“The imagination works with eyes open. It alters and is altered by what is seen. The problem is that if we admit this, then the relation between ideas and things turns mutable and inconstant. Such destabilization is bound to affect our understanding of architectural drawing, which occupies the most uncertain, negotiable position of all, along the main thoroughfare between ideas and things. For this same reason, drawing may be proposed as the principal locus of conjecture in architecture.”

—Robin Evans

We live in the age of the chimera—a world of relentless mixing in which anything and everything is a potential ready-made object available for copying, sampling, and versioning. Since the turn of this century, mashup has become part of our popular vocabulary; (we think) the term originated when DJs began using digital tools to make new tracks out of existing ones from disparate sources. Danger Mouse’s Grey Album of 2004, for example, combined the Beatles’ White Album with Jay-Z’s The Black Album. Mashup is the art of stealing and combining incongruous elements in order to construct new alignments and create new forms of legibility. Mashup is stealth collage, meaning that the cuts and seams between fragments are carefully puzzled together to the point of near disappearance. This tricks us into perceiving the work as a synthetic whole rather than a compilation of found parts.

Despite the acceptance of mashup techniques in nearly every other medium, the dominant practices and theories of urbanism are still ruled by the modernist idea that cities should be built like machines: through the rational assembly of standardized parts. This approach too often results in generic solutions for generic cities. But the Fordist regimes of mass production are rapidly dissolving into networks of mass customization. The world has become a space of endless choices, options, and versions, and this applies to architecture and urbanism as much as to everything else. Variability, contingency, and hybridization are the key qualities of the mashup city.

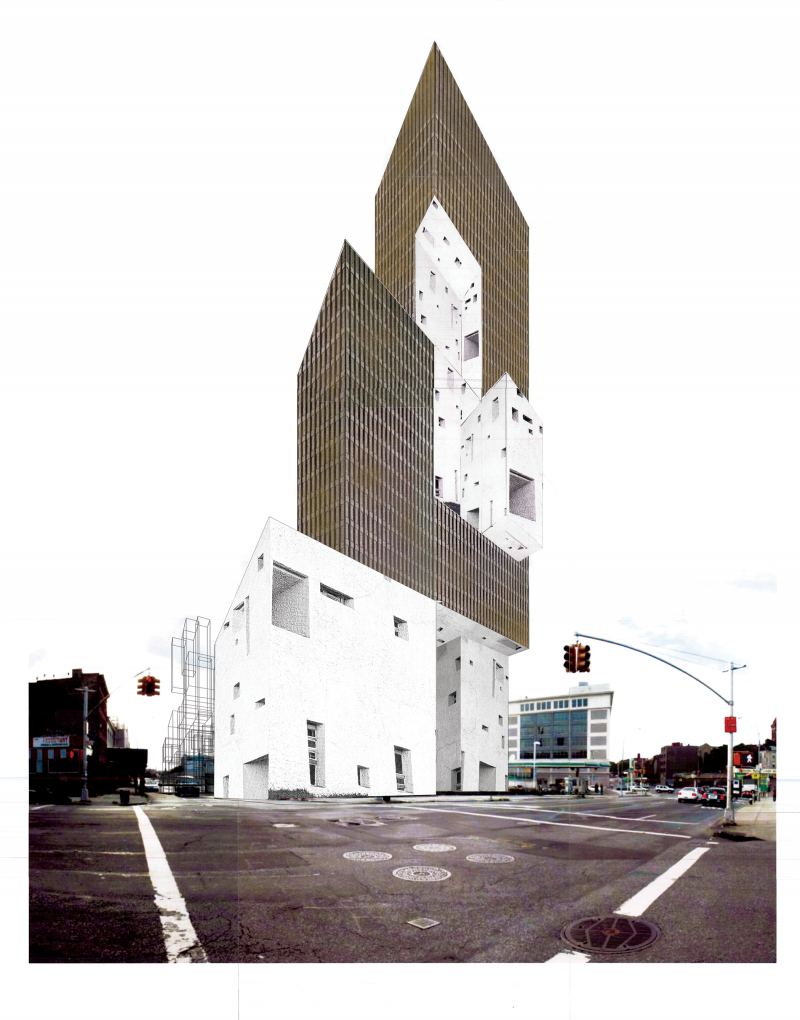

I made these three tableaux (pictured on this page and pages 36 and 96) as part of a project to hijack Frank Gehry’s plan for the Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn, where he was hired by Forest City Ratner Companies in 2003 to design an eight-million-square-foot master plan containing sixteen skyscrapers and a basketball arena. Gehry’s project was announced to great fanfare and with the support of New York’s mayor, Michael Bloomberg; former governor George Pataki; and the Brooklyn borough president, Marty Markowitz.1

Their Atlantic Yards was a classic 1950s-style urban-renewal scheme, but repackaged in the kind of architectural glamour that became standard in New York during the height of the recent real estate boom. Though the project covered seven city blocks and twenty-two acres, Ratner hired a single architect to design one master plan for what was, essentially, a neighborhood. Concerned about the monoculture this arrangement might produce, our team proposed a polyphonic approach that cut the rail yard into eight smaller sites where different developers and architects could compete, communicate, and collaborate with one another and the public. Our design was for a landscape of difference: a heterogeneous space where the incongruous demands of real estate finance, local politics, street culture, and high architecture could be negotiated. The images presented here portray this landscape with manually cut-and-pasted imagery grafted onto a mixture of digital photography and graphics. They explore the idea of mashup urbanism by stealing ready-made architectural fragments from across time and space and reassembling them as visions of someplace else in an alternative future.

As culture becomes increasingly fluid and hybridized, so does the urban landscape, producing situations for which conventional architectural thinking has few tools to either understand or confront. It is often remarked that architects have recently achieved an unprecedented level of influence on the future shape of cities. I doubt that claim is true, but, if it were, that power would not rest in built works but more likely in the pictures that we make in advance of construction. Such images have always had great power to shape the urban imagination. Developers, politicians, citizens, and builders determine realities. We, on the other hand, expand the possibilities, which is in fact a much larger field of operations.