Years later, when he was living in Upstate New York, the sports writer W. C. Heinz recalled his first vision of Red Grange. It was in a dank auditorium at school, where kids paid ten cents to see movies. The projector whirred. There was music. The screen filled with light and there was the Galloping Ghost, a University of Illinois halfback, so named because whenever a player tried to tackle him, he was gone.

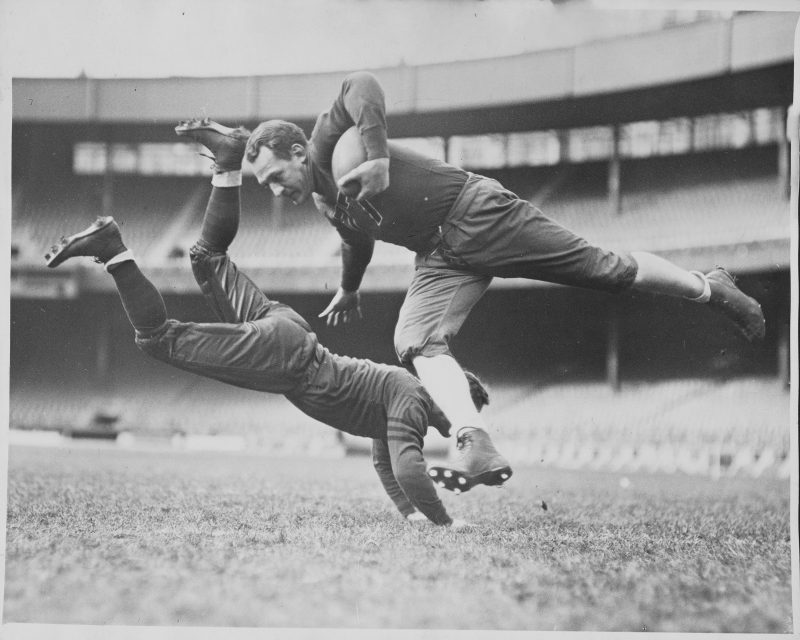

It was one of the first films Heinz had ever seen, so for him it took on the aspect of a dream: Red Grange camps under a kickoff, waiting for the football, then he’s got it and heads upfield. He cuts as he runs—slowing, feinting, speeding up, dodging tackler after tackler. The camera moves close, a leather helmet framing Red’s cheeks and eyes. Even as an adolescent he had a serious, workingman’s face. He cruises by the last defender, lowers his shoulder, and runs at the camera.

The first book I remember really loving was The Red Grange Story: The Autobiography of the Galloping Ghost. It was less the words that captured me than the pictures, black-and-white shots that chronicled each step in his legendary career: Red as a young man in a Chicago suburb; Red at the University of Illinois; Red as a pro in a leather helmet; Red in a snap-brim cap and a floor-length raccoon coat that portended the fur coat of the great Joe Namath. Those images suggested an antique era, the nightlife of another country. How big was he? The morning after Garland Grange caught a touchdown for the Bears, the Chicago Tribune ran the headline: red grange’s brother beats giants on a pass.

Red Grange, America’s first pro football star, was born in western Pennsylvania in 1903, in an Appalachian town where his father was a lumberjack, a brawny man in flannel. When Red was nine, his mother died. The family moved to Wheaton, Illinois. Red’s father became a police officer—the only police officer in Wheaton. The demands of the position meant that Red was without supervision a lot of the time. His afternoons were spent in the street, running among clothesline tenements, getting his first taste. “It wasn’t football we played, but something like it,” he said. “We called it, ‘Run sheep, run.’ There would be two or three guys in the middle of a field, tacklers, and a goal at either end; the goals were sidewalks. All of us would line up on one goal and on the signal run to the other. If you were tackled, you’d have to stay out in the middle and become a tackler.”

Grange persisted, round after round. Even then, he was maddeningly elusive. Most athletes blossom in adolescence, after they’ve grown. A precious few are good when they’re small: Gretzky, DiMaggio, Grange—the aristocrats, the naturals. It’s not about power with them—it’s about vision. They see things others miss: how a play is unfolding, what it will look like in a moment, and the moment after that, and the moment after that.

Grange arrived on the U. of I. campus in Champaign-Urbana in the fall of 1922, carrying, according to Heinz, “a battered secondhand trunk, one suit, a couple of pairs of trousers and a sweater.” He pledged Zeta Psi, and tried out for football. He did not play much freshman year, but word still spread. Even in practice, you could not keep your eyes off of him: the way he moved. Robert Zuppke, a legendary Illinois coach—he coached Hemingway at Oak Park High School—was dazzled. “Red had that indefinable something that the hunted animal has,” the coach explained, “the uncanny timing and the big brown eyes of a royal buck.”

Red came into full power junior year. That’s when he made the runs that remain his legacy. On many afternoons, he rushed over two hundred yards, triple what his closest competitors were doing. And it was not just the yards, nor the points he scored. It was the way he looked doing it. He was the first modern football player, the first great broken-field runner. In the past, the standouts had been power backs like the disgraced Indian Jim Thorpe. They bulled over you. Grange went through or around. No one taught him. It was instinct, what he had learned racing between the brownstones. For a defender, it was maddening. It was the dawn of the Jazz Age, and Grange connected to that spirit. He played out like music, a horn soaring above a dirty scrim

of bullies.

In the summer, he delivered ice, carrying hundred-pound blocks up apartment-house stairs. It built his arms and legs and gave him a nickname: the Wheaton Ice Man. Reporters followed him, snapping pictures of the out-of-season jock grinning because he gets the joke. He was as handsome as a matinee idol. It was said that the women in town put on their best clothes when Red brought the ice.

As his fame grew, so did the crowds. Over sixty thousand fans jammed into the rickety stands. He ran for three hundred and sixty-three yards against the University of Pennsylvania. Against Michigan, he scored every time he touched the ball: a sixty-seven-yard run, a fifty-six-yard run, a forty-four-yard run. Coach Zuppke took him out after just twelve minutes. When he put him back in for one play in the fourth quarter—to quiet the fans—he scored again. By 1924, he was being classed with Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey—a triumvirate—one of the great sportsmen of the era.

When Illinois played at Northwestern, the game was moved to Wrigley Field—then called Cubs Park—because Dyche Stadium, in Evanston, couldn’t handle the crowd. After practicing on the field that morning, many of the Chicago Bears—the NFL was just in its second season—stuck around to watch the kid. He played nineteen minutes, ran for two hundred and forty-seven yards, and scored three times. After an away game, he was met at the train station in Champaign by thousands of students, who carried him two miles on their shoulders to the Zeta Psi house.

When the Illinois team traveled, it was accompanied by reporters, including the great sportswriters of the day: Grantland Rice, Damon Runyon, John O’Hara. It was these men who turned Red from a local celebrity into a national sensation. The nicknames fell like rain: the Will O’ the Wisp, the Titian Typhoon, the Sorrel-Thatched Meteor, the Red Rocket, the Fiery Comet, the Crimson Tornado, the Red Streak, the Fleet Phantom, the Illinois Cyclone, Mercury’s Ghost. He could make even the most cynical scribe lose his head. Damon Runyon said Grange’s “left arm is a rod of steel. When he shoots it out straight at the on-rushing opposition they bowl over like so many tenpins… Everywhere in the melee of mud-smeared players the golden yellow top piece of Grange stood out like the helmet of Navarre.” John O’Hara made Red leaving a game sound like Achilles exiting the blood-soaked field before Troy. “Grange nodded and then began his jog trot to the dressing room. All alone, the slow trot down the seventy-five yards to the exit, and there wasn’t a man or woman not standing in the whole stadium. And if I was any judge, there was not a dry eye. There he was, the boy who had come through when the chips were really down, dragging his blanket behind him, and it was wonderful.”

Grantland Rice resorted to poetry:

A streak of fire, a breath of flame,

Eluding all who reach and clutch

A gray ghost thrown in the game

That rival hands may never touch;

A rubber bounding, blasting soul,

Whose destination is the goal—

Red Grange of Illinois.

After home games, Grange ducked into a movie theater near campus. His most peaceful moments were spent watching westerns. The theater was owned by C. C. Pyle. His initials were said to stand for “Cash and Carry.” Grange and Pyle represent archetypes: Grange was the first football star, Pyle the first sports agent.

Pyle read the newspapers and understood the troubles facing George Halas and his football team, the Chicago Bears, as well as the NFL itself. The league was new, the talent marginal, the games brutish, the audiences small. Without a star, the Bears would fold, as a half dozen charter members of the league—the Moline Tractors, the Dayton Triangles, the Rochester Jeffersons—already had. Pyle saw a need and an answer to that need. The Bears could not sell out Cubs Park, their home field, but Red Grange could.

One afternoon, Pyle sent for the athlete: Bring him to me. It was later said that Grange had been watching Harold Lloyd’s The Freshman. It seems too perfect, as The Freshman is a comic telling of Red’s own story: the kid from the sticks minted on the gridiron. Pyle was at his desk when Grange came in. “Charlie Pyle stood six-feet-one and weighed maybe 190 pounds,” Grange wrote. “He had been an excellent boxer, and could take care of himself. At the same time, he was a very dapper guy, a peacock strutting in spats and carrying a cane.”

Zuppke was furious when he heard the rumors about Pyle’s plans for Grange. The coach abhorred professional sports. He believed you played the game because you loved it. That made it wholesome. But getting paid to do what you love makes you a whore. The values of that era have been so thoroughly overturned it’s impossible to understand the horror professional sports stirred in college coaches. Zuppke believed Grange was in danger of losing his soul. But it was not just his playing style that made Grange modern: it was his attitude. When Zuppke questioned Grange’s motives, the player replied, “You get paid for coaching it. Why should it be wrong for me to get paid for playing it?”

Grange told Pyle to make the deal. Negotiations were conducted in secret. If the press found out, it could blacken Red’s name and diminish his value. Having recognized the potential of Grange, the notoriously cheap Halas—of whom Mike Ditka later said, “The old man throws around nickels like they’re manhole covers”—made the sort of deal he would never make again. Grange would join the Bears following his last college game, play the remainder of the season, then set off on a tour to exploit his fame. In return, Grange would get 50 percent of the gate, which he’d split with Pyle, who promised to augment the kid’s salary with commercials and endorsements. These arrangements would earn Grange over three hundred and fifty thousand dollars in two months; most players made a hundred bucks a week.

“I played my last game in Columbus against Ohio State,” Grange said later, much later. “It was kind of a madhouse because there were all these rumors that I was going to go pro right after it. I had to sneak out of the hotel. I went out the window and down the fire escape. I got a cab and crouched low as we sped to the station. I caught the train to Chicago, where I checked into the Belmont hotel under an assumed name. Charlie [Pyle] was already over at the Morrison Hotel, finishing up the deal with Halas.”

The Belmont was on the North Side, a beautiful brick tower composed of wings separated by a gilt lobby. It was the sort of place a man could change his name, take a nap, and vanish forever. Grange spent one night there, a long night and a lazy morning in an antechamber between existences. It’s the reason people follow athletes so assiduously, as if what happens to them really matters: they live a heightened version of our own lives, face the same dilemmas in all capitals. The passage from college to pro is another version of the passage from childhood to adulthood. In raging against the decision of his star, Coach Zuppke was, in his own way, trying to protect the innocence of youth. At some point, Red Grange would be too old to run for Illinois; a minute after that, he would be too old to run at all. Most of us face this privately, but Grange did it in public. For Grange, being an adult meant selling what he’d always done by instinct.

Early the next morning, Grange met Pyle and Halas at the Morrison. At thirty, George Halas was still boyish, slim, and jut-jawed, the college football star who’d co-founded the NFL. He still played, a wingback and defensive end who hit with glee. In Chicago, he would become a kind of god. Halas and his new star posed for photographers: shaking hands, grinning. Halas got down in a three-point stance. Grange pretended to fade back as Halas pretended to go deep.

When badgered by reporters who considered the signing a betrayal, Grange stayed calm. “I am going into professional football to make money out of it,” he said. “I have to get the money now, because people will forget about me in a few years.” When the Cubs Park box office opened the next day, the fans were lined up around the corner.

Grange returned to Champaign for the football team’s senior banquet. Zuppke did not want him there, but he showed up anyway. When the coach stood to speak, a moment normally reserved for platitudes, he glared at his star. “The Red Grange we know, and the Red Grange we’ve watched for three years, is a myth,” said Zuppke. “As time goes by those runs of his will grow in length with the telling. And soon they will be forgotten. I remember when I saw Heston, the great Heston, and thought there would never be another like him. Then I saw Pogue, the flashiest, shiftiest runner we ever had up to this time. I thought there would be no more like it. They all passed on. Grange will pass on. He will be forgotten. There is a saying that if a homely man comes into a room, sooner or later a homelier one will enter. And if a good-looking man comes in, some time there will be a better-looking one. Football, with its stars and individual stars, is like that.”

*

Grange played his first game as a Bear on Thanksgiving in 1925, five days after he went down the fire escape in Columbus. It was at Cubs Park, against the crosstown Cardinals. Pro football was derided in those days, especially when compared to the game played by the best colleges. Critics considered the NFL primitive, its ranks filled by has-beens, rejects. But the trouble Grange sometimes had in the pros showed just how good the NFL had become. In college, Grange had been playing against boys. In Chicago, he found himself facing men—bigger, heavier, meaner. There were clothesline tackles, head-slaps, secret violence in the piles. It was another part of the passage from campus to adult life: there was no sentimentality in the pros. If you dropped your head, you were going to pay. Grange ran for just thirty-six yards that first game, which ended in a scoreless tie. But for the first time in franchise history, the Chicago Bears sold out Cubs Park.

*

A few days later, the team set off on the barnstorming tour that saved the NFL, refilled its coffers, put its franchises on sound financial footing. A contemporary football player needs a week to recover after a game—a week to heal until he plays again. Before the Super Bowl, teams get two weeks. In the winter of 1925, Red Grange played nineteen games in sixty-seven days. He did this going both ways, playing offense and defense. He was pounded, punished, driven like a spike into the mud. It was a masochistic feat of endurance. He was spent like money, shot like ammunition. He would never be the same. You see it in the pictures: boyish and excited before, hollow-eyed and banged up after. Like so many that followed, he gave his body to pro football.

The Bears crossed the country by train, sleeping in their seats, their luggage overhead. Halas carried the footballs in a sack, checked the team in to hotels, thought up hooks for the local reporters. “Halas built the Bears,” Grange said. “When I joined them, he would lug the equipment around, write the press releases, sell the tickets, then run across the road and buy tape and help the trainer.”

The tour started on the East Coast, eight games in eleven days. Forty thousand people came to see Grange in Philadelphia, where the Bears “beat the Frankford Yellow Jackets in a heckuva rainstorm on a Saturday afternoon,” and “didn’t even have time to change out of those wet, muddy uniforms,” Joey Sternaman, a Bears quarterback, said. “We went right to the train, the last one to New York.” Seventy-seven thousand fans filled the Polo Grounds, the spillover crowding onto Coogan’s Bluff. Red intercepted a pass and ran thirty-four yards for a touchdown. It was the game that saved the New York Giants, who, before Grange sold all those tickets, were teetering on the edge of bankruptcy.

After the game, Babe Ruth stopped by the Astor Hotel in Times Square, where the Bears were staying. He wanted to meet the Galloping Ghost. The reporters following the tour—Runyon, Rice—loved it. Here was the athletic star of the age anointing the young prince. It was a benediction. The Babe offered Grange some counsel, words that were overheard, published, then added to the book of wisdom: “Kid, I’ll give you a bit of advice. Don’t believe anything they write about you. Get the dough while the getting’s good, but don’t break your heart trying to get it. And don’t pick up too many checks!”

William Brown McKinley, an Illinois congressman, watched the game in D.C., then took Halas and Grange to the White House to meet President Coolidge. The athletes stood in the Oval Office as McKinley made the introductions: “Mr. President, this is George Halas and Red Grange of the Chicago Bears.”

“Nice to meet you, young man,” said the president. “I’ve always liked animal acts.”

By the time the Bears reached Pittsburgh, they did not have enough healthy men to field a team. They played with ten. There was a reprieve, a day or two staring at hotel walls, before they went south. Atlanta, New Orleans, Jacksonville, Tampa, where Jim Thorpe was playing semi-pro for the Tigers. Seven games in fifteen days. From there, a long ride across Texas, shit-kicker towns forming and dissolving in the windows of the train, the cowboys in tall hats and boots lingering on the platforms. They played in Seattle, San Francisco, San Diego. In Portland, they played the Longshoremen, a team made up entirely of dockworkers. Grange was exhausted, but now and then he could still find that extra gear. “He had blinding speed, amazing lateral mobility, and exceptional change of pace and a powerful straight arm,” Heinz wrote. “He moved with high knee action but seemed to glide rather than run, and he was a master at using his blockers. What made him great, however, was his instinctive ability to size up a field and plot a run the way a great general can map not only a battle but a whole campaign.”

The tour ended in Los Angeles, where the Bears beat the L.A. Tigers seventeen to seven in the Coliseum as seventy-five thousand people watched, the largest crowd ever for a pro game. The team stayed in town for a few weeks. Douglas Fairbanks took Grange to the hot spots, introducing him to celebrities. He danced with Mary Pickford, got tanked at the Derby. In one picture, his face is wet with tears of laughter. In another, he sits in a chaise beside a hotel pool. “The boys bought camel hair coats and snap-brim hats,” Grange wrote. “They became a classy lot.”

Grange visited RKO Pictures, where he met the studio chairman, Joseph Kennedy. A handsome man, taller than Red, Kennedy was in the middle of his Hollywood interlude. “He spoke entirely about what wonderful athletes his sons were,” Grange wrote. “He said they were best at touch football. He was especially proud of Jack, five or six. He said he thought they all would do well in athletics.”

Kennedy put Grange in the pictures, producing a handful of quickie movies that cemented the athlete’s fame: The Galloping Ghost and A Racing Romeo and One Minute to Play. He was beat up when he got back to Chicago. He’d never be forgotten but he’d never be the same. He rescued the Bears and the NFL but destroyed his body. His consolations were money and acclaim, but he’d already begun to tire of them. “Being famous is bunk,” he said. “In fact, I’ve never felt worse. The newspapers have had me engaged to 18 girls I’ve never met. When you’re under the spotlight, you can’t tell a strange woman the way to the station without being mentioned in a divorce case.”

*

In recent years, sports analysts have questioned Red Grange’s greatness by citing his paltry statistics: five hundred and sixty-nine yards, twenty-one touchdowns. But Grange hardly played in the NFL. Soon after the Bears returned from the West Coast, Pyle got in a fight with Halas, a blowup that would take the Ghost away from Chicago just as his career was getting started.

As far as Pyle was concerned, the Bears survived only because of Grange. He did not want money in return—he wanted a piece of the franchise. Pyle understood a great truth of America: if you want to count, you’ve got to own. It was a red line for Halas: he would maintain control of his Bears. He refused, probably believing Grange, without options, would have to come back. What’s he going to do? Start his own team? But that’s exactly what Pyle did: with a hustler’s sense that New York was the only town that mattered, he put together the New York Football Yankees. But when Pyle applied for admission to the NFL, the Giants’ owner, Tim Mara, who did not want the competition, blocked him.

Pyle contacted promoters and moneymen in other towns and talked them into forming a rival league. The American Football Conference consisted of nine teams, including the Boston Bulldogs, the Brooklyn Horsemen, the Philadelphia Quakers, and the Cleveland Panthers. Grange’s Yankees did OK, but the rest foundered. The Boston Bulldogs folded after seven or eight games. Brooklyn lasted only four. The Quakers—the league champions—folded after the season, at which point everything collapsed. The NFL agreed to admit the Yankees, but, at Mara’s insistence, they were forced to play in Brooklyn.

Grange returned to Cubs Park—by then renamed Wrigley Field—to face the Bears in November 1927. When the game started, he was the same Grange he’d been in Chicago, Champaign, and Wheaton. By the end, he was a ruin. It happened late. The Bears were winning ten to zero. The outcome had been decided, but the fans chanted for Grange. He came out of the backfield, loped down the sideline, accelerated, getting clear of Bears defender George Trafton. He went up for the ball, caught it. But as he came down, his cleat stuck in the turf. Tafton was on him, bowling him over, but the cleat held fast. Red’s knee twisted. Something deep inside snapped. Red howled, rolling on the grass as the fans jumped to their feet. You could hear Grange curse from the bleachers. Teammates helped him up. As soon as his foot touched, his knee buckled.

An injury can define an era: Mickey Mantle ruining his knee on a drain at Yankee Stadium in his rookie year; Bo Jackson dislocating his hip on a meaningless play when he was twenty-nine: it makes fate seem like a joke. For fans, such moments assume the dimensions of a parable: you see it in triptych, as in an altarpiece. In the first panel, Red Grange is running upfield, still a boy; in the second, his cleat, seen in magnified detail, is planted in the turf as Trafton closes in like a demon; in the third, he is being carried away, arms dangling, eyes searching the sky. When asked about it later, Halas shook his head sadly and said, “It was a clean hit.”

Grange missed the rest of the 1927 season and all of 1928. He went to California, where he tried out for the movies. He got small parts in serials, ate, drank, put on weight. He starred in a feature about a football player who foils gamblers trying to fix a big game. He performed his own stunts, and it was while executing a big game sequence that he realized his knee had healed. He was not as fast as he’d been, could not move as he had, but he could get downfield. Halas was still interested in bringing the Ghost back to the Bears. He was still angry about Grange’s defection—Halas could hold a grudge—but got over it. Even if Red was only half of what he’d been, that would still make him better than everyone else.

Grange returned in 1929. He was twenty-six. You can see photos taken on the occasion. He suddenly looks much older. There are circles under his eyes, his face is filled with lines. From the first play, it was clear that he was not the same. He’d lost his ability to cut. If he tried to change direction, his knee failed. If he wanted to turn, he had to slow down, which meant no more broken-field rambles. He became a straight-ahead runner, like a modern fullback. He was not going to fool anyone, but if you needed three yards, he could get them.

This was Grange’s signature achievement: not how he had played when he possessed the greatest skills, but how he played when those skills were gone. He’s the template of the old pro, the natural who must find a way to compete after injury has taken his speed. In doing this, he forged a model for all us mortals who want to contribute even as we slouch toward the fourth quarter of life. An athlete with a long career will have distinct periods, in the way of a great painter. There was the young Picasso, who could draw anything, there was the blue-period Picasso, there was the Picasso of cubes, then there was the old Picasso, who worked furiously to find a more urgent and spontaneous approach to painting. In Grange, you saw it on defense: that’s where he made his late-career mark. He used all he’d learned while outsmarting tacklers to craft a new defensive style, to create a new position. He set up three yards off the line, where the linebacker is today. From there, he could look into the backfield and read the positions of the halfback and runners. He would shout to his teammates, telling them exactly what was coming—who would get the ball, how the play would develop. His lack of speed did not matter, as he was usually there when the ball arrived. He broke up plays, made interceptions, foiled even the speediest backs. He was like the once-master thief hired by the consortium to protect the banks.

Grange seemed like an ancient when he played his last game, in 1935, though he was just thirty-three. There’s a picture of him suiting up, pulling a jersey over his pads. He looks so weary. Perhaps no one has ever been older than Red Grange was that afternoon. If young Red racing in the lots of Wheaton was the beginning of football, this is the end. A man who would be young anywhere else is finished here. “Every player knows when his time is up,” Grange said. “When the game isn’t important anymore, and you don’t really like it that much—it’s time to get out.”

In the last minutes, the Bears had the ball on New York’s twenty, way ahead with little time left. Bears quarterback Dutch Brumbaugh took a knee in the huddle. He said, “Alright, listen up. I’m giving the ball to Red for the last time. Boys, let’s give him some help.”

“It was in a game against the Giants in Gilmore stadium in Hollywood in January of 1935,” Grange said later. “It was the last period, and we had a safe lead and I was sitting on the bench. George Halas said to me: ‘Would you like to go in, Red?’ I said, ‘No, thanks.’ Everybody knew this was my last year. He said: ‘Go ahead. Why don’t you run it just once more?’ So I went in and we lined up and they called a play for me. As soon as I got the ball and started to go I knew that they had framed it with the Giants to let me run. That line just opened and I went through and started down the field. The farther I ran, the heavier my legs got and the farther those goal posts seemed to move away. I was thinking: ‘When I make the end-zone, I’m going to take off these shoes and shoulder pads for the last time.’ With that, something hit me from behind and down I went on the ten-yard line. It was Cecil Irvin, a 230-pound tackle. He was so slow that, I guess, they never bothered to let him in on the plan. But when he caught me from behind, I really knew I was finished.”

*

Then Red went away from there. First to L.A., where he figured his stardom would guarantee a velvet age in pictures, but quickly discovered the short half-life of a sports celebrity. Once you’re off the field, they forget. New stars keep coming, the game keeps changing, and before you have reached middle age, you’re a relic. As he’d been the first modern running back and NFL star, Grange now became the model of that same man in retirement, a once-great player ruined for any sort of anonymous life. He returned to Chicago, a great city for many reasons, not least because people there do not forget. If you were Red Grange in Chicago, you always will be Red Grange in Chicago. He opened a restaurant called the 77 Club, named for his jersey number. Shades of Ditka’s on Chestnut. Shades of Walter Payton’s Roundhouse in Aurora. When I was a kid, The Red Grange Show was on the radio. The mediocre young players who filled the Bears roster in those years seemed to regard him as just another media hack who could not understand the game. He’d gone into a half dozen other fields by then: life insurance, car sales. On occasion, he worked as an after-dinner speaker. He seemed to represent football in its purest state. Asked why he played, he seemed confused by the question. “What do you mean why did I play? Why do you play anything? To win.”

He finished in the classic way, moving to Florida, wandering south like a bird, settling in a resort, Indian Lakes Estates, in the middle of the state, where, now and then, as his face filled out, as his body collapsed, he gave an interview for a remembrance or documentary. You run and slip the tackle before the multitudes, but you grow old alone. He developed Parkinson’s. The provinces of his body revolted. The Iceman wilted in the sun. He died in 1991. He was eighty-eight. He had played the game when he was young, several lifetimes ago, but that was all that would be remembered. It must have seemed like it had happened to a different person, in a previous incarnation. For a great player, there are a few years of action followed by decades of remembering. When he died, my first thought was, I can’t believe he was alive only yesterday! It was like learning that a field commander who’d won the day for Napoleon at Austerlitz was still living in Miami. I devoured every obituary, reminiscence, photo. Best were Red’s own words, quoted in one of those articles, explaining what the game had taught him. “To take a knock and give one,” he said, “to get kicked around a little and not get mad about it, and you learn to go out and give out just as you receive.”