I. SUNSHINE STATES

Not long ago, my mother asked me if I remembered the Coppertone billboard in Surfer’s Paradise. I didn’t. I had spent most of my childhood holidays on Gold Coast beaches with my mother. I had been rescued by lifesavers from the waves all along that stretch of southern Queensland, and learned to bodysurf, and watched my hair bleach blonde in the sun, but I had no memory of the billboard in Surfer’s Paradise.

My mother told me that the Coppertone billboard was erected in Surfer’s Paradise during the 1960s, when she was a child. Growing up on the beaches of the Gold Coast, my mother knew Surfer’s Paradise as the El Dorado for a certain kind of sunshine-seeking Australian schemer. The beachfront was built up during the 1980s when economic deregulation led to a boom in ugly skyscrapers, gold chains and perms, but in the 1960s the Gold Coast was still gorgeous.

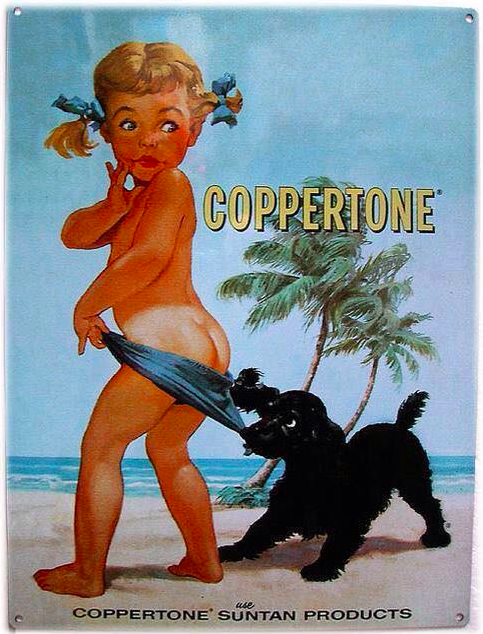

When Coppertone erected their billboard in Surfer’s Paradise, the town felt and looked liked a small-scale version of Miami, where the company had erected its original sign on Biscayne Boulevard a decade earlier. The billboard featured Little Miss Coppertone. Since 1953, she has been the international mascot for Coppertone sunscreen. She wears pigtails and navy blue bikini pants, and she is caught in a moment of perpetual surprise. She turns, looking behind her at the little black dog biting her pants and yanking them down. The yanked-down bikini pants reveal the tan line across the little girl’s back and the bright white skin on her bottom. “Don’t be a paleface,” read the type beneath the girl and the dog on the billboard in Surfer’s Paradise.

My mother told me that she had seen the Coppertone billboard again on a recent visit to Queensland. It was in the same place it had always been, on the same stretch of roadside, but there had been a change. “Now,” my mother told me, “the little girl wears a full-piece swimming costume. The dog is still pulling her pants down. But you don’t see the color shift anymore when we bites her. Because you’re not meant to get a tan anymore, and you’re not meant to show little girls’ bottoms.”

In Australia, there is a poem that everybody knows called “My Country.” Children are taught to recite the poem in school, and it has been featured in everything from anti-littering campaigns to advertisements for Tip Top bread. Written by Dorothea McKellar in 1908, most adults have retained only a few lines from the second stanza:

I love a sunburnt country

A land of sweeping plains

Of ragged mountain ranges

Of droughts and flooding rains.

The poem captures something ecologically specific about the geography of the country I was born in—its vastness, its intensity, and its potential to cause indiscriminate harm. It is not an especially good poem, but I memorized “My Country” when I was young, and often when I am drunk and happy I will recite it to utterly uninterested companions. That opening phrase—”I love a sunburnt country”—is the kind of thing that will always make me feel Australian no matter how long ago I moved away.

The southern Queensland of my mother’s childhood was the epitome of the Sunburnt Country. In the mornings of the 1960s she walked to school barefoot, carrying her sandals in her hands. Afternoons were spent in the open lots and drained mangroves of the post-war suburban development my grandparents had chosen when they’d moved the family north from Sydney in 1965. Weekends were spent on the beaches. My mother’s memories are filled with the smell of suntan oil and hot chips, with seagulls and bluebottle jellyfish washed up on the shoreline. Afternoons brought the flush, then the sting, then the application of calamine lotion across burnt shoulders.

The logic was this: you should burn early in the summer if you were going to burn at all. That way, you would only endure the sting and the peeling for a couple of days. A week later the burnt skin peeled off, and the body would emerge golden from its snakeskin. For the rest of the summer the suntan would deepen. You would lie on the sand, empty headed and sweaty and warm, inviting the sun to penetrate your body and lodge deep inside you where it nested, waiting.

When my mother was in high school her parents left Queensland and moved the family south to Sydney. There, my mother and her friends would rub baby oil into their limbs and lay under the sun during lunchtimes. Her friends in Sydney were all children of Greek, Italian and Croatian immigrants. Their skin tanned golden brown. But my mother has curly red hair and “cheap Irish skin,” and the thing she called a tan was always more of a burn that blurred the freckles together.

I didn’t inherit my mother’s “cheap, Irish skin.” I had my father’s skin; pale but free of freckles. As a child, I would tan to a solid gold. “A lovely color,” my grandparents would observe when I wandered inside from their backyard, because to my grandparents, like many Anglo-Australians who had lived through the twentieth century, it was considered healthy to be golden. The nation’s wealth, after all, was built on gold. Gold was the color of the sand on our beaches. Gold was the color of the sugar and the wheat that we farmed on the plains. Gold was the color of the sun that beat down relentlessly through the mild winters and fierce summers. The country’s official national colors were changed in the 1980s, a decade before my birth, from the blue, white and red of the Union Jack, to green and gold, the colors of the landscape.

It was around the time that the national colors changed in the 1980s that my grandfather’s legs took on the crumbling quality of a paperbark tree. It was in the 1980s that my mother first needed to consult a dermatologist for suspect marks on her arms and legs. It was in the 1980s that the ABC News reported a tear in the ozone layer over the South Pole, not far from Australian shores.

Australia has the second highest rate of skin cancer in the world. Narrowly eclipsed by New Zealand, both countries lie closer to the tear in the ozone layer than any other. Around the time that the hole was discovered in 1985, doctors noted a spike in skin cancer diagnoses. From 1982 to 2016 the number of melanomas diagnosed in Australia increased from 3,526 to an estimated 13,280. The rise has been attributed to a combination of three factors—an aging population, the popularity of “sun-seeking” behavior in my grandparents’ and parents’ generation, and the increase in ultraviolet (UV) radiation due to stratospheric ozone depletion.

In response to the rise in skin cancer diagnoses, the Australian Cancer Council launched Slip! Slop! Slap!, its most successful public health campaign on record. The television advertisement that debuted in 1981 featured an animated seagull named Sid. He had a lisp. He wore a t-shirt. He seemed friendly. He advised the nation to protect themselves from the sun—slip on a sun-protective t-shirt, slop on some sunscreen, and slap on a hat.

When I began primary school in the 1990s the seagull was gone but the slogan was the same. Outside my classroom there was always a picture of a nearly-melting snowman, protected from obliteration by his t-shirt, his sunscreen, and his hat. The rule was ‘No Hat, No Play.’ You had to wear a hat when you left the classroom and walked outside, ideally one with a floppy back to protect your neck. If you forgot your hat, the on-duty teacher would locate you and remove you from the playground. You would be banished to the “wet-weather shed” for the remainder of recess, a dank open-air hall that always felt more like punishment than protection. All the children shared our hats in an effort to fool the teachers, and so we all had head lice.

These public health campaigns encouraged a shift in national consciousness. It wasn’t like we saw a tan as any less desirable, but by the 1990s Australians were attuned to the violence the sun inflicted on the body. The violence was contained even in the language we used. In America, you are tan. In Australia, you are tanned. Like a piece of leather, the Australian conception of tanning is of flesh undergoing a kind of violation. It’s the difference between the neutrality of an adjective and the powerful unpredictability of the verb.

In 2007, the state of New South Wales introduced an updated campaign entitled, ‘The Dark Side of Tanning.” The television spot featured a pretty, bikini-clad girl on a beach towel. The camera zooms in on her skin, smooth and glistening with sweat. Then it dives through. “Tanning is skin cells in trauma,” the voiceover actor informs us. Beneath the surface of the skin, you watch the sunlight damage the skin cells, see the cells develop tentacles and begin to writhe, and then the cells turn black, grow, replicate, beginning to spread through the girl’s body like sticky tar. “Just one millimeter deep and it can get into your bloodstream and spread,” warns the actor. “So even if a melanoma is cut out the cancer can reappear, months or years later often in your lung, liver or brain.” The camera dives out, back to the girl on the beach with her bikini and her book. “And you haven’t even started to burn yet,” he tells us.

Recently, on the phone with my sister, she explained how it felt to walk outside during warm days in Melbourne. “It’s not like this anywhere else in the world,” she complained. “You’re outside for half an hour, and you can feel it burning you.” And it’s true. Most Australians will tell you that the sun feels different when you leave the country and travel elsewhere. You can get sunburned anywhere in the world, but not like you can in Australia. Half an hour is all it takes. It’s a missed bus, a walk to the shops, sitting in heavy traffic with the sun coming in through the windows. If you don’t have sunscreen, there’s a good chance you’ll begin to tan. If you have my mother’s skin, you burn.

In 2010, the United Nations Environment Program released its assessment of the effects of ozone depletion and climate change. They concluded that the projected changes to ozone and clouds may affect the levels of UV radiation, and that radiation is likely to be stronger in Australia and New Zealand than anywhere else on earth. Incidences of skin cancer, they expect, will rise.

Since 2000, depictions of Little Miss Coppertone have been taken down around the world, from Miami to Surfer’s Paradise. If they are replaced, the Coppertone ads feature a modern incarnation of the little girl and her dog. The new Little Miss Coppertone wears the full-piece swimsuit. She doesn’t have a tan line. You don’t see her bright, white bottom.

II. THE RUSH

In 1851 a man named Edward Hargreaves discovered a grain of gold outside the town of Orange, 160 miles west of Sydney. Recently returned from the gold fields of San Francisco, Hargreaves had been scratching around the plains for months, convinced that New South Wales looked too similar to California for there to be no gold in the soil.

Two months later there were reports of gold in Clunes and Ballarat and Bendigo. By the end of May the town of Bathurst was filled with diggers. They found it flowing from New South Wales, north to Queensland, and south into Victoria. Dreams of gold ran all up and down the Pacific coast.

Men came to mine gold from England and Ireland and Wales. From Germany and France. From China and Japan. In a few years, Melbourne transformed from a small town to the most beautiful city on the continent. The population ballooned to four times its pre-rush size. Pacific Islanders filled the sugar plantations in the north. By the 1870s there were 50,000 Asian immigrants living in Australia. Roads were paved and lawns were grown. Gardens filled with English roses were cultivated under the fierce southeastern sun.

For much of the nineteenth century, doctors weren’t at all convinced that the British subject was constitutionally suited to antipodean climates. A Scottish physician, Patrick Divorty, reported in the 1850s that the Australian climate generally lowered the tone of a European body. Fresh complexions turned sallow and harsh, rosy cheeks turned gray, skin became “shriveled and unctuous.” The men got thin and melancholy and drunk. They had a tendency to keel over in the street, or commence raving. The women got peaky and their teeth decayed. He noted a “relaxed fiber” to the Australian female, and lamentably small tits.

Doctor C. Travers Mackin joined some dots. He wondered whether the irritation of the Australian sun was conveyed through delicate white skin to the brain beneath, causing anything from confusion to vertigo, apathy, nausea and “congestive apoplexy.” The white body, they supposed, simply wasn’t up to the environment.

If the tropics of Queensland were ever to be populated, declared the imperial booster R.W. Dale, English, Scots, or Irishmen could not possibly perform the necessary labor. He concluded that those men “may find the capital, and may direct the labor; but the laborers themselves, who must form the great majority of the population, will be colored people.”

One doctor, Thomas McMillan, was convinced that only remaking the land in the British image would help adjust the British subject. He recommended the establishment of paved roads, lawns and ornamental gardens.

Upon Federation in 1901, Australia’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton, argued that “the doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman,” and that the last thing anybody wanted was for the country to develop anything similar to America’s “negro problem.” This announcement ushered in a series of laws that came to constitute the “White Australia Policy.” The White Australia Policy was designed to maintain the British character of the country. Further Asian arrivals were forbidden. Pacific Islanders were subject to mass deportations. The Immigration Restriction Act did not explicitly prohibit the immigration of people with dark skin—this would have offended British subjects in India—rather, the legislation called for a “dictation test,” to be administered in any European language of the examiners choosing. Speak fluent English, Portuguese, and Cantonese? Wonderful. You’ll be taking the test in Gaelic.

The effective ban on any further non-white immigration marked a sinister start to Australian federation. Proponents of the White Australia Policy advocated a dream of racial purity that had never existed. This dream rubbed up against the lived realities of many Australians. These were Australians who could remember a recent past that had been multi-lingual and multi-ethnic, a past that was complex, where the government insisted on simplicity. The country descended into a state of historical refusal, one that denied the indigenous ownership of the land and the institutional use of violence in the expansion of the colonial project. The history was buried in the mythology of bush nationalism, the greatest example of which was Dorothea Mackellar and her poem about her love for the sunburnt country.

Australia pushed its history down into the recesses of its psyche, and strange symptoms crept into the body politic.

III. THE BRIEF REIGN OF THE BUSH POETS

When Dorothea McKellar wrote “I love a sunburnt country,” she was nineteen years old, and living in England. Raised wealthy, Mackellar had spent parts of her childhood in rural Gunnedah on the substantial properties her family owned in and around the Hunter Valley. Explaining in later life how and why she had written the poem, Mackellar remembered that “a friend was speaking to me about England… and she was talking about Australia and what it didn’t have, compared to England. And I began talking about what it did have that England hadn’t.”

The country of Mackellar’s poem is willful and opal-hearted. It is full of cattle keeling over under pitiless skies, of white ring-barked forests, of lianas and orchids and ferns nodding under the hot gold hush of noon. It is a land of the Rainbow Gold. The word “gold” is the most frequently repeated noun in the poem, next to “land,” “heart,” and “love.”

Mackellar had been born in 1885, and “My Country,” published a few years after Federation, spoke to the blossoming of Australian nationalism. It was only in Mackellar’s era that the country’s “bush poets,” of which she was one, turned to the landscape as a cultural symbol, rhapsodizing about stockmen and shearers out on the plains. Such poems helped white Australia reconceive of the landscape as an authentic manifestation of their essential nature. In his history of convict Australia, Robert Hughes observes that “A favorite trope of journalism and verse at the time of the Australian Centennial, in 1888, was that of the nation as a young vigorous person gazing into the rising sun, turning his or her back on the dark crouching shadows of the past.”

My grandfather, speaking of his youth, frequently observed that he had lived “a South Sea Island Experience.” In early photographs, he is sitting or standing on beaches in Sydney and in Queensland, tanned a deep golden brown from the sun, strong and large muscled from the weights he used to lift.

By the early twentieth century, white Australians were no longer thought of as being constitutionally unfit for the climate. In fact, the model Australian man looked much like my grandfather—suntanned, muscular, a hard worker during his union-approved eight hours, loyal to his mates, master of his body and mind. He was a golden, “vigorous person gazing into the rising sun.”

By the time I knew him, my grandfather’s body had fallen apart. His belly spilled over the waistband of his trousers, and his eyebrows grew at ninety-degree angles from his face. I remember his legs the best. They were scabbed, carbuncled and crusted, yellow and red, thrusting out from his shorts and into the small horror of his open-toed sandals. He was nearly always bearing a Band-Aid over a place that had torn, or a spot the dermatologist had deemed suspect. I was never sure whether age did that to everybody, or whether it was just my grandfather. He supposed that it was the steroids he had been prescribed since the motorcycle accident he had had when he was seventeen. He never put it down to the “South-Sea Island Experience” of his youth.

My grandfather’s conversation was full of references to his appointments with the “Skin Doctor.” He taught me what to watch out for. To keep an eye on any crusty non-healing sores or an amorphous red or pale lump, and to pay attention to moles and freckles, any changes in their texture, thickness, or colour. Dark brown is troubling, black is bad, blue is worse.

He was a man so barnacled by solar keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas and the scars of their burning off that I was afraid to touch him. In fact, I cannot remember touching him at all until the weeks before he died in 2012. That afternoon in May I stood by the bed where my grandfather lay prostrate in a palliative care facility. I leaned down. He hugged me close and, whispering into my hair, he told me I had grown into a beautiful woman.

The skin on his arms felt like very old leather. In my arms he was breakable, a body ruined. Because in the end it didn’t matter how meticulous my grandfather was about checking his skin. An undetected melanoma went to his brain, and it killed him.

IV. THE EFFECTS OF UNREALITY

My uncle is an artist trained in Russian Orthodox iconography. He paints using gold leaf. The gold produces an effect of unreality. Instead of being absorbed by shadows and highlights, light hitting gold leaf falls across the flat surface of a canvas. It glints, but it has no depth. The image it produces is extraordinarily beautiful, but it cannot reproduce reality in the way that, as a child, I believed art was supposed to.

But I understood early on in my life that gold was valuable, even if it was reflective of dreams and illusion more than it had the capacity to represent reality. My mother wore a gold bangle around her wrist that my father had bought her when they were married. She wore small gold hoops in her ears and a gold ring on the fourth finger of her right hand. Gold was symbolic of the sun, of wealth, of the very best things and feats. That was why it felt like the highest praise every time my grandparents told me I was a lovely golden color. The best version of myself was gold.

My mother raised me on the beaches of Sydney, trying to replicate for me the childhood she had spent on the Gold Coast. The beach is the place in the world that makes me most happy. When I was small my mother would need to physically restrain me by the back of my swimming costume as I ran down the sand and towards the surf. She made me stay put on the towel as she rubbed me down with SPF 30+. She reapplied the sunscreen every two hours, like clockwork. My mother made sure I was protected, and by the time I was twelve I was convinced that the sun couldn’t burn me because it never had before.

Not long after my twelfth birthday my father drove me down to the beach house my stepmother’s parents then owned on the Mornington Peninsula. Under the care of my father, I went largely unsupervised. I read inappropriate novels, developed an unholy knot in my hair, and, too nervous to tell anybody I had my period, bled into my jeans for a week. When I was in the ocean the blood washed out of what I was wearing, and so I spent hours that week on the Mornington Peninsula standing in the water and letting the blood wash out. The days were long and gorgeous. The sun beat down and the gulls called and everything smelt of salt and sweat and seaweed. I wasn’t wearing sunscreen.

And so I burned. First came the terrible sting and throb of my arms. Soon, fabric was agony. So was the shower. In the mirror I could turn and see the length of my back and arms turning a vivid red. At night I developed a low level fever and lay awake until daybreak, lying on my stomach beneath the poor circulation of the ceiling fan. Blisters formed on my shoulders. A week later, sitting on the plane that would fly me back to Sydney, I found that I could sweep my hand along my shoulder, and the skin would come away in papery fragments and great satisfying strips. I peeled for days. The burn stripped off. And I found that the old logic held true. Beneath the burn, I was golden.

I have been sunburned more times than I can count. I have burned at music festivals and sitting in parks reading books. I burned waiting for the bus and the train. I burned on the Manly Ferry and sitting in the passenger seat of a car with the windows down. I have burned on beaches all over Australia, once in Greece, and twice in California. I have burned badly enough for the skin to peel off my shoulders, my thighs, my forearms, my chest, my feet, and my face.

According to the Australian Cancer Council, intense sun exposure—both burning and tanning—during the first three decades of your life, increases the risk of developing melanoma by one and a half times. Melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, is particularly associated with being badly burnt and suntanned between the ages of 15 and 20. Other risk factors include a family history of skin cancer, fair skin, light hair, and light eyes.

I am pale, with red hair and blue eyes. When I look in the mirror now, I don’t see the sun damage. Not yet. But I know it will come.

V. SUBTEXT AS TEXT

The Victorians held that a suntan connoted a poor character and dubious morals. A pale face signaled candor, virtue, and wealth. A lily-white face was a transparent window into a blemishless soul, pink sometimes with blush, ashen with grief, red from rage. A white face could display the full spectrum of civilized emotions.

Things changed in 1890, when Theobald A. Palm, a medical missionary, reported that overwhelming data suggested that sunlight was essential to the health of humans and animals alike. His findings were confirmed shortly thereafter by the discovery of the relationship between vitamin D and sunlight.

It was discovered that the sun was good for all sorts of things. In 1903, a Swiss physician opened the first heliotherapy clinic, treating tubercular patients with sunbaths at a high altitude. The therapeutic effects of the sun were touted around the world, and soon heliotherapy was being used to treat everything from anemia to Hodgkin’s disease, sepsis and syphilis. In the same year that the first Swiss clinic opened, Niels Finsen won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the treatment of lupus vulgaris with light radiation, establishing himself as the father of scientific phototherapy. Finsen was a booster for the sun. “All that I have accomplished in my experiments with light and all that I have learned about its therapeutic value has come because I needed the light so much myself. I long for it,” he said. Finsen encouraged humanity to take the view of themselves as creatures just as in need of the sun as other animals. “Let [the sun] break through suddenly on a cloudy day, and see the change! Insects that were drowsy wake up and take wing and lizards and snakes come out to sun themselves and the birds burst into song.”

It was a truth universally established that the sun was good for you. A healthy face was a suntanned one, and in 1929 Coco Chanel cemented the trend, commenting that, “the 1929 girl must be tanned,” because “a golden tan is the index of chic.”

Suntanning was recommended as a health aid in the lifestyle pages of Australian newspapers, even during the war. An October 11, 1941 edition of Melbourne’s Weekly Times advises starting to work on your suntan early: “There are many days now when there is sufficient warmth in the sun to make sunbathing a pleasant and healthful pastime, if you have a sheltered garden, verandah or balcony and you can spare the time from war work or other jobs… The mere fact of lying relaxed in the fresh air, with the health-giving rays of the sun playing on your body would be beneficial, apart from your main object of getting nice and brown.”

By the 1960s, the Australian Women’s Weekly was touting the slimming benefits of a suntan—“an overweight body looks less heavy when tan, and a too-thin figure seems more solid with one.” It was healthy, easy, and moreover, it was characteristically Australian: “Sunburn, peeling, and all stages of getting or losing a tan are part of your heritage.”

Charmian, the beauty adviser to the Adelaide News, recommended a gradual approach to tanning. “The first lesson in suntanning is that you must not hurry. Don’t wait until Christmas and expect to become the color of a South-Sea Islander in a week.” She advises lying in the garden for five minutes under direct sun, covered in almond oil. Move to the shade for half an hour, then back in to the sun for five minutes. She also advises vinegar. “In fact, it is a jolly good idea to carry always a small bottle of vinegar to the beach, and to dab the exposed skin before venturing on to the sands.” Although, The Evening Advocate advised in 1946, one wants to be careful not to become too suntanned: “Even cultivation of the dark mahogany shade is frowned upon by dermatologists as producing a thick, coarse appearance.” If you happened to tan to a dark mahogany shade, it was always possible to fade your suntan “back to normal.” A 1936 article in the Nambour Chronicle advised the application of sour milk before bedtime.

Charmian concludes her advice with observing, “It is a curious fact that blondes can wear a darker suntan makeup than brunettes. Nothing is more attractive than blonde hair, blue eyes, and suntan.” The threat posed to blondes was a serious topic of discussion in the women’s pages. A 1935 edition of the Northern Times advises that while a tan is fashionable, sunburn will mar even a blonde’s powers of attraction: “the poor blonde’s face becomes a deep red and the majority of brunettes turn far too deep a brown.” For this reason, a 1938 edition of Melbourne’s Table Talk advised a gradual, daily dose of the sun. “You can regulate your suntan this way. A good thing, because even the duskiest of us has no wish to appear like an aboriginal,” they observed.

So frequently, the women’s pages of Australian newspapers made the subtext text—golden skin was gold only so long as it was developed on the surface of white skin. This was skin that could fade “back to normal.” In all other cases the gold was brown, it was coarse, it was unattractive, suggestive of indigenous, Asian, or Pacific Islander heritage, all those nations who were, at the time the newspaper pieces were written, barred from setting foot on Australian shores, or their presence utterly ignored.

It has always been the case that whenever Australians recite Dorothea Mackellar’s poem, we are asserting a belief about race, because to assert that Australia is “the sunburnt country” is to assert its whiteness. Such an assertion is symptomatic of the amnesia longed for by Robert Hughes’ description of the vigorous young Australian “gazing into the rising sun, turning his or her back on the dark crouching shadows of the past.” It was an amnesia evident every time my grandparents remarked on what a lovely golden tan I had, and every time a magazine cautioned against become “too deep a brown,” tanning to a “dark mahogany shade,” or against appearing “like an aboriginal.”

VI. INFECTIONS IN THE BLOODSTREAM

Five months after that first sunburn on the Mornington Peninsula when I was twelve, my mother got sick. For the first few days, it seemed like she had the flu. But she got worse. Her fever spiked. She began to vomit. I recall watching her sitting on the edge of the bathtub in her dressing gown, so exhausted she could barely sit up, retching bile and water into the bath. After three days, we took her to the hospital. I understood by the way my stepfather drove through the empty early-morning streets that my mother might be about to die.

At first they suspected blood cancer. From the emergency room my mother was sent to the hematology ward. Noticing a heart murmur, the hematologists sent her to cardiology. In cardiology she was diagnosed with endocarditis, an infection of the lining and valves of the heart.

My mother was hospitalized for two months with an infection more commonly seen in long-term heroin addicts than forty-three year old solicitors. For the first few weeks she was barely awake. She turned yellow. She developed liver failure. Then kidney failure. She vomited every time she was administered a blood transfusion, which she needed, because her bone marrow had ceased to create enough red blood cells to keep her alive.

Eventually, the doctors discovered the antibodies causing my mother’s body to reject blood transfusions. Through a process of trial and error, they identified the specific bacterium infecting her heart. The question was how she had acquired the infection in the first place.

Several weeks before she was hospitalized, my mother had gone to the dermatologist because of a suspect skin cancer on her shin. The dermatologist burned off the pre-cancerous tissue with dry ice and sent her on her way. A few days later she found her leg had begun to throb. She was given a prescription for antibiotics, and when the sore stopped throbbing she ceased to take the pills. This was a mistake. The infection remained in her body. And it moved to an area of vulnerability. In this case, the area of vulnerability was her heart.

Five months after we drove her to the hospital, my mother went back for the surgery she needed to have on her damaged heart. She was told that, depending on what they found when they opened her up, her heart valve would be repaired, or she would receive a replacement. The replacement would come from a pig, and as a consequence she would need to be on blood-thinners for the rest of her life. My mother was told that when they opened her up, the doctors would stop her heart and deflate her lungs. For six minutes she would be technically dead, but she would be placed on a heart and lung machine, which would keep her alive. “How do you know my heart and lungs will start up again when you take me off the machine?” she asked. The doctor shrugged. “They just always do,” he said.

The doctors repaired my mother’s damaged heart. They sewed her up. When she woke up she felt like she was drowning. It hurt to cough, to laugh, and to walk. When she was at last sent home, I got to see my mother’s scar. It was sore, and purple, and stretches now across the left side of her pale, freckled chest.

My mother came home, her scar healed, and it was a comfort to hear the regular clinking of her gold bangle on her wrist as she walked down the hall at night. But her skin was a battleground now, and over the years it became a greater threat than her repaired heart. Every year since her hospitalization has involved the removal of solar keratoses. Band-Aids routinely cover her arms and legs, as once they covered my grandfather’s.

In 2010 my mother developed a rash on her face and her arms. The rash was a pre-cancerous growth of thick, pink scaly skin, growing in all the places she’d tried to roast herself golden when she was a baby-oiled teenager in the schoolyard. The dermatologist prescribed her a course of Aldara. Aldara works on the immune system. It causes the body to locate the pre-cancerous cells on, or underneath, the surface of the skin, and throw them up to the surface. My mother’s face required three course of Aldara. At first her skin broke out in a mean red rash, like a knee scraped on gravel. Then the cancers began to scab up. Standing in line with my mother at the supermarket after the scabs had broken out I observed a little boy in the queue over tug at his father and ask what was wrong with my mother’s face. He was frightened of her.

My mother applied the cream every day until the scabs fell off. The cream got rid of the cancers, but the burning-off came with a list of warnings from the dermatologist. No more sun. She cannot go outside without rubbing a protective layer of sunscreen over her skin, to shield her from the UV radiation that travels in the glare. At the beach, my mother sits under an umbrella, wearing long shirts to cover her damaged skin.

VII. THE SECRET OF THE SHRIMP

In 1925, when my grandfather was a year old, Prime Minister Stanley Bruce re-iterated the country’s commitment to a white complexion. “It is necessary,” he said, “that we should determine what are the ideals towards which every Australian would desire to strive. I think those ideals might well be stated as being to secure our national safety, and to ensure the maintenance of our White Australia Policy to continue as an integral portion of the British Empire. We intend to keep this country white and not allow its people to be faced with the problems that at present are practically insoluble in many parts of the world.”

But the White Australia Policy didn’t last. Over my grandfather’s lifetime, the policies meant to vouchsafe the British character of Australia were gradually dismantled. Waves of Southern European migrants arrived after World War Two. Another wave of Asian migration began around the time of the Vietnam War. By the time Australia reached the 1980s, the country was patting itself on the back for its multiculturalism, its inclusivity, and its friendliness. But Australia is not inclusive, and the thing it calls friendliness is a more insidious, unpredictable creature than it would lead you to believe.

In 1984, Tourism Australia launched a series of advertisements featuring Paul Hogan, the actor made famous in the movie Crocodile Dundee. Tourism Australia invited Americans to hop across the Pacific. Hogan warned Americans that they’d have to get used to a couple of local customs, “like getting suntanned in a restaurant, playing football without a helmet, and calling everybody ‘mate.’” In another ad Hogan stands atop the Sydney Harbor Bridge. “Aussies like to make you feel at home,” he explains. “It’s the friendliest place on earth. The beaches are crisp and clean. The beer is cold. And there’s plenty of shrimps on the barbie.”

Even if we weren’t alive when these advertisements aired, most Australians know about Paul Hogan on the Harbor Bridge, inviting the Americans over, throwing “shrimp on the barbie.”

The national joke is that none of us, not a single one, uses the word “shrimp.” We eat prawns in Australia, not shrimp. But that was not the outward face we needed, or wanted, to present to the world. We wanted to tell you a different story about our country, and we wanted to invent a different language to convince you we were larrikins, top blokes, mates looking out for one another down under, in the land of the fair go.

In August 2018, senator Fraser Anning stood up in the Australian parliament to deliver his maiden speech. Anning invoked the era of the White Australia Policy as a golden time in the country’s history. He argued that many Australians want to return “to the predominately European immigration policy” which existed before the 1970s. He argued that the country needed a plebiscite to decide on whether “non-English speaking immigrants from the third world” and Muslim immigrants should be allowed entry to the country. He cited all the familiar ghosts of the right wing imaginary—rampaging African gangs turning Melbourne into a war zone, ISIS-supporting Muslims stalking the streets of the suburbs, terrorism, welfare dependency, and laziness. He advocated a “final solution” to “the immigration problem,” and then swore he didn’t know what else a “final solution” might refer to.

VIII. ONLY A MATTER OF TIME

Every morning I apply seven different things to my face: a copper peptide solution, a toner, essence, caffeine solution, an ampoule, a moisturizer, and sunscreen. At night I apply acids and sheet masks, all sorts of chemicals and creams that promise to brighten, even tone and texture, diminish blemishes, and reduce the signs of aging. In the bright light of the bathroom, if I study my reflection for too long, I can see the future of my face. The deep lines that will form on my forehead, the sunspots on my cheeks, the crinkling around my eyes, the slow droop of flesh, the legacy of my childhood, my family’s love of the beach, our admiration for a lovely golden tan. I don’t believe the serums and moisturizers can stave it off. As Susan Sontag wrote, “the collapse of the project is only a matter of time.” They’re just the only thing I have to stave off the panic—the knowledge that I burned on Ventura Beach in California earlier this summer, and that I was meant to go to the dermatologist for a check-up six months ago, and that the mole on my forearm never used to be as dark as it is now.

The coming damage looks me right in the face every time I see my mother and notice the red and white scales and barnacles that grow on her arms now. It seems logical that whatever gold-corroding thing is nested inside my mother and my grandfather’s bodies could just as easily string its scabs across the length of my skin.

Our bodies contain the story of our individual lives, but they also contain the stories of our nations, and their policies. We might enact new legislation and initiate a new era of reconciliation and open mourning for the sins of history. We might take away Little Miss Coppertone’s tan line and give her a one-piece swimsuit. But the body doesn’t forget, and the sins linger deep below the surface. The cells of the body remember the sunshine, the beach, the roar of the surf, the jellyfish and the hot chips and the baby oil, the flush, the peel, the aloe vera and calamine lotion, the rough sheets. The cells of our bodies remember and they may, eventually, contain our endings.

Just outside Ballarat is a tourist town called Sovereign Hill. The town is meant to reproduce Australia as it was in those first gold rush years after 1851. Men ride on horseback and women wear bonnets. There is a blacksmith, a saloon, and a farrier. I was eight when my father decided to take me.

On the edge of a dusty creek bed, I lowered a pan into the water. The muck sieved through the small holes, and gradually I began to see small specks of gold. A man helped me collect the specks, and gave the nuggets of gold back to me in a small vial of water. I inquired how much my gold was worth. The man laughed. “That won’t get you very much anymore, love.”

Over the years, the vial was lost, but I have thought about that gold for years. The man at Sovereign Hill was right when he said that the gold wasn’t worth much. Its value was in its cold, aquatic glitter. It was hard to believe that something so lovely could emerge from such a landscape. It was the product of deep geology, a timescale well beyond the human, transformed in the body of the earth and offered up on the surface of its skin.

The memory of the gold is bittersweet, now, because it represents nothing more than an unobtainable dream. Like the gold leaf paintings of my uncle, the gold was beautiful and bright and it could not reproduce reality, but for a while there, it was all we could see.