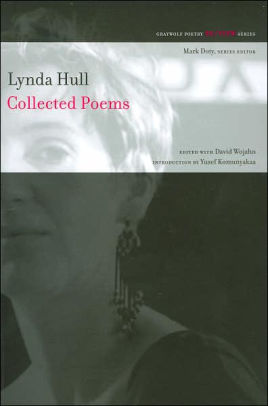

At the time of her tragic death, at age thirty-nine, in a 1994 car accident, Lynda Hull had published two prize-winning poetry collections and she’d written the poems that would become her posthumous third book. Her lush, intensely lyrical evocations of the underbelly of American urban life, driven by a sense of inevitable loss and degradation but also by a powerful attachment to momentary beauty, made her poems required reading for many in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Long out of print, Hull has slipped out of the consciousness of a younger generation of readers. Now, all three of her books are available in a single volume. It has much to teach us, especially at a time when irony and fantasy are the poetic flavors of choice.

From the start, Hull, like Elizabeth Bishop, was a poet of description. Much of the action in her poems takes place in the unfolding of detail. Like Hart Crane, Hull’s favorite poet, she is a writer for whom the cityscape is rife with metaphors, evident in both writers’ densely packed lines. Ghost Money (1986) begins at the moment “when the last commuter trains etch / black signatures of departure over tracks.” These poems are mostly preoccupied with other people—often her parents, whose childhoods she re-creates, already using her shapely stanzas and sweeping cinematic lens. She records a grim vision of a place where “there are no innocents,” where “the men all look / as if they’d never had mothers,” and “something of love was cruel, was distant.” Later, she would focus that lens on herself.

Star Ledger (1991), Hull’s best and most cohesive book, returns to the Newark, New Jersey, of her childhood, a place that people “leave / for lives of poverty, crippled dreams,” then launches into harrowing poems about one such life: hers. After running away from home at seventeen, Hull married a man from Shanghai, spending much of her youth in Chinatowns in several cities, including New York, where she often sets poems about drug addiction. Her unhappy marriage was one in which “he’d / touch her shoulders, her neck, but each touch / discovered only the borders of her solitude.” Those borders occur where the self meets the other, and these almost compulsively descriptive poems attempt to bridge that seemingly uncrossable gap. Redemption comes, if at all, in the form of painful clarity, in “a way of finding beauty at the point / it is altered.”

In her last book, The Only World (1995), Hull looked back over a troubled past from a place of relative calm, and wrote movingly about narrow escapes from “Parallel lives, the ones / I didn’t choose.”While it’s more scattered than the previous two books—the poet David Wojahn, Hull’s second husband, compiled it after her death—it contains her best individual poems, exemplified in the extraordinary long poem “Suite for Emily,” which evokes the life of a close friend and drug buddy who ends up in prison with AIDS. Interweaving biographical details with snippets from Emily Dickinson, “Suite for Emily” takes a trip through hell, culminating in a gutsy confrontation with Death itself: “Death you have taken my friends & dwell / with my friends. You are the human wage. / Death I am tired of you.”

There may be something cold, too deliberate even, about Hull’s work, as if she were determined to wring certain images and feelings out of her words, rather than allow for discoveries. But Hull’s is a visionary poetry of survival, born of necessity. It offers a tough but powerful consolation: it makes beauty of mistakes.