Decades later, Ben Ratliff, former pop music critic at The New York Times, can recall the details of a song he heard once, but that it is impossible for you to listen to. I’m sorry to report that it cannot be streamed. It cannot be purchased on a compact disc or a cassette, used or new. There’s no rare vinyl pressing listed on Discogs. Ratliff’s bit of recollected music criticism, shared over email, is a kind of ghost story.

My friend Laura Cantrell and I were in Nashville, her hometown. She talked our way into a Johnny Paycheck recording session, during a period after he’d shot someone and was appealing the charges. I think he was commercially dead because of the shooting incident. I was in awe of this homunculus, whose records I deeply loved, a terrible and charming person. On that day he seemed animated but tired—he’d clearly stayed up all the previous night. What were we doing there, college kids, unconnected nobodies? It was cool. I was sober as a judge but basically eye-pinned during this experience. These were the circumstances. I don’t know what the recording session was for, but when he got out of the booth he entertained the engineers and the producers and us with a whole stream of songs that I remember as harrowing. One was called “Looking Through the Eyes of a Dead Man.” It was bright and up-tempo, like skiffle-tempo. Insane. A jaunty and almost jubilant song about death-in-life. That day he told me that it was to be part of an autobiographical record he was working on called “The Album of a Life.” As far as I know he did not get to finish it. I asked him some years later if that song did indeed exist, at least in his head, if not on tape or on record, and he said it did. I can’t find it online. He’s long gone now.

When you work in the music industry, you often get to hear a piece of recorded music before it is filtered through the machine of a record label. At that time, before a marketing campaign has been deployed, the work is still subject to change. Sometimes you encounter a song that will not fade away, though you never hear it again. “Looking Through the Eyes of a Dead Man” may indeed live on magnetic tape in a box of studio detritus in a closet somewhere, but without Ratliff’s story, there is nothing else to go by.

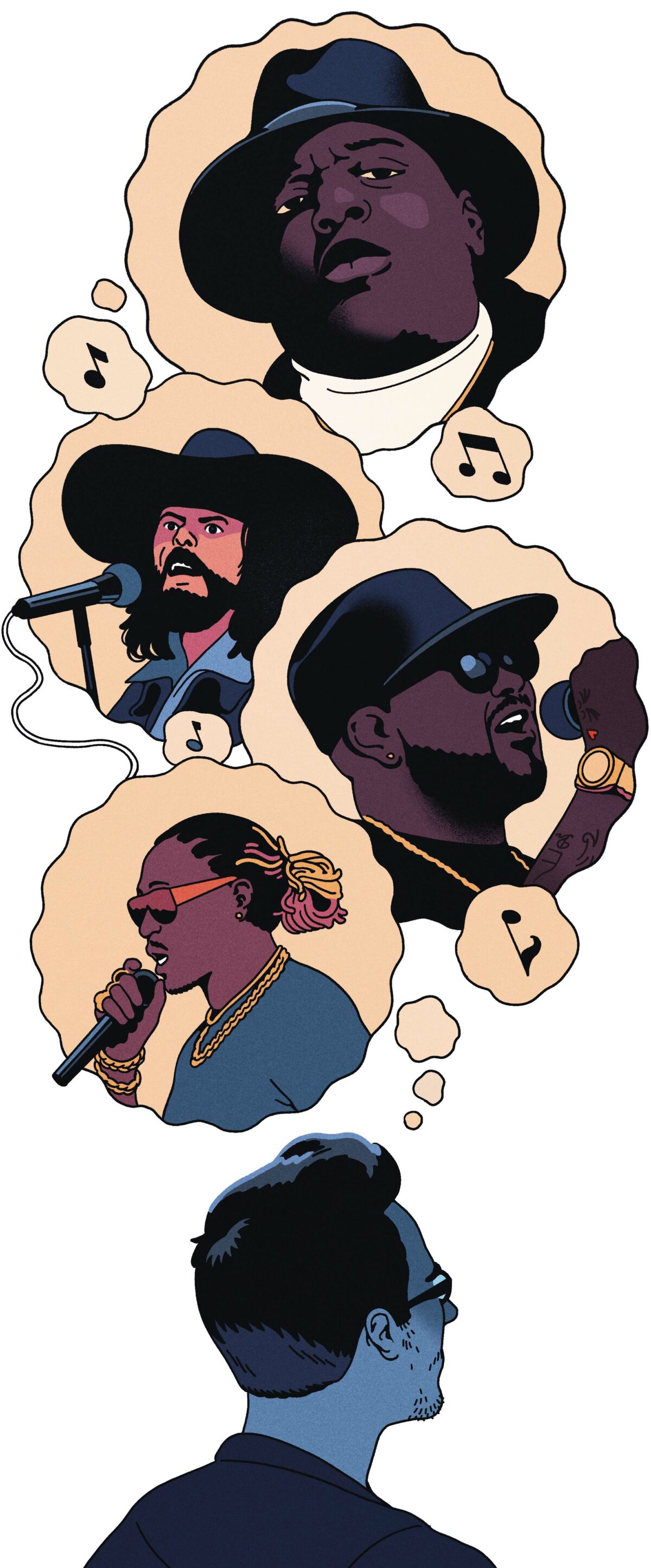

Speak with enough music journalists and these stories bubble up. Like the time Biggie didn’t know how to get to the studio.

It’s 1992, or thereabouts, and Christopher Wallace, newly signed to the polished R&B label Uptown Records by Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, is booked for his first real studio session for his debut album. He’s a young man most accustomed to his neighborhood, Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill, and truth be told he’s super nervous about this appointment at Platinum Island, in downtown Manhattan. So he asks his friend and neighbor, an NYU film student and journalist named dream hampton, for directions. As Biggie is poised to make his mark on the world with his hyper-detailed storytelling and verbal style, hampton is on her way to becoming one of the greatest journalists to document hip-hop, writing with candor and care about Snoop Dogg, Tupac Shakur, and her friend Chris—soon to be world famous as the Notorious B.I.G.

She tells him: “Yo, you just take the C at Clinton–Washington, transfer at Jay Street to the F, take that to Broadway and whatchamacallit.” Follow these instructions and then hoof it up the subway steps to eventually arrive at Platinum Island, at East Fourth and Broadway—easy. He tells her: “Nah, you coming with us.” So hampton does, and hangs around while he works. Puffy has wisely put a more seasoned force in the studio with Big: Ol’ Dirty Bastard, the Wu-Tang Clan’s most irrepressible member, though at the time he goes by Ason.

Surrounded by the “attendant things” of the studio—the greenroom, the drinks and the weed, the “dorky white boy tech guy”—the duo records a song. “Ason was doing his pre-Drake singing bullshit and it was just great,” hampton recollects over the phone. “He made Big feel so comfortable.” What they put to tape is ferocious and raw, and ultimately doesn’t make it onto Ready to Die, the Notorious B.I.G.’s landmark saga of the everyday struggle in Rudy Giuliani’s New York; doesn’t become a bonus track on the anniversary edition; never finds its way onto any posthumous release. hampton doesn’t know if it was ever mastered. While she talks, the song comes briefly alive. It is about as rare and special a song as can be, recorded by two legends dead long before they could be old.

There are a few ways to catch the song. Ratliff and hampton had their encounters off the clock, so to speak. In the industry there are on-assignment studio sessions where the writer shadows a musician for a story and gets a glimpse of something in progress that never leaves the windowless, soundproofed room of its creation. Insanul Ahmed, a writer who worked for Complex and Genius, can still hear a beat that Earl Sweatshirt played in 2012 at Mac Miller’s home in Los Angeles, when Ahmed was profiling Miller. The late rapper had converted a small pool house into a recording studio that on any given night welcomed many of the region’s most talented artists. Ahmed felt uneasy about this particular arrival because Earl had recently dissed Complex on a new single, “Chum.” (He called out the staff, of which I was a member at that time, as “fuck n—.”) “I don’t know if he knows who I am,” Ahmed thought—and he didn’t exactly want him to find out. (Hostility toward the press is something of a tradition in music journalism, and Ahmed is no stranger to it, as evidenced by a well-publicized phone confrontation between him and the rapper Wale.)

Earl sat down at the console and took over the room, playing music from what would become his debut album, Doris. Then he played beats of his own that he wanted to send to other artists. “I want to give this to André 3000,” he said, queuing up a fresh selection. “It sounded like early morning in the jungle,” Ahmed says. “Like, the sound of orangutans was part of the beat. It was crazy, with a really long build a full minute before it opened up. It was an art piece. I can still hear it in my head.”

Some beats have a clearly defined pocket for an emcee to rhyme within, but this was inscrutable. “I don’t know how someone would have rapped on it,” Ahmed says, “though I guess André would have figured it out.” There’s little reason to doubt that he would have, André being André, but there’s no record of it happening.

Outside the studio there are advance copies. In the heyday of print, before rampant piracy and file-sharing on Napster, a cassette or CD would be shipped by the label to members of the press for coverage consideration. Mailed many months out from the release date in order to meet print deadlines, an early iteration of an album sometimes contained songs that wouldn’t make the final cut, the result of further tinkering, or, in the case of many a hip-hop project, a sample-clearance issue. Nowadays, high-profile rap albums only rarely get shared in advance. If something unfinished circulates widely online, it’s likely the result of someone hacking an artist’s email.

Then there are listening sessions, where a label executive or publicist will summon a cadre of journalists to a nondescript carpeted conference room in Midtown Manhattan, where many labels and magazines have offices, or a cramped studio, to play the album closer to its release. Sometimes, the artist will travel to the publication’s offices to play forthcoming music, and even though this occurs with regularity, it always—always—results in a screwball comedy of errors to get the speakers working. I shudder as I write this, reliving the interminable afternoon when the R&B singer Omarion and an entourage of a dozen watched mournfully as my colleagues and I flailed in our attempts to unlock the secrets of Bluetooth technology in real time.

Conversely, Naomi Zeichner, a writer and tech worker who served as editor in chief of The FADER, remembers the camaraderie these collisions between the press and an artist could inspire. Handlers and artists would stop by to present half-finished albums, looking for feedback on individual songs or the eventual sum of their parts. “They were there to play music, but also to pitch the narrative they hoped we’d be developing together as part of a long-lead magazine story,” she says. “It was an opportunity to sniff each other out and build trust, or spot red flags.”

In 2013, her favorite artist at the time, the Atlanta rapper and heart-on-his-sleeve balladeer Future, played an in-progress version of his sophomore album Honest for the magazine’s staff. One track, a gem of brooding horniness called “Good Morning,” imprinted on her in such a way that when a version of the song, with a similar melody and different lyrics, appeared months later as the Beyoncé single “Drunk in Love,” she felt as heartsick as she did proud. Both songs were produced by Detail and seemingly written around the same time, with the bigger star unsurprisingly winning rights to its release. (Future does not have a writing credit on Beyoncé’s song.) “‘Drunk in Love’ is an incredible song,” she says, “but it felt tragic that Future never released his version, which I thought proved his talent beautifully and which I had been waiting to hear again for months.” “Good Morning” was never commercially released, but there are rips and performances of it online. A decade later, Future remains a chart topper, but the real heads will always wonder about the path not taken.

“There are tons of instances where I heard a song on the advance that didn’t make it to the retail version,” Joseph Patel explains over the phone. An Oscar and Grammy winner for coproducing the 2021 film Summer of Soul, Patel began his career writing about hip-hop and R&B for Rap Pages, Paper, and Vibe in the late ’90s. That’s how he heard the ur-version of Kanye West’s “All Falls Down,” with the Lauryn Hill sample, rather than the smoother Syleena Johnson interpolation; the first Clipse record, Exclusive Audio Footage, which included one Neptunes production that went to Jadakiss after the album was shelved by Elektra Records; and a very early draft of the N.E.R.D. debut, In Search Of…, which included two songs—“Why Must I Die” and “Here She Comes”—that never emerged anywhere else.

On YouTube, the site that I’ve come to think of as the most important music library on the internet, I found “Guilty Girl,” an excellent Puffy-produced Kelis song intended for her 2003 album, Tasty. Patel told me about it—the self-lacerating midtempo cut about wanting to cheat had stayed with him for almost twenty years, in part because he’s from the Bay Area and the song used the same sample as “93 ’til Infinity,” the quintessential Northern California backpack rap track from Souls of Mischief. As of this writing, it’s still available on YouTube, with fewer than five thousand views in the almost twelve years since it was posted. It sounds like a single to me, but at some point someone with power disagreed. “I’m about to make you hate me,” Kelis sings on the hook, her sandpaper voice as pained as it is honest.

On YouTube, an upload like this is considered “user-generated content.” Like a dubbed cassette, it’s a pirated release that doesn’t track back to a rights holder of the song; that is, it’s not delivered to or claimed on the platform by a music rights holder—even though the song was technically funded with the coffers of no less a powerhouse than Sony Music, and the “users” behind the song’s creation included Puff Daddy and the artist who sang the hook on “Got Your Money.” There’s no telling how it moved from the studio to the anonymous account that uploaded it.

YouTube even hosts a portion of the song that the Notorious B.I.G. and Ol’ Dirty Bastard recorded that day at Platinum Island (with dream hampton in attendance), though it’s incomplete, cutting off the second verse from Biggie after a handful of bars. It is an abridged document of a momentous day in music history, and it’s also something of a false start. The verses you can hear on this upload appear in their complete form on two solo songs from Big and ODB: “Gimme the Loot” and “Brooklyn Zoo,” respectively. Those finished songs sound better than what you hear on the leaked excerpt.

I would love the opportunity to test my memory of my lost song, my grail, to know if it’s as good as I remember. In early 2015 I went to a Manhattan listening party for a forthcoming release from The-Dream, one of the architects of contemporary R&B and a personal favorite. I went with my friend and colleague Damien Scott, also a devotee. With catering from Miss Lily’s and a trim guest list, this wasn’t representative: typically you’re shoulder to shoulder in the studio sipping tepid Cîroc from a plastic cup; the volume for the looped advance single is deafening; and when the album playback begins, there’s only the performance of listening amid rampant picture snapping and networking.

This night was different. After the requisite milling around and greeting the writers, podcast hosts, and publicists, The-Dream introduced Crown, a concise return to form after the lackluster IV Play, the first shaky release in a career that was otherwise stunning for its ingenuity and ambition.

When the project finished playing, Damien asked if they would run back a song called “Cedes Benz.” I didn’t know you could make a request like that. I was years into my career and I still hadn’t tested enough of the limits. Rooms like that could bring out a capacity for ingratiation in myself that I didn’t like. Outside the office, at the label or at a show or in the studio, I wanted to sink into the furniture or blend into the walls rather than stand out. When Damien asked, it was obvious how well the move worked as flattery—his request excited The-Dream. But he hadn’t meant it as a move. He really wanted to hear it one more time. This is why I’ve heard twice the best song I’ll never hear again.

There’s currently a version of “Cedes Benz” available to stream, but it isn’t what I heard The-Dream play that night in 2015. For over three minutes, I listened, stunned, as he broke into a pulverizing near-rap cadence about the splendor of German engineering and the power of driving a car so clean it makes your rivals sick. The production skitters and grinds, replicating the commotion and noise of combustion underneath the hood. Then he brings in his girl, who looks so good it renders irrelevant the car he’s hyped up. She’s so bad that “these bitches hate it when they see her. / Bet you thought you was a diva, and she should apologize: Baker, Anita.” The beat falls out and something sleek glides in, built from the velvet bones of Anita Baker’s 1994 hit single “I Apologize.” The-Dream duets with Baker as she sings with heartrending contrition. At once airy and deep, her voice is a feather capable of knocking you backward. And the way her strong alto pairs with The-Dream’s boyish upper range is nothing less than fantastical. The unexpected joy of these voices brought together created an illusion so beautiful I wanted to live in it.

That’s how I remember it, anyway. We ate banana pudding afterward.

Listening to the song now is a tease: the door in time created by the mention of Baker’s name never opens for her to step through. She’s summoned, but the sample doesn’t arrive. She wouldn’t clear the rights to use it; he recorded a new piece of music that feels indebted to her without using any of her music. It’s merely good instead of miraculous.

I tried to hear the song again but had no luck. Even The-Dream’s engineer turned me down, saying the song wasn’t his to share. I get it. When I explained my predicament to Ratliff, he gave me the linguistic equivalent of a smack upside the head: “You’re asking about recorded music, but I can’t help thinking that’s a very small part of what a ‘song’ is,” he wrote. The power of the impermanent music experience is “more than a matter of recordable and copyrightable sound. I love being told, ‘Sorry, fucker, you will never hear this again.’ Let the great thing have its ungovernable value.”