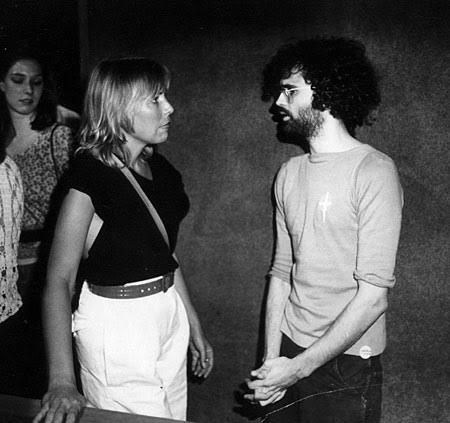

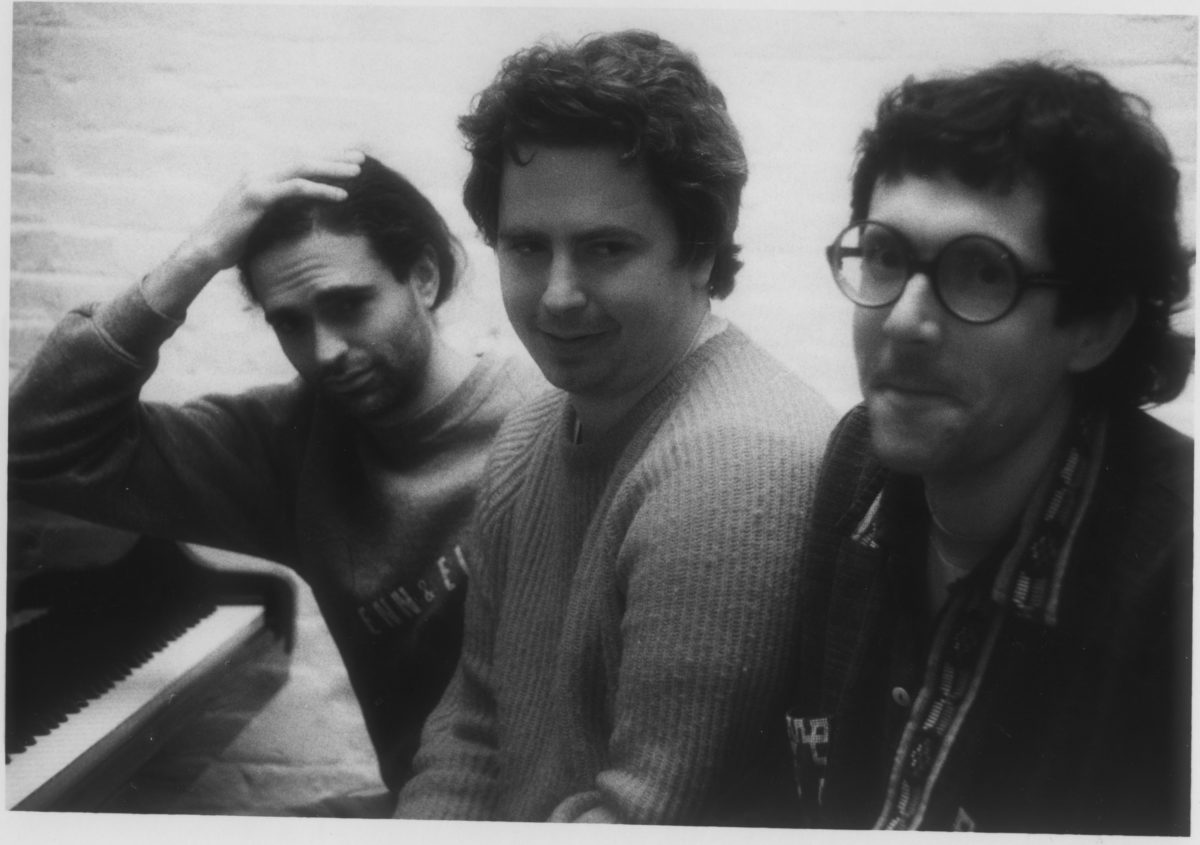

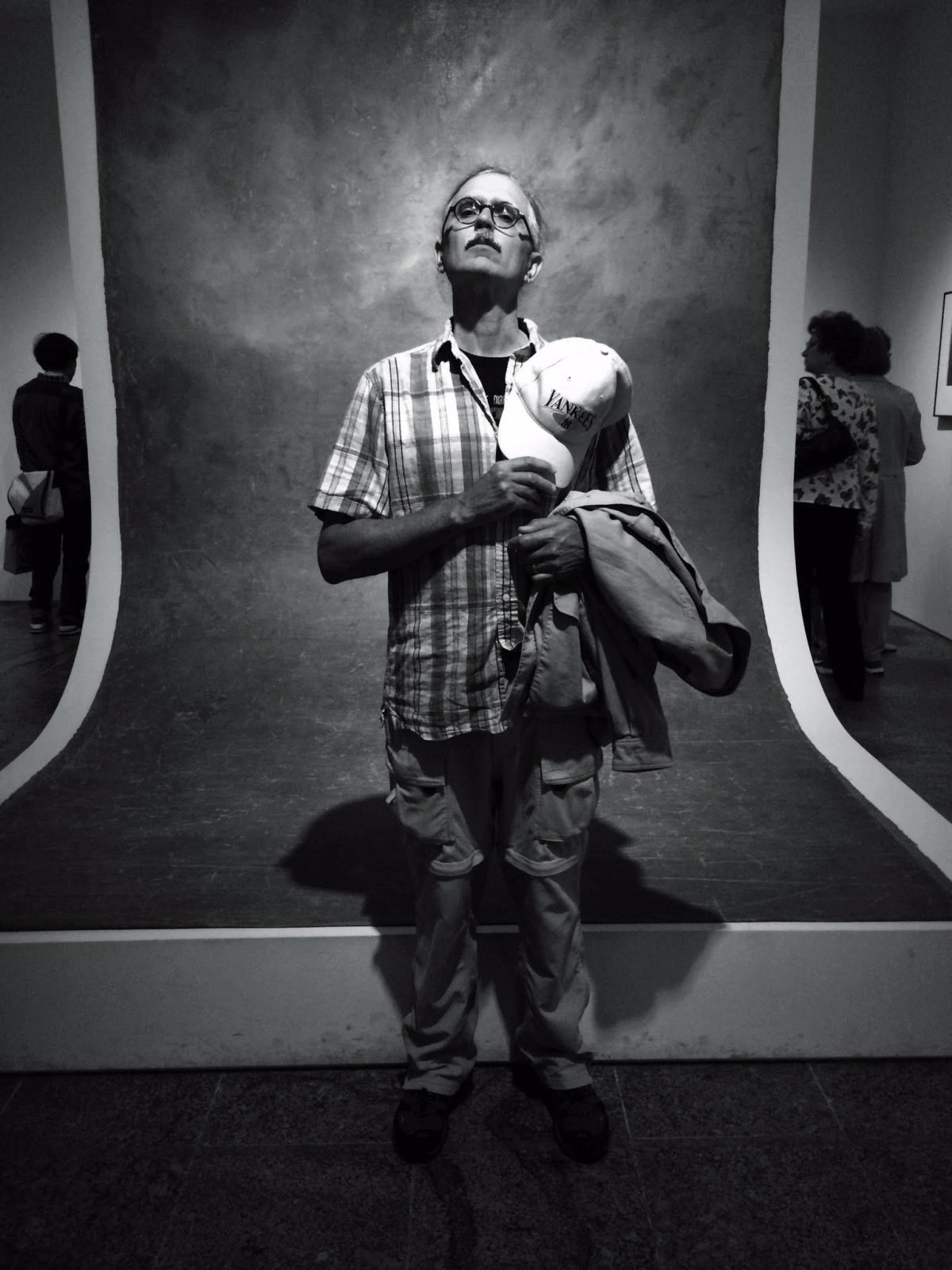

The producer and songwriter and multi-instrumentalist who goes by the name of Kramer had a streak, in the eighties and nineties, of selecting and developing for his label Shimmy-Disc albums by some of the most influential bands of the period (such as Daniel Johnston, Ween, and King Missile, to name but a few) as well as producing seminal recordings by Galaxie 500, Half Japanese, Low, Royal Trux, Urge Overkill, Palace Brothers, Pussy Galore, and on and on. So influential was Kramer’s production style, that he practically patented a certain approach to reverb that was all his own, however widely imitated by others. He also wrote for and was the musical director of the performance art band Bongwater, with actress Ann Magnuson, and wrote and performed with Penn Jillette and with outsider songwriters like Jad Fair, Paleface, and Danielson Familie. His most recent album, under the moniker Let It Come Down, Songs We Sang in Our Dreams, released on vinyl this month from Shimmy-Disc (in partnership with Joyful Noise), is a collaboration with vocalist Xan Tyler, and like all things Kramer it is luminous, spooky, psychedelic, genreless, heartfelt, and very smart. In short, if there was a creative and uncompromising musical movement in the last forty years of independent music, Kramer either played in it, or knew and later collaborated with the exemplars of the form. He has passed from jazz to free improv to psychedelia and show tunes and Brill Building (with Bill Frisell) and back again. He knows everyone, but more than knowing them, he can see into the singularity and importance of a great variety of musicians, likewise into their work. Like a sort of indie rock Cassandra, he seems to be doomed to understand the greatness of all this work without being able to profit outlandishly from his insight, which only makes his testamentary remarks more acute. I’d long awaited a moment when I could pigeonhole Kramer for an interview, and last year the moment finally arrived—through my admiration of the production work he did on the songs of a friend of mine, Emily Rodgers. When the time came to conduct the interview below, I had been stockpiling the questions for years. Little did I know that Kramer was so open and so discursive that I could manage an entire interview with a minimum of intervention of any kind. Nevertheless, as I think the following pages will indicate, a life story can easily be undertaken, or a portion thereof, with just three questions. With any luck I will someday get a chance to ask him a few more.

—Rick Moody

QUESTION #1: I’m really interested in how you ended up playing in New York Gong and what that experience was like. Can you tell that story? Was that when you were first playing in NYC?

KRAMER: Okay, Rick. So you’re starting with my very first professional gig, though it was anything but professional, by even the loosest definition.

It all happened through Giorgio Gomelsky, to whom a friend in Woodstock had introduced me on a trip into NYC to see Captain Beefheart at the Beacon Theater in 1978. We took an instant shine to each other. Giorgio was a real charmer. Old school Eastern European affectation, though he was actually born in the USSR (in Georgia, to be precise) and raised in Switzerland. He dressed and carried himself like some crazy Hungarian or Czech, with a beard that pointed straight into your eyes like a dart as he lifted his chin and talked down his nose at you. A lovely character, he was. Giorgio had a penchant for telling anyone who’d listen about his grandest pie-in-the-sky plans. His entire life was about grand plans, though only about one percent of those plans ever materialized once he arrived in NYC and bought that building on 24th street, which came to be known as ZU PLACE, or ZU HOUSE, or simply ZU. “I’m going to be making a whole new scene in NYC and it’s all going to happen here! Fuck The Factory! Fuck Warhol, man! ZU PLACE is the place!”

My main memory of ZU PLACE was circumnavigating the Doberman pinscher turds dotting mostly the 3rd floor but also pretty much anywhere else. You try stopping a Doberman pincher from shitting and see where that gets you. I think Giorgio had three of them, and he didn’t like taking them out for walks, so he just kept them all locked up on the third floor and let them shit there.

Everyone lived in abject fear of those dogs, and the dogs lived in abject fear of Giorgio. But by the time I left town after the Gong tour crashed and burned, Giorgio had joined us lowly commoners and the dogs had taken total control of the entire building. We were their tenants. That’s what I remember most about ZU PLACE. Whenever I was there, I lived in the basement with whatever other musicians were passing through town. Giorgio’s door was always open to musicians, artists, poets. He never once paid any of us, but I never doubted for a moment that he loved us. Music and musicians—that was his whole life, and he loved his life like no one I’d ever seen before. In fact, he was my first European friend. I became convinced that all Europeans must be like him, and that Europe must be like heaven. I was just a stupid kid.

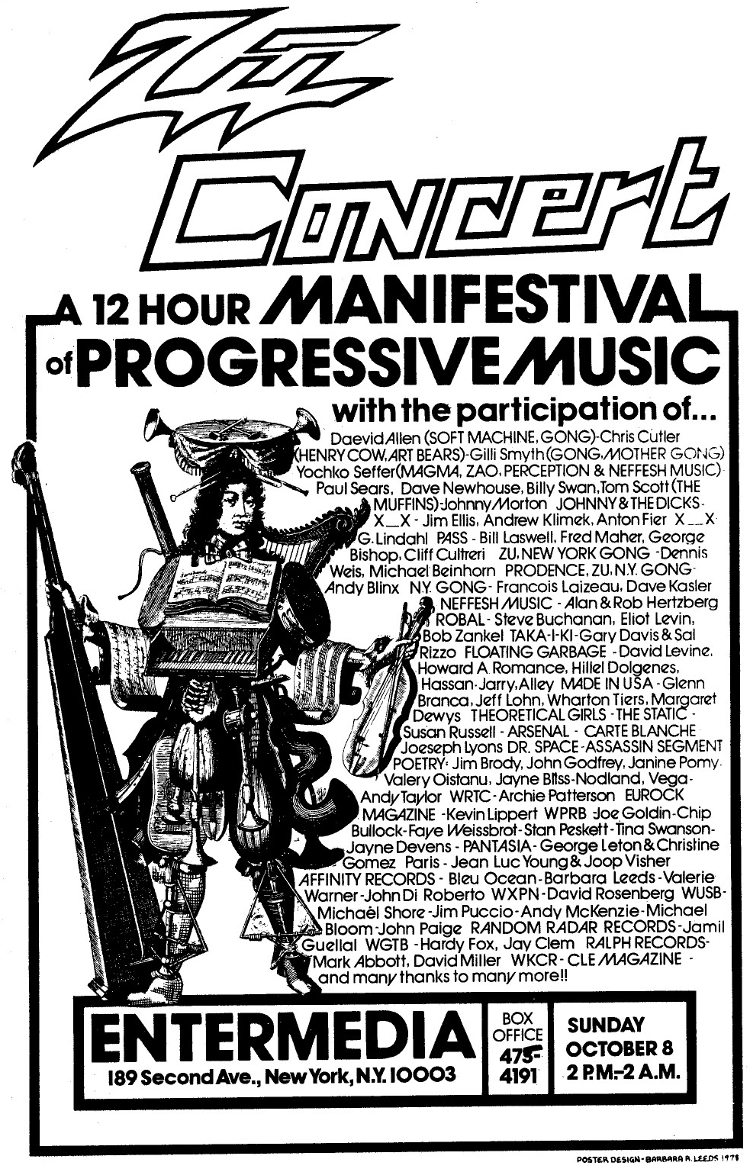

One day Giorgio starts telling me about how he’s going to have a big week-long festival in NYC and bring Daevid Allen and Gong and Magma and Henry Cow and Slapp Happy and the Plastic People Of The Universe and Robert Wyatt all these other art rockers over for their first stab at an American audience. Well, he did actually pull this off but not as a week-long event, and not with all the artists he’d envisioned would come running when he called. It was, as I recall it, a two-day “ZU MANIFESTIVAL.”

I got to work for Giorgio as one of his many “assistants” and got to meet Daevid Allen from Gong, who was tripping pretty much 24/7 and couldn’t really communicate in the traditional sense. After the festival ended and everyone went back to whatever country they’d flown in from without having been paid a penny for their performances (a decades old tradition for anyone who fell under Giorgio’s influence), Giorgio immediately began trumpeting his plans to bring Daevid and Mother Gong and Magma and Chris Cutler back to tour North America for six months, with his “Zu Band” providing the backing for each act. This turned out to be a secret plan of his to promote his new darlings, Zu Band, led by Bill Laswell, who cut quite a figure back in 1978, looking pretty much exactly as he still does today. Giorgio was utterly enamored with Bill. Like totally. Like he was in love. To Giorgio’s mind, Laswell was the Second Coming, and the only person who believed that more than Giorgio was Laswell himself.

Giorgio had somehow found out that I wasn’t just a keyboardist but that I also played trombone, and that’s actually what got him excited about my joining Gong.

In his thick Swiss accent, he’d say, “Daevid loves the trombone. You have to join the band. We’ll have trombone, trumpet, saxophone, flute, maybe French horn, man! Can you play French horn too? Man that would be great! and maybe even a tuba!”

“I don’t play the French horn, Giorgio. In fact, to be honest, I can barely play the trombone.”

“Great! We’ll teach you! We’ll get you lessons starting this weekend! Go get your trombone! And we’ll buy you a French horn too! You can play everything! No, wait. Maybe we can rent a French horn! Then we can have extra money to rent you a tuba, and maybe a little trumpet like Don Cherry plays! You can play that too!”

So I came down from Woodstock with my trombone, which Giorgio excitedly snatched from my hands the moment I’d taken it out of its case and assembled it.

“Jack Teagarden,” he whispered, and then blew into it and made a horrible sound, not unlike the sound you might hear if someone had somehow found a way to get a toilet to make music. It was awful. He’d play for a few minutes, and then stop, look into my eyes for approval, and, upon receiving none, quietly repeat his whispered mantra: “Jack Teagarden”. This went on, and on, and on. I’ll never forget it. Laswell was there, and I think it was the only time I’d ever seen him laugh out loud.

Daevid arrived in NYC, haggard and pissed off after a long flight from Australia in coach class, courtesy of Giorgio. Giorgio was “out of town” at the moment, which I later came to learn was Giorgio’s standard method for avoiding confrontation with musicians who want to take up old business with him upon arrival in town, or complain about new business. He just waits for the person’s flight to arrive, and then he leaves town. Eventually Daevid settled in, and we got to talking.

“Giorgio says you want a trombone player in Gong,” I said. “That seems crazy to me.”

“What? Fucking Giorgio said what? A bloody fucking trombone? He fucking said that? Right. So fucking Giorgio Gomelsky is now in charge of who plays in Gong, is he? Right. Well, we’ll just have to fucking see about that.”

“Daevid, I play electric piano and organ, and I have a mini-moog and an Echoplex. I’m your keyboardist and synth wizard.”

“Right. That’s sorted, then. Where’s Giorgio. Fucking out of town, right? Of course, he’s fucking out of town. He’s always out of fucking town when he owes someone money. Someone like me, for example. Mother. Bloody. Fucker.”

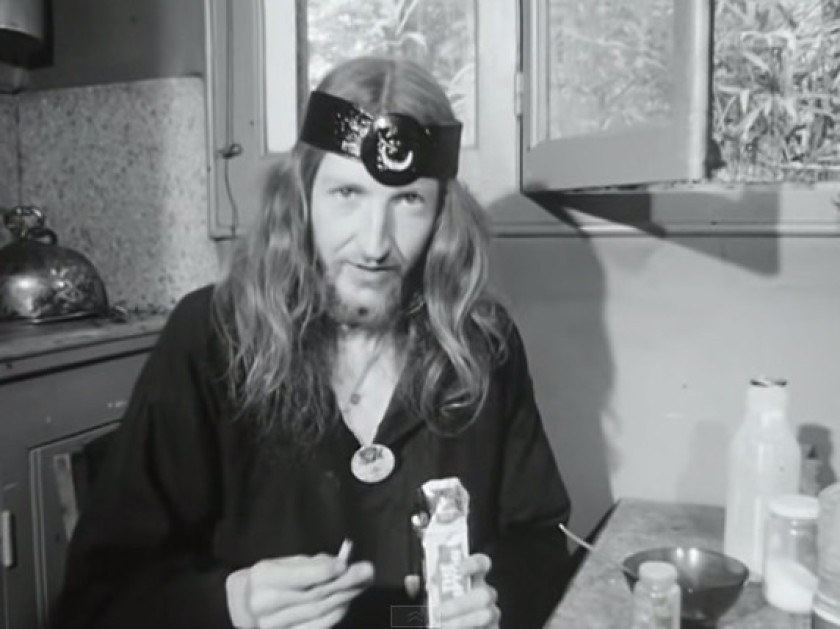

This was not the Daevid I met the previous year at the Zu Manifestival. This was a reasonably coherent, angry hippie with a chip on his shoulder. I soon found out that Daevid had just recently stopped sprinkling LSD on his cornflakes every morning, and was seriously experimenting with a life of sobriety. This was not something he was just trying out, just for fun. He was dead serious about having wasted his consciousness on mind-altering chemicals, and wanted to spend the rest of his life sober, meditating, and making music that “brought people to a higher plane without drugs.” What’s the difference, I thought. All I really saw was a sensitive man who was newly broke and wondering why it had all come crashing down around him, and finding no one and nothing to blame but himself, or drugs. So he chose to blame the drugs. He had just turned forty. I had just turned twenty. He liked to point that out to me as often as possible. He felt as though his life had been wasted, and he was dead set on making sure that I didn’t waste mine.

He said to me: “You know what I was doing when I was twenty, Mark? I was standing next to Terry Riley on a street corner in Paris selling copies of the International Tribune. Look what you’re doing at twenty. Throwing your life away. Did Giorgio tell you he’d actually be paying you for this gig? Bring me a laugh bag so I can vomit into it. You’ll see all about Giorgio soon enough and it won’t be long from now I promise you. I’m a fool. You’re a fool. We’re all bloody fools.”

Psychedelic music had been mercilessly run over by the Mack Truck of “punk” music in the late 70s, like a cat crossing the road. It all happened so quickly. I recall a gig in Cleveland at a massive concert hall that had a smaller room downstairs with a capacity of 300. Gong played that smaller room. The Boomtown Rats played upstairs. [Bob] Geldof spent a good deal of his set whipping up the crowd between songs, taunting Daevid.

“Do any of you fuckers know who’s playing downstairs? Gong! Gong is playing down in the basement? What a bunch of hippy wankers! I think they need a beer, don’t you??? Why don’t one of you American pussies bring Daevid Allen a pitcher of Budweiser on me??? Come on! You wankers!”

As the tour progressed, it wasn’t just Daevid’s previous lifestyle that he was trying to jettison. It was the music he’d been making too, as Laswell and the music of Zu Band (later known as Material) slowly but effectively won him over. By the end, Daevid hated Gong and everything it stood for, which means he also hated himself. I didn’t know who he was by the time the tour was over, and I’m pretty sure neither did he. And it seemed as though nothing could have pleased Laswell more. Poor Daevid was the epitome of chaos.

By the end of 1979, I found myself on a dilapidated school bus with Laswell, Fred Maher, and Michael Beinhorn (we were just kids!), and the older generation; Daevid Allen, Gilli Smythe, Yoshko Seffer from Magma (the only member of that infamous band Giorgio could convince to come over from France), and the great, great Stu Martin, who only stayed for a few weeks before he realized that this wasn’t really something he should be doing and flew home to Paris to drink himself to death. He entertained everyone on the tour by getting plotzed every morning and screaming at us, “What the fuck am I doing here! I played with The Duke! Did you play with The Duke??? I was the youngest drummer ever to play with The Duke! And I was fucking white! Did you ever play with the fucking Duke?”

Stu was tons of fun. I miss him terribly. He pretty much ignored everyone onstage and seemed to just be playing drum solos most of the time, though he’d pop in and out of time with the band whenever it suited him. During the two weeks of rehearsals at Zu Place before the tour, I’d accompany him to the bar on 23rd Street every morning to make sure he’d be back in time for the start of rehearsal. He left his two VCS3 synthesizers with us when he left to go back to Paris. Beinhorn and I were huge fans of Eno (the VCS3 “Putney” was one of his main tools for “treatments” of other instruments in the early days). Stu had left one for me, and one for Beinhorn. At the end of the tour, Beinhorn disappeared with both of them. I was livid at first, but I couldn’t stay mad for long despite the fact that he spent the entire tour deriding me and basically being a total jerk to everyone who wasn’t in Zu Band, I loved the guy. I even loved Laswell.

The derision between individuals on that bus was more than palpable. There were two opposing clans: the old hippies, and the late 70s NYC hipster kids. Some of the French hippies just tolerated the kids by pretending they didn’t understand English. Gilli was made fun of mercilessly. I’d brought my old friend Bill Bacon in to replace Stu Martin, and along with another friend from Woodstock, alto sax player Don Davis. Soon, things started to come together onstage. By the end of the tour, in late May 1980, we had become one helluva hot rod, nailing those early Gong classics to the ceiling of every little venue we played in. Daevid battled his addiction successfully throughout the tour. He fell off the wagon and smoked pot once about midway thru, but it was a very bad idea and he didn’t do it again. He literally had a psychotic fit on the bus en route to our gig in LA, screamed at the bus driver to stop, and ran off into the Arizona desert. It was about 110 degrees out there and 150 in the bus within a minute or two, so it wasn’t long before all twenty of us had filed off the bus and out into the desert, watching Daevid’s receding figure getting smaller and smaller over the hills, the sight of which caused Bill Lawsell to observe,”It’s beautiful, isn’t it?”

Inspired by the sight of rattlesnakes, vultures circling overhead, and at least one pair of overalls and boots curled around a decaying carcass of unknown origin, Daevid soon made his way back to the bus, looking like he’d seen a ghost. He settled down after that, and behaved in a wholly civilized fashion, until the very last gig in NYC, which it seems, in retrospect, he was just waiting for. He blew off all of that pent up rage against himself onstage at the final gig, cursing everyone in the audience and pretty much every Gong fan on earth. Very upset, he was. But he did this about ten minutes into the set, after we’d been playing what each of us knew was our very best gig. The band was tight. Six months of pointless gigs had left us teetering on the fiery brink of perfection. We knew the songs, and finally, we knew Daevid. and Daevid knew that we had never played better.

So he stopped playing, waved us off, walked up to the mic, and let it all hang out. I’d never seen anyone so upset since my father found my hash pipe hidden behind the oil burner in the basement of our Long Island home. Daevid spouted the most vile diatribe against everyone and everything in sight, and plenty that wasn’t in sight. Then he just walked off the stage. By the time I got back to the dressing room, his guitar case and bag were gone, and I didn’t see Daevid again for years.

It was the beginning of a new stage for him; one in which he openly rejected his life of drugs and teapots and pothead pixies and briefly embraced what he had come to consider to be his new “punk” ethos. He cut his hair short, bought a leather jacket, hired Bill Laswell to create the music for his next LP, and renamed the band “New York Gong.” It was disastrous from conception to execution, and it died the sorry death that it deserved. These were the beginnings of some very tough times for Daevid, during which he bounced around the globe doing solo gigs for pennies and sleeping on floors.

But back to the dressing room at that particular Gong band’s final gig in late May or early June 1980. Apparently believing that either the promoter or 500 pissed-off Gong fans were going to tear him limb from limb, Daevid had made a dash for the hills, leaving Giorgio sitting there all alone, looking like his mother had just died right in front of him. This was the one and only big-money-gig of the entire tour, but Daevid had walked off the stage ten minutes into the show. Surely the promoter would refuse to pay.

As it turned out, entirely unbeknownst to the band, and perhaps even to Daevid, this never was a paying gig. Quite the contrary. It was a free gig all along. Giorgio had lied to us. He’d kept everyone on that bus with the promise of a big payday at the end of the tour: “…when we do all the books and tally up all the profits, man! What do you think we’re going to pay you after every show? Are you fucking crazy, man?!””

And now, it was time for the band to be paid.

I’ll never forget this as long as I live. It was my very first payday in music, and it was just a total myth, right from the start. Giorgio didn’t wait for us to ask. He started right in with his speech, which I would today assume was not the first time he had offered it up.

“You want to get paid. Who’s going to pay you? Me? You want me to reach into my pocket and take out everything I’ve got and pay you. Okay. I will do that.”

He stood up, and pulled out his pockets. They were empty. He reached into his jacket and pulled out his wallet. It was empty. He reached into another pocket and took out a money clip with about ten $1 bills. He fanned the bills out. Someone took them. I can’t recall who it was. I think we all knew this was coming. Anyone with a brain would have suspected it, but when you’re young, you still have this crazy thing called hope.

You hope that girl will love you enough to let you kiss her. You HOPE your parents don’t really hate you. You hope you’ll never do something totally stupid and find yourself in jail, or dead. You hope that if you ever have kids they’ll be born healthy and they won’t have cancer or schizophrenia, and you maybe even hope that they’ll love you, the same way your parents probably loved you too, even though you were so fucking sure they never did, not even for a second.

And so ended my first “professional” gig. And so began my “career” in music, wherein just a scant five years later, after less than six months on the road with Butthole Surfers, I’d learned that if I wanted to live past thirty, I’d better find a smarter way to stay in music than by being in a fucking band.

When Daevid died a few years ago, his family sent me a picture of the teapot in which his ashes were laid to rest for a few hours before they set it upon a small floating contraption made of dry wood, set it ablaze, and cast it out into the Aussie surf, in what I believe they felt was as close to a Buddhist ceremony as they could muster.

QUESTION #2: I’m interested in how you wound up in Karl Berger’s orbit, and what was that like? Wasn’t that sort of jazz training? Did you want to play jazz?

KRAMER: I absolutely would not be here today, if not for Karl Berger and the Creative Music Studio.

At CMS I met John Zorn, Eugene Chadbourne, Fred Frith, Ralph Carney, Ed Sanders, Anne Waldman, Gregory Corso, John Giorno. The list would fill a book. There were literally dozens of days I’d wake up and find myself mingling with some of the world’s greatest poets and musicians, or with a living god of some eastern religion.

At CMS in 1979, along with about ten or twelve other crazy students, a band we called Mind-Control-Salsa Orchestra got a tiny bit more serious and became Swollen Monkeys. The music producer at SNL in NYC, a genius named Hal Wilner “discovered” us and brought us into a professional recording studio. He produced our first and only LP. It was basically a comedy record with a big band playing fast and loose, with song titles like, “I Can’t Cumplain” and “Hose-Anna” and “Fully Baked.” The LP title was, Afterbirth of the Cool. If Spike Jones had sucked, he’d have been Swollen Monkeys. We weren’t funny even for a second, but we all thought we were. What can I say? We were just kids. We were all good musicians, but the only goal was to have fun and look down from the stage and see people smiling and laughing.

Then after the LP came out, a couple of people in the band wanted to get serious, and proclaimed themselves the “bandleader.” It was all over soon after that.

As a teenager, along with my love of The Beatles and those first few Brian Eno records, I’d been a rabid consumer of jazz. All kinds of jazz, from the perfections of Bill Evans and Chet Baker, to the cacaphonies of Ornette, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Eric Dolphy, Miles, Albert Ayler. Too many to name. I also loved the “New Music” composers. John Cage’s book Silence had changed the way I thought and felt about music, life, the world around me, the world inside of me. Morton Feldman, too. I’d first seen his name in the pages of Silence: “Feldman is a large man who falls asleep easily.” That got me pouring through the racks at the Sam Goody record store at the Smithtown Mall on Long Island, in the Classical section, as there was no other place one might find him. And I did. There were two LPs available. I bought both of them. One was Rothko Chapel. Whoa. Be still my heart. I fell in love with Morton Feldman.

I saw Sun Ra a lot. He seemed to always be playing in NYC, with the full orchestra, with a small orchestra, or solo. One night I arrived at some club and there was a sign on the door. “SUN RA plays FLETCHER HENDERSON, TONIGHT ONLY.” My mind was summarily blown. I was smoking a ton of pot around this time of my life, so right away I got this whacky idea of becoming an “arranger.” I studied the works of Henderson, Gil Evans, George Russell, and even the orchestral arrangements Nelson Riddle had composed for Frank Sinatra. I enrolled in open classes with George Russell at the Village Vanguard. I think it was the Vanguard. They let him teach there during the day, before people like Sonny Rollins and Sun Ra came in at night to remind people of what jazz really was, what it really is, and what it really could be.

I was also deeply into the London jazz scene and the “free improvisers” like Lol Coxhill, Steve Lacey, and of course Derek Bailey, with whom years later I did a trio gig with at The Mudd Club in 1980, alongside John Zorn. Steve Maas, the owner of the Mudd Club, was a friend, and he was always telling me I could do whatever I wanted to do there. All I had to do was call him directly. “Don’t call the booking agent. I’m the only real booking agent here. You just call me and then you come and play. Just don’t do a no-show. You book a gig here and then don’t fucking show up, and I’ll never book you again.”

I think James White & The Blacks had just done a no-show there and Steve was pissed. So he let me bring in John Zorn and Derek Bailey (neither of whom he’d ever heard of) with one sole caveat: we’d better fucking show up. Fair enough.

Then came the big night. The doorman tried to not let us in. there were drag queens dancing on the bar. No one knew who we were or why we were there, and no one stopped drinking and behaving decadently as we played. Derek loved that. I recorded it on my Revox A77, which I’d bought the day after reading Eno’s credits on No Pussyfooting. I like to fantasize that the tape actually still exists somewhere, somewhere I might one day find it.

Anyway, I was deep into the shit almost no one else was into. To me, this strange music was so beautiful. To me, it sang of freedom. I couldn’t get enough of it. I’d try to turn people on to it, and after a few minutes of not really listening at all, they’d say deeply stupid and ignorant things, like, “That’s not music.”

Nowadays, so-called “free music” is just about the last thing I’d want to listen to. I’m back to Nelson Riddle full throttle, whenever I’m not listening to the Bill Evans trio.

And now I figure the only thing I really know for sure, the only thing I’ve figured out for absolutely certain, is that I’m still completely confused.

I was eighteen. I had a little beard like Robert Fripp had in 1974, and I fancied myself a composer/arranger. I wanted to study with the great avante-garde composers. I wrote letters to John Cage. He wrote back a few times. Then finally he replied with a single sentence, “I cannot teach, but you may wish to consider contacting Christian Wolff.” I finally met him years later at a Poetry convention in NYC, but it was during the time that he and Merce Cunningham were being “silent.” I walked up to him and shook his hand and introduced myself.

Cage said nothing. Not a word. He just smiled and looked at me. I was a kid who’d shared a correspondence with him, and he wouldn’t speak to me. I was crushed. Then I saw Bill Burroughs walk up to him and start yammering in that ribbony drawl of his, and Cage did the same thing to him. He just grinned at him, like he was drunk on happy pills. Burroughs said, “Oh right. Sorry, John. I forgot…” and turned and walked away. I felt much better after that.

Since my early teens, I was a subscriber to DownBeat Magazine. Around the time I graduated high school, I saw a tiny little ad in the back pages for a place calling itself “CMS,” the Creative Music Studio in Woodstock, NY. It was actually about fifteen miles from Woodstock, but the word “Woodstock” sold big in those days. I saw the names of the “faculty” members listed in the ad; Director Karl Berger. Steve Lacey, The Art Ensemble of Chicago, Anthony Braxton (whose music I was briefly infatuated with at that time), and, god help me, founders; Dr Karl Berger and Ornette Coleman.

The ground shook.

At the bottom of the ad, it said, “Now Accepting Applications For Our Fall Semester—Send Self-addressed Stamped Envelope”.

I wrote and got my application within a week, along with a little brochure. Again, Ornette’s name was there, right up front. I could hardly breathe when I saw that. The brochure said something like, “CMS accepts a limited number of students so you must apply soon!”

It said to send an application fee of $50 and a cassette with whatever I wanted them to hear, and that Karl Berger himself would be auditioning each tape and hand picking his students. So I put a 60 minute cassette of what I felt were my most avant- garde noodlings, and a check for $50 into a padded envelope, and sent it back. Lo and behold, about two weeks later I got an acceptance letter, along with a note: “Please remit payment in full for the Fall Semester by August 1st or your space will be forfeited.”

I sold some shitty records from my early teens, briefly went back into the business of selling nickel bags of Mexican dirt weed to the locals, raised the $1000 I needed, and excitedly wrote out another check to CMS. And just before Labor Day, I was driving my little Volkswagen hatchback and my Mini-Moog and reams of Satie-esque “compositions”(which often looked more like paintings) up to the Woodstock Valley, where, despite the explicit driving directions I’d received in the CMS “arrival packet,” I got lost in the winding roads of Mt Tremper. Going around in circles, I kept seeing a little gray Datsun pickup that seemed to also be going around in circles. I locked eyes with the other driver several times before we simultaneously stopped at a crossroads, pulled up to each other, leaned out our respective windows, and asked each other, almost in unison, “Are you looking for CMS, too?”

This was Tom Cora, a man of about thirty whom I would soon learn had only just recently abandoned his lifelong passion for the guitar and bought himself a cello, for some odd reason that even he himself couldn’t articulate. Tom and I became fast friends and remained so until I gave him a handful of my Derek Bailey and Evan Parker “Incus” LPs. I told him that this music was called “Free Improvisation.” I told him it was the music that inspired me most, at that moment in my life. I told him to be prepared, because this music was unlike any other music on earth. I told him I knew he’d love it. He smiled, thanked me, and ran off to his room to listen.

Less than an hour later there was a knock at my door. It was Tom. He wasn’t smiling anymore. He handed me back the LPs I’d just loaned him, turned, and walked away without saying a word. He didn’t smile at me again for years, during which time he became an expert at not smiling.

I distinctly recall the next time he smiled at me. We were onstage together for the first gig by The Chadbournes. Eugene had just played the most gloriously stupid guitar solo I’d ever heard on a bluegrass speedcore version of “Are You Experienced?,” and we looked at each other and lost it. Laughed like hyenas, right there on stage. Eugene could do that kind of stuff to an audience, and he often did it to me onstage. That kind of music brings people together. Or back together, as was the case on that particular night.

Tom became one of the premiere cellists of free-improvisation. Scratch that. He became the cellist of the Free Improvisers movement. He died tragically of melanoma, twenty years ago, at the age of forty-four. He was the first of us to die. On a rooftop in Switzerland, I believe. Maybe that’s a myth but that’s what I was told.

There was a “New Music Intensive” at CMS at which Christian Wolff showed up. John Cage, you recall, had in his last letter to me suggested I contact Wolff. I couldn’t get anywhere near him. He spent the entire weekend huddled with George Lewis, Richard Teitelbaum, Anthony Braxton, and Ursula Oppens. In his defense, George Lewis was always anxious to talk to the students. He laughed a lot. A beautifully huge, mountainous laugh. But the rest of the composers walled themselves off from the students. Despite the fact that the weekend was part of the school curriculum, and despite the fact that these 20th century illuminati were paid to be there with student-paid tuition, they acted like aristocracy and ignored the students en masse. I never got anywhere near Christian Wolff. One of many early disillusionments I was to experience in the halls of music academia of the 1970s. Another was being hired by Anthony Braxton as a transcriber for an upcoming piece he was composing for four orchestras.

“My transcribers make top dollar. Twenty dollars an hour. But you need to stay with me at my house for four weeks. I need 24/7 access. You gotta be there whenever I need you, and I work through the night sometimes.”

Working for Anthony Braxton for $20 an hour in 1979 and living in his house? Was this heaven? Was I dreaming? How could something so miraculous happen to me?

As it turned out, I was paid $10 per hour, but not until the end of eight weeks (not four, as he’d stated when he hired me), and the promise of staying with him in his house turned into a cot in an uninsulated shack with a wood-burning stove behind his beautiful Woodstock home. No running water, no electricity. Two gas lamps, a pile of dry wood so close to the stove that the whole place could have ignited like a cherry bomb at any given moment, and enough spiders already in residence to have me sleeping with one eye open for my entire tenure there. I hate spiders. There are few things I hate more. What do I hate more? The cold.

For the first two weeks, I worked beside him in his home whenever he called across the yard to me. Then one day he said, “Mark. I got a great idea. Let’s set you up to work in the shed, so you can be totally undistracted in there. You’ll get tons more work done in there than you would here.”

“But Anthony, I’m not distracted in here. And I don’t think my calligraphy will be worth a rat’s ass if i’m working out there in the cold.”

“Aw now don’t be a big baby. You just keep that stove working and you’ll be fine.”

I wanted to quit but I’d given up my room at CMS for the winter, and I had no place else to go. And I needed the money. The $20 per hour I never got, I mean. Never expect your heroes to be fine people. It’s far better to expect the exact opposite. Then you can be thrilled to death when you meet someone who treats you just as you would treat them. Hang on. Hang on just a little bit longer. You’ll meet good people. Eventually.

Arriving at CMS, I was surprised to find that this was no campus, but rather a summer lodge ill-equipped for the harsh Adirondack winters I would spend there over the next two years before leaving for Gong and warmer pastures. I parked my car and walked into the admissions office. Sitting behind a little desk was a little man named Jim Quinlan, the head administrator, who remains a dear friend to this very day. He now runs the Rhythm Foundation in South Florida (where he is responsible for every world music concert that takes place). After signing in and getting my room assigned, I walked out of the building and was met by the last thing I expected to see, ever, anytime, anywhere.

Crossing the lawn before me, with two Tibetan terriers in tow, was the immortal Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. If you don’t know who that is, you can Google him.I knew who he was. I thought I was dreaming. I’d read all the DT Suzuki I could get my greasy hands on. To make a long story short, CMS was 50% music school and 50% Buddhist retreat. And I mean serious Buddhist retreat. The kitchen was 100% vegan, much to the dismay of all the carnivore drummers who’d shown up thinking that because Jack DeJohnette’s name was on the faculty list, he’d be there as an instructor, instead of being off on tour around the globe with Keith Jarrett or Dave Holland, which is exactly where he was. He didn’t appear at CMS once, and that fact, coupled with the vegan diet, was enough to send some of those drummers marching into Jim Quinlan’s office to demand a refund. And whenever that happened, Karl Berger would suddenly appear to put his arm around them and convince them to stay, and they always did. Well, nearly almost always. I do recall one tall kid with horrible acne throwing rocks at Karl’s car before driving off in a huff of gas fumes and flying gravel.

But in my first week there, it was all about Rinpoche. I remember the first event as if it happened yesterday. A crowd of about a hundred Woodstock hippies showed up for the first talk. the first question, from real burnout who could barely articulate his thoughts, was, “Master Rinpoche, is it OK to get high?” He replied in broken English, “There’s nothing wrong with getting a little high, or a little low, or even a little sideways, if that is what you want to do.” Almost every question he was asked received a reply that ended with the exact same words: “…if that is what you want to do.”

He seemed to be okay with everything. I liked that. Very Zen. He was also definitely pursuing each and every female at the school. Very Zen. He had guards in the hallways outside the rooms of whomever he was involved with. The guard’s duties included keeping Rinpoche’s Tibetan terriers quiet, and keeping people like me who lived in an adjacent room from entering the hallway.

If you want to know more about the real Rinpoche, the best account I’m aware of is a little pamphlet by Ed Sanders called “The Party.” By sunset every night, this man was drunk as a skunk. Every night. He also had a thing for fast cars, and it wasn’t too long after my experiences with him that he got drunk, jumped into a sports car and summarily drove straight into a tree that refused to move when he hit it. He never fully recovered, and he was dead at forty-eight. Then they pickled him. Absolute Zen-ness.

Karl Berger taught me everything, and he did it through a kaleidoscope of contradictions. Also very Zen. It was fun to wake up each day wondering what would come pouring out of the infinitely gentle soul that was and still is Karl Berger.

One of the first things I remember him saying to me was, “Mark, music is in the air. it’s all around us all the time. It’s not hard to create. You just gotta reach out and grab it.” The very next day, he’d say, “You know, it’s not like music is just floating around and all you have to do is pluck it out of the air. Music is inside of us, and you have to dig deep to find it.” That same evening, after a few glasses of wine, he might say, “Well, you know something? Lemme tell you. There’s nothing to know. Nothing to understand. Nothing is what it’s all about. Look around you. See? Nothing!”

Then he’d offer that beautifully infectious laugh, and I was smitten for life.

Karl was, and still is (for some cryptic reason I’m hoping will forever remain a mystery), the kind of man you can’t help but listen to. And if you can listen, you can learn. I learned a great deal from many great musicians, but Karl Berger was the only one I’d call My Teacher. He taught me how to listen, not just to how the music sounded, but to what it is.

Karl taught me how to be the music I was playing, and how to create honestly, the way a great actor becomes the part he is playing by playing it as himself. There is a psychology to all types of performance, and it’s a hard thing to teach. Karl could teach. I clearly recall the moment I realized that this man was going to change my life.

I was an award-winning classical organist as a kid, and upon arrival at CMS, I could still play some of the stuff I had to learn to win those awards. At the first evening class, in front of all the other new arrivals, Karl asked me to play something from my classical repertoire. Thinking it’d be funny (no one laughed), I sat at the grand piano and played the so-called Minute Waltz. I played it perfectly. Fluid, seamless, uncorrupted by arrogance, no showing off. I just played it straight. Straight and proper. Just how I’d learned it. Just how it was supposed to be played.

Karl said, “That’s great. Now play it for me slower.”

I couldn’t do it. I stopped and started and started and stopped and re-started but no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t play that stupid little exercise slower than I’d rehearsed it and learned it.

“See?” said Karl.

If you’re really lucky, shit like this happens to you at eighteen years old, and you learn something. You learn quickly. Very quickly. After you’ve spent literally half your childhood practicing to play something at the “correct” speed, and you find yourself utterly incapable of playing it even a tiny bit it slower, you learn, among so many other things, that the true and honest value of doing something exactly the way it’s supposed to be done, is nil. You learn that life is full of invisible prisons and if you’re not careful, music can be one of them. You learn that child abuse comes in many forms, and that some of them can steal into your dreams disguised as education.

Other revelations came much slower, but that one hit me hard. It was an armor-piercing bullet slicing through the icy steel of classical training.

No one taught me more than Dr. Karl Hans Berger, who grew up in The Black Forest, and flew to the USA via Heidelberg, under the wings of Don Cherry, who must have seemed to Karl an angel, way back in the early sixties, when jazz was still king.

I almost forgot to mention: Ornette never showed his face there. Not even once. I was later told that he’d never even been there. He just allowed Karl to use his name, to get some added attention. And would I have gone there, if Ornette’s name hadn’t been in the ad? Probably not. Would the late great Ralph Carney and hundreds of other budding musicians I met there have ever sent in an application and a check and arrived all starry-eyed and ready to take over the world, had not Ornette’s name provided the inspiration? I can only speak for myself. But I do remember a common utterance up at that smoky lodge. “Where the fuck is Ornette?”

I stayed at CMS on and off for about two years between 1977 and 1979 and left for good when I joined Gong. Not long before I left, just before Christmas, Karl approached me. “We have to go to NYC and bring Ornette some firewood. You’re coming.” An hour later, Tom Cora and I were loading firewood into the back of his little Datsun truck. Karl and his wife Ingrid loaded themselves into their little car. “You just follow us. But don’t lose us. Stay close, okay?”

Tom’s truck was too heavy with all that wood in it. I doubt it had ever carried anything heavier than a cello before. Soon we were hurtling down the NY Thruway trying to keep up with Karl. Trying to stay close, like he said. Two hours later we were parking in front of an old tenement building on The Bowery. Karl banged on the door. “He’s on the top floor so this may take a minute.”

We heard footsteps coming down the stairs, getting louder and louder. the door swung open. Ornette Coleman. grinning from ear to ear. This i will never forget.

It took about ninety minutes for Tom and I to haul a full cord of wood up four flights of stairs and stack it all neatly against a brick wall not too far from a huge wood burning stove. There were paintings everywhere. I stood in front of one of them and just stared. Ornette walked up to me. “You dig?”

I looked him in the eye. “You painted this.”

“I painted all these. I’m just painting these days. I ain’t gonna sell ’em. I just paint ’em. This one ain’t finished yet.”

“This painting looks like it starts at the bottom and goes up.”

He stared at me. I was just a kid, and Ornette was staring me right in the eye. I guess I must have seemed calm enough on the outside, but inside, I was shaking like an earthquake.

“That’s right,” he said. “That’s it. You got it. You start way down there, and you work your way up. That’s how everything’s done. That’s the way of the world.”

We talked for about twenty minutes, about painting. Just painting. I didn’t know jack shit about painting yet, but he talked to me anyway. The subject of music never came up. The phone rang. Ornette picked it up, and listened. “Yeah? Okay. No. I said no. No, no, no. Okay, I’m hanging up now.”

He walked back over to me, shaking his head. “Some asshole wants to talk to me about music.”

A few months ago, Karl and Ingrid played a house concert at Jim Quinlan’s home in Miami Beach. About twelve people attended. I hadn’t seen Karl in thirty-seven years. He hadn’t changed even a bit. A few more circles under his eyes, perhaps. maybe a few more older ones hidden below the new ones. But aside from having added a daily mid-afternoon nap to his regimen, he seemed unchanged. His eyes sparkled as they did the day we met. The skip in his step was still there, and the flip-flops on his feet, the loosely-fitting aging-hippie pants and shirt, the way he really meant it when he gave you a hug. All there, still, unperturbed by time, undeterred by the 24/7 crusade to keep CMS alive, unwearied by a never ending parade of gigs that paid little, or didn’t pay at all. Loved forever unto eternity by each and every one of the thousands of students he’d touched, made whole, and sent out into the world a better musician, a better listener, a better human being.

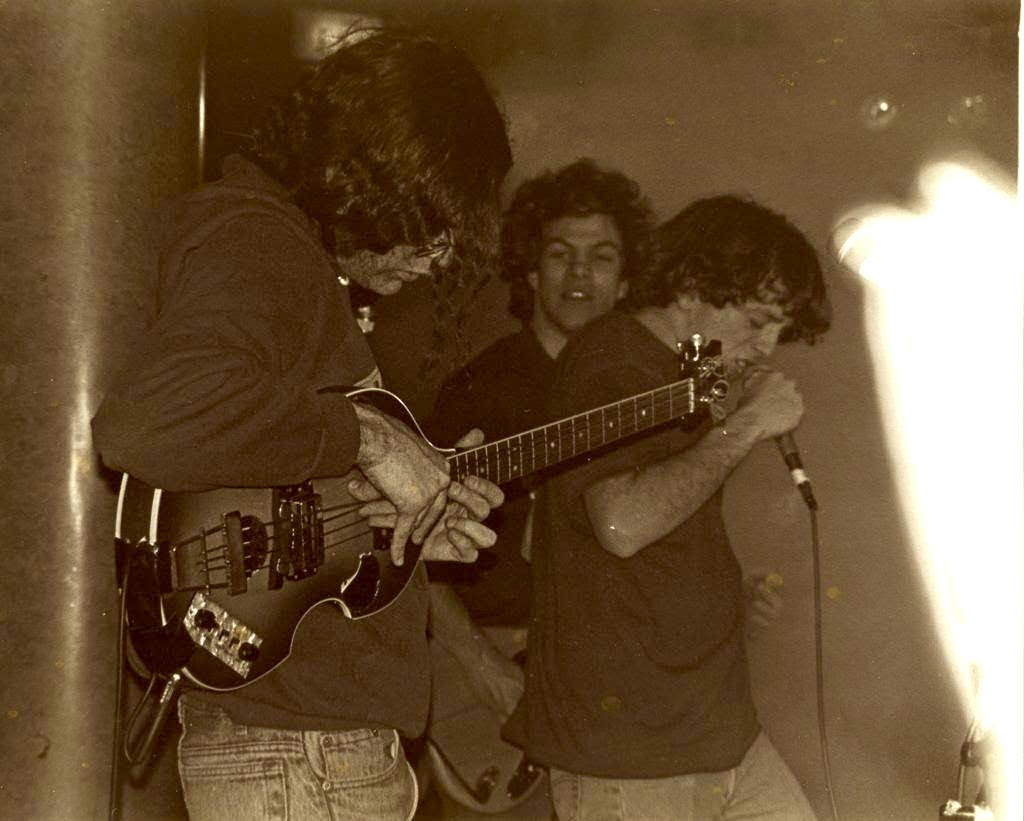

QUESTION #3:How did you meet Butthole Surfers, and what was it like touring with them? Did that kind of improvised open-ended psychedelia seem consistent with your background in jazz?

KRAMER: The best years of my life happened over the course of about six months in 1985 while I was on the road with Paul Leary, Gibby Haynes, King Coffey, and Teresa Taylor, collectively known as Butthole Surfers. I played a strapless Hofner bass guitar with them until I nearly died of food poisoning after a gig, somewhere in the bowels of the American Midwest. I am spared the memory of the exact location. Ohio, perhaps? What’s the difference where? Food poisoning or not, I had no choice but to leave them. I had other plans. I had just bought my first recording studio, Noise New York, and I wanted to live in it and run it and become a great engineer and a great producer and a great musician. Sometimes shit just doesn’t go where you hope and dream it might.

Paul was the most unhappy when I left. I’m not sure anyone else in the band really noticed. “Well fucking thank you, Kramer. Fucking thanks a lot. I guess we’ll just have to fucking find another fucking asshole bass player for a few fucking months until he fucking quits and then we’ll just have to do this shit all over again and go look for another fucking asshole bass player until I just fucking quit this stupid fucking band.”

I felt terrible.

But it was just weeks later that they married up with a killer bassist who finally glued it all together—Jeff Pinkus—who was but a boy when I met him at The Peppermint Lounge for the band’s first NYC gig following my departure in 1985. I think it must have been early 1986. I walked right up to him in the dressing room before the show.

“You’re Jeff. I need to thank you for saving my life by replacing me in this fucking band.”

We shook hands.

“Kramer. Wow. Took guts to come down here tonight.”

I replied quickly. “Nope. Took a taxi.”

I may die penniless, but thanks in great part to Gibby and Paul, these two Texas gentlemen who named their band Butthole Surfers and still got a major label record deal, I am, at least in terms of life experience, one of the richest men in the world.

I played with them on their debut European tour in 1985, and some of the most memorable stuff came within the borders of what is now a reeking repository of snow-covered sin that calls itself Norway. Many Butthole stories of legend were born in The Netherlands and have been told and re-told by myself and others. Books abound.

But strange and beautiful things happened in Norway, too, and I survive to tell.

Entering Norway from Denmark by overnight train requires a ferry ride. The ferry had train rails in its belly. The train drives straight onto the ferry’s nose as if it were just another lorry. at journey’s end, it then drives straight off the ass-end and into a depot filled with tracks spidering out in all directions. At least that’s how I recall it, as it was in 1985.

As this ferry approaches Norway, a voice cracks from the public address system onboard, first in Norwegian, I assumed, then in Danish, I’m pretty sure, and then finally in near-perfect English. I’m paraphrasing, but the following was the gist of it:

“Hallo. This is your Captain or pilot speaking now. We are now approaching the final destination and the terminal where you will now disembark and experience very soon the courtesy of Norwegian Customs & Immigration. Good Luck. We hope you enjoyed your journey. Good Morning. Please now proceed directly to your cars or your bus or to your train immediately now and please drive safely when you disembark. Thank you now.”

I had hung with Paul for most of the ferry trip. I always hung with Paul. Gibby was usually within visual contact, but at this moment we had no idea where he was, and King and Teresa as well had been conspicuously MIA throughout the journey. Eventually I found Ms T. curled up under the back of a table in the dining room, hiding behind a backpack, ashen and seasick. Gibby miraculously appeared out of nowhere just as we marched in place alongside hundreds of other passengers like standing sardines shuffling toward a tiny door that gave entrance to a skinny stairway leading down into the lower-most level of the ferry’s colon that would soon be shitting out the trains, cars, busses, etc. King had still not manifested himself, and Paul and I had begun to worry. There were no days without worry.

One of the immigration officers appeared at the window of our compartment. He stared through the glass at each of us, one by one. He looked up at our guitars and backpacks hanging precariously from the luggage racks. He looked back down at us. He smiled. He turned and looked down the hallway at someone and beckoned toward to him with that universal nod:“You think you’ve seen everything, well come see this.”

Two other officers soon appeared. After a brief through-the-looking-glass review of the contents of our little cubicle, they enjoyed a long and hearty laugh before heaving the glass doors open and confronting us, at which point they were suddenly as serious as cancer. One of them opened his mouth and some sounds came out. I waited for a sound reminiscent of the word “passport,” but heard nothing even close.

“English?” I asked.

Another man behind a badge opened his mouth and spoke perfect English.

“English? You now want us to speak English to you? That now depends. Will you ask us politely? Is ‘English’ the only word you will know in English? Are you going to behave now like civilized people when you talk to us? Because I will tell you right now, you don’t look very civilized to me.”

He was right. We looked like Hell had just puked us up and wanted no part of us. We looked exactly like what we were; a poverty-stricken American band with little or no idea of where we’d just been, where we were going, what we were doing, or why. It was all about surviving those twenty-three hours a day leading up to that one hour onstage. Onstage, we were a force to be reckoned with. Offstage, we were masters of nothing. And we looked it.

Except for Gibby.

Gibby was a twenty-four-hour-a-day Colossus. Like Richard Pryor running down the street on fire, people got out of his way. I’m reminded of one particular guy at the club that night in Oslo who for some ill-conceived reason had made a conscious decision not to get out of Gibby’s way, just before showtime. He had been taunting the band with steadily increasing levels of verbal abuse in both English and Norwegian since early evening, and soon he became the sad recipient of the most monstrously massive gob of Gibby’s mucous I’d ever seen conjured up. It landed dead-center on the guy’s forehead. Gibby doesn’t miss. The guy couldn’t even move. He just sat there at his table, his Norwegian beer in his hand, with Gibby’s massive loogie dripping down his face. People looked the other way, as if nothing had happened. It was surreal.

But I’ll get back to the Oslo gig later. I haven’t finished the Immigration story.

“I’m sorry,” I said to the Immigration officer who had just questioned my tone.

“We haven’t slept. We’ve been on this train and on the ferry since late last night after a gig, and we’re on our way to a gig tonight in Oslo, and we’ve lost our drummer. Well, one of our drummers.”

“One of your drummers? What does that mean now?”

“Well, we have two.”

“Two drummers. Why do you need two drummers?”

That got Gibby’s attention. He farted loudly. And that got the Immigration officer’s attention.

“I can now tell that you are musicians. I can also tell that you are not playing the music of Sibelius.”

Paul kept staring out the window. Gibby stared at the Immigration officer, who soon broke the silence.

”And you now. You don’t say anything. You only fart now. Do you do that at home?

Do you have a home? Do you have anything you want to say? Any words? In English, now?”

Gibby inhaled deeply, looked out the window, and replied, “I’ll say anything you want me to say.”

The big cheese spoke to Paul. “And you? You don’t speak?”

Paul looked up at him, and then at me. An expression of complete loss came over him. It was as if his soul had finally had enough of him, and taken flight.

He looked up at the big cheese, and then back at me again. He shook his head no, and joined Gibby in staring out the window. He never uttered a sound. The customs officer looked down at him and smiled.

“Okay, now we understand each other. Let me see your passports and your work permits.”

No one ever looked at Teresa or addressed her in any way. It was as if she wasn’t even there. This was not unusual for her. Perhaps they took mercy on her, seeing the state of her travel companions.

Three Immigrations officers examined all of our papers. Fifteen minutes passed before another word was uttered. Finally, the big cheese with the big head spoke again. “These work permits say very clearly to us that there are five people in your band. Where is this invisible fifth person now?”

Gibby and Paul ignored the question and kept staring out the window. Suddenly, they both shot to their feet. Paul swung the window open and started screaming:

”King! Over here! What the fuck! Where the fuck have you been? Over here! Over here!”

The Immigration officers responded as one would expect them to. ”Hey! Stop! You cannot do that now! Whoever is on the train now is on the train and whoever is off the train is not on the train! No one can enter the train now! No one is getting on this train! The doors are all locked now!”

Within seconds, Gibby and Paul were hauling King up through the barely King-sized slit in the window as the Immigration officers stare on in disbelief. One of them barked at us:“You cannot do that! Stop now! I’m telling you to stop! Hallo? I am speaking English now! Why do you not stop?! I am speaking now!”

In the confusion, I’m able to strike up a friendly discourse with the one officer I deem youthful enough to approach this crisis in a friendly manner and within a few minutes I’ve managed to diffuse the situation, but the focus is now on King.

“Okay, Okay! Let’s see your passport! Right now!”

Just as I think we’ve actually gotten away with at least one Norwegian misdemeanor, a new big cheese officer appears. He exchanges words with another officer. Moments later, each of us is subjected to an invasive pat-down, followed by a complete search of the train compartment. They do not find the half-ounce of hash hidden in my hollow-body Hofner bass guitar. Nor do they find the bag full of LSD tabs the rest of the band eats breakfast from every morning, and at this point, I’m starting to imagine that the remote possibility of making the gig that night was now becoming just a little bit less remote. Minutes later it seems not so remote at all, as the crew of officers gather themselves together and file out.

“Have a nice gig,” one of them says as they slide the door closed.

I look at Gibby and Paul. As they stare back at me with misery and unbridled hate, the message on their faces is as clear as the crystal waters of the fiords; less than one hour after entering Norway, they have had enough of Norway, and more than enough of Norwegians, and they would be venting their unfettered rage that evening at the hosting venue, the patrons of which I was already feeling sorry for. I saw all of this promise of forthcoming terror in the depths of their two faces, and the expressions therein would not change again until they were replaced by ones of sadistic joy after the show, after a few hundred Norwegians had been sufficiently subjected to the appropriately measured degree of contempt that, in Gibby’s and Pauls’ minds, this entire nation of alcoholics so thoroughly and richly deserved.

A few hours later, Gibby is sharpening his fangs as we enter the club for a soundcheck conducted by a middle-aged man hiding under a mohawk who seems to wish he was anywhere else on earth, rather than unrolling mic cables at an Oslo music venue. We treat him kindly, as we would any sound man, indeed as we would treat anyone responsible for controlling what the audience would hear a couple of hours later. In return, he treats us as most American sound men would treat us; he ignores us completely. I ask the club owner if the sound man can speak English.

“Yes, of course he speaks English”.

“Okay then. Is he deaf?”

“He has been here for many years now,” the club owner tells me.

“Too many, perhaps?”

“No one understands him. He is Swedish, but I like him very much anyway. And also he loves your band. He tells me he is very anxious to see the show, and that has all of your records.”

“Really? Both of them?”

[In 1985, only the “PCPP EP” and “Psychic, Powerless…” had been released]

“He has told me that he has all ten of your records.”

“We only have two. Believe me.”

“Well, then maybe he is now dreaming. The Swedes are big dreamers. But he is a good sound man. People don’t give him a chance. They see his mohawk and they think he must be an asshole. Many Swedes are assholes but he is not an asshole. You must give him a chance.”

People are milling around the venue before we begin soundcheck, in increasing numbers. I see someone taking tickets at the door, and I inquire;

“Hey. Can we do the sound check before they let people in?”

“No.”

“No?”

“No. That is not our way to do things here now. This is Norway and it is very cold and we don’t let people to freeze outside if they have a ticket. If they can show us that they bought a ticket they can come in now. That is customary here. It has always been this way, ever since—”

“Okay, whatever. Thanks.”

I walk back to the sound man and try to strike up a constructive conversation. For a few moments, I thought I was going to succeed.

“Hey. I’m Kramer.”

“Hallo. Yes.”

“You’re the sound man, right?”

“Yes. Tonight it is me who is your sound man. Yes.”

“Can I talk to you for just a minute or two about the sound?”

“No.”

“No? You won’t talk to me about the sound at our gig tonight?”

“What? Oh, yes, you can talk to me now and I will try to answer you.”

“Okay, well, my name is Kramer.”

We shake hands.

“I am Smellen. actually my name is Lars, but here in Norway, they call me Smellen. you can call me Smellen.”

“Are you absolutely sure you want me to call you Smellen? Because I can easily call you Lars.”

“I am Swedish. I don’t give a fuck what you call me. I am in Norway now. I just do my job and go home.”

“Okay, well, can we get some kick drum in the monitor?”

“No.”

“No?”

“No. Nothing can go into the monitor except vocals, because the band here last weekend completely destroyed the monitors, so we now had to…”

It went on like this for a few more minutes before I gave up.

During the show all hell broke loose when a guy flicked a lit cigarette onto one of Teresa’s floor toms. I will never forget this. She picked the cigarette off the drum skin and looked around the audience. As if by psychic powers, she instantly knows who flicked it. She gingerly placed the stub between her thumb and middle fingers and flicked it toward the man’s face. It hit his cheek and stuck there, via the marriage of burning tobacco and human skin. The man slapped his face repeatedly until the last burning embers fly off. People around him scatter. He immediately charges the stage, but the crowd is so animated, he can’t reach us. This enraged him to the point of insanity. Half the audience witnesses this drama and they love it. We own this crowd. It is an unforgettable moment.

In the dressing room after the show, Paul asked Teresa: “Why was that guy trying to kill you? What did you do to him?”

“I showed him my titties,” she replied.

Suddenly the same guy bursts through the dressing room door. He has a huge burn mark on his cheek, and he is smiling from ear to ear. I have not seen anyone this happy since the tour began. He clears his throat twice before speaking.

“That was the greatest show I have ever seen in my life.”

Gibby replied, “Oh yeah? Well, fuck your ass and fuck your ass again and then you can suck my balls, asshole.”

I’m not sure whether or not Gibby knew that this was a guy who was trying to kill Teresa in the middle of the show. I’m also not sure if his reply would have been any different had he known. Stuff like this didn’t matter much to Gibby. Or they mattered more than anything else in the world. One never knew how Gibby might respond to any stimuli. It all depended upon how much sleep he hadn’t had, how much (or how little) hard liquor he’d drank just prior to going onstage, how much LSD was dripping from his eyeballs at that particular moment, and any number of other factors most civilized humans should never imagine. The very thought of knowing the mind of Gibson Jerome Haynes for even a microsecond was a thought better left unthunk. He was a walking, talking X-factor that could blow up in our faces at any moment, and often did. Of the ten or so times in my nearly sixty years that I have witnessed my life flashing before my eyes, Gibby was right there for eight or nine of them.

Afterward, the club owner tells me that he has been running this club since it opened and even though it has the reputation for being “the most dangerous and violent venue in Oslo,” he has never seen anything like what he saw tonight.

“The crowd really outdid themselves now. We have the same people come here almost every night, behaving very badly. Usually. they are frightening the bands very much, but tonight it is the other way around. I am very proud of them. The way they let you take over. It was very good tonight. I will have a free matinee show for them tomorrow with my own band. I am anxious to see how soon they go back to being normal now. I hope you have not ruined them for life. Your band was very good. You must come back soon now.”

A bartender interrupts; “Hallo. You have now two people in your band fighting in the dressing room.”

I rush to the dressing room and find Paul smashing his vintage Fender Telecaster against the ground. He then gets down on his knees and starts beating it with his right fist. Blood begins to spurt forth. Gibby watches silently, with no expression on his face. A small crowd is gathering at the dressing room door. Smellen, who seems to have perked up a bit following the show, pushes his way in and walks right up to Paul. He leans down and says: “I love your music. I have all of your LPs.”

Paul stops beating the shit out of his guitar and looks up at him.

“What the fuck are you talking about?” he says.

“Nothing,” says Smellen. He hangs his head low, turns, and slowly walks away. We watch him as he shuffles off. He does not turn back for a final glance. He is gone. Smellen.

Soon the band is packed up and prepared to catch an overnight train to Stavanger, where unbeknownst to us all, an all-new, all-fresh Hell was awaiting us.

Perhaps a bit of backstory might assist in understanding how we got to where we were about to find ourselves; I was booking the tour pretty much on my own, with the help of a small agency in The Netherlands. I’d had been told that this Stavanger show was “a college gig” for “big money that would pay the expenses for all the other gigs in Norway,” but upon arrival, we found ourselves inside a vast gymnasium buried on some sterile campus, face to face with a group of upper-class “students” in suits and ties who had arrived early to “welcome the band.” I’m told by a student rep that they had just attended a graduation ceremony for a prestigious oil company’s private engineering school for the sons and daughters of the oil industry, and that not most but all of the graduates will now directly enter said Norwegian oil industry, of which Stavanger is ground zero. I think about this for a few moments and recall looking out the train window earlier in the day. There were oil rigs dotting the gray-blue line where the autumn sky licked the sea. Lots and lots of oil rigs. Some seemed close enough to swim to. It just wasn’t right. There was something terribly wrong with this picture, and I should have sensed it.

It was all beginning to make sense to me now. It was suddenly so clear I could see the future, and I could see that the most immediate parts of that future racing towards me were going to be very, very difficult.

The newly-minted graduates are filing into the auditorium now. Nearly all are wearing suits and ties. Some look as though they had just arrived from a day in church. Many of the women could easily have just walked out of a Norwegian Norman Rockwell painting. They are positively as pure as the Norwegian snow. If any of these kids is in the least bit interested in music, it would not be Butthole Surfers music. It would be Duran Duran, Flock of Seagulls, or WHAM!

A DJ is setting up in the back corner of the auditorium. As we begin loading out gear onto a collapsible stage that seems destined to collapse, the DJ tests his sound system by spinning his first song: “The Safety Dance,” by Men Without Hats.

Paul is standing beside me, moaning, “Oh no. No, no, no. Please dear fucking Christ tell me this is not really happening to me.”

He walks off the stage and into the dressing room. He is openly despondent.

The “promoter” introduces himself to me with his chest puffed out in pride. He tells me that he has hired “the most experimental DJ now working in Stavanger. He is now always doing unexpected things. Some people love him but many people hate him because he is so controversial. I knew he would be the perfect DJ for your show. He is actually Swedish. His name is—”

I interrupt him as fast as I can; “Please. No. Don’t tell me.”

Gibby approaches me, smiling.

“Hey Kramer. guess what I just ate 6 tabs of very powerful LSD. Whaddaya think?”

Here we go, I thought.

I look around for the sound man. I see no sound man, and no mixing console.

I inquire as to their whereabouts.

“Sound man? We were not told that you are needing a sound man.”

“Okay, well, where’s the sound? I mean, where’s the P.A.?”

“Well, if there is no sound man then we assumed you do not need a P.A.”

My heart sinks.

I hear Paul screaming my name. I follow the sound to the dressing room.

“Kramer, where’s the fucking acid?”

“What? How the fuck should I know where the acid is. Ask Gibby.”

A combination or deep sorrow and infinite wrath sweeps across is face.

“Why should I ask Gibby?”

“Listen,” I said. “I’ve got nothing to do with this. Talk to Gibby.”

“Did Gibby eat all the acid? That fucking asshole! I hate this stupid fucking band!

I told you I hate this fucking stupid band and I fucking meant it. I quit! I fucking quit!”

He charges out of the dressing room and comes face to face with Gibby.

“Did you eat all the acid, you dumb fuck? I hate you. ”

Gibby ignores him at first, but then has a better idea. He puts his nose a few inches from Paul’s face, and oh so quietly, he begins to sing, in almost a whisper.

“I see a little silhouetto of a man…”

Paul’s face turns bright red. He turns and rushes back into the dressing room as Gibby gives chase, taunting him: “Thunderbolt and Lightning! Very, very frightening!”

Paul slams the door shut before Gibby can get in. Gibby shrugs and turns back toward the expanding throng. He is watching the suits file in and licking his chops.

“Gibby wants red meat tonight,” he says to me.

I hear the now all-too-familiar sound of breaking glass coming from behind the dressing room door. I rush toward it and burst in. Paul is smashing unopened beer bottles against another Vintage Fender guitar. This technique opens the bottles very quickly. In musical step with each Nolan Ryan pitch of each bottle, Paul’s face gets redder and redder. He croons as he smashes each bottle: “I. Fucking. Quit. This. Stupid. Band. I. Fucking. Quit. This. Stupid. Band. I. Fucking Quit. This. Stupid. Band…”

Gibby walks in and takes his standard position, back against the wall not far from the shattering glass, completely calm. He is watching Paul’s tantrum the same way one patron at Starbucks watches another sip coffee, with a thoroughly detached indifference to something he sees so often it means less than nothing to him.

You get the picture. I saw this picture nearly every night, along with a good cartoon before the main feature, and as many truly horrifying coming attractions as I could watch. In just a few months with this great band, my capacity for the direct witnessing of this kind of ”acting out” had become almost limitless, and I was fast turning numb to it. I could easily have joined in, just for fun, but… I don’t know. Maybe I thought I hadn’t been in the band long enough yet. I only know what I saw.

An hour later, the gymnasium is packed solid with future oil company executives dressed in their Sunday best. This will not end well. The show begins (as usual) with a cacophonous howling of drums. I mount the stage with my bass guitar and as I plug it into the amp, I see Gibby crouched behind it in a polka dot dress, his hair a mass of clothespins, his face smeared with red lipstick. Clenched in his left fist like a grenade is a bottle marked “flammable.” In his right hand is a Bic lighter. He looks me in the eye. He is not smiling. I am afraid.

I take a few steps back. He holds his fist up toward me with his middle finger fully erect, pours the liquid all over his right hand, sets it ablaze, and charges out from behind the amp toward this shamelessly peaceful gathering of upper-class Norwegian kids who have never in their wildest dreams imagined that on the same evening they graduated from university, they would be the targets of a psychotic Texan hell-bent on educating them on the subtle intricacies of what it really feels like to be confronted by the spectre of a human fire hazard racing toward them with burning death in his eyes. Gibby is already well over six feet tall, but in the eyes of these unsuspecting students—some already appropriately aghast and running for the exit doors while others are clearly frozen by terror and fear—he has now rendered himself as tall as a volcano and as unforgettable as a plague of flaming harpies. Some adults in the back of the room stare on, frozen in shock. They cannot move.

Just to help you keep track of time here, we are, at this point, about thirty seconds into the show.

There is one exit, conveniently centered on the back wall a few feet away from the DJ. Having failed in his repeated attempts to set on fire even a single Norwegian who had paid the equivalent of about $7 for a ticket to a show at which she could easily have been carted out on a stretcher with 3rd degree burns over 80% of her body, an enraged Gibby clamors back onstage and runs behind Paul’s guitar amp, only to emerge a few seconds later with a large plastic box which I immediately recognize as a case of breakaway bottles we’d been lugging around Europe for weeks, waiting for just the right occasion. It appeared clear to me that Gibby had just spontaneously decided that this was precisely that occasion.

(Note to the uninitiated reader: breakaway bottles look like real bottles, but they are actually props made of sugar to be used in theater, film, the circus, etc… you can smash them against someone’s face and no one gets hurt.)

But the Norwegians do not know this.

Gibby reaches into the box and stuffs as many bottles into his arms and under his armpits as he can, at which point the few Norwegians who had chosen to wait and see what he might do next were deciding that they had seen enough, and briskly joining the mad rush to the exit door. Inspired by the sight of screaming people running away from him, Gibby begins heaving one breakaway bottle after another onto the wall at the back of the room, directly above the exit door, raining tiny bits of sugar down upon the heads of hundreds of hysterical students laboring under the mistaken belief that it was shards of glass falling on them. Within seconds the mass hysteria is magnified threefold. The screaming is getting incrementally louder, and one can hear the sound or crying mixed in. I look around for Paul. Where is Paul?

At this point, I am witness to something that looks more like a stampede at Mecca than like a rock and roll gig. A bottomless, aching fear was raking itself across every face in the crowd. It is quite possible that not one of these panicked students is not screaming, and the sound of the screams is louder than the pounding drums. It stabs and cuts into the night like a pogrom. Fear grips me.

The gig is now about ninety seconds old. It hasn’t even opened its eyes yet, and it gets better.

Paul suddenly appears onstage with his guitar.

He plugs it in, turns each dial on the amp up to 11, and lets the feedback roar. The sound is deafening. I cover my ears. He slams his vintage Fender Strat down onto the stage with all his strength and then viciously drop-kicks it like a football. It skips and skids like a spinning top past the drums and comes to a teetering halt just millimeters from where it would have tipped off the stage and gone crashing down to the floor.

Paul strides slowly across the stage like Frankenstein’s monster and picks up the guitar. It’s still screaming feedback. He walks to the edge of the stage, widens his eyes in a psychotic stare, tightens his lips over his teeth so that both his upper and lower rows are visible, and makes a face that is 100% identical to the face King Kong makes in the original 1932 film version when he first lays eyes on Faye Wray. I recognized it immediately.

He drops his pants, and plays the opening licks from “Cowboy Bob” for a few seconds before jettisoning it and letting the howling feedback return. It was the right thing to do, I thought to myself. I put my fingers into my ears.

Paul is now stark naked between his ankles and his t-shirt. His penis is unanimously flaccid, and I am no longer afraid. I am no longer afraid of anything. Fear has been rendered meaningless in the face of what I am now seeing, if in fact I was actually seeing it. As with so very many things I’d witnessed since joining the band, it was difficult to be absolutely sure.

The sound of humans screaming is getting louder. It is louder than the screeching of Paul’s guitar. He leans the guitar against a floor monitor and suddenly the decibel level begins to resemble that of a 747 taxiing down the runway for takeoff. I put my fingers deeper into my ears, but it makes no discernible difference.

The sight of Paul’s unaroused penis was enough to spark wild activity in the back of the room among the “adults.” An older man whom I presumed to be a “teacher” now rushes to the front of the stage and looks around for someone to confront. He sees me crouching beside my bass amp, climbs onto the stage, and makes a bee-line in my direction. My fingers are still plugged into my ears to protect them from the deafening decibel levels of the combined sounds of screams alongside Paul’s howling feedback and the throbbing drums of King and Teresa, which by the way have gone on uninterrupted since they picked up their drumsticks a few minutes prior. A relentless beating that seemed to say “This will never end,” a violent, thundering motif inciting of a purgatorial playground that seemed to say, “You people will hear the resplendence of this ravaging sound for the rest of your pitiful, pointless lives, even if you someday go deaf.”

The man starts screaming at me.

“You must tell him now to pull his pants up! Tell him now! Now, please!”

I glance over at Paul. He is proudly sporting the same King Kong caricature, while displaying his penis, but suddenly, as I watch, he ramps up his game significantly. He has begun to play a guitar solo. A real guitar solo, as great as anything I’d heard him play before or since. It dissects the crowd like a thousand knives of glistening steel, forged in the combined nightmares of a few hundred Norwegian kids now fleeing in galvanized terror. It is beautiful. It is beyond beautiful. and I am in awe.

“Are you listening to me now?! Tell him to pull his pants up! Please! Now!”

Suddenly someone pulls the plug and the only sounds left are the ongoing acoustic assault of tom-toms, the screams of the few remaining kids who have yet to make their exits, and the last of Gibby’s breakaway bottles hitting the wall above their heads. The box finally emptied, he heaves it as hard as he can against the wall behind the drums, and tears his dress off. He is now in his birthday suit too. His penis, also wholly flaccid and far smaller than what one might expect of a man his height, has red lipstick all over it.

So, about three minutes into the show, we now have two fully exposed and flaccid penises onstage, two drummers pounding away as if their lives would be over if someone tried to make them stop, and the sound of approaching Norwegian police sirens slowly rising up above the din of the drums.

Gibby hears the sirens and he is gone in a flash. Literally. I blinked and he was gone. Paul is slower to hear the approaching sirens, but when he does, he turns off his guitar amp, and calmly pulls up his pants.

The “show” has begun and ended in the course of about four minutes, which was over twice as long as the one solitary gig I did in NYC as the bassist for GG Allin’s Superscum (Steve Shelly, Gerard Cosloy, and Thurston Moore were the other scum, as I recall). That one was over in about two minutes. Maybe less.

The room is dead silent as the police arrive. They look around, consult a few “adults” in the back of the room, and leave. This process takes about ninety seconds. I breathe a deep sigh of relief. I look around and I see no one I’d been traveling with for the last few weeks and months. I am the only Butthole Surfer in the room. People are glaring at me, and I am still not afraid, but I nevertheless retreat with haste to the dressing room, where I find Paul, silent but on the verge of tears, glaring murderously at Gibby, who is naked save a bottle of whiskey in one hand and a cigarette in the other. It is hard to discern where the bruises end and the smeared lipstick stains begin. There is death in the air. I leave quickly.

A scowling man approaches me and opens his mouth as if to speak, but he cannot. He turns to walk away, but then stops, returns, and positions himself before me. He reaches into his vest pocket, pulls out an envelope stuffed with Norwegian kroner, and forces it into my palm. Seemingly summoning every last ounce of fortitude in his possession, he speaks: