Amy Kurzweil has a classic—and enviable—cartoonist mind, equipped for creating satisfying and often funny narratives to single-panel gags as well as book-length graphic stories. Here, she talks about “The Telephone Museum,” the first installment in her illustrated “Technofeelia” series, in which she visits a treasury of antiquated communication devices.

—Kristen Radtke

THE BELIEVER: How did this comic start?

AMY KURZWEIL: I had the idea for “Technofeelia” because I’ve always been curious about human interaction with technology. What do new ways of moving, communicating, remembering, loving, and learning mean to us emotionally? What are the hypocrisies in the feelings we profess to have about new machines? And how does technology change our experiences privately or communally?

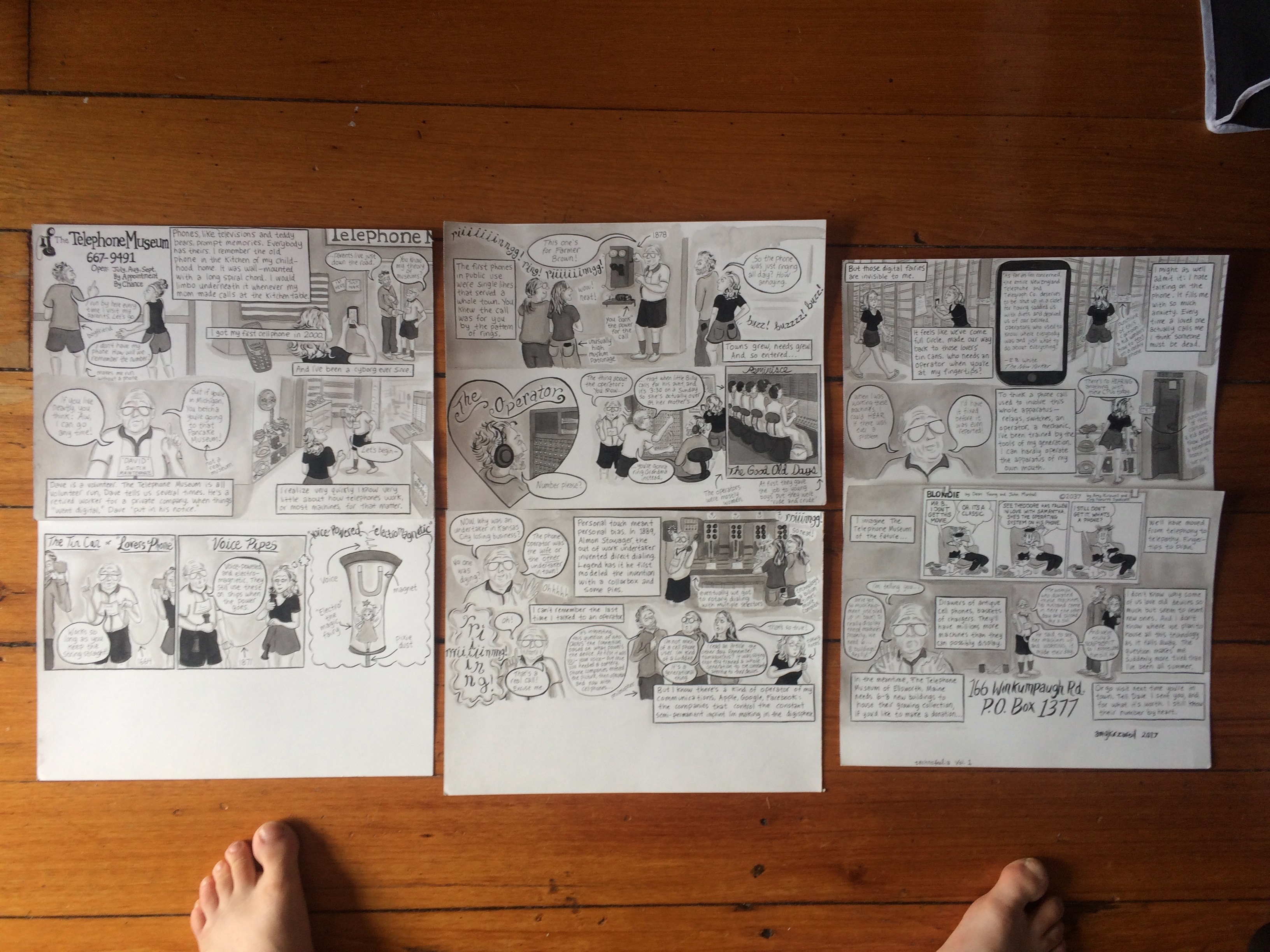

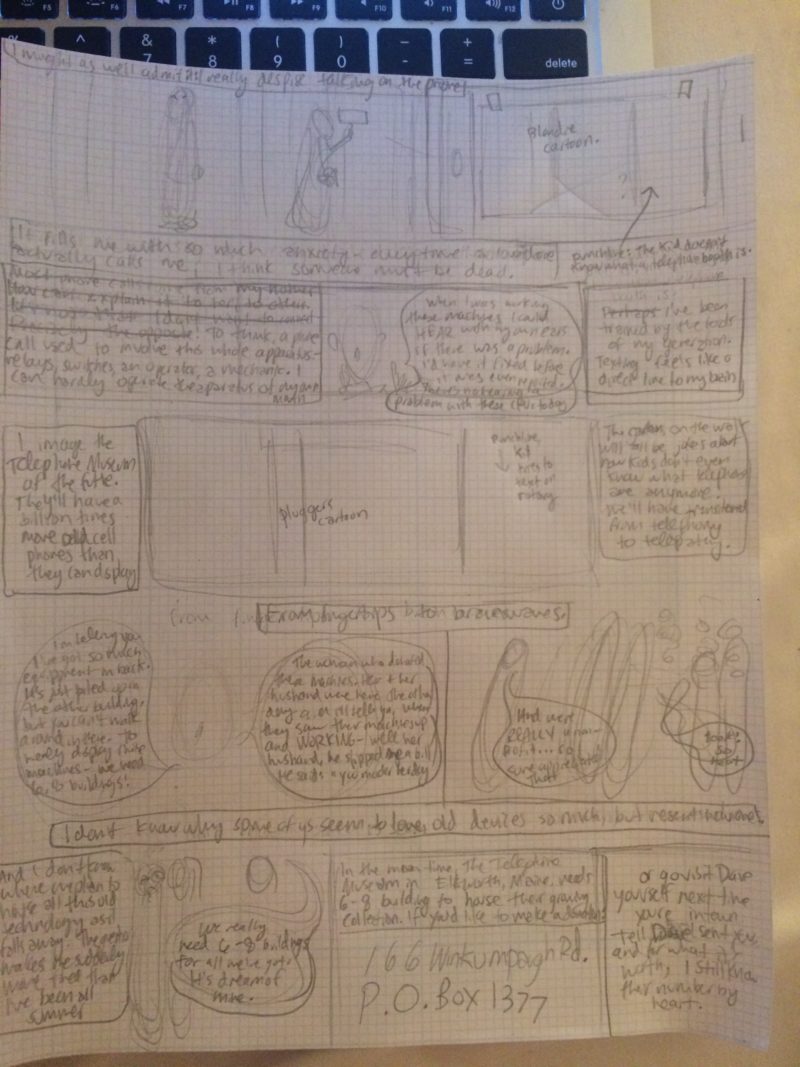

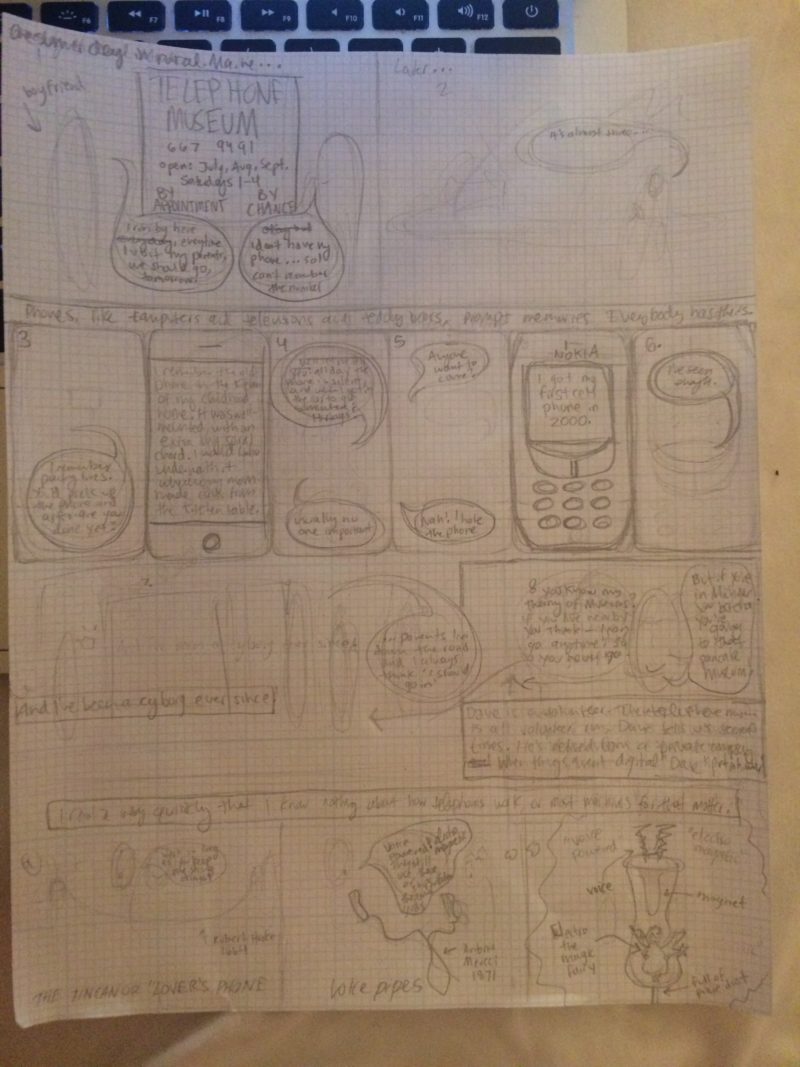

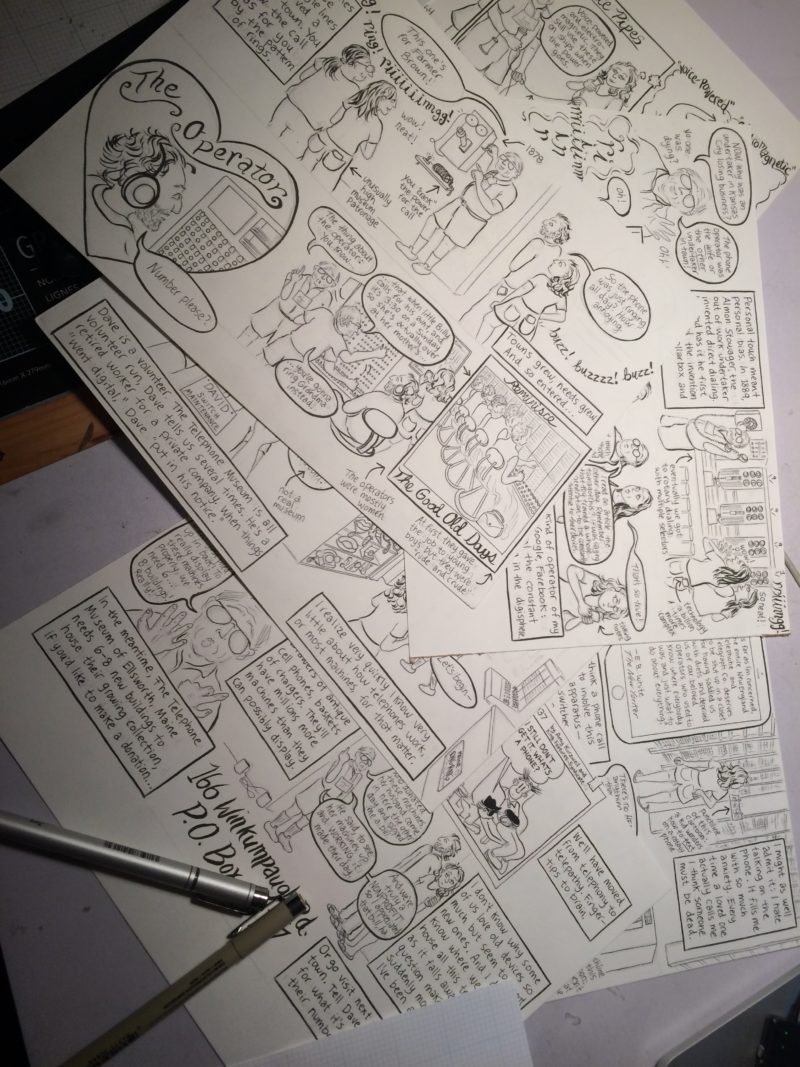

The first two installments of this series both feature trips to museums. In Vol. 1, “The Telephone Museum,” I visit a delightful Telephone Museum run out of a barn in Elsworth, ME, near where my boyfriend’s parents live, lovingly kept open by a retired telephone worker and a small rotation of volunteers. When I ran past the sign, which boasts that museum visits can be scheduled by appointment (the phone number is listed without an area code) or “by chance” I was moved. I’m compelled by tech nostalgia. The word “technology” summons visions of new revolutionary inventions in the present or the future—I think some people are inherently threatened by the word, how it gestures at irreparable change—but when I encounter old machines I’m struck with a dizzying sense of perspective. I like to imagine the world before the machines I take for granted were ubiquitous, and I want to challenge the impulse to romanticize this vision of a “simpler” time.

In Vol. 2, “Crossing Over,” I visit the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Manhattan to see a new exhibit of interactive holograms of Holocaust survivors; the avatars “hear” your questions and respond with their stories. I was especially interested in this exhibit because my first book, Flying Couch, tells my maternal grandmother’s survivor story. I’m intimately familiar with her history, and with stories like hers, and it’s fascinating to consider a world in which she might be “around” to tell her story for herself. I wonder if this technology will become, like the telephone, ubiquitous, and if this is, in some sense, one of many ways technology will continue to revise the meaning of death.

BLVR: What’s your process like?

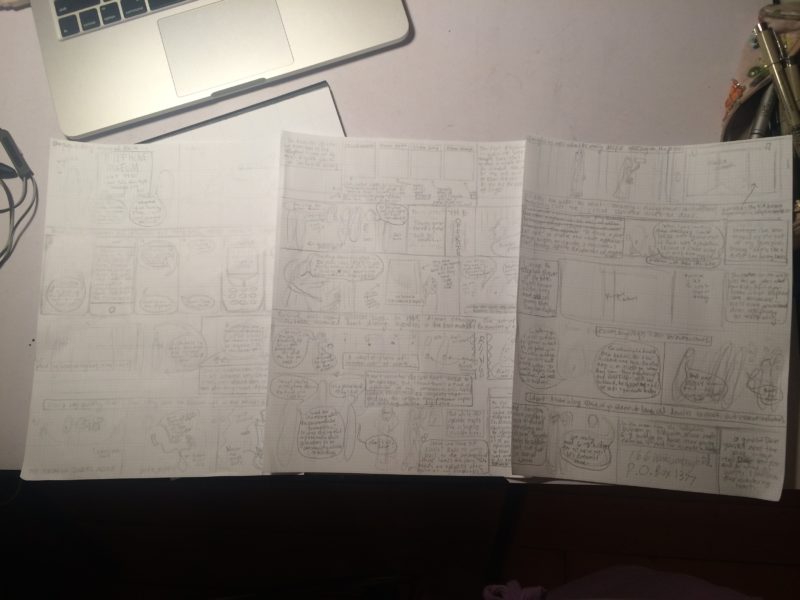

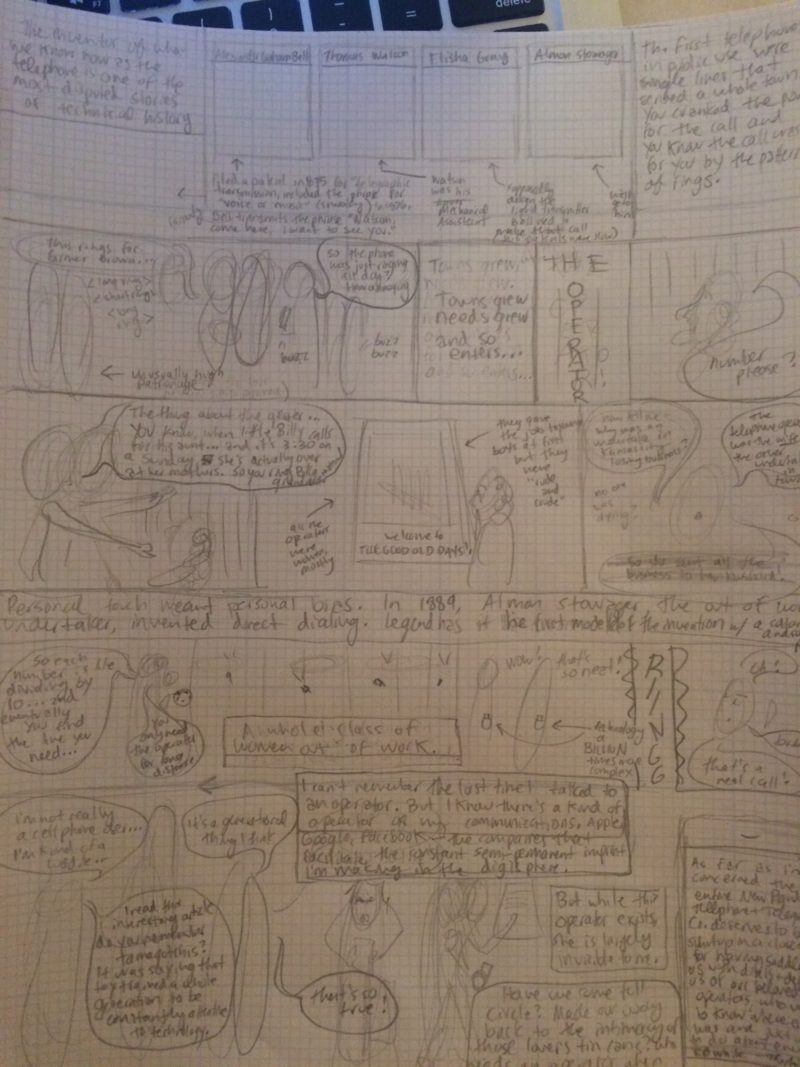

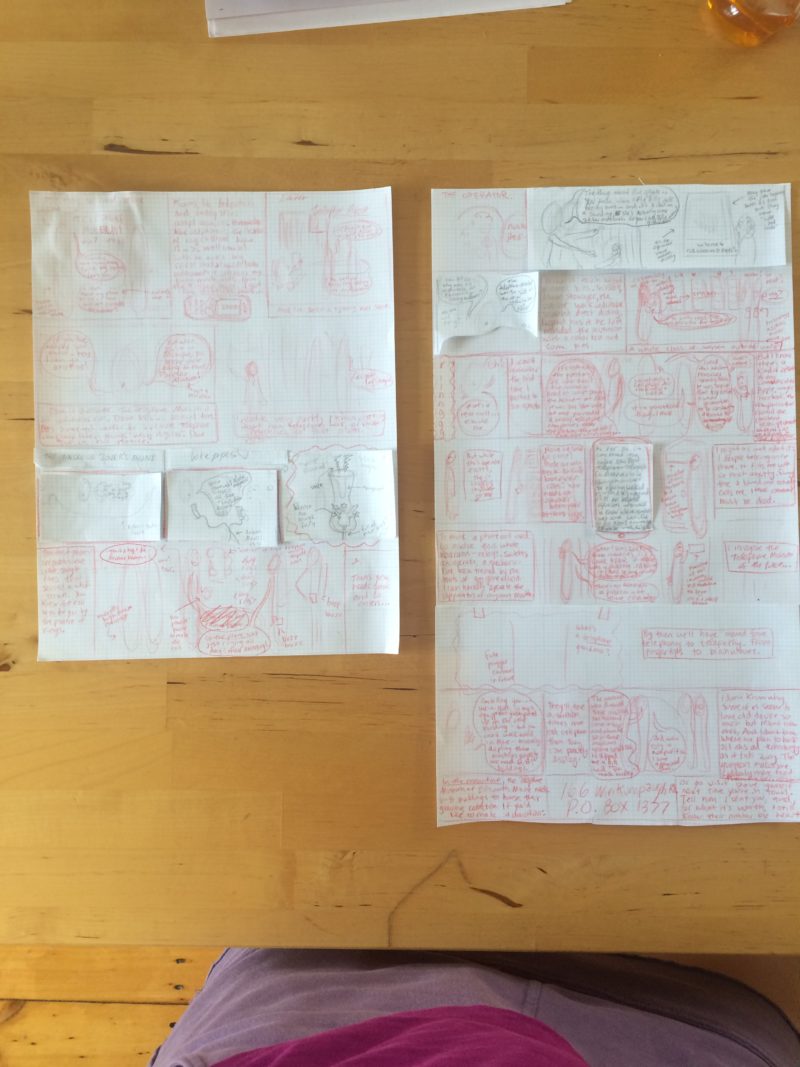

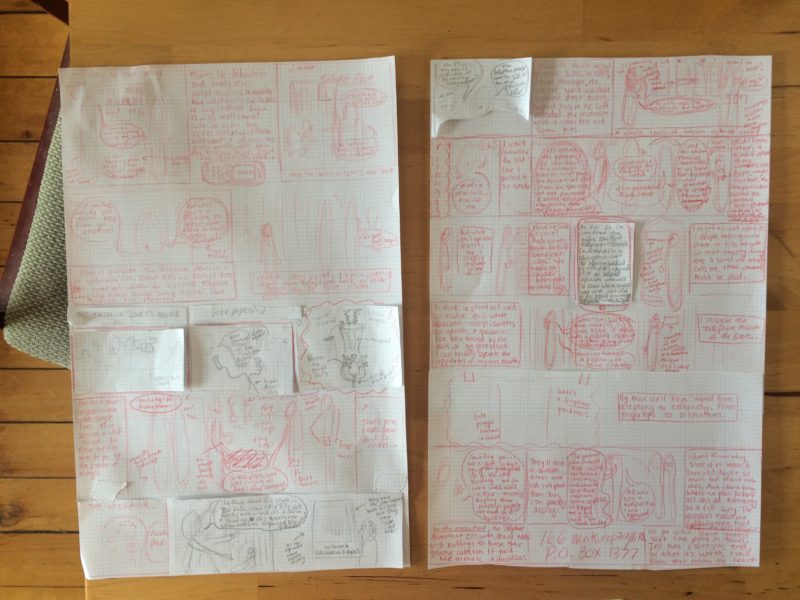

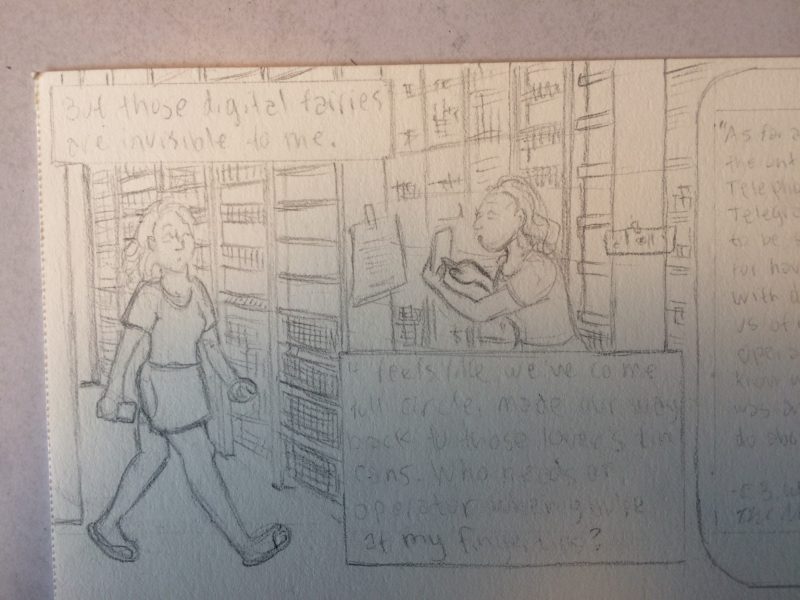

AK: My process for this series involves, first, having an experience. I go somewhere to see something specific and I take copious notes, usually in my iPhone, and I take photos and videos, too. Having an experience I know I’m going to write about makes me feel especially alive in that experience, and also surreally removed. It’s cool. Over the next several days or weeks, I write a script. Then I draft the comic roughly on graph paper and rework (sometimes this involves literally cutting and pasting with scissors and tape) until I’m satisfied with the draft, then I transfer to vellum paper, with the help of a light box and a triangle ruler. I pencil, then ink, then erase the pencil and add a wash with watered-down ink. Finally, I scan and edit in Photoshop.

BLVR: Was any aspect of making this work particularly challenging?

AK: For “Crossing Over,” I did find it difficult to have go to the Museum of Jewish Heritage and confront more stories about Holocaust. I’ve done a lot of this already, of course. I don’t think writing a book about the Holocaust has made this history easier to bear. It may have had the opposite effect on me. (You’ll see me reflect on various incarnations of this feeling in the piece.) But I was happy to discover that this exhibit was actually uplifting. I suspected it might be, which is why I wanted to see it.

BLVR: What drives you to create new work?

AK: I’m compelled to write because I want to answer certain questions, mostly: what makes us who we are? And also: how does some complicated, seemingly-contradictory thing work? This is probably why I write so often about my family.

BLVR: Without naming any comics artists, what influences you most?

AK: I think my comic style is a combination of obscure philosophy, like the books in the stacks of the library near where you made out with your college boyfriend, literary prose memoir (Joan Didion, Marry Karr etc.), underground comics from the 70s—especially the few written by women—and, uh, old-school Mickey Mouse cartoons? And then maybe mix that all up with a Chagall painting, an annotated Subway map, an anxious teenage girl’s diary, and the interactive section of the Newspaper “Funnies”… is this making people want to read my work?

BLVR: Which comic should we drop everything and read right now?

AK: That’s hard, but I’ll go with my latest obsession The Arab of the Future. There are at least three volumes and growing, so you need to catch up! This memoir series is a good way to learn something nuanced about life in the middle east, while occasionally laughing.

BLVR: What are you working on next?

AK: I just sold my next book, another graphic memoir called Artificial. It’s the story of my father’s mission to bring his father, a classical pianist and conductor who fled Vienna in 1938, a man who died before I was born, back to life as an artificially intelligent avatar using the documents saved in a storage unit. My Technofeelia series feels like a sister project to this memoir, so I’m grateful to have the outlet. The next volume of Technofeelia will either explore video games or sex robots. Please feel free to write me with any tips or suggestions!