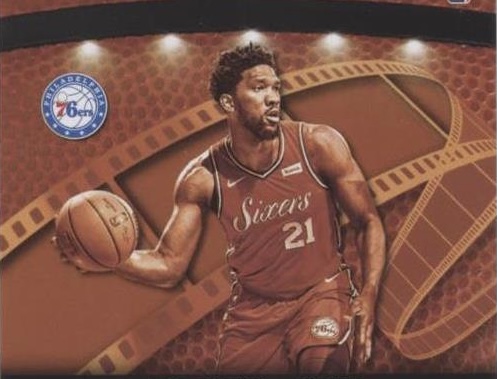

The best thing about sports fandom is the sensation of living in a feel-good movie, as storylines develop in real time. Watching the 2016 NBA finals felt like seeing an adaptation of Star Wars play out on network TV: the uber-talented, record-setting Warriors and their “Death Lineup” versus a scrappy Cavs team led by LeBron. Cheering one way or another was to impart one’s own force to their team of choice. The game’s mise-en-scene supports the cinematic aesthetic: the drama of a game seven; the triumphant orchestral score ABC uses for the finals; the distinct rewatchable sequence (the Block, the Shot, and the Stop); the fact that that series, and all NBA finals since 2003, have aired on the Disney-owned ABC, adds to this filmic sensibility. In America, our sports movies are often made by Disney, and they are usually either treacly and uplifting or gritty and inspirational (The Fish that Saved Pittsburgh, Hoosiers, The Air Up There, The Mighty Ducks, Space Jam, Love & Basketball, Miracle, Coach Carter, Draft Day, The Way Back). Only a few lend themselves to tragedy or cynicism (Brian’s Song, Blue Chips, The Basketball Diaries, He Got Game).

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in