he wrote, “I am not a Protestant, or a Catholic, or a Jew; I don’t belong to any church or union. I am not and never have been a communist, fascist, leftist, liberal, tory, or rightist.”

He said this in the midst of a decidedly Christian nation getting down to the serious business of waging a holy war against communism. Wylie thumbed his nose at the whole show, stating proudly he didn’t give a good goddamn about trivialities like “God” and “State.” Despite all his lighthearted, family-friendly (and extremely popular) writing about gardening and fishing, with this blunt statement of non-conformity, he declared himself an outsider and quite intentionally put the screws to a culture obsessed with the necessity of confining and controlling things, particularly people, with clear labels.

Wylie’s pulp novels of the late twenties and early thirties often featured precursors to modern day superheroes—Nietzschean individuals with superior abilities who are more often than not destroyed by a civilization incapable of understanding them, or in Hugo’s case, by God himself. Those rare individuals with superior intelligence or physical prowess were doomed outsiders as a result. Being in his mid-twenties at the time and undeniably brilliant, it’s easy to wonder whether Wylie, consumed with youthful hubris, didn’t see himself in the same light.

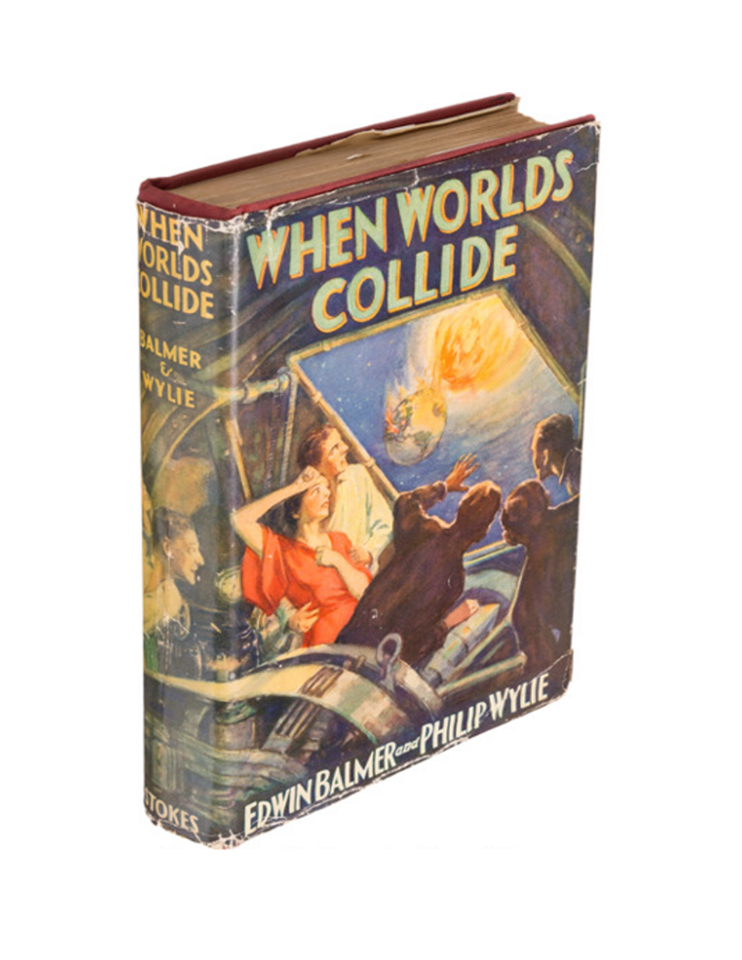

In 1933’s When Worlds Collide, co-authored with Edwin Balmer, in which a fast-approaching rogue star has marked Earth for complete annihilation, there came a shift. Instead of a superior individual trapped in a world in which he does not belong, Wylie’s superior individual concentrates on devising a means of escape for himself and a small handful of carefully chosen (and equally superior) individuals—the future of a better species—while giving nary a thought to the billions of common, unremarkable humans left behind to face certain death.

It’s not that uncommon a move—a young, extremely intelligent outsider turning his alienation on its head, forging it into a cynical wrath aimed at the masses he considers incapable of understanding him. Unlike his protagonist Hugo, being a complete outsider became for Wylie a point of pride.

In the years that followed, and to the very end, much of Wylie’s fiction concentrated on global disasters—often sparked by human folly—resulting in the loss of millions. As a public figure, Wylie himself became a savage iconoclast who seemed to take no small joy from pissing off the masses.

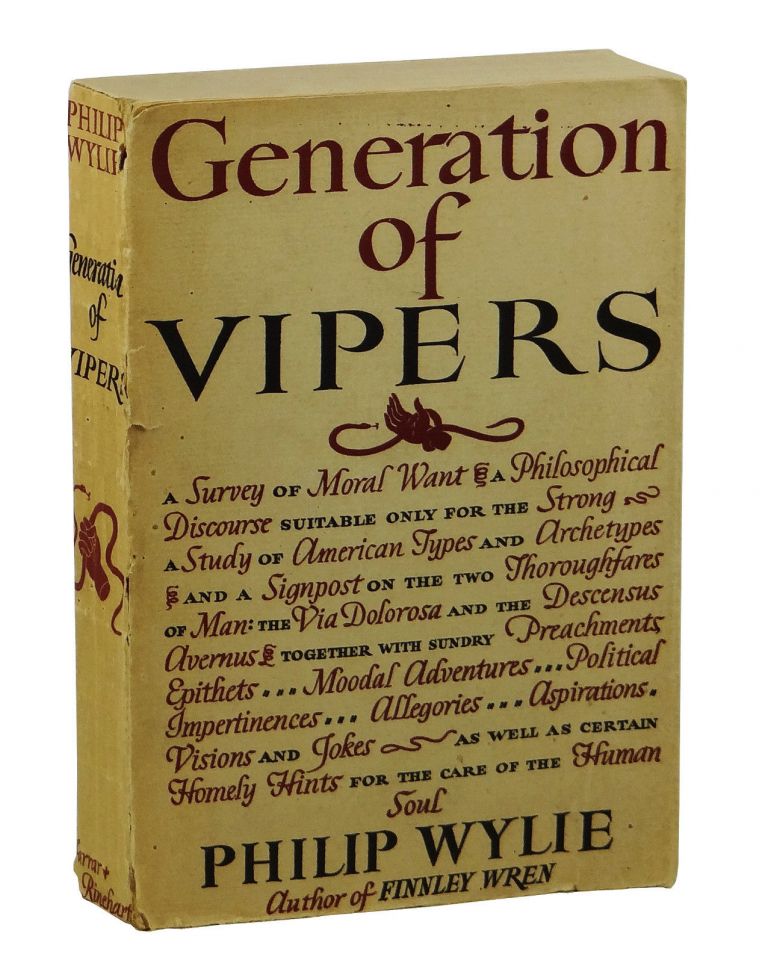

To quote a 1957 television interview with Mike Wallace, Wylie’s social criticism “violated taboos by attacking American moral values, Christianity, Doctors, Teachers, and Statesmen, to name just a few.” A number of those attacks can be found especially among the far-reaching essays collected in his 1942 anthology Generation of Vipers.

Apart from When Worlds Collide, Generation of Vipers was the first of Wylie’s books I encountered. I found a first edition selling for cheap at Gotham Book Mart and was intrigued by the title, so picked it up. It was astonishing, not only for the savagery of the prose—which foreshadowed Hunter Thompson—but also his range of targets. How he could publish wicked attacks on American morality, religion, and politics in those early gung-ho years of WWII without being charged with treason is nothing short of amazing. More amazing still, he was skewering the myth of Eisenhower’s America a decade before Eisenhower’s America existed. The book’s initial print run of four thousand copies sold out in less than a week.

Of all the attacks aimed at a fistful of sacred cows, none was more inflammatory, none raised more of a shrill public shit-storm than his attack on what he called “Momism.” To quote a brief passage:

“Men live for her, and die for her, dote upon her, and whisper her name as they pass away. In a thousand of her, there is not enough sex appeal to budge a hermit ten paces off a rock ledge. She plays bridge with the stupid veracity of a hammerhead shark. She couldn’t pass the final examinations of a fifth grader.”

Fifteen years after its original publication, Wylie was still getting death threats for that essay, and fifteen years later he was still attacking the myth of Eisenhower’s America, by name this time, writing “we have gradually become a nation of exalted ignoramuses.” That same year, 1957, he had also just published a screed against Christianity (and organized religion as a whole), The Innocent Ambassadors.

At the end of the Wallace interview, when asked if there was anyone he actually admired at the time, he cited a then little-known politician from Massachussetts named John Kennedy.

In between Wylie’s brutal public attacks on an American hypocrisy and stupidity that would one day, he was convinced, bring about the end of the world, Wylie had few qualms about taking a shamelessly populist turn now and again. At the same time that he was taking a chainsaw to suburban dreams and darkly predicting the coming war in Southeast Asia, he was whipping out cheap murder mysteries and sci-fi, and his light and frothy “Crunch and Des” stories, about the adventures of a Florida-based charter fisherman, were perennial bestsellers.

Apart from references to contemporary newsmakers like John Foster Dulles and Robert McNamara, the points Wylie brings up and the arguments he makes in his social criticism remain remarkably timely. So how is it that a figure who was everywhere for four decades—on the bestseller lists and in daily papers, in the movies and on television, could be so completely forgotten today?

First, not being able to affix a simple confining label to someone just seems to confuse and aggravate most people. As a result, to most minds Wylie was little more than a vapor, though sometimes an inescapable and irritating one. But there was a much more damning problem afoot.

In the sixties Wylie was still everywhere, writing bestselling mysteries and teleplays for popular television shows, releasing anthologies of his work and publishing articles about dolphin research and environmentalism. He was still in daily newspapers and offering political commentary on talk shows. In 1968, he even published a follow-up to Generation of Vipersentitled The Magic Animal, in which he decried the mechanization of man, the rule of technology, the ever-increasing pace of daily life, an education system that no longer had anything to do with enlightenment, and, well, everything else.

The world had caught up with Wylie before anyone noticed he had predicted all these things a long time ago. All the radical attacks he’d launched against the American status quo in Vipers the sixties counterculture had already accepted as given, and turned them into protest chants. Of course the government was a corrupt sham, religion was a cheap and ugly ruse, and even Mom was not to be trusted. By the time The Magic Animal came out, Wylie’s attacks were commonplace, the new mainstream status quo. And on top of that, his essays really can be shrill and self-righteous.

Wylie quickly began to vanish from the public consciousness. He was just another chest-thumping crank and plenty of others like Gore Vidal and William Buckley had come along to fill the role he once held.

The End of the Dream, published shortly after his death in 1972, was a bit of speculative fiction set in 2023, detailing the near obliteration of mankind following complete environmental collapse. Read the news today, over forty-five years later, and the novel remains a frighteningly prescient work. Almost completely ignored at the time, it was lost in the deluge of other eco-disaster books, films, and articles saying essentially the same thing.

With the possible exceptions of When Worlds Collide (thanks more to the movie than the book), Gladiator (at least among comic book geeks) and, just maybe, Generation of Vipers, it’s almost as if Wylie never existed. There had been a time, though—decades, even—when he’d been at the top of that same mountain Hugo had climbed, buffeted by wind and rain as he ranted at the heavens. For all his prescience, for all his ubiquity, for all his rage at the world as it was and would become, it was almost as if he’d been struck down and all memory of him erased by an angry god.