“The first time I saw her, she was naked and sixteen,” goes the first line of a failed novel I wrote about Britney Spears between 2014 and 2016. Of course, she wasn’t sixteen then. She wasn’t naked, either.

Or not exactly her, at all—there were so many of blonde girls in those years, 1999, 2000, 2001, it’s hard to remember. The phenomenon continued in 2006, 2007, 2008, the era I was trying to portray—there were so many of them, these blonde girls. Our televisions were clogged with blonde girls, our radios, our blogs. I watched them sing, I watched them dance—I’d watch, entranced, as they moved their way through elaborately choreographed routine after elaborately choreographed routine, and I had to wonder if they knew what they were doing—if they were knew what they were singing—if they understood what was implied when a teenage girl in a crop top sighed and fluttered out “oh, baby.” Did I understand? I was younger than them. I watched them, sometimes I danced along.

We grew older, and I watched as these girls, with names like Jessica, Christina, Mandy, and, yes, Britney—they were always understood to be girls; most were white and young and blonde—were primped and waxed and fashioned into something entirely bizarre. They were a record industry’s idea of what a teenage girl should look like, sound like, and the contradictions bled into their songs. They were irresistible, they sang; they were dirty, they liked candy. They were made out to be virgins, the lot of them, though at the time I wasn’t exactly sure what that meant. When they spoke of themselves or their careers, they’d use phrases like “my story’ or “God’s plan,” as though their wants and desires were mysteries even to themselves.

The breakdowns came later. One by one, they’d “go crazy,” as we at the time referred to these periods of intense and sudden self-realization, and now there was a new type of photo that we clicked on, so different from the glossy magazine shoots of old. I was a teenager by this point, and late at night I’d scroll through gossip blogs with names like Pink Is the New Blog and Oh No They Didn’t and I’d eagerly take them in, all the paparazzi photographs, I was embarrassed that I even cared—but I could not stop looking. They repelled me as much as they fascinated, these photos and their subjects, this version of femininity and adulthood and sex and danger, and even when they fell down drunk and exposed themselves and wept in public the photos were still taken. Even when they were condemned, criticized in the news as all that was wrong in Bush-era America. No matter what they did, the paparazzi were always there.

“A photograph is a secret about a secret,” the photographer Diane Arbus famously observed years earlier. “The more it tells you, the less you know.” Perched at my computer in 2007, clicking the photos of Britney shaving her head or Lindsay wielding a knife, I was so sure I knew exactly I was looking at. I was so smug, that these sentences could have been adjusted: A photo is a secret about a secret. The more you tell it, the less it shows.

The first paparazzi photograph, posits a 2019 Town & Country article, comes from 1879 or 1881, and depicts the Austro-Hungarian Empress Elisabeth, popularly known as Sisi. Famed for her beauty, in the photo she is a remote presence, perched high on a horse and hiding her face behind a fan. She does not want to be looked at. Even in this photograph she is a mystery, the very picture of imperial authority.

What is it that motivates us to try and capture fame, even—especially—when the subject is unwilling? So much has been written on the subject of photography, and yet in the twenty-first century it is the paparazzi photograph, specifically, that has become the true medium of our age. It papers our world, from high to low culture: the popular Twitter account Tabloid Art History paired, from 2016 to 2019, paparazzi photographs alongside famous works of Western art. They are a useful tool, in the guise of clickthrough galleries, for magazines otherwise devastated by social media’s lack of advertising dollars, to garner clicks. An entire cottage industry of pop songs in the early 2000s name checks them, from Britney Spears’s “Piece of Me” to Lady Gaga’s “Paparazzi” to Jay-Z and Kanye West’s “Otis,” and more. And while the paparazzi themselves have long been derided as a menace, as faceless monsters, as unprofessional amateurs, and as completely lacking in any sense of aestheticism or artistry, most contemporary paparazzi photographs are, as the academic Vanessa Díaz points out in her 2020 book Manufacturing Celebrity: Latino Paparazzi and Women Reporters in Hollywood, predominately Latino, working-class, and from immigrant backgrounds, and each one of them “major cultural producers who created some of the most circulated and iconic images of the twenty-first century.”

There is a glamour implicit in the paparazzi photograph, be it the stolen glamour that comes from simply capturing the face of a famous person or the glamour embedded in the act of photography itself. “When we are nostalgic, we take pictures,” Susan Sontag points out in On Photography. “Photography is an elegiac art, a twilight art… All photographs are memento mori.” And the rise of twenty-first century paparazzi photography coincides with an American cultural industry that is becoming less sure of itself, vulnerable to streaming and downloading, and stuck in a disappointing age of blockbusters, in which budgets and creatively promising directors are subsumed into the profitable and shallow bloat of superhero movies. The paparazzi photograph, with its whiff of trespass, hearkens back to an era in which the star was still imbued with a sense of mystery. Even when the celebrity rags insist that “stars—they’re just like us!”, the paparazzi photos they use to illustrate this prove that it isn’t true—they are, almost always, more beautiful.

The word “paparazzi” is itself glamorous, with its Italian cadence and the explosion of zs. It comes from Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and the character Paparazzo, a news photographer. Anita Ekberg, the film’s star, would in 1960 be photographed aiming a bow and arrow at a crowd of paparazzi after they had followed her home, clamoring for a photograph.

The art world would in turn become interested in the relationship between celebrity, image, consumerism, and mass media—one of Warhol’s last photos before his death, 1986’s “Paparazzi (Maria Shriver and Arnold Schwarzenegger),” photographs the crowds of photographers waiting for the famous couple.

In previous eras, of course, there had been others who had photographed themselves obsessively, whose own fame and notoriety and eventual place in history stemmed from that fact. “She looks at us,” writes Nathalie Léger of the Countess of Castiglione, one of the nineteenth century’s most photographed women, “a woman leans into the depths of her own image, simultaneously offering herself to the mirror and to the lens.” But in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the subject for this kind of photography no longer needs to be an aristocrat—just famous, the royalty of our times.

“We serialize Britney Spears. She’s our President Bush,” Harvey Levin, the founder of TMZ, told Rolling Stone in 2008, at the height of Spears’s breakdown. In the intervening years since those nights in which I stayed up late watching Spears attack a photographer with an umbrella, shave her head in front of the cameras, and lock herself and one of her children inside a bathroom during an evening that the gossip community Oh No They Didn’t termed, cruelly, “Hostage Brituation,” I have realized that part of what so fascinated me about Spears’s breakdown was the way in which it coincided with the collective insanity that was America during the Bush years. It was a time of heightened contradictions, in which female purity was fetishized alongside a pornographic sense of aesthetics, and the public was told by the president to “go shopping for their families” as a way of healing after 9/11. It was a moment of extraordinary homophobia and suspicion towards anything deemed different, a cultural push towards evangelical Christianity, and an era of warmongering and the curtailment of civil liberties that seemed to bother very few. What a perfect symbol Spears was, in a country soon to be marred by the financial crisis—a maenad wandering aimlessly through an L.A. Target, fantastically inconsistent as she rampaged in public, speaking in a faux British accent to the Hydra-headed herd of paparazzi as they followed her deep into the night.

It was an era of night, of night-vision video and nightclubbing, because at night you can do what you cannot during the day, at night you can admit your true desires. Reality and fiction were beginning to collide in new and interesting ways, from the reality television shows that flooded our screens to the growing public interest in memoir (from between 2004 to 2008, according to the Nielsan Book Scan, sales of memoirs in the U.S. increased by more than 400 percent). The Internet, too, was transforming, no longer a place where you should never reveal your true name. There were blogs of all varieties, covering music, motherhood, fashion, and so much more—like the party photo blogs, a crude imitation of paparazzi photography for a different kind of nightlife. The East Coast had Misshapes, run by two severe DJs, while the West Coast had the Cobra Snake, the Los Angeles-based photographer whose images of hipster socialites were like an inverted mirror of all that was being published on TMZ. But what kind of alternative to Hollywood were they really? Everyone looked the same, and they were all still wealthy, just in slightly different clothes. The trend died out quickly once smart phones developed, and suddenly anyone that owned an iPhone could become a personal paparazzo to their friends, no need to look at photo blogs filled with strangers. Suddenly, one had to be photogenic, or there would be hell to pay in the form of a friend’s unflattering Facebook album the next morning. I googled the Cobra Snake a few years ago, I can’t remember why—it turns out he went to school with that Trump adviser, Stephen Miller. Wealth has a desire to watch itself, to preen. Now there’s Instagram and Twitter. Reality as filtered though a phone.

It was a ridiculous time, a pompous time, narcissistic and with little to offer beyond a wan pastiche of the past—even the alternative, all those guitar bands, sounded like their 80s post-punk predecessors but robbed of all politics. Years later, I would encounter a Randall Jarrell essay from 1962, “A Sad Heart at the Supermarket,” that seemed to predict exactly what was happening, how mass media and the real and the unreal were all crowding out each other; this was my Facebook feed. “Our age is an age of nonfiction,” he wrote in a passage I have underlined and written out repeatedly in the intervening years, a passage that was to be the epigraph to my failed novel; “of gossip columns, interviews, photographic essays, documentaries; of articles, condensed or book-length, spoken or written; of real facts about real people.

Art lies to tell us the (sometimes disquieting) truth; the Medium tells us truth, facts, in order to make us believe some reassuring or entertaining lie or half-truth. These actually existing celebrities, of universally admitted importance, about whom we are told directly authoritative facts—how can fictional characters compete with them?

I wasn’t disillusioned with fiction. It felt, perhaps, that some of my peers might be—instead of novels, suddenly every young writer I knew was dreaming about writing an essay collection, something gimlet-eyed and evocative, even provocative, and yet still marketable—but as we moved further into the 2010s, as we entered 2016 and its aftermath, the distinction between the two seemed sharper, and more important, than ever before.

Now, in the 2020s, it has become fashionable to cast regrets on the early 2000s, their cruelty and their excess. The New York Times’s 2021 documentary on Spears’ breakdown and the subsequent #FreeBritney movement that has sprung up in the wake of her conservatorship portrays it as a kind of collective tragedy to be gawked at, a mass rubbernecking that brings to mind Barthes’s 1977 observation that his interest in photography is “tinged with necrophilia.” Spears’s ongoing legal battle against the restrictions of her conservatorship and her father, Jamie Spears, resulted most recently in a June 2021 testimony that included a number of shocking allegations, including the forced insertion of an IUD to prevent Spears from taking time off from her touring schedule in order to have a baby. But this is the tragedy of Britney Spears: sooner or later, the conversation always cycles back to her body. “I was in denial,” she claimed in her testimony concerning Instagram posts she had shared in the last year stating that she was okay. For Spears, who has always had a uniquely extreme relationship with the paparazzi—including even going so far as to date one, a man named Adnan Ghalib, at the height of her breakdown—the photographic surveillance of the paparazzi lens has turned into a self-surveillance mediated on social media. She is most familiar—to herself and to her audience—through the lens of a camera. The lens of the paparazzi. There will always be those photos of her from 2007, a symbol of who, in the U.S., at least, is looked at. And who does the looking.

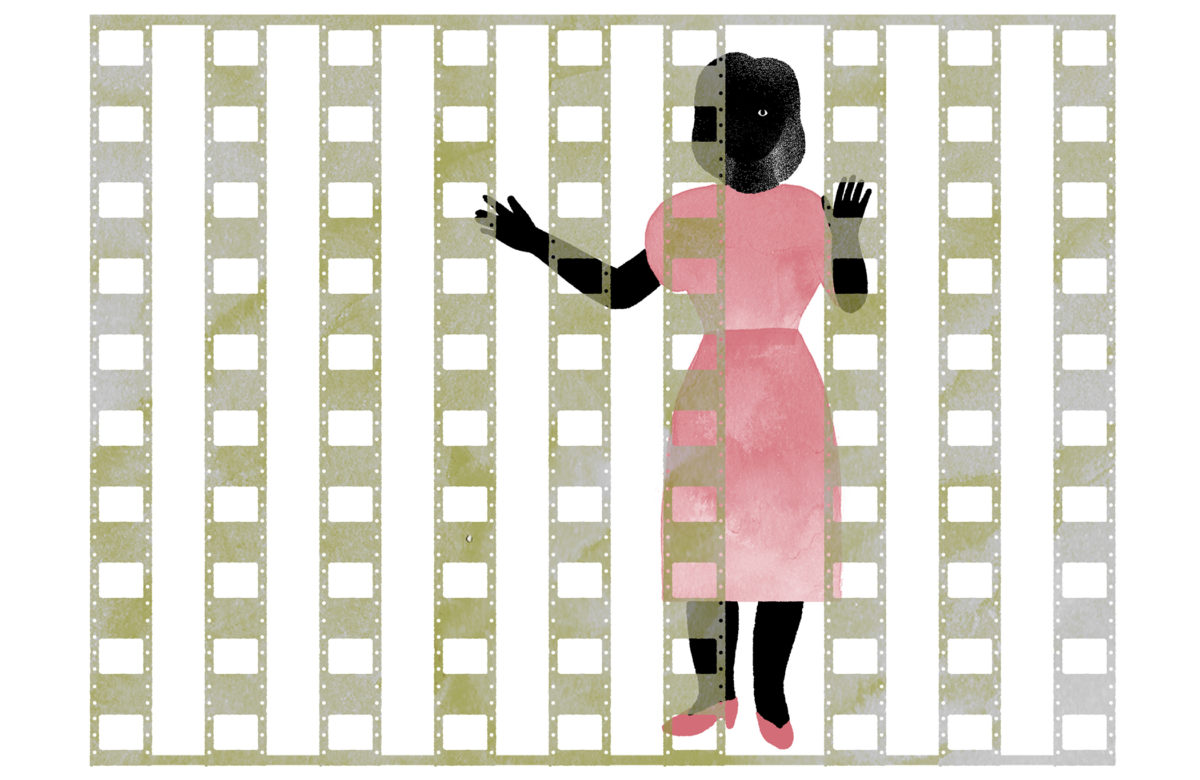

“Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality,” Sontag observed. “One can’t possess reality, one can possess (and be possessed by) images.”

In my apartment one evening in the late 2010s, I take secret photos of my friends. I take them when they do not notice, I take them on the sly, moving my phone vertically as though I am reading a text. Silently I upload these photos and tag them, and when my friends hear that soft ping, the notification, they laugh, surprised—“When did you take that?” they demand. “We’ve got a real paparazzi over here.”

The photos and what really happened are blurring, the story and the real facts about real people have never been so intertwined. This breakdown between fact and fiction is why my novel failed. The story and the headlines were too close—how can a fictional character compete with the real thing? They canceled each other out, the blonde girls in the book and the blonde girls in the photos. The women they aged into. And that is another fact that doesn’t match up with the fantasy of Britney Spears—she was never supposed to get older. The America in which she became famous was never supposed to fade.

“I don’t want anybody touching me,” she is reported to have said in 2007, just before she was pictured shaving her head. As a teenage girl, these words inflamed me. They contained an attitude, a fury, that I also wanted to brandish against a world that was starting to notice that I had a body. Who really was this woman who I had grown up viewing as a kind of cultural wallpaper, ever-present and always smiling? Her anger intoxicated me. “I’m tired of everybody touching me.” But what about being looked at?

For the rest of the evening, I turn off my phone. I am tired of an online-filtered construction of reality, every pose and caption posted to social media a too self-aware imitation of the real thing, a calculated edit of day-to-day life. Algorithms instead of fate. The internet is good at creating illusions. The possession of images. I don’t want anything that has to claim it’s based on a true story to get anyone to care, I just want the story itself. The internet is plastered with images of women. An experiment in hiding my face.