In May of this year, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat tried to solve the Incel crisis. Incel means “Involuntary Celibate,” and describes a community of men who, by their own admission, can’t get laid. Every couple months, it seems, an Incel makes the news by shooting up a school or running over people in a van. Along with Nazis, they’re our most important terrorists these days. Incels see their plight as a political issue; the atrocities they commit are a protest against a world that has excluded them, they claim. If the world was functioning properly, they say, they would all be hot commodities on Tinder. Said Douthat, “If we are concerned with the just distribution of property and money, why do we assume that the desire for some sort of sexual redistribution is inherently ridiculous… the sexual revolution created new winners and losers, new hierarchies to replace the old ones, privileging the rich and socially adept in new ways and relegating others to new forms of loneliness and frustration.” If women are just merchandise, says Douthat, why not let the government re-distribute them, like a subsidy for sociopaths? This solution looks at women, not as thinking, feeling, beings, but as baubles, as accoutrements; constituent parts of the American Dream. At no point does Douthat suggest de-commoditizing our relationship with women, since, in neoliberal capitalism, everything is a commodity.

A coping strategy employed by lonely Incels is to adopt a Waifu, or imaginary wife, who is in fact a character from anime. “Waifu” is itself a Japanese-English appellation of “wife,” and this cringey combination of Asian languages and English is called “Engrish.” The imaginary anime boyfriend is the “Husbando.” Asia has long served as a nexus for the fantasies of western men—we all know the “Asian fetish”—and many anime fans are what is known as, half-pejoratively, “Weeaboos:” westerners obsessed with Japanese culture, especially Anime and Hentai, Anime’s pornier manifestation. In Weeaboo culture, a preference for two-dimensional women has an acronym called 3DPD, which means “Three-Dimensional Pig Disgusting.” Many Weeaboos prefer the weightless flatness of cartoons to the body of a woman. As myanimelist.net exclaims, You May Now Kiss Your Screen!

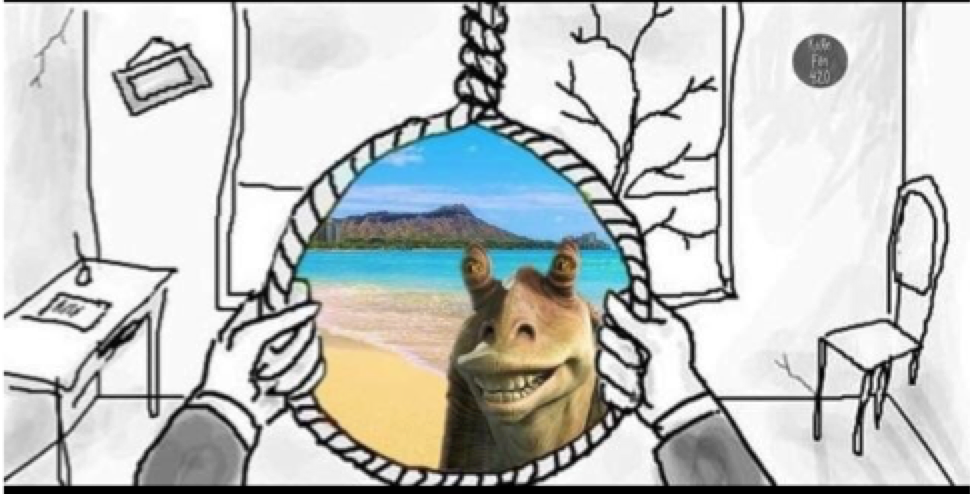

A series of memes called Portal to the Anime World illustrates the plight of Waifu-having, Weeaboo Incel-types. In Portal to the Anime World, an anime girl is gesturing at the viewer from the space within a noose, beckoning us to hang ourselves and join her. This union is almost certainly impossible, since, whatever happens after death, anime is probably not included. Which means the meme is calling for a union that it knows it cannot have, it’s a lament for a desire that can never be achieved. The meme concedes that loving animations is unbearably one-sided. Thus does the withdrawal into the digital constitute a kind of death-rehearsal, like one pre-emptively lying down inside a coffin and getting a head start on forever.

A series of memes called Portal to the Anime World illustrates the plight of Waifu-having, Weeaboo Incel-types. In Portal to the Anime World, an anime girl is gesturing at the viewer from the space within a noose, beckoning us to hang ourselves and join her. This union is almost certainly impossible, since, whatever happens after death, anime is probably not included. Which means the meme is calling for a union that it knows it cannot have, it’s a lament for a desire that can never be achieved. The meme concedes that loving animations is unbearably one-sided. Thus does the withdrawal into the digital constitute a kind of death-rehearsal, like one pre-emptively lying down inside a coffin and getting a head start on forever.

The meme reminds me of a poem by John Ashbery called “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” which describes a Mannerist painting by Parmigianino of the same name. In the poem, Ashbery acknowledges how seductive the painting is, but laments how little it ultimately gives him. Over and over, he describes the painting’s broken promise. “…the soul is a captive,/ treated humanely,/ kept in suspension, unable to advance much farther/ than your look as it intercepts the picture.” The act of looking at the painting, of attempting to connect with it, just leaves one feeling emptier, and, as the poem says, “unable to advance.” Doubt is cast upon the premise of connection and its rituals: the expression of the face in the painting is a, “…pure/ Affirmation that doesn’t affirm anything.” We recognize the guaranteed fulfillment the internet offers, the promises of gratified serenity as our desires turn into algorithms. But the lure of connection only gives way to an image, and images are only ever surface. Connection is depth.

The meme and Ashbery’s poem describe a similar kind of failure to connect. But the moment of the Ashbery poem—1973—is different than our own, which makes Portal to the Anime World more frightening. 1973 was a formative year of Postmodernism, a complex cultural movement which is difficult to explain, even almost fifty years later. Postmodernism said that the foundations of Western thought—rationalism and reason and objectivity—were little more than wishes. No idea or object had a stable identity, just a random place in history’s unreliable narrative, like a life preserver floating on the ocean. Says Ashbery in the poem: “Each person/ Has one big theory to explain the universe/ But it doesn’t tell the whole story/ and in the end it is what is outside him/ That matters…” Everyone has theories; no one’s right. We can’t be right; there are no master narratives anymore. Many people rightly heralded the possible end of Western hegemony, but Postmodernism left a void behind, and no new collectivity emerged. The pumped-up version of capitalism we now call neoliberalism stepped into this empty space, like a kind of evil stepdad. The economist David Harvey defines neoliberalism as “…a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets and free trade.” He goes on to say that neoliberalism, “…has become incorporated into the common-sense way that many of us interpret, live in, and understand the world.” This vision, which defines conservatism now, “seamlessly occupies the horizon of the thinkable,” as Mark Fisher puts it. An example of this in practice might be the raw Darwinian marketplace of Tinder, where no one ever swipes right on an Incel. But how else is one supposed to date? Should our hypothetical Incel take a Tango class? No one wants to dance with Incels, either. In capitalism, there are only winners and losers, and Incels are the losers in the marketplace of sex.

To Ashbery, Postmodernism was a dream, and we might someday awaken, but the meme says only suicide can free us. The anime fan depicted in Portal can’t break the cycle, so he suffers from what Mark Fisher calls “Depressive Anhedonia,” the inability to seek anything but pleasure. The point-of-view in Ashbery is languid, cryptic, wistful—as with all of Ashbery—while Portal is whimsical, yes, but also vicious. And like all lasting memes, it’s a nimble template for expressing a desire for the impossible. It is used in elegies for a vanished natural world (fig b) or any cultural obsession—however ironic or sincere—that cannot really be inhabited (fig c). There’s a sense of dread and loss that hovers in the poem, but it’s nothing like the violence of the meme, whose subject has given up on girls. In the meme, discarding women means rejecting the complexity of lived experience. The meme depicts a willful suicide-by consumption that’s bleaker than the Ashbery by a very wide margin. In Portal, the subject would rather be in love with death than with a person.

This brings up another major difference. In the Ashbery, the self is puzzled, but only by an image in a mirror, or a painting of an image in a mirror; in other words, by the mystery of himself. This is serious, but it’s august as a philosophical issue. But Portal reflects a new terrain in the cultural unconscious, in which the self is estranged, not from itself, but from otherness, in ways that have to do with gender. This century has seen dramatic changes in the ways that people live their genders. Most of the attention has been focused on the LGBTQ community, but not as much is said about CISgender heterosexual men, especially those on the conservative side. If Incel communities and 4Chan are anything to go by—and, considering their prescience over everything conservative these days, I say they are—what we’re seeing is a kind of withdrawal from heterosexuality, as though the “other” is no longer worth the trouble. The otherness of women, in their eyes, has become a kind of terra incognita, a place they will not go. In patriarchy, the mystery of women is a very old idea, but technology has made the dream of total separation almost possible. The contempt for women in certain online realms is something to behold. “One day incels will realize their true strength and numbers (sic) and will overthrow this oppressive female system,” wrote Eliot Rodger, the UCSB killer who took the lives of seven people, four with guns and three by stabbing. “Start envisioning a world where women fear you,” he continues. These comments were made on a message board that used to be called PUAHate, or “Pickupartist Hate,” and is now called “SlutHate.” To these communities, Feminism has utterly perverted female life. Said the Men’s Rights Activist Paul Elam, “Male-bashing feminists, contemptuous of the patriarchy and the traditional role of women in it, are alive and well and more politically powerful than ever.” Women are promiscuous and mercenary now, we are warned, and the idea of “Rape Culture” is a hoax, and a vehicle for disempowering men. Said conservative columnist George Will in the Washington Post, being raped is “…a coveted status that confers privileges.” The divide between men and women is explicit now, and baked into conservatism, which sees feminism as the enemy, end of story.

It’s impossible to explain how we arrived here without the catalyst of the internet, which legitimized this kind of crazy separatism the way it does with any bad idea that has enough adherents to form a group. “The technologies we use have turned into compulsions, if not full-fledged addictions,” writes Nir Eyal, in his book Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, and what a title that is, by the way. “It’s the impulse to check a message notification. It’s the pull to visit YouTube, Facebook, or Twitter for just a few minutes, only to find yourself still tapping and scrolling an hour later.” This predicament, says Eyal, is “…just as their designers intended…” And yes, from the perspective of the siphoning of our dreams, and their endless monetization, the internet is ferrying us from place to place with almost no resistance. One thing one might not do, as an addict, is critically explore the nature of addiction, or the ways in which particular desires—say, for women—might misunderstand the truth of actual women. Ensconced within a world of digital promise, one might invent a separate sexual cosmology with no correlative in real life. The internet tells everyone their fantasizes are true, as a way to keep them online, keep them shopping, keep them generating clicks and metadata. Nothing is inducing us to come back to real life, and even if we wanted to, addiction might not let us.

An anime girl is not just an animated girl, it’s a symbol of withdrawal from actual women. But the fact that Portal to the Anime World exists, and is re-made over and over, shows these anime addicts know, to some extent, what they are up against. They know they worship loss, that they have made their emptiness an idol. Portal to the Anime World is a knowing self-critique at the end of the world, a message to the aliens who will land on Earth when all the human beings are dead. The message says, We couldn’t stop, LOL.