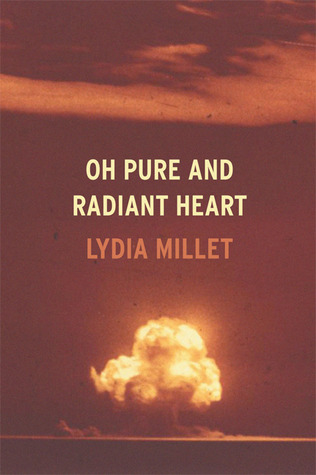

Lydia Millet’s Oh Pure and Radiant Heart, a sprawling novel founded on an ambitious and unusual conceit, begins when a woman in present-day New Mexico dreams of Robert Oppenheimer and a mushroom cloud. Soon thereafter, she encounters Oppenheimer while running errands around town.

Other than her apparent ability to conjure controversial historical figures from the beyond, Anne is an American Everywoman: she has a good job as a suburban librarian, a cute house, and a sexy husband who adores her and is eager to start a family; her grass seems fairly green. But instead of stagnating in her small town contentment, Anne persists in viewing the world as a threatening dystopia and can’t help but search around for something more largely meaningful to fill her days. Enter Oppenheimer, inventor of the atom bomb, and his lab cronies, Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi. Lacking enough faith in the future—or the present, for that matter—to bring a baby into the world, Anne trails this unsuspecting trio from the past. She eventually invites them home, where they are accepted by her accommodating if mystified husband.

The magnetic Oppenheimer, the fat and cheerful Szilard, and Fermi the depressive tagalong are understandably confused to find themselves alive in the twenty-first century wearing sixty-year-old suits, and become subsequently dependent upon this fawning woman for cultural tour guidance. Aside from Szilard, who learns rap lyrics and becomes fascinated by the internet, the scientists share Anne’s alarm at the progress-as-decline that has transpired since their deaths, and they begin to wonder if the poverty of modern culture is somehow their fault, traceable back to their destructive invention. Meanwhile, shady military agents start to track the scientists. Anne quits her job and spends her paltry savings to fly them to Japan, where they hatch a plan for a world tour designed to promote peace. The main attraction of the tour is Oppenheimer, a figure who inspires nostalgia for a past era with his bright, clear eyes, lanky build, porkpie hat, discerning tastes, and ever-present cigarette. Millet shines in her ability to portray her characters and all their quirks, relying on self-consciously exploited tics—all fools in the book sprinkle his or her speech liberally with “like,” for instance. Szilard is a selfish and lusty eater who caps every scene shoving a pastry into his mouth. Oppenheimer accessorizes with his perpetual cigarette.

Given the book’s scope and aspirations, it’s no surprise that it entertains multiple genre identities: it’s part feature film, part political commentary, part comedy, part cautionary tale, and part interior monologue, with several of the primary characters continually churning in deep thought. Millet’s philosophical examinations and historical notations are threaded between a series of lighter scenes, but her attempt to offset the heftiness of nuclear warfare with personal epiphany can, at times, feel like a futile endeavor to shrink the magnitude of destruction, past and future, down to a manageable size. For readers wanting a straight-up factual read to commemorate this year’s sixtieth anniversary of the first atomic attacks, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman, a recent biography of Robert Oppenheimer, will likely be the ticket. But for those seeking a character-driven slapstick conjecture about the history of atomic warfare and its consequences, Oh Pure and Radiant Heart provides catharsis and education while allowing us to bask in the humorous, poignant possibilities of what if.