There is a story told in my group of friends back home in the Bay Area that always makes me laugh. My friend, let’s call him Sam, was working as a well-compensated engineer at a technology company that makes software for other businesses. Sam is one of the smartest people I know. He’s talented at many things, and coding happens to be one of them. For him, his job is a job, one that affords him the ability to live in the inhospitably expensive city that he loves, the city where he grew up and where his family still resides.

One day his company sent out surveys to everyone trying to assess their job satisfaction. The executives came back to the employees after the surveys were tallied and reported back for the most part people were doing okay—except for one thing. People scored the “meaning” question relatively low. This surprised the CEO. He thought everyone who worked there found the work meaningful. Sam found this assumption hilarious. Why on earth would he think that?

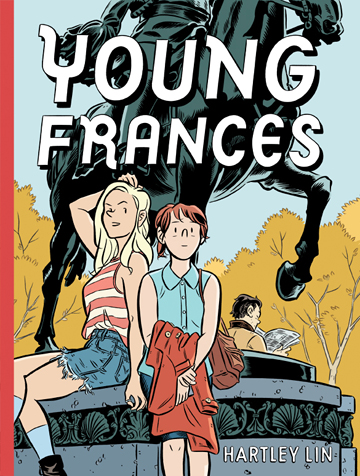

Who decided our jobs have to define who we are, and how we move through the world? That’s one of the central questions in Hartley Lin’s graphic novel Young Frances. The book itself is warm and funny and smart, careful not to stray too far beyond the bounds of realism. The story first appeared as serialized chapters, written under the pseudonym (and anagram) Ethan Rilly. Lin started writing it when he was still relatively new to the workforce, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. He was working as a public servant for the Ontario government, and was curious what people he went to school with were up to. “A lot of people I know… [were] just staying in jobs that obviously they had problems with,” explains Lin. “But who wants to look for a new job when there’s no jobs to be had?”

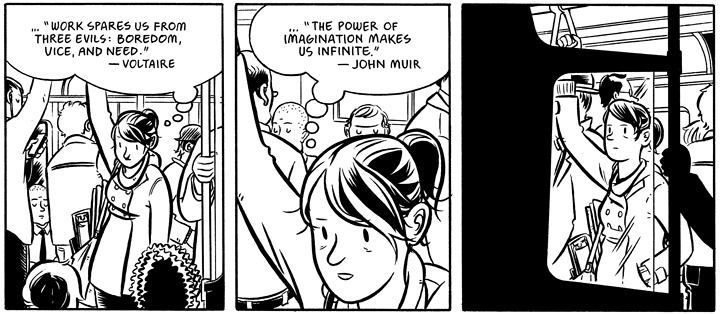

The protagonist of this novel, Frances, is a law clerk at a prestigious law firm. She’s talented at what she does. She works at the kind of cutthroat place where the lawyers count the tiles on the ceiling to see who has the bigger office. Everyone’s trying to get ahead—except for Frances. She stays above the fray of office politics. She’s not even sure she wants to work there. And yet, she’s very good at her job, and because of this, she’s soon noticed by the higher-ups, including a terrifying partner at the firm named Marcel Castonguay. Mr. Castonguay’s outsized presence is emphasized by the way Lin draws him. Mr. Castonguay could be mistaken for the Incredible Hulk. He’s massive, built like a block, towering over the others. He’s a mythological presence in the office. He doesn’t eat. He doesn’t ever take days off. He doesn’t own a coat or an umbrella because he lives in the hotel across the street, and can take the passageway in the underground mall to his office building. He’s the type of guy who would read blog posts about intermittent fasting, the four-hour-workweek, and how to steal the blood of younger men to reinvigorate his own. Basically, he’s a maniac.

Much of the novel is concerned with how Frances orbits around him and his outsized sense of power. But it’s also the story of her friendship with her best friend Vickie. Like Frances, Vickie is very talented. But it’s a different kind of talent—she’s fiercely charismatic. She’s an actress, destined for fame. In the course of the novel, Vickie is sent to Hollywood and lands a breakthrough role as a butt-kicking vigilante prosecutor in a new TV show. Frances and Vickie are incredibly close, but equally befuddled by the nature of each other’s careers. It’s the most obvious facet of their life that they can’t share. Vickie and Frances live together and depend on one another. And yet Frances is confounded by the kind of ridiculous pomp and circumstance involved in making Vickie a star, and Vickie can’t remember the names of anyone in Frances’ office, or why she should care about who is getting more billable hours. Their struggle to relate to one another speaks to how work can serve as a chasm in a friendship at that stage in your life when suddenly people are making decisions, decisions specific to themselves, and not everything can be shared. “Some inner insecurity will speak out and say like, don’t be too talented in that direction!” echoes Lin. “We need to be in the same boat.”

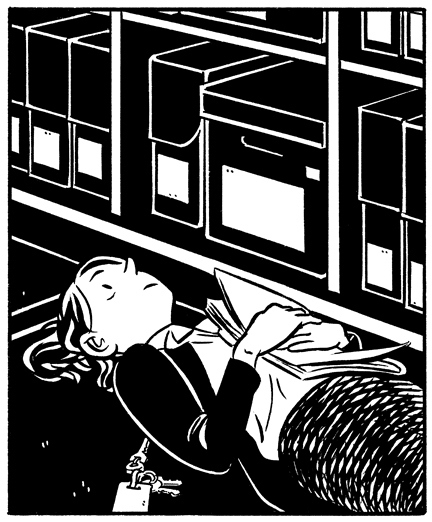

Vickie wants Frances to quit. She wants Frances to find a job that maybe would feel more fulfilling. The first time I read it, I was aware that I too really wanted Frances to quit her job. There was one moment when another door opens for her—another job offer, for what many might consider a dream job. It’s thousands of miles away from the office building Frances toils away in, the building where she often locks herself in an empty filing room just so she can lie on the floor and stare up at the lights when she needs a break. The suspense of this book—and it is, in its own understated way, suspenseful—is whether or not she will leave. But I think the clever trick of the book is to ask why I was so invested in Frances quitting. Why did I want something different for her? She’s good at what she does. She’s kinder to her coworkers than most anyone in the office. The job helps pay for her life. Who was I to tell her that she should do something else?

“The thing that we are kind of brought up to expect from stories is the individual overcoming what’s around them,” says Lin. “And in Young Frances I guess the expectation is at the end, she would realize she’s better than it all. And she would go to do the better thing and kind of indulge in whatever fantasy life she had . . . I wanted to poke at this expectation and I wanted people to be a bit disappointed in the outcome because it’s almost too realistic. It’s too much like life.”

It isn’t clear what state of economic need Frances is in, beyond the fact that she’s prudent with her finances, in stark contrast to Vickie. Vickie borrows money from Frances; her rent checks bounce.. The two of them exist in a vacuum—there are no families to speak of, no indication of what their socioeconomic background is. As a result, the tone of Young Frances feels relatively apolitical. The law firm is cutthroat and corporate, and Castonguay is looming and creepy. But Frances isn’t a whistleblower. She’s not trying to stick it to her ridiculous overlords, who can’t remember their employees’ names despite the fact they’ve worked there for years. And yet she wields what little power she has lightly, advocating for her coworkers when she can, all the while maintaining the power structures of the system and eventually making her way into management.

“I’m trying to acknowledge the fact that everyone plays a part,” says Lin. “We tend to lionize certain types of people. And some of those people are honestly like the scariest people that you don’t want to spend any time with. And some of the people that you would never valorize are going to be the Frances of the world, who do have a lot of moral complexity and a huge amount of thoughtfulness inside.”

There is an irony to all of this, which is of course that Lin took the opposite road as Frances. He turned down the stable career path to pursue being a full time artist. His work is aligned with his passions, what he’s interested in. He’s had success—his debut graphic novel was nominated for a prestigious Eisner award, and you can find his cartoons in The New Yorker. But as any freelancer knows, this path is rocky, full of uncertainty. Drawing comics is painstakingly slow and laborious work. He doesn’t necessarily feel like he made a better decision than Frances.

“Well, no one should listen to me, I’m the total hypocrite,” laughs Lin. “I’ve escaped the ranks of being a bureaucrat. And I totally indulge my weirdest inclinations.” He adds: “I thought it was really important for me to not pat myself on the back for being an artist through the character of Frances… Honestly, I feel I took just the lazy hedonistic approach to life, and that’s just my personal thing.” In the beginning, he was reluctant to tell people in his office that he was a cartoonist, and relished the anonymity a pen name granted him. He didn’t want them to feel like he wasn’t taking the job seriously, or thought he had something better to do.

Lin’s parents came to Canada as students from Taiwan in the late sixties. Being the child of immigrants shaped the way he thought about his future. “For so many years, my thing was just about being practical. Like I studied psychology in school cause it was the only thing I could think of that was remotely about helping people. I specifically didn’t want to study English lit even though I was interested because it just felt too indulgent. And I didn’t go to art school when in high school people were telling me to go to art school just because again, it just felt way too indulgent.” Lin said no matter what did though, he could not stop writing stories and wanting to express himself.

By the end of my conversation with Lin, I still didn’t know how to square his personal journey with art with Frances’ story. It’s linked to one of the many contradictions central to Young Frances—a job doesn’t define a person, and yet it must surely shape the way they see the world. “When I meet someone I want to know about their jobs,” says Lin. “And it’s kind of like commonly known as the dullest question you can ask someone. But at the same time, I’m like, how could that not matter. If someone spends like eight hours every single day, even if it’s something they don’t care about, it’s going to affect how they see the world and their value system.” Of course it makes sense that people would want to find meaning in the thing they do for the vast majority of their time—but as the writer Clio Chang described in her piece for The New Republic, the concept of a “dream job” can also be a means of exploitation, demanding from someone an unhealthy level of fidelity to their work.

In 2018, when the graphic novel came out, Lin worried that the kind of office workplace desperation he was depicting would no longer resonate—it was a time of greater economic stability (for some). The first time the two of us spoke, it was in the middle of an ongoing pandemic and a new recession was upon us. In the months that passed between then and now, and when I wrote the first draft of this essay, something else was happening: millions of people were quitting. The news articles were calling these record-breaking numbers “The Great Resignation.” For many workers, the pandemic forced them to confront the fact that the conditions of their working life were untenable: underpaid, underappreciated, and overutilized.

So I reached out to Lin to ask him if he thought the book would resonate differently with readers now, in this particular moment, when so many of us are reconsidering what is reasonable in a job, and what isn’t. Young Frances was born out of a particular economic moment—and now contemporary readers find themselves navigating another. “I think the high pressure work conditions aspect of the story might resonate a little stronger now,” Lin wrote. “But for better or worse, I don’t think that subject will ever become super quaint or outdated. As long as there’s capitalism and this competitive, anxious drive for businesses to stay on top, we’ll get work environments with insane expectations. If you aren’t currently experiencing those pressures, you probably know someone who is.

He added: “I was interested in how a young person encounters and sort of acclimates to a heightened work environment. It’s productive, but there’s an emotional toll… I think one of the most human things is to contemplate quitting your job and to feel incredibly guilty about it.”

Smarter people than me have theorized how this period of history will reshape the way we work, if we will return to offices at all, if we will recreate a system in which workers of all types are taken care of better, if we will organize to get what basic essential human rights we require. Young Frances doesn’t tackle that political stance, doesn’t attempt to reinvision the world as it could be. But it does challenge the notion that work is supposed to be a hyper individualized pursuit, destined to give us meaning. Frances asks a more immediate and present question to herself: how is she supposed to decide what she wants to do with her working life?

Plagued by this question, she goes on a lark to visit a spiritual advisor Vickie recommends. It’s cold outside, the days are getting shorter. The spiritual advisor is flummoxed by Frances. So she levels with her—she says: “Here’s a problem—winter’s here now, but it always seems longer than it should be. Why is that? It’s because we’re built with the physical needs of animals, but the imaginations of gods. We call that a paradox. So what’s to be done about the long winter?” Is this a metaphor? asks Frances. No, she’s informed. It’s reality.