If driving in Los Angeles is like reading Dante in the original Italian, as Reyner Banham claims in his Architecture of Four Ecologies, then walking in Los Angeles is like getting smacked with the extended text in the middle of a smog cloud. The city’s infrastructure was bent to service the private passenger automobile, and the industries that prop the thing up. The air is loud and thick outside a climate-controlled car, but it wasn’t until I walked in other cities that I realized how lonely, also, Los Angeles could be. Despite rush hour’s press, there are few strangers to nod by, or outfits to admire, or a general serendipity of location: you might be the only pedestrian for miles of these long streets. Even with the delicious spill of a convertible, everyone remains tucked away in machines. There are faces scrubbed cool on billboards, and shadows glancing past behind tinted windows, and nobody else, it might seem. Sometimes, I’d feel that I was walking through a future where giant metal beetles had overrun the desert, that I had to move carefully to avoid these creatures who communicated via red lights, bleats, and the occasional fleshy appendage thrust from a chrome exoskeleton.

Los Angeles does have a balm for this isolation. The movie theaters were there for when I felt especially detached. As much as the stories themselves, it was how the rooms carried the films that would make me feel like a person again. Faces on screen, big enough to see each emotion flicker across them, their voices shimmering the acoustics. Within the caramelized dark, other people were laughing and gasping and jumping in their seats, caught in the same swells.

This deep immersion in humanity informs Jess X Snow’s new documentary AFTEREARTH. Intended as a 3-channel video installation, the film can now be screened online as part of a Care Package series curated by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center. I hope to experience this work in person one day, but even without the accompanying channels, AFTEREARTH is enveloping. The piece stars Hina Wong-Kalu, Isabella Borgeson, Kayla Briët, and Wang-Ping Oshiro, all considering what they’d keep within “a time capsule if they could preserve it in a film” as Snow explained on a panel introducing the Care Package. Each artist is centered in one of the four elements, and the film expands within that structure as Snow’s camera spins around them. Facing the dual disasters of climate and white supremacy, the artists present songs, gardens, and poems that become “offering[s] to the earth”—promises alongside their activism that the future will keep going. From close-ups on electric eyeliner, to family photos held tenderly in the camera’s focus, to Borgeson’s pale dress gleaming in sunset, Snow situates the artists within time as much as the landscapes in this meditation on the necessity of care. That kind of immersion flows from Snow’s mural work as well. In their distinctive style, Snow centers collective healing and brings light to issues of environmental and racial justice with portraits of local activists and artists. The murals exist across the country, and you can find them collected on Snow’s Instagram.

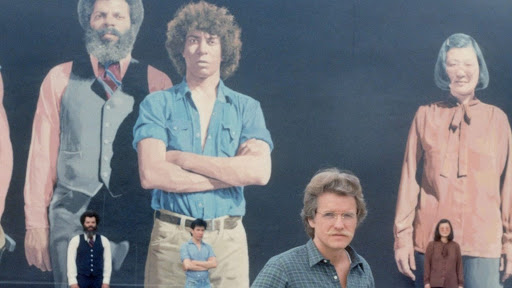

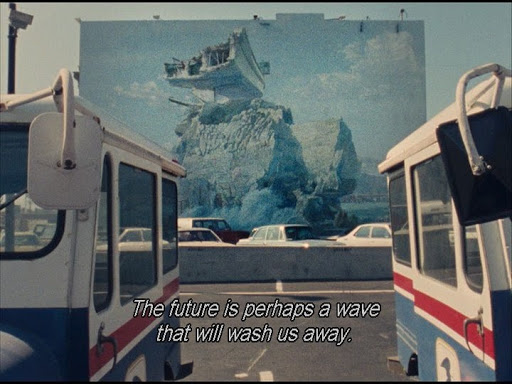

Public art presents a regenerative alternative to the hostile architecture and billboards of cities, as Agnes Varda points out in her 1980 documentary Mur Murs. Available for streaming on the Criterion Channel account I share with like eight people, Varda interviews muralists across Los Angeles, with ample shots sweeping down the paintings to let the walls talk. My favorite scenes are when the camera rests on a mural as little kids or roller skaters swirl around it, showing how the work exists within the neighborhood.

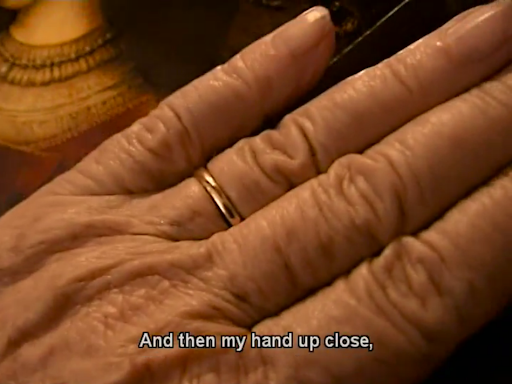

Mur Murs pairs well with Varda’s 2000 documentary, Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse (The Gleaners and I). This piece chronicles those who glean, or scavenge food and objects from both rural and urban regions of France. Varda’s interviews reach beyond sentimentality, and part of that intimacy comes from her technology. This film marks when the grand-maman of the French New Wave first picked up a digital camera. It certainly helped her travel more freely as an older woman for preliminary research, getting closer to people without a larger film crew in the way. The digital camera’s ease also made Varda more “involved as a filmmaker” in the piece, capturing herself in the footage as part of an implicit bargain: if she “was asking so much for these people to reveal themselves,” then she should act with the same vulnerability.

Some of my favorite recent cinematography comes from music videos. While I love a blown-out, sci-fi pop extravaganza, it’s been sweet to see music videos develop the gaze of a personal camera in the last few years. Cousin to the vlog, these videos are shot by the artist, often within their bedrooms. It’s almost the gaze of a younger sister, sprawled on the bed watching them get ready for the night. There’s Solange dancing through a scrapbook of private moments in “Binz”, and Daniela Andrade posing on another frame of herself for “Ayayai”.

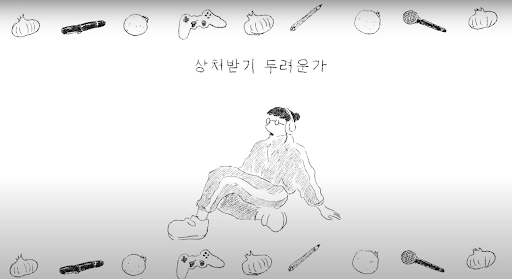

Music videos released in the last few months under quarantine have certainly furthered that Photo Booth Intimacy. The pieces incorporate more of a digital interface, like the switching FaceTime frames between Kiana Ledé and Ari Lennox in “Chocolate”. It’s odd to see a Haim video where the sisters aren’t strolling down LA streets in gorgeous defiance of traffic laws, but remote direction and choreography have created some cool, energetic dances for songs like “I Know Alone”. With studio shoots unavailable, other musicians have swum deep into their own archives. Road trip clips form Hayley Williams’s “Why We Ever,” the dates delicately positioned in a low corner. In general, archival footage can question what we might gather from the past that could be useful for our purposes now, in both art and living. A playful take on that would be the retro internet motifs in videos like “Damn Daniel” from Bree Runway and Young Baby Tate. Green screens connect the two while lasers, matrices, and 8-bit icons whirl across static and screens. It calls back to the nineties, just as Bree Runway has returned to the practices of an earlier phase in her career by styling and producing the song and video herself. Charli XCX also flourishes with cyberspace antics in “Claws”, the backgrounds and glitches growing more fantastical with each beat. Drawing on her visual art skills, Yaeji has gone fully animated with her latest pieces, with Luis Yang elaborating on her doodles for “WHEN I GROW UP.”

I think the themes of these videos with more immediate production—reckoning with digital life, personal cameras, deeper attention to the collective and individual past—forecast how feature films will integrate the pandemic. But under quarantine, what limits artists the most are not necessarily the boundaries of social distancing. Austerity and grief govern daily being on a mass scale, with actual governments more concerned to save stock markets than human lives. With so many more people using the internet to socialize and work, it’s necessary to consider personal security and wider surveillance risks.

The School for Poetic Computation is offering a range of classes at all levels to incorporate humanities teachings into technology. In particular, Dark Matters Expanded examines the racialized violence wrought by surveillance tech. While applications for the current class have closed, there will be future sessions, and many of the works from teachers American Artist and Zainab Aliyu are documented online in the meantime. For beginners to digital safety, the cybersecurity tutorials slash beauty reviews from artist Addie Wagenknecht will refresh the mind, and perhaps face. Her latest tutorial offers alternatives to Zoom, plus a tantalizing cat eye.

For other inspiration on how to adapt in spaces never intended for collective health, there is the new People’s City Council. In partnership with Black Lives Matter Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Tenants Union, and other local organizations, they’ve protested at the mansions of council members and the mayor with new tactics for this time. Lines of cars honk down a planned route, with posters covering each car to demand rent and eviction cancellation, and better housing for everybody in the city. It is the friendliest, most efficient traffic jam. The infrastructures of capital would keep us as individuals, caught in our own courses, unable to form alternatives to the problems we didn’t realize that we shared. Behind windows and masks, I know you are also here, your face lit by dreams of other worlds where we have the safety we deserve.