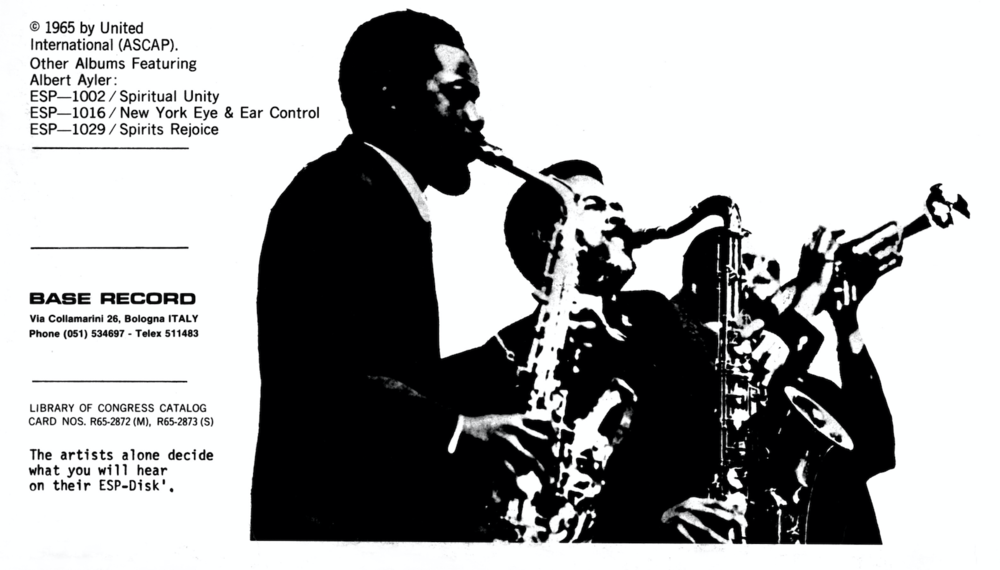

Detail from a promo copy of Albert Ayler’s Bells , courtesy Ayler.co.uk

Detail from a promo copy of Albert Ayler’s Bells , courtesy Ayler.co.uk

I. Night of the Senses

There are a couple of early snapshots of me and my father that I haven’t seen in years, thanks to my mother’s inexplicable embargo, in place for well over a decade, on the display or exhibition of family photos. These snapshots are black-and-white in the unselfconscious manner of 1963; I believe the date, not that I’d need it, is stamped on the border of each. In both, I’m sitting on my father’s lap in one of the raggedly covered armchairs I vaguely remember from our old apartment on E. 13th. In one, he’s bending toward me, no doubt telling me something; in the other he’s holding me balanced on his knee, and appears to be commenting to someone off to one side, invisibly beyond the lefthand frame of the picture. In both pictures my face displays the delight that I have always associated with being in my father’s presence.

My father rather famously loved jazz, particularly bebop and hard bop, though his interest extended well into the range inhabited by the likes of Albert Ayler (I can recall evenings when my mother lit out for the shelter of the bedroom as the transparent disk on which Ayler’s spooky Bells had been pressed rotated on the turntable in our living room). He listened to music every evening, at the end of his working day. On Friday nights—hamburger night, in my parents’ particular system of rituals—my father would stand guard at the entryway at the top of the stairs, the front door open to allow the greasy smoke to escape the apartment, with a cigarette and a bourbon over ice in his hands, the volume cranked so that the music banged up the narrow shaft containing the poured concrete steps of our apartment.

Among the many thousands of things my father told me—because in a sense his every action was a sort of enjoinment to me—was to love jazz too. Thelonious Monk was my favorite for a long time; through him I acquired a taste for dissonance, for the slightly skewed approach, that I’ve never lost. For a while I borrowed from my parents a 10” Monk LP with the irresistible title of Genius of Modern Music, and I would space out in my room listening repeatedly, in particular to the stupefying collaborations between Monk and Milt Jackson on cuts like “Epistrophy,” “I Mean You,” and “Evidence.” When I was around twelve, though, I decided to get some records of my own and I became the only kid at I.S.70 to go out and buy Thelonious in Action, a recording of the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in