If we find it easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism, it is perhaps in part because, as Pete Brooks points out in his essay “Prison Obscura”, capitalism is hard to see. Yet, we are also challenged to imagine the end of things we do see all of the time. In Are Prisons Obsolete? Angela Davis finds that the commonality of prison in our “image environment” contributes to our inability to “question whether it should exist. It has become so much a part of our lives, that it requires a great feat of the imagination to envision life beyond the prison.” Prison is normalized, taken for granted, and “one of the most important features of our image environment”:

Even those who do not consciously decide to watch a documentary or dramatic program on the topic of prisons inevitably consume prison images, whether they choose to or not, by the simple fact of watching movies or TV. It is virtually impossible to avoid consuming images of prison… this has caused us to take the existence of prisons for granted. The prison has become a key ingredient of our common sense. It is there, all around us.

The other day I was reading this passage at a shelter where I volunteer, the only family shelter in my county. The need far outpaces the resource. The shelter is full of children who have been living unsheltered sometimes for years. The shelter has an open-ended stay policy which means families who get space there can stay as long as they need to and they get help finding permanent housing. The shelter has a common room with a large television, which was on. At the moment I happened to glance up from my reading, there was a prison scene playing on the screen. What are the odds? The odds are good, is her point.

So how should prison be represented, if we need to represent it differently, in such a way that we don’t “take the existence of prisons for granted”? Brett Story’s film, The Prison in 12 Landscapes is one answer. Story represents prison without ever bringing her camera inside of one, showing, instead, how American prisons are produced by everything around them.

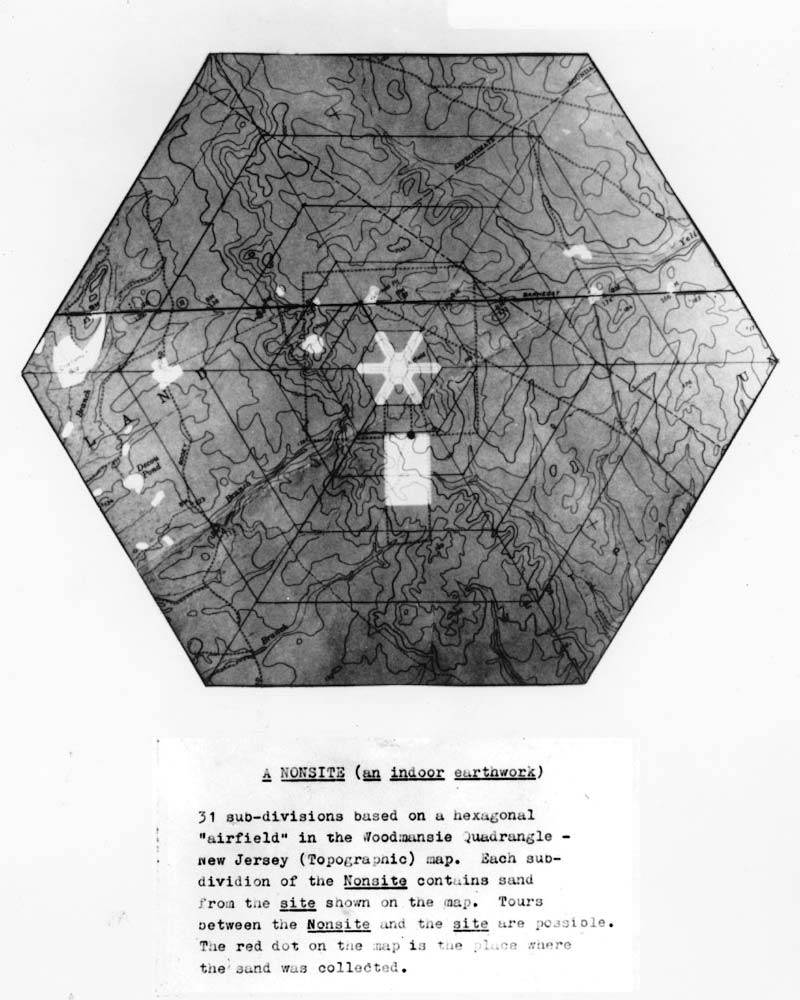

In his “Provisional Theory of Nonsites” the earth artist Robert Smithson wrote about his concept of the ‘Nonsite’ in which “one site can represent another site which does not resemble it.” One site becomes a metaphor for another. The space between sites, too, can be “one vast metaphor” making evident the non-local, non-perceptible conditions of possibility for locally perceptible phenomena. Whether or not she is influenced by Smithson, Story’s film seems to me a good example of a politically and ethically engaged way to use the concept of a Nonsite. She manages to make us think about prisons differently, by showing sites that are not prisons but that contribute to imprisonment, helping us to see how ‘carceral logic’ is pervasive. For example, any social process that produces and exacerbates poverty, anywhere that social services are lacking or inadequate, anywhere that good education is not well supported, all of this is productive of incarceration.

Story’s film, in showing prison by not showing it, also shows the way in which prisons disappear people.

If prison is a place for disappearing people—for “surplus populations” as carceral geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore puts it, referring to those excluded, underemployed and unemployed people that capitalism produces, as a highly exploitable labor force, and whose incarceration provides employment for those whose paychecks rely upon imprisonment (be they prison guards, prison builders, or prosecutors) it is the function of systems outside and beyond prison to make that disappearance possible, be it systemic lack of economic opportunity, public education and healthcare, affordable housing, or profoundly immoral incentives (overtime pay for arrests resulting in abusive, discriminatory police sweeps; the practice of forfeiture whereby police departments confiscate people’s belongings and valuables; career-advancement for prosecutors, etc.).

The misuse and abuse of their budgets by school boards to fund police in schools (School Resource Officers, or SROs) in reaction to school shootings is another example of carceral logic outside of prisons that creates incarceration, in this case by disappearing children into prisons, from schools: the school-to-prison pipeline. Even some police acknowledge that SROs are no solution to school shootings. Instead their presence causes increasing arrests and incarceration specifically of children and youth of color; children with special needs; and children in need of mental health services. The recent adoption of facial recognition surveillance technology in some schools seems destined to compound the problem of violence against schoolchildren.

What the correlation between police in schools and rates of incarceration reveals is that decarceration begins outside of the prison, wherever decisions are made about, and actions are taken with regards to, the provisioning of the public good. Gilmore describes prison abolition as a “theory of change” that entails the active creation of that which would obviate prison. Stefano Harney and Fred Moten describe abolitionism as: “Not so much the abolition of prisons but the abolition of a society that could have prisons, that could have slavery, that could have the wage, and therefore not abolition as the elimination of anything but abolition as the founding of a new society.” Founding a new society means (re)creating and enacting new ways of being that transform relationships and conditions in such a way that interpersonal and state violence don’t follow.

So abolition is two-pronged: create the new society, and the dismantling of prisons will follow. For example, the shelter I mentioned follows what could be described as an abolitionist credo: housing first and wrap-around services. The creation of housing and social services de facto “abolishes” homelessness for those who can access them.

For another example, Alex Vitale, the author of The End of Policing offers a straightforward solution to the school-to-prison pipeline: remove police from schools (abolish) and replace them (create) with educators, counselors, nurses, and staff trained in transformative justice protocols; precisely what teachers in the recent Chicago school strike demanded. What needs to be added to the list is provisioning educational and retraining opportunities for working class prison staff among whom are found some of the highest suicide rates of any profession. (In Denmark prison staff get six years of educational training for their positions. The training includes psychology. In Washington state the core training is six weeks and the focus is on security.)

In Are Prisons Obsolete? Davis describes mass incarceration as the “most thoroughly implemented government social program of our time.” Despite its inefficacy and destructiveness, prison construction began booming even as crime was in decline, creating an enormous economy around itself that has only grown over the past half-century.

The loss of agency with regards to this substance, this entity, this currency called time, the loss of the ability to self-determine the disposition of time is literally the way we describe punishment: to be “doing time” is the imposition of quantities of time, the disposition of unchosen qualities of time, in prison. The productivist work regime does not, of course, stop in prison where the twinning of barren time and exploitative time is taken to an extreme.

In The Burnout Society Byung-Chul Han argues that compulsory productivity leads to a certain degree of un-freedom for everyone: “One exploits oneself… exploitation is possible even without domination.” For Han “The reaction to a life that has become bare and radically fleeting occurs as hyperactivity, hysterical work and production. The acceleration of contemporary life also plays a role in this lack of being. The society of laboring and achievement is not a free society… in this society of compulsion, everyone carries a work camp inside.” Perhaps we ought to consider that, in addition to its prevalence in the image environment, another way prison is normalized is by means of mass capitulation to what Kathi Weeks describes, in The Trouble With Work, as the ‘work-regime.’ If prison is normalized, so is the mandate that everyone should be economically productive. All those who are not, be they elderly, young, ill, poor, burdened with debt and ‘bad’ credit, unemployed, or otherwise economically marginalized, are, accordingly, subtly or grossly stigmatized.

Sitting in a circle on a Saturday afternoon at a women’s prison where I facilitated a writing group last year, a woman in on drug charges for the second time in her young life spontaneously began to tell us about a dream she had the night before.

In the dream she is looking out of a window. She sees her brothers approaching, coming toward her. She waves and says their names. And then she hears a voice saying recall, recall. She wonders what they are trying to say. They float away from her. She wakes up hearing the word recall over the loudspeaker, calling everyone to work.

In the U.S., in which over 2 million are incarcerated, there are said to be three degrees of separation between any given person outside and someone inside. Degrees of separation between you and someone who is or has been incarcerated will track along lines of class, education levels, and race. This tells you not so much who the criminals are, as who is vulnerable to being criminalized, assumed criminal, and treated, as it were, criminally. Winter is an apt allegory for this state affairs, for winter is the season of withdrawal, of absence.

Yet Gilmore notes that there is no reason to think that decarceration should take a long time. Where there is political will, she observes, we take action quickly. Her example is the 2008 bailouts, the “Emergency Economic Stabilization Act” et al. As an example of how quickly legislators can act when motivated and pushed, in November, 2019 about 500 people in Oklahoma had their sentences commuted. They were released from prison in one day.

If prison is winter in America, decarceration is the American spring.